Land Occupation in the Northern Province and Comments on Steps Required If the GOSL Is Genuine in Its Commitments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fit.* IRRIGATION and MULTI-PURPOSE DEVELOPMENT

fit.* The Historic Jaya Ganga — built by King Dbatustna in tbi <>tb century AD to carry the waters of the Kala Wewa to the ancient city tanks of Anuradbapura, 57 miles away, while feeding a number of village tanks in its course. This channel is also famous for the gentle gradient of 6 ins. per mile for the first I7 miles and an average of 1 //. per mile throughout its length. Both tbeKalawewa andtbefiya Garga were restored in 1885 — 18 8 8 by the British, but not to their fullest capacities. New under the Mabaweli Diversion project, the Kill Wewa his been augmented and the Jaya Gingi improved to carry 1000 cusecs of water. The history of our country dates back to the 6th century B.C. When the legendary Vijaya landed in L->nka, he is believed to have found an island occupied by certain tribes who had already developed a rudimentary sys tem of irrigation. Tradition has it that Kuveni was spinning cotton on the bund of a small lake which was presumably part of this ancient system. The development of an ancient civilization which was entirely depen dent on an irrigation system that grew in size and complexity through the years is described in our written history. Many examples are available which demonstrate this systematic development of water and land re sources throughout the so-called dry zone of our country over very long periods of time. The development of a water supply and irrigation system around the city of Anuradhapuia may be taken as an example. -

Floods and Affected Population

F l o o d s a n d A f f e c t e d P o p u l a t i o n Ja f f n a D i s t r i c t / N ov e m b e r - D e c e m b e r 2 0 0 8 J a f f n a Population Distribution by DS Division 2007 Legend Affected population reported by the Government Agent, Jaffna as at 30 November 2008 Area Detail Estimated Population in 2007 Legend 4,124 - 5,000 # of Affected Point Pedro Point Pedro Persons Sandilipay Tellipallai 5,001 - 1,0000 Sandilipay Tellipallai Karaveddy Karaveddy 500 - 1,0000 10,001 - 20,000 Kopay 10,001 - 20,000 Chankanai Uduvil Kopay 20,001 - 30,000 Karainagar Chankanai Uduvil Karainagar 20,001 - 30,000 30,001 - 50,000 30,001 - 40,000 Kayts 50,001 - 60,000 Kayts Kayts 40,001 - 50,000 Kayts Chavakachcheri 60,001 - 65,000 Kayts Chavakachcheri Kayts JaffnaNallur Jaffna Nallur Velanai 65,001 - 75,000 Velanai Velanai Maruthnkerny Velanai Maruthnkerny Velanai Velanai Velanai Velanai Note : Heavy rains that started on 22nd November 2008 have provoked floods in several districts of Sri Lanka, mainly Delft Delft Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, Mannar Ü and Trincomalee. Ü Kilometers Kilometers This map focuses on affected areas in 0 10 20 western Jaffna as data has been 0 10 20 made available on a regular basis. Relief support was provided to ASAR Image Classification as at 27 November 2008 Legend affected populations by both the Government of Sri Lanka and Hydro-Classification agencies. -

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula

Tropical Agricultural Research Vol. 23 (3): 237 – 248 (2012) Characterization of Irrigation Water Quality of Chunnakam Aquifer in Jaffna Peninsula A. Sutharsiny, S. Pathmarajah1*, M. Thushyanthy2 and V. Meththika3 Postgraduate Institute of Agriculture University of Peradeniya Sri Lanka ABSTRACT. Chunnakam aquifer is the main lime stone aquifer of Jaffna Peninsula. This study focused on characterization of Chunnakam aquifer for its suitability for irrigation. Groundwater samples were collected from wells to represent different uses such as domestic, domestic with home garden, public wells and farm wells during January to April 2011. Important chemical parameters, namely electrical conductivity (EC), chloride, calcium, magnesium, carbonate, bicarbonate, sulfate, sodium and potassium were determined in water samples from 44 wells. Sodium percentage, Sodium adsorption ratio (SAR), and residual Sodium Carbonate (RSC) levels were calculated using standard equations to map the spatial variation of irrigation water quality of the aquifer using GIS. Groundwater was classified based on Chadha diagram and US salinity diagram. Two major hydro chemical facies Ca-Mg-Cl-SO4 and Na-Cl-SO4 were identified using Chadha diagram. Accordingly, it indicates permanent hardness and salinity problems. Based on EC, 16 % of the monitored wells showed good quality and 16 % showed unsuitable water for irrigation. Based on sodium percentage, 7 % has excellent and 23 % has doubtful irrigation water quality. However, according to SAR and RSC values, most of the wells have water good for irrigation. US salinity hazard diagram showed, 16 % as medium salinity and low alkali hazard. These groundwater sources can be used to irrigate all types of soils with little danger of increasing exchangeable sodium in soil. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 7 Sri Lanka International Religious Freedom Report 2008 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor The Constitution accords Buddhism the "foremost place" and commits the Government to protecting it, but does not recognize it as the state religion. The Constitution also provides for the right of members of other religious groups to freely practice their religious beliefs. There was no change in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the period covered by this report. While the Government publicly endorses religious freedom, in practice, there were problems in some areas. There were sporadic attacks on Christian churches by Buddhist extremists and some societal tension due to ongoing allegations of forced conversions. There were also attacks on Muslims in the Eastern Province by progovernment Tamil militias; these appear to be due to ethnic and political tensions rather than the Muslim community's religious beliefs. The U.S. Government discusses religious freedom with the Government as part of its overall policy to promote human rights. U.S. Embassy officials conveyed U.S. Government concerns about church attacks to government leaders and urged them to arrest and prosecute the perpetrators. U.S. Embassy officials also expressed concern to the Government about the negative impact anticonversion laws could have on religious freedom. The U.S. Government continued to discuss general religious freedom concerns with religious leaders. Section I. Religious Demography The country has an area of 25,322 square miles and a population of 20.1 million. Approximately 70 percent of the population is Buddhist, 15 percent Hindu, 8 percent Christian, and 7 percent Muslim. -

The Government of the Democratic

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2019 DEPARTMENT OF STATE ACCOUNTS GENERAL TREASURY COLOMBO-01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. 1. Note to Readers 1 2. Statement of Responsibility 2 3. Statement of Financial Performance for the Year ended 31st December 2019 3 4. Statement of Financial Position as at 31st December 2019 4 5. Statement of Cash Flow for the Year ended 31st December 2019 5 6. Statement of Changes in Net Assets / Equity for the Year ended 31st December 2019 6 7. Current Year Actual vs Budget 7 8. Significant Accounting Policies 8-12 9. Time of Recording and Measurement for Presenting the Financial Statements of Republic 13-14 Notes 10. Note 1-10 - Notes to the Financial Statements 15-19 11. Note 11 - Foreign Borrowings 20-26 12. Note 12 - Foreign Grants 27-28 13. Note 13 - Domestic Non-Bank Borrowings 29 14. Note 14 - Domestic Debt Repayment 29 15. Note 15 - Recoveries from On-Lending 29 16. Note 16 - Statement of Non-Financial Assets 30-37 17. Note 17 - Advances to Public Officers 38 18. Note 18 - Advances to Government Departments 38 19. Note 19 - Membership Fees Paid 38 20. Note 20 - On-Lending 39-40 21. Note 21 (Note 21.1-21.5) - Capital Contribution/Shareholding in the Commercial Public Corporations/State Owned Companies/Plantation Companies/ Development Bank (8568/8548) 41-46 22. Note 22 - Rent and Work Advance Account 47-51 23. Note 23 - Consolidated Fund 52 24. Note 24 - Foreign Loan Revolving Funds 52 25. -

Northern Road Connectivity Project - Additional Financing

Resettlement Plan April 2014 Sri Lanka: Northern Road Connectivity Project - Additional Financing Prepared by the Road Development Authority, Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 23 April 2014) Currency unit - Sri Lankan rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0 .0076917160 $1.00 = SLR 130.010000 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank CBO - Community-based organization CSC - Construction supervision consultant DS - Divisional Secretary DSD - Divisional Secretariat Division EA - Executing Agency ESDD - Environment and Social Development Division GN - Grama Niladhari GND - Grama Niladhari Divisions GOSL - Government of Sri Lanka GRC - Grievance Redress Committee GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism IA - Implementing Agency IRP - income restoration program LAA - Land Acquisition Act LARS - land acquisition and resettlement survey MIS - management information systems MOHPS - Ministry of Highways, Ports and Shipping NIRP - National Involuntary Resettlement Policy NRCP - Northern Road Connectivity Project NRCP - AF - Northern Road Connectivity Project Additional Financing NP - Northern Province NGO - Nongovernment organization PD - Project Director PEA - Project Executing Agency PIU - Project Implementation Unit RDA - Road Development Authority REA - Rapid Environmental Assessment RHS - Right Hand Side ROW - Right-of-way SES - Socioeconomic survey SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TOR - Terms of reference NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

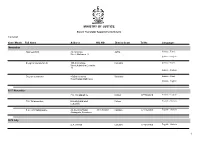

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Download the Conference Book

Colombo Conclave 2020 Colombo Conclave 2020 Published in December, 2020 © Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka ISBN 978-624-5534-00-5 Edited by Udesika Jayasekara, Ruwanthi Jayasekara All rights reserved. No portion of the contents maybe reproduced or reprinted, in any form, without the written permission of the Publisher. Opinions expressed in the articles published in the Colombo Conclave 2020 are those of the authors/editors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the INSSL. However, the responsibility for accuracy of the statements made therein rests with the authors. Published by Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka 8th Floor, ‘SUHURUPAYA’, Battarmulla, Sri Lanka. TEL: +94112879087, EMAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.insssl.lk Printed by BANDARA TRADINGINT (PVT) LTD No. 106, Main Road, Battaramulla, Sri Lanka TEL: +9411 22883867 / +94760341703, EMAIL: [email protected] CONTENTS CONCEPT PAPER 1 INAUGURAL SESSION Biography 5 Admiral (Prof.) Jayanath Colombage RSP, VSV, USP, rcds, psc MSc (DS), MA (IS), Dip in IR, Dip in CR, FNI (Lond) Director General, Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka and Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Welcome Remarks 6 Admiral (Prof.) Jayanath Colombage RSP, VSV, USP, rcds, psc MSc (DS), MA (IS), Dip in IR, Dip in CR, FNI (Lond) Director General, Institute of National Security Studies Sri Lanka and Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Biography 9 Maj Gen (Retd) Kamal Gunaratne WWV RWP RSP USP ndc psc MPhil Secretary, Ministry of Defence Keynote Address 10 Maj Gen (Retd) Kamal Gunaratne WWV RWP RSP USP ndc psc MPhil Secretary, Ministry of Defence SESSION 1 - REDEFINING THREATS TO NATIONAL SECURITY Biography 15 Amb.