Sophie Menter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophie Menter Zählte in Den Letzten Jahrzehnten Des 19

Menter, Sophie standensein nicht in Unzufriedenheit mündet.“ (César Cui in „Nedelja“ [„Die Woche“] vom 18. Februar 1884, zit. n. Vinocour 2006, S. 61) Profil Sophie Menter zählte in den letzten Jahrzehnten des 19. Jahrhunderts zu den großen Virtuosinnen und herausra- genden Liszt-Interpretinnen, die von London bis St. Pe- tersburg über 40 Jahre das Publikum zu Begeisterungs- stürmen hinriss. Sophie Menter wurde u. a. von Friedrich Niest in Mün- chen und Carl Tausig in Berlin ausgebildet und musizier- te häufig gemeinsam mit Franz Liszt an zwei Flügeln, der sie als Pianistin sehr schätzte. Ihre Interpretationen sei- ner Werke, darunter besonders das Klavierkonzert Es- Dur, wurden legendär. Entsprechend wurde Sophie Men- ter von Beginn ihrer Karriere an von konservativer Seite angegriffen, die ihr zu wenig musikalische Sensibilität und zu viel Kraft vorwarf. Während ihrer Zeit als Hofpianistin am Hof von Löwen- berg lernte sie den Cellisten David Popper kennen, den Die Pianistin Sophie Menter. Fotografie Wegner & Mottu, sie 1872 heiratete und mit dem sie nach ihrer Ernennung Amsterdam und Utrecht, o.D. zur k.k. Hofpianistin 1877 vermutlich nach Pest zog. Von 1884 bis 1887 war Sophie Menter Professorin am Konser- Sophie Menter vatorium in St. Petersburg, wo sie die Klavierklasse von Ehename: Sophie Menter-Popper Louis Brassin übernahm, zu deren Schüler u. a. Vasilij Sa- pellnikoff und Vasilij Safnov gehörten. Nach ihrer Rück- * 17. Juli 1846 in München, Deutschland kehr aus St. Petersburg und der Scheidung von David † 23. Februar 1918 in Stockdorf bei München, Popper 1886 ließ sie sich auf Schloss Itter bei Kitzbühel Deutschland in Tirol nieder und unternahm von dort aus ihre Konzert- reisen nach Russland und England. -

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Mu

The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music 1988 December The Development of the Russian Piano Concerto in the Nineteenth Century Jeremy Paul Norris The Russian piano concerto could not have had more inauspicious beginnings. Unlike the symphonic poem (and, indirectly, the symphony) - genres for which Glinka, the so-called 'Father of Russian Music', provided an invaluable model: 'Well? It's all in "Kamarinskaya", just as the whole oak is in the acorn' to quote Tchaikovsky - the Russian piano concerto had no such indigenous prototype. All that existed to inspire would-be concerto composers were a handful of inferior pot- pourris and variations for piano and orchestra and a negligible concerto by Villoing dating from the 1830s. Rubinstein's five con- certos certainly offered something more substantial, as Tchaikovsky acknowledged in his First Concerto, but by this time the century was approaching its final quarter. This absence of a prototype is reflected in all aspects of Russian concerto composition. Most Russian concertos lean perceptibly on the stylistic features of Western European composers and several can be justly accused of plagiarism. Furthermore, Russian composers faced formidable problems concerning the structural organization of their concertos, a factor which contributed to the inability of several, including Balakirev and Taneyev, to complete their works. Even Tchaikovsky encountered difficulties which he was not always able to overcome. The most successful Russian piano concertos of the nineteenth century, Tchaikovsky's No.1 in B flat minor, Rimsky-Korsakov's Concerto in C sharp minor and Balakirev's Concerto in E flat, returned ii to indigenous sources of inspiration: Russian folk song and Russian orthodox chant. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 26,1906-1907, Trip

CARNEGIE HALL - NEW YORK Twenty-first Season in New York Sustrnt i^gmpijmttj ©nostra DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor Programme of % SECOND CONCERT THURSDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 6 AT 8.15 PRECISELY AND THE SECOND MATINEE SATURDAY AFTERNOON, DECEMBER 8 AT 2.30 PRECISELY WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER OSSIP GABRILOWITSGH the Russian will play in America this season with the Principal Orchestras, the Kneisel Quartet, the Boston Symphony Quartet, Leading Musical Organizations throughout the country, and in Recital CABRILOWITSCH will play only the PIANO Mmm$c%mlmw. 139 Fifth Avenue, New York For particulars, terms, and dates of Gabrilowitsch, address HENRY L. MASON 492 BoylBton Street, Boston 2 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1906-1907 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Willy Hess, Concertmeister. and the Members of the Orchestra in alphabetical order. Adamowski, J. Hampe, C. Moldauer, A. Adamowski, T. Heberlein, H. Mullaly, J. Akeroyd, J. Heindl, A. Miiller, F. Heindl, H. Bak, A. Helleberg, J. Nagel, R. Bareither, G. Hess, M. Nast, L. Barleben, C. Hoffmann, J. Barth, C. Hoyer, H. Phair, J. Berger, H. Bower, H. Keller, J. Regestein, E. Brenton, H. Keller, K. Rettberg, A. Brooke, A. Kenfield, L. Rissland, K. Burkhardt, H. Kloepfel, L. Roth, O. Butler, H. Kluge, M. Kolster, A. Sadoni, P. Debuchy, A. Krafft, W. Sauer, G. Dworak, J. Krauss, H. Sauerquell, J. Kuntz, A. Sautet, A. Eichheim, H. Kuntz, D. Schuchmann, F. Eichler, Kunze, M. Schuecker, H. i J. 1 Elkind, S. Kurth, R. Schumann, C. Schurig, R. Ferir, E. Lenom, C. -

David POPPER

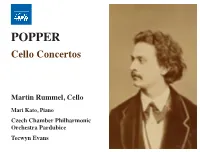

POPPER Cello Concertos Martin Rummel, Cello Mari Kato, Piano Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra Pardubice Tecwyn Evans David Popper (1843–1913) Cello Concertos The cellist David Popper was born in Prague in 1843, the element in the repertoire of aspirant cellists, while his and recorded here with piano accompaniment, a medium followed by the inevitable dotted rhythms of the rapid final son of the Prague Cantor. He studied the cello there other works include compositions that give an opportunity to which it is well suited. It is introduced by the piano, with movement, recalling elements of the opening. Suggesting under the Hamburg cellist Julius Goltermann, who had for virtuoso display. dotted rhythms that have a continuing part to play in the chamber music rather than a concerto, the work adds to taken up an appointment at the Prague Conservatory in Popper’s Cello Concerto No. 1 in D minor, Op. 8, whole work. The cello enters with a display of double- the series of four concertos that reflect Popper’s growing 1850. It was through Liszt’s then son-in-law, the pianist was published in Mainz in 1871 and dedicated to his stopping and is later to introduce a secondary lyrical maturity as a composer, with music rather than technical and conductor Hans von Bülow, that Popper was former teacher, Julius Goltermann. After two bars of theme. The following short Lento assai , starts in a sombre virtuosity at the heart of the final concerto. recommended in 1863 to a position as Chamber Virtuoso orchestral introduction, the soloist enters with an F major F minor, gradually assuming a more lyrical mood, as it at the court of the Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Konstantin ascending arpeggio, an indication of some harmonic leads, through a short cadenza, to a third movement, Keith Anderson von Hohenzollern, who had had a new residence with a ambiguity. -

The a Lis Auth Szt P Hen Pian Ntic No T Cho Trad Opin Diti N an on Nd

THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 1 2 THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION 3 4 THE AUTHENTIC CHOPIN AND LISZT PIANO TRADITION GERARD CARTER BEc LL B (Sydney) A Mus A (Piano Performing) WENSLEYDALE PRESS 5 Published in 2008 by Wensleydale Press ABN 30 628 090 446 165/137 Victoria Street, Ashfield NSW 2131 Tel +61 2 9799 4226 Email [email protected] Designed and printed in Australia by Wensleydale Press, Ashfield Copyright © Gerard Carter 2008 All rights reserved. This book is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (for example, a fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism or review) no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. ISBN 978-0-9805441-2-1 This publication is sold and distributed on the understanding that the publisher and the author cannot guarantee that the contents of this publication are accurate, reliable, complete or up to date; they do not take responsibility for any loss or damage that happens as a result of using or relying on the contents of this publication and they are not giving advice in this publication. 6 7 8 CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction ... 11 Chapter 2: Chopin and Liszt as composers ...19 Chapter 3: Chopin and Liszt as pianists and teachers ... 29 Chapter 4: Chopin tradition through Mikuli ... 55 Chapter 5: Liszt tradition through Stavenhagen and Kellermann .. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 26,1906-1907, Trip

INFANTRY HALL . PROVIDENCE Twenty-sixth Season, J906-J907 DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor fljrmjramm? nf % Third and Last Concert WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE THURSDAY EVENING, MARCH 7 AT 8.15 PRECISELY PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 1 \ OSSIP WITSGH the Russian Pianist will play in America this season with the Principal Orchestras, the Kneisel Quartet, the Boston Symphony Quartet, Leading Musical Organizations throughout the country, and in Recital CABRILOWITSCH will play only the PIANO Conrad Building, Westminster Street For particulars, terms, and dates of Gabrilowitsch, address HENRY L. MASON 492 Boylston Street, Boston 1 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1906-1907 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Willy Hess, Concertmeister, and the Members of the Orchestra in alphabetical order. Adamowski, J. Hampe, C. Moldauer, A. Adamowski, T. Heberlein, H. Mullaly, J. Akeroyd, J. Heindl, A. Muller, F. Heindl, H. Bak, A. Helleberg, J. Nagel, R. Bareither, G. Hess, M. Nast, L. Barleben, C. Hoffmann, J. Barth, C. Hoyer, H. Phair, J. Berger, H. Bower, H. Keller, J. Regestein, E. Brenton, H. Keller, K. Rettberg, A. Brooke, A. Kenfield, L. Rissland, K. Burkhardt, H. Kloepfel, L. Roth, O. Butler, H. Kluge, M. Kolster, A. Sadoni, P. Currier, F. Krafft, W. Sauer, G. Debuchy, A. Krauss, H. Sauerquell, J. Kuntz, A. Sautet, A. Dworak, J. Kuntz, D. Schuchmann, F. Eichheim, H. Kunze, M. Schuecker, H. Eichler, J. Kurth, R. Schumann, C. Elkind, S. Schurig, R. Lenom, C. Senia, T. Ferir, E. Loeffler, E. Seydel, T. Fiedler, B. Longy, G. Sokoloff, N. Fiedler, E. Lorbeer, H. Strube, G. -

I Would Like Something Very Poetic and at the Same Time Very Simple, Intimate and Human!"

"I would like something very poetic and at the same time very simple, intimate and human!" Previously unknown or unidentified letters by Tchaikovsky to correspondents from Russia, Austria and France (Tchaikovsky Research Bulletin No. 2) Presented by Luis Sundkvist Contents Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 List of abbreviations .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 I. Russia (Nicolas de Benardaky, Pavel Peterssen, Robert von Thal) .. .. 6 II. Austria (unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 16 III. France (Léonce Détroyat, Paul Dultier, Louis de Fourcaud, Martin Kleeberg, Ambroise Thomas, Pauline Viardot-García) .. 19 New information on previously identified letters .. .. .. .. .. 51 Chronological list of the 17 letters by Tchaikovsky presented in this bulletin .. 53 Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. 55 Introduction1 One of the most surprising letters by Tchaikovsky featured in the first Research Bulletin was that which he wrote in the summer of 1892 to the French librettist Louis Gallet, asking him to resume work on the libretto for the opera La Courtisane.2 For in the standard reference books on Tchaikovsky it had always been assumed that after 1891 he had no longer expressed any interest in the projected French-language opera in three acts, La Courtisane, or Sadia, that, back in 1888, he had agreed to write in collaboration with Gallet and his fellow-librettist Léonce Détroyat.3 This letter suggested otherwise, and whilst it is still true that Tchaikovsky does not seem to have even made any musical sketches for this opera -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

NEW NATIONAL THEATRE, WASHINGTON Twenty-sixth Season, J90^-J907 DR. KARL MUCK, Conductor programme of % Fifth and Last Matinee WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIP- TIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY AFTERNOON, MARCH 19 AT 4.30 PRECISELY PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS, MANAGER 08SIP GABRILOWITSCH the Russian Pianist will play in America this season with the Principal Orchestras, the Kneisel Quartet, the Boston Symphony Quartet, Leading Musical Organizations throughout the country, and in Recital GABRILOWITSCH will play only the ifaun&ife PIANO ifejm&ifaittlhtdk Boston New York For particulars, terms, and dates of Gabrilowitsch, address HENRY L. MASON 492 Boylston Street, Boston 2 Boston Symphony Orchestra PERSONNEL TWENTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1906-1907 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor Willy Hess, ConcertmeisUr> and the Members of the Orchestra in alphabetical order. Adamowski, J. Hampe, C. Moldauer, A. Adamowski, T. Heberlein, H. Mullaly, J. Akeroyd, J. Heindl, A. Muller, F. Heindl, H. Bak, A. Helleberg, J. Nagel, R. Bareither, G. Hess, M. Nast, L. Barleben, C. Hoffmann, J. Barth, C. Hoyer, H. Phair, J. Berger, H. Bower, H. Keller, J. Regestein, E» Brenton, H. Keller, K. Rettberg, A. Brooke, A. Kenfield, L. Rissland, K. Burkhardt, H. Kloepfel, L. Roth, O. Butler, H. Kluge, M. Kolster, A. Sadoni, P. Currier, F. Krafft, W. Sauer, G. Debuchy, A. Krauss, H. Sauerquell, J. Kuntz, A. Sautet, A. Dworak, J. Kuntz, D. Schuchmann, F. Eichheim, H. Kunze, M. Schuecker, H. Eichler, J. Kurth, R. Schumann, C. Elkind, S. Schurig, R. Lenom, C. Senia, T. Ferir E. Loeffler, E. Seydel, T. Fiedler, B. Longy, G. Sokoloff, N. Fiedler, E. Lorbeer, H. -

Tchaikovsky Research Bulletin No. 1

"Klin, near Moscow, was the home of one of the busiest of men…" Previously unknown or unidentified letters by Tchaikovsky to correspondents from Russia, Europe and the USA Presented by Luis Sundkvist and Brett Langston Contents Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 I. Russia (Milii Balakirev, Adolph Brodsky, Mariia Klimentova-Muromtseva, Ekaterina Laroche, Iurii Messer, Vasilii Sapel'nikov) .. .. .. 5 II. Austria (Anton Door, Albert Gutmann) .. .. .. .. .. 15 III. Belgium (Désirée Artôt-Padilla, Joseph Dupont, Jean-Théodore Radoux, Józef Wieniawski) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 IV. Czech Republic (Adolf Čech, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. 25 V. France (Édouard Colonne, Eugénie Vergin Colonne, Louis Diémer, Louis Gallet, Lucien Guitry, Jules Massenet, Pauline Viardot-García, three unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 VI. Germany (Robert Bignell, Hugo Bock, Hans von Bülow, Paul Cossmann, Mathilde Cossmann, Aline Friede, Julius Laube, Sophie Menter, Selma Rahter, Friedrich Sieger, two unidentified) .. .. .. .. 55 VII. Great Britain (George Bainton, George Henschel, Francis Arthur Jones, Ethel Smyth, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 69 VIII. Poland (Édouard Bergson, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. 85 IX. United States (E. Elias, W.S.B. Mathews, Marie Reno) .. .. .. 89 New locations for previously published letters .. .. .. .. .. 95 Chronological list of the 55 letters by Tchaikovsky presented in this article .. 96 Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. 101 Introduction Apart from their authorship, the only thing that most of the -

Also with Wendy Warner on Cedille Records

Also with Wendy Warner on Cedille Records “One runs out of superlatives for “[Pine and Warner] possess both a CD such as this. It is a joy to power and warmth. Their hear [these pieces] played with such collaboration already represents a compelling mixture of discipline, musicianship of mature insight, intelligence and excitement. [Pine] hair-raising electricity, and intense and Warner[‘s] . electric playing involvement. Unhesitatingly puts this CD in a class of its own.” recommended.” – International Record Review – Fanfare To my teachers Kalman and Nell Novak Wendy Warner Plays Popper & Piatigorsky — Wendy Warner Producer: Judith Sherman David Popper (1843–1913) Gregor Piatigorsky (1903–1976) Engineer: Bill Maylone Suite for Cello and Piano, Variations on a Paganini Theme (1946) (16:07)* Op. 69 (27:30) Session Director: James Ginsburg bo Theme (0:29) Recorded August 27–31, 2007 (Popper Op. 11 and Op. 69) and June 26–27, 2008 1 I. Allegro giojoso (10:37) bp Variation 1 (Pablo Casals) (1:09) (Popper Op. 50 and Piatigorsky) in the Fay and Daniel Levin Performance Studio, 2 II. Tempo di Menuetto (6:07) bq WFMT, Chicago Variation 2 (Paul Hindemith) (0:46) 3 III. Ballade (4:47) br Variation 3 (Raya Garbousova) (0:32) Cellos: Joseph Gagliano, 1772 (Popper Op. 11 and Op. 69); Carl Becker, 1963 (Popper Op. 50 and Piatigorsky) 4 IV. Finale (5:50) bs Variation 4 (Erica Morini) (0:46) bt Steinway Piano Piano Technician: Charles Terr Three Pieces, Op. 11 (12:31) Variation 5 (Felix Salmond) (1:05) cu Variation 6 (Joseph Szigeti) (1:26) Art Direction: Adam Fleishman / www.adamfleishman.com 5 Widmung (5:59) cl Variation 7 (Yehudi Menuhin) (0:52) Front Cover Photo by Oomphotography / www.oomphotography.com 6 Humoreske (2:42) cm Variation 8 (Nathan Milstein) (0:35) 7 Mazurka (3:44) Cedille Records is a trademark of The Chicago Classical Recording Foundation, a not-for-profit cn Variation 9 (Fritz Kreisler) (1:20) foundation devoted to promoting the finest musicians and ensembles in the Chicago area. -

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: the Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility

Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos: The Catalogues, Technologies, Archiving and Accessibility Peter Phillips A Thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Historical Performance Unit Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2016 i Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Declaration I declare that the research presented in this thesis is my own original work and that it contains no material previously published or written by another person. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted to any other institution for the award of a higher degree. All illustrations, graphs, drawings and photographs are by the author, unless otherwise cited. Signed: _______________________ Date: 2___________nd July 2017 Peter Phillips © Peter Phillips 2017 Permanent email address: [email protected] ii Peter Phillips – Piano Rolls and Contemporary Player Pianos Acknowledgements A pivotal person in this research project was Professor Neal Peres Da Costa, who encouraged me to undertake a doctorate, and as my main supervisor, provided considerable and insightful guidance while ensuring I presented this thesis in my own way. Professor Anna Reid, my other supervisor, also gave me significant help and support, sometimes just when I absolutely needed it. The guidance from both my supervisors has been invaluable, and I sincerely thank them. One of the greatest pleasures during the course of this research project has been the number of generous people who have provided indispensable help. From a musical point of view, my colleague Glenn Amer spent countless hours helping me record piano rolls, sharing his incredible knowledge and musical skills that often threw new light on a particular work or pianist. -

Effective Practice Methods for David Popper's Virtuosic Pieces and the Realtionship Between Selected Pieces and Etudes So Youn Park

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Effective Practice Methods for David Popper's Virtuosic Pieces and the Realtionship Between Selected Pieces and Etudes So Youn Park Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC EFFECTIVE PRACTICE METHODS FOR DAVID POPPER’S VIRTUOSIC PIECES AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SELECTED PIECES AND ETUDES By SO YOUN PARK A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 Copyright © 2007 So Youn Park All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the treatise of So Youn Park defended on March 27, 2007. _________________________ Gregory Sauer Professor Directing Treatise _________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee Member _________________________ Melanie Punter Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii Dedicated to My parents and my husband, Do Young iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am truly grateful to many people who have helped me to successfully complete this treatise. First of all, I would like to express my great appreciation to my committee members: Professor Gregory Sauer, Professor Melanie Punter, and Dr. Evan Jones, for giving me their knowledge, time and effort. Most of all, I would like to thank my treatise director, Professor Sauer, for his insightful advice and ideas and his constant encouragement through this process. I am also deeply grateful to Professor Punter who always provided me her valuable advice and direction to help me finish my doctoral degree.