The Human Machine Art Interface: Arcade Port Aesthetics and Production Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homemade Arcade Cabinet by Crusso on September 23, 2010

Home Sign Up! Browse Community Submit All Art Craft Food Games Green Home Kids Life Music Offbeat Outdoors Pets Photo Ride Science Tech Homemade Arcade Cabinet by crusso on September 23, 2010 Table of Contents Homemade Arcade Cabinet . 1 Intro: Homemade Arcade Cabinet . 2 Step 1: Cabinet construction . 2 Step 2: Control panel . 6 Step 3: Keyboard drawer . 7 Step 4: Keyboard hack . 9 Step 5: Speakers . 12 Step 6: Video . 12 Step 7: Painting . 15 Step 8: Bezel . 19 Step 9: Backlight . 21 Step 10: Marquee . 23 Step 11: Coin door . 24 Step 12: Computer . 25 Step 13: Frontend . 26 Step 14: Artwork . 27 Related Instructables . 27 Comments . 28 http://www.instructables.com/id/Homemade-Arcade-Cabinet/ Intro: Homemade Arcade Cabinet Welcome! this is my first attempt to create a MAME arcade cabinet from scratch. I built this thing some years ago and just decided to upload it to instructables.com I tried to take as many pictures I could to show the step-by-step creation process. This project has many interesting topics in which I worked: woodworking, design, electronics, painting, programming. If you like this project please comment! Step 1: Cabinet construction I think a good blueprint is a must as a good starting point for this project. I wish I could created a 3d design but I only know a little bit about 3d tools. If you take this approach a good -and free- software to play with is Sketchup from Google. I chose the way of hand drawing designs. Since I wanted to build an old-fashioned cabinet I looked up to the Taito cabinets designs (Alpine Ski or Jungle King for example) Since I couldn't find any full sized blueprint of the cabinet I liked to build, I had to create it by my own. -

ACPI (Ang. Advanced Configuration and Power Interface, Zaawansowany Interfejs Zarządzania Konfiguracją I Energią) – Otwarty

ACPI (ang. Advanced Configuration and Power Interface, zaawansowany interfejs zarządzania konfiguracją i energią) – otwarty standard opracowany przez firmy Intel, Microsoft i Toshiba, do których później dołączyły HP oraz Phoenix, po raz pierwszy ogłoszony w grudniu 1996. ACPI zwiększa możliwości systemów zarządzania energią oferowane przez wcześniejsze rozwiązanie APM. Umożliwia systemowi operacyjnemu kontrolowanie ilości energii dostarczanej do poszczególnych urządzeń komputera (napędu CD-ROM, twardego dysku oraz urządzeń peryferyjnych) i, podobnie jak APM, umożliwia ich wyłączanie, gdy nie są używane a konieczne jest oszczędzanie energii. ADC - Przetwornik analogowo-cyfrowy A/C (ang. A/D – analog to digital; ADC – analog to digital converter), to układ służący do zamiany sygnału analogowego (ciągłego) na reprezentację cyfrową (sygnał cyfrowy). Dzięki temu możliwe jest przetwarzanie ich w urządzeniach elektronicznych opartych o architekturę zero-jedynkową oraz gromadzenie na dostosowanych do tej architektury nośnikach danych. Proces ten polega na uproszczeniu sygnału analogowego do postaci skwantowanej (dyskretnej), czyli zastąpieniu wartości zmieniających się płynnie do wartości zmieniających się skokowo w odpowiedniej skali (dokładności) odwzorowania. Przetwarzanie A/C tworzą 3 etapy: próbkowanie, kwantyzacja i kodowanie. Działanie przeciwne do wyżej wymienionego wykonuje przetwornik cyfrowo-analogowy C/A. AGP - Accelerated Graphics Port (AGP, czasem nazywany Advanced Graphics Port) – zmodyfikowana magistrala PCI opracowanej przez firmę Intel zaprojektowana do obsługi kart graficznych. Jest to 32- bitowa magistrala PCI zoptymalizowana do szybkiego przesyłania dużych ilości danych pomiędzy pamięcią operacyjną a kartą graficzną. Wyparta przez szybszą magistralę PCI Express. AGP Pro - specjalna wersja gniazda rozszerzeń AGP przeznaczona do profesjonalnych kart graficznych, które zużywają dużo prądu. Gniazdo AGP Pro ma 48 pinów więcej niż standardowe gniazdo AGP. Służą one niemal wyłącznie jako dodatkowe linie zasilania. -

Adding a 5 Pin DIN to an Amstrad CPC 464

arduitape.blogspot.com Adding a 5 pin DIN to an Amstrad CPC 464 Share 4-5 minutes Adding a 5 pin DIN to an Amstrad CPC 464 After mentioning that I had gotten a CPC and attached a DIN to it so that I could connect it to the TZXDuino I have had a few requests on how to do it so I thought I'd try a guide. You will need to purchase 180 degree 5 pin female din that is chassis mountable. This is the type that I purchased except mine also had a mounting plate too. The standard 6128 cassette connector is wired like this. Each pin is numbered on the back so that you know which one you are connecting it too so don't worry if the pins are in different positions as it depends on whether you are looking from the connection side or the soldering side. I would use different coloured wiring for each type of connection. I used the following Ground - Black Data Input - White Data Output - Pink Remote Control - Brown At this point I added 4 male pins to the end of my wiring so that I could build a connector so that I could easily disconnect the DIN should I need to work on the cassette drive. Next is connecting the wiring to the cassette drive Make sure that when you solder you do not create any shorts and connect the wiring as follows. Close Up your computer and then test to make sure that it all works. If you want to use the built in cassette recorder you just unplug the cassette leads from the DIN and use it as normal. -

The-Magpi-104-En-202104.Pdf

BUY IN PRINT WORLDWIDE MAGPI.CC/STORE Issue 104 April 2021 magpi.cc The official Raspberry Pi magazine HOME OF THE FUTURE Automate your home with Raspberry Pi Upcycle iPod Classic with Spotify Build an arcade magpi.cc/store machine 48 PAGES OF PROJECTS & TUTORIALS 210212_M2M_MAGPI_UK.indd 1 2/10/21 11:46 AM WELCOME WELCOME to The MagPi 104 elcome to the future. 2021 is a sci-fi year and science promised us hoverboards, jet packs, and robot butlers. We can’t do much about the first two (although we’re Wkeeping an eye out). But help around the home is definitely our domain. In this issue we asked resident home automation expert PJ Evans to design our home of the future with Raspberry Pi (page 34). The result is a fabulous collection of widgets, projects, and gizmos to Lucy Hattersley help around the house. I’ve already talked Rosie into installing some EDITOR Lucy is editor of The NeoPixel steps at home. MagPi magazine and continues to bash Meanwhile Rob has been looking how to take a Raspberry Pi her south London project and turn it into a Pico project (page 72). KG has started to home into shape. @LucyHattersley build an arcade machine (page 42). Nicola has been looking at an autonomous home robot (page 20). Me? I’ve been playing around with ARM assembly like the nerd I am (page 84). This issue has been a huge amount of fun! And we particularly like the illustration adorning this month’s cover. Thanks to Sam Alder GET A for incredible drawing skills (and Sam Ribbits for laying it out). -

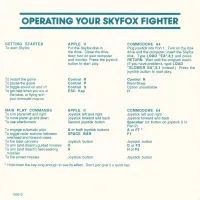

Skyfox Fighter

OPERATING YOUR SKYFOX FIGHTER GETTING STARTED APPLE II COMMODORE 64 To start Skyfox Put the Skyfox disk in Plug joystick into Port 1. Turn on the disk the drive. Close the drive drive and the computer; insert the Skyfox door; turn on your computer disk. Type LOAD "EA",8,1 and press and monitor. Press the joystick RETURN. Wait until the program loads. button to start play. (If you have problems, type LOAD "SLOWER EA",8,1 instead.) Press the joystick button to start play. To restart the game Control R Control R To pause the game Control P Run/Stop To toggle sound on and off Control S Option unavailable To get help when you are at ESC Key H the base, or flying with your computer map up MAIN PLAY COMMANDS APPLE II COMMODORE 64 To turn plane left and right Joystick left and right Joystick left and right To move plane up and down Joystick forward and back Joystick forward and back To use afterburners Second joystick button Spacebar (or button on joystick 2 in Port 2) To engage automatic pilot A or both joystick buttons AorF7* To toggle radar scanner between SPACE BAR F1 overhead and forward views To fire laser cannons Joystick button Joystick button To arm (and disarm) guided missiles G G or F3 To arm (and disarm) heat-seeking H H or F5 missiles To fire armed missiles Joystick button Joystick button • Hold down the key long enough to see' its effect. Don't just give it a quick tap. 103619 GETTING STARTED ATARI ST COMMODORE AMIGA To start Skyfox Put the Skyfox disk in After kickstarting your Amiga, insert the the drive and turn on the Skyfox disk in the drive. -

Commodore 64 Users Guide

INTRODUCTION Now that you've become more intimately involved with your Commo- dore 64, we want you to know that our customer support does not stop here. You may not know it, but Commodore has been in business for over 23 years. In the 1970's we introduced the first self-contained per- sonal computer (the PET). We have since become the leading computer company in many countries of the world. Our ability to design and manufacture our own computer chips allows us to bring you new and better personal computers at prices way below what you'd expect for this level of technical excellence. Commodore is committed to supporting not only you, the end user, but also the dealer you bought your computer from, magazines which publish how-to articles showing you new applications or techniques, and . importantly . software developers who produce programs on cartridge, disk and tape for use with your computer. We encourage you to establish or join a Commodore "user club" where you can learn new techniques, exchange ideas and share discoveries. We publish two separate magazines which contain programming tips, information on new products and ideas for computer applications. (See Appendix N). In North America, Commodore provides a "Commodore Information Network" on the CompuServe Information Service . to access this network, all you need is your Commodore 64 computer and our low cost VICMODEMtelephone interface cartridge (or other compatible modem). The following APPENDICEScontain charts, tables, and other informa- tion which help you program your Commodore 64 faster and more efficiently. They also include important information on the wide variety of Commodore products you may be interested in, and a bibliography listing of over 20 books and magazines which can help you develop your programming skills and keep you current on the latest information con- cerning your computer and peripherals. -

M the Official Amstrad Business Magazine

Vol. 1 No. 4 December 1986 AMSTRAD£1.25 | COMPUTING- V; ■ I mm m >■ V aL- The Official Amstrad Business Magazine The Condor 1 Commands - They couldn’t be simpler! Database Creation and Maintenance DEFINE Create, redefine or describe a database DESTROY Eliminate a database or file FORMAT Create or revise a form or HELP screen REORG Reorganize the structure of a database; add or delete items Information Input and Update APPEND Attach records of one database to another EMPTY Eliminate all data in a database ENTER Insert new data into a database POST Update entries in one database with those from another UPDATE Change entries in a J--.abase meeting specified cni Jiiitions Informations* ssingand Report Writing COMPARE ' ;v*i.*are orgies in two ■■■...•.vjfcsfa- /not) n • hing o editions and The Database Manager and Reporter. c. < RE ;• i JLT database COMPUTE . ie<: iesina You know that Caxton only publish superior software products. LIST 0; datf.'i j;,se records in Cardbox is the world’s best-selling simple electronic card index. sesjc :?-^er Brainstorm is the world’s first ideas processor. Scratchpad plus is the PRINT Pirfctf. shtab^va records in ewisr only enhanced Virtual Memory Spreadsheet available foryour PRINTER Pri; ;lei output control and Amstrad. And Touch ’n’ Go is the UK’s most highly respected disk- refection SELECT Select database records based typing T\itor. meeting specified conditions, creating a Now we present Condor 1 - Mainframe computing for your Amstrad. RESULT database SORT Sort database records by Condor 1 is an extensive database management and reporting system entries STAX View or print statistics of for the non-programmer. -

MIDI に関する技術系統化調査 1 Systematized Survey of MIDI and Related Technologies

MIDI に関する技術系統化調査 1 Systematized Survey of MIDI and Related Technologies 井土 秀樹 Hideki Izuchi ■ 要旨 MIDI(Musical Instrument Digital Interface)は、日本の MIDI 規格協議会(現 AMEI:一般社団法人 音楽電子事業協会)と国際団体の MMA(MIDI Manufacturers Association)により制定された電子楽器の 演奏データを機器間でデジタル転送するための共通規格である。 1981 年 6 月シカゴで開催された NAMM ショーで、共通インターフェースの可能性に関して、最初の呼 びかけを行ったのがローランド創業者の梯郁太郎である。この呼びかけに応じ、最初の規格案を提案したのが Dave Smith(Sequential Circuits Inc. 社長)であった。両者は MIDI の制定に尽力し、MIDI 規格がその後 の音楽産業の発展に貢献したことが評価され、MIDI 制定から 30 周年を迎える 2013 年第 55 回グラミー賞 にて、連名でテクニカル・グラミー・アワードを受賞している。 MIDI を使って、異なる電子楽器同士がメーカーの枠を超えて同時に鳴らせるようになった。またコンピュー ターと電子楽器をつなぐことが可能となり、コンピューター上で演奏データを作成し、MIDI を通じて電子楽 器を自動演奏させることが可能となった。机の上で音楽の最終形まで制作可能になったことから「Desk Top Music」と呼ばれ、音楽制作の現場を大きく変えることになった。 また 1990 年代大手パソコン通信ホストによりアマチュア・ミュージシャンによる MIDI データの流通が隆 盛を極めた。このような MIDI データの流通には GS 音源、XG 音源と呼ばれたデファクトスタンダードな音色 配置と、SMF(Standard MIDI File)と呼ばれた MIDI データを記憶する共通ファイル・フォーマットの存在 が貢献した。 1992 年通信カラオケの誕生によって MIDI は楽器業界以外にも活躍の場を得ることになる。MIDI データを 使った通信カラオケシステムは、従来のディスクメディアによるカラオケシステムより、新曲の制作・配信が圧 倒的に速く、内蔵曲数の制限も少なく、ランニングコストも安価になったことから、カラオケの低価格・大衆化 を大きく前進させた。また 1999 年 2 月の i モード・サービス開始などにより、コンテンツ・プロバイダのメ ニューサイトで着信メロディーの演奏データを課金のうえダウンロードするのが一般的となり、携帯電話向けコ ンテンツビジネスが急速に拡大した。着信メロディーの演奏データの実体は Standard MIDI File(SMF)で あり、MIDI データが携帯端末の世界でも活用された。 MIDI は演奏データ情報に留まらず、クロック情報、タイムコード情報なども扱えるためレコーディング・ス タジオの制作プロセスを大きく変革した。さらに MIDI の RP(推奨実施例)として MIDI Machine Control、 MIDI Show Control、MIDI Visual Control 等も制定され、マルチトラックレコーダーの機器制御、照明機 器の制御、映像機器の制御にも MIDI が使われるようになった。 1999 年には MIDI を USB ケーブルの中に通すことが可能となり、また 2015 年には Bluetooth Low Energy(BLE)が規格化され、 2016 -

Atari-ST-Internals.Pdf

INTERNALS The authoritative insider's guide By K. Gerits, L. Englisch, R. Bruckmann A Data Becker Book Published by Abacus Software Third Printing, July 1986 Printed in U.S.A. Copyright © 1985 Data Becker GmbH Merowingerstr.30 4000 Dusseldorf, West Germany Copyright © 1985 Abacus Software, Inc. P.O. Box 7219 Grand Rapids, MI 49510 This book is copyrighted. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Abacus Software or Data Becker, GmbH. Every effort has been made to insure complete and accurate information concerning the material presented in this book. However Abacus Software can neither guarantee nor be held legally responsible for any mistakes in printing or faulty instructions contained in this book. The authors will always appreciate receiving notice of subsequent mistakes. ATARI, 520ST, ST, TOS, ST BASIC and ST LOGO are trademarks or registered trademarks of Atari Corp. GEM, GEM Draw and GEM Write are trademarks or registered trademarks of Digital Research Inc. IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines. ISBN 0-916439-46-1 Table of Contents 1 The Integerated Circuits 1 1.1 The 68000 Processor 3 1.1.1 The 68000 Registers 4 1.1.2 Exceptions on the 68000 7 1.1.3 The 68000 Connections 7 1.2 The Custom Chips 13 1.3 The WD 1772 Floppy Disk Controller 20 1.3.1 1772 Pins 20 1.3.2 1772 Registers 24 1.3.3 Programming the FDC 25 1.4 The MFP 68901 28 1.4.1 68901 Connections 28 1.4.2 The MFP Registers 32 1.5 The 6850 ACIAs 41 1.5.1 The Pins of the 6850 41 1.5.2 The Registers of the 6850 44 1.6 The YM-2149 Sound Generator 48 1.6.1 Sound Chip Pins 50 1.6.2 The 2149 Registers and their Functions 52 1.7 I/O Register Layout of the ST 55 2 The Interfaces 65 2.1 The Keyboard . -

Australian Pinball Museum Newsletter

APR/MAY/JUN 2019 Australian Pinball Museum Newsletter Another 3 months have gone by so quickly. Here is an update of what has happened at Midget Hi-Ball. the museum in the past 3 months. Now at the museum! A fun 1930’s original pinball with an unusual round playfield. To keep up to date, like our Facebook page Manufactured by Peo Manufacturing to see everything as it happens at the Corporation in New York in 1932. museum and to also see interesting pieces of pinball history: facebook.com/PinballMuseum Follow our Instagram for pinball photos: @PinballMuseumAustralia Subscribe to our quarterly newsletter on our website: The new Black Knight is a fast playing game PinballMuseum.com.au/?p=Newsletter and is really addictive. You battle the Black Knight and all his minions. New Game Arrivals The centre of the playfield features the Black Knight who wields a flail and a shield, Black Knight: Sword of Rage by Stern. which he uses to block your shots. Good Luck. Manufactured by Genco in 1932. Game Line-up Changes A fun little pinball with a horseshoe at the top of the playfield. Interestingly the whole Singapore. cabinet is metal instead timber like most Manufactured in 1947 by United pinballs. This game is now at the museum! Manufacturing Company in Chicago USA. Our machine was made on the 2nd of December 1947! When it was released, this machine was $249.50 USD (equivalent to $2645 USD, $3850 AUD today). This machine was released at the same time as Gottliebs Humpty Dumpty - the pinball that started the flipper revolution. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

VORTEK™ V3 Multi-Game System System Manual 040-1001-01 Rev C

VORTEK™ V3 Multi-Game System System Manual 040-1001-01 Rev C ! Read this manual before use. ! Keep this manual with the machine at all times. www.globalvr.com http://service.globalvr.com [email protected] Phone: 408.597.3435 Fax: 408.597.3437 © 2006 Global VR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Operation Blockade, Infogrames, and the Infogrames logo are trademarks of Infogrames Entertainment. S.A. Beach Head 2000, Beach Head 2002, and Beach Head 2003: Desert War are trademarks of Digital Fusion Inc. and are used under license by Infogrames. VORTEK, GLOBAL VR, and the GLOBAL VR logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Global VR, Inc. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. Preface Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................................3 Safety..................................................................................................................................................................3 Precautions for Game Operation.........................................................................................................................3 Warnings.............................................................................................................................................................4 Environmental Conditions ..................................................................................................................................4