51. 'The Finger of God Is Here!' 1539

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

The Motivation for the Patronage of Pope Julius Ii

THE MOTIVATION FOR THE PATRONAGE OF POPE JULIUS II Christine Shaw As the head of the Western Church, Giuliano della Rovere, Pope Julius II (1503-13), has had his critics, from his own day to ours, above all for his role as ‘the warrior pope’. The aspect of his rule that has won most general approval has been his patronage of the arts. The complex iconography of some of the works Julius commissioned, particularly Raphael’s frescoes in the Vatican Stanze, and the scale of some of the projects he initiated – the rebuilding of St Peter’s, the development of the via Giulia, the massive and elaborate tomb Michelangelo planned to create for him – have provided fertile soil for interpretation of these works as expressions of Julius’s own ideals, aspirations, motives and self-image. Too fertile, perhaps – some interpretations have arguably become over-elaborate and recherchés. The temptation to link the larger than life character of Julius II with the claims for the transcendent power and majesty of the papacy embodied in the ico- nography and ideology of the works of art and writings produced in Rome during his pontificate, whether or not they were commissioned by the pope, has often proved irresistible to scholars. Some of the works associated with Julius can be read as expressions of certain conceptions of papal authority, and of the Rome of the Renaissance popes as the culmination of classical and Jewish, as well as early Christian history. But should they be read as Julius’s conception of his role as pope, his programme for his own papacy? Just because others identified him with Julius Caesar, or with Moses, does that mean that he saw himself as Moses, as a second Julius Caesar? There were plenty of learned men in Rome, ready to elabore theories of papal power which drew on different traditions and to fit Julius into them, just as they had fitted earlier popes and would fit later popes into them. -

Martin Luther’S New Doctrine of Salvation That Resulted in a Break from the Catholic Church and the Establishment of Lutheranism

DO NOW WHAT DOES THE WORD REFORM MEAN? WHAT DO YOU THINK IT MEANS REGARDING THE CHURCH? Learning Targets and Intentions of the Lesson I Want Students To: 1. KNOW the significance of Martin Luther’s new doctrine of salvation that resulted in a break from the Catholic church and the establishment of Lutheranism. 2. UNDERSTAND the way humanism and Erasmus forged the Reformation. 3. Analyze (SKILL) how Calvinism replaced Lutheranism as the most dynamic form of Protestantism. Essential Question. What caused the Protestant Reformation? REFORMATION RE FORM TO DO TO MAKE AGAIN BUT DO OVER/MAKE WHAT AGAIN?THE CHURCH! Definitions Protest Reform To express strong To improve by objection correcting errors The Protestant Reformation 5 Problems in the Church • Corruption • Political Conflicts Calls for Reform • John Wycliffe (1330-1384) – Questioned the authority of the pope • Jan Hus (1370-1415) – Criticized the vast wealth of the Church • Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) – Attacked corruption in the Church Corruption • The Church raised money through practices like simony and selling indulgences. Advantages of Buying Indulgences Go Directly to Heaven! • Do not go to Hell! • Do not go to Purgatory! • Get through Purgatory faster! • Do not pass Go! Martin Luther Who was Martin Luther? • Born in Germany in 1483. • After surviving a violent storm, he vowed to become a monk. • Lived in the city of Wittenberg. • Died in 1546. Luther Looks for Reforms • Luther criticized Church practices, like selling indulgences. • He wanted to begin a discussion within the Church about the true path to salvation. • Stresses faith over He nailed his Ninety- works, rejected church Five Theses, or as intermediary. -

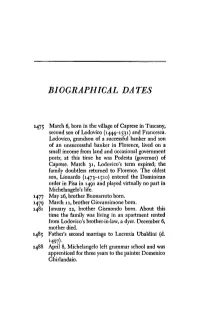

Biographical Dates

BIOGRAPHICAL DATES 1475 March 6, born in the village of Caprese in Tuscany, second son of Lodovico (1444-1531) and Francesca. Lodovico, grandson of a successful banker and son of an unsuccessful banker in Florence, lived on a small income from land and occasional government posts; at this time he was Podesta (governor) of Caprese. March 31, Lodovico's term expired; the family doubtless returned to Florence. The oldest son, Lionardo (1473-1510) entered the Dominican order in Pisa in 1491 and played virtually no part in Michelangelo's life. 1477 May 26, brother Buonarroto bom. 1479 March 11, brother Giovansimone born. 1481 January 22, brother Gismondo bom. About this time the family was living in an apartment rented from Lodovico's brother-in-law, a dyer. December 6, mother died. 1485 Father's second marriage to Lucrezia Ubaldini (d. M97)- 1488 April 8, Michelangelo left grammar school and was apprenticed for three years to the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. MICHELANGELO [1] 1489 Left Ghirlandaio and studied sculpture in the gar- den of Lorenzo de' Medici the Magnificent. 1492 Lorenzo the Magnificent died, succeeded by his old- est son Piero. 1494 Rising against Piero de' Medici, who fled (d. 1503). Republic re-established under Savonarola. October, Michelangelo fled and after a brief stay in Venice went to Bologna. 1495 In Bologna, carved three small statues which brought to completion the tomb of St. Dominic. Returned to Florence, carved the Cupid, sold to Baldassare del Milanese, a dealer. 1496 June, went to Rome. Carved the Bacchus for the banker Jacopo Galli. 1497 November, went to Carrara to obtain marble. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 06:48:52PM Via Free Access the POPE’S HOUSEHOLD and COURT in the EARLY MODERN AGE

THE EARLY MODERN WORLD Maria Antonietta Visceglia - 9789004206236 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 06:48:52PM via free access THE POPE’S HOUSEHOLD AND COURT IN THE EARLY MODERN AGE Maria Antonietta Visceglia Traditionally, the international historiography of the papal court in the Modern Age has concentrated on the origins and development of the curial bureaucracy,1 and on the relationship between this bureau- cracy and the Italian aristocracy. This practice was in line with the general debate about the rise of the modern state—of which the Eccle- siastical State could be considered an early, original model.2 Studies on the figure of the cardinal-nephew—the secretary of state3—and on pontifical diplomacy added a lively field of research still fitting into the above-mentioned debate.4 1 Peter Partner, The Pope’s Men: the Papal Civil Service in the Renaissance (Oxford 1990). 2 Paolo Prodi, Il sovrano pontefice. Un corpo e due anime: la monarchia papale nella prima età moderna (Bologna 1982) translated Susan Haskins, The Papal Prince, One Body and Two Souls: The Papal Monarchy in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge 1987). The bibliography on the themes of bureaucracy and Italian aristocracy of the papal state in the modern era is extensive. These research themes were established at the end of the 1990s with the reviews of Marco Pellegrini, ‘Corte di Roma e aris- tocrazie italiane in età moderna. Per una lettura storico-sociale della curia romana’, in: Rivista di storia e letteratura religiosa XXX (1994) pp. 543–602; Maria Antonietta Visceglia, ‘Burocrazia, mobilità sociale e patronage alla corte di Roma tra Cinque e Seicento. -

1. Humanism and Honour in the Making of Alessandro Farnese 35

6 RENAISSANCE HISTORY, ART AND CULTURE Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform of Politics Cultural the and III Paul Pope Bryan Cussen Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform Renaissance History, Art and Culture This series investigates the Renaissance as a complex intersection of political and cultural processes that radiated across Italian territories into wider worlds of influence, not only through Western Europe, but into the Middle East, parts of Asia and the Indian subcontinent. It will be alive to the best writing of a transnational and comparative nature and will cross canonical chronological divides of the Central Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period. Renaissance History, Art and Culture intends to spark new ideas and encourage debate on the meanings, extent and influence of the Renaissance within the broader European world. It encourages engagement by scholars across disciplines – history, literature, art history, musicology, and possibly the social sciences – and focuses on ideas and collective mentalities as social, political, and cultural movements that shaped a changing world from ca 1250 to 1650. Series editors Christopher Celenza, Georgetown University, USA Samuel Cohn, Jr., University of Glasgow, UK Andrea Gamberini, University of Milan, Italy Geraldine Johnson, Christ Church, Oxford, UK Isabella Lazzarini, University of Molise, Italy Pope Paul III and the Cultural Politics of Reform 1534-1549 Bryan Cussen Amsterdam University Press Cover image: Titian, Pope Paul III. Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy / Bridgeman Images. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 252 0 e-isbn 978 90 4855 025 8 doi 10.5117/9789463722520 nur 685 © B. -

Liberated from the Papacy a Journey with Scripture, Our Confessions, and Dr

Liberated from the Papacy A journey with Scripture, our Confessions, and Dr. Luther The Antichrist in the past, present, and future, around and among us as we commemorate the 500 th Anniversary of the Reformation In the name of Jesus. He would gladly have gone to Augsburg and Trent regardless of the edict. He lived in one In one of his last and most polemical works, of his favorite psalms, “I will not die, but live” Martin Luther sought, one last time, to (Ps. 118:17). unmask the evil sitting within the Church leading countless souls astray. Published on Neither was it the mockery opponents aimed the same day that the long desired church at his marriage to a runaway nun or how he council opened in the imperial city of Trent abandoned (in their view) his monastic vows (March 25, 1545), the title left no doubt where (even though he had actually been released Luther stood: Against the Roman Papacy: An from those vows by his ecclesiastical Institution of the Devil (LW 41:259-376). supervisor, John Staupitz). Scripture convinced him that marriage was a gift from God meant For nearly thirty years, Dr. Luther had been for all men and women because celibacy was preaching the gospel, thundering away at this an unkeepable vow for most everyone. great enemy. As he himself confessed in 1521 Likewise, he knew that monastic vows were a at the Diet of Worms, occasionally he had thing not commanded by God, and as he said spoken too harshly. While not always excusing continually in the Large Catechism , were every scatological reference or the mocking actually part of that self-chosen idolatry of the and sarcastic words he used, at the same papal system that ignored God’s actual time, it can be understood. -

Michelangelo and Pope Paul III, 1534-49

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2015 Michelangelo and Pope Paul III, 1534-49: Patronage, Collaboration and Construction of Identity in Renaissance Rome Erin Christine Sutherland Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons Recommended Citation Sutherland, Erin Christine, "Michelangelo and Pope Paul III, 1534-49: Patronage, Collaboration and Construction of Identity in Renaissance Rome" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 451. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/451 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Art History & Archaeology Dissertation Examination Committee: William E. Wallace, chair Marisa Bass Daniel Bornstein Nathaniel Jones Angela Miller Michelangelo and Pope Paul III, 1534-49: Patronage, Collaboration and Construction of Identity in Renaissance Rome by Erin Sutherland A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of -

The Petrine Ministry in a New Situation

The Petrine Ministry in a New Situation A Joint Statement on the Papacy by the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogue in Australia 2011 – 2016 The Petrine Ministry in a New Situation A Joint Statement on the Papacy by the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogue in Australia 2011 – 2016 © Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogue in Australia August 2016 Published by Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogue in Australia Secretary: Dr Josephine Laffin Australian Catholic University 116 George Street, Thebarton SA 5031 Front cover photo: Catacomb of Callixtus - The Good Shepherd [mid 3rd century], from Art in the Christian Tradition, a project of the Vanderbilt Divinity Library, Nashville, TN. http://diglib.library.vanderbilt.edu/ act-imagelink.pl?RC=54382 [retrieved 8 Aug 2016]. Original source: http://www.flickr.com/photos/ jimforest/2594526135/. Non-commercial use permitted. Back cover photo: Statuette of the Good Shepherd, early 4th century, Vatican Museums, Rome. Photo: Josephine Laffin. Used with permission. 26720 Designed & Printed by Openbook Howden Print & Design www.openbookhowden.com.au Preface The present document is the fruit of five years of dialogue (2011-2016). It is the eighth joint statement produced in the forty year history of the Lutheran–Roman Catholic Dialogue in Australia. The impetus for the present topic was the invitation of Pope John Paul II to engage in a patient and fraternal dialogue to find a way of exercising the Roman primacy which is open to a new situation. An early chapter of the document, “Talking Together in a New Situation,” sets out the new situation, not just for our respective churches, but also for our ecumenical relationship, which has evolved over these forty years. -

Great Heroes of the Great Reformation

Great Heroes (and Antiheroes) of the Great Reformation Unit 6: The Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation Cardinal Gasparo St. Ignatius de Loyola Contarini (1483—1542) (1491—1556) Reformation and Divisions in the 16th-Century Roman Catholic Church • Protestant Reformers (Luther, Melanchthon, Zwingli, Calvin, Knox, Bucer, Bullinger, Cranmer, etc.) • Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Society of Jesus (Jesuits) • Council of Trent (1545—1547; 1551—1552; 1562—1563) • Papacy • Revival in the Religious Orders • New Spirituality (Mystics) • Extra-European Roman Catholic Expansion The Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Most, strongly affected by Augustine, mostly agreed with the Reformers’ doctrine of justification by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. • Disagreed with the Reformers’ break from allegiance to the papacy. • Mixed on Eucharist (transubstantiation vs. consubstantiation vs. spiritual presence vs. pure symbol) and other liturgical matters. • Agreed with Reformers’ pursuit of moral reform. • Worked 1521—1541 “to reform the Church of Rome from within, towards a more Biblical theology and practice, and thus to win back the Protestants into the one true Church.” (Needham) • Key figures: Johann von Staupitz, Gasparo Contarini, Juan de Valdes, Albert Pighius, Jacob Sadoleto, Gregorio Cortese, Reginald Pole, Johann Gropper, Girolamo Seripando, Giovanni Morone • 1537, issued Consilium de Emendanda Ecclesia (“Consultation on Reforming the Church”)—forthright condemnation of the moral state of the Roman Church; pope refused to publish it; leaked out; spread rapidly; Roman Inquisition placed it on “Index of Forbidden Books” Leading Roman Catholic Evangelicals • Johannes von Staupitz (1460—1524), Luther’s spiritual guide in Augustinian order; agreed with almost all Luther’s doctrine but couldn’t break with papacy; yet all Staupitz’s writings were placed on Rome’s “index of forbidden books” in 1563. -

The Role of Indulgences in the Building of New Saint Peter's Basilica

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2011 The Role of Indulgences in the Building of New Saint Peter’s Basilica Ginny Justice Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, European History Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Justice, Ginny, "The Role of Indulgences in the Building of New Saint Peter’s Basilica" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 7. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/7 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Role of Indulgences in the Building of New Saint Peter’s Basilica A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies By Ginny Justice May 2011 Mentor: Dr. Kim Dennis Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 This is dedicated to my father Gerald Paul Pulley October 25, 1922 – March 31, 2011 ~ As we sped along the roads and byways of Italy heading toward Rome in 2003, my father said to me countless times, “Ginny, you are going to LOVE St. Peter’s Basilica! There is nothing else like it.” He was so right. Thank you for a lifetime of great road trips and beautiful memories, Dad. Until we meet again… 3 ● ● ● And when at length we stood in front with the majestic Colonnades sweeping around, the fountains on each side sending up their showers of silvery spray, the mighty Obelisk of Egyptian granite piercing the skies, and beyond the great façade and the Dome,—I confessed my unmingled admiration. -

RCIA, Session 07 HANDOUT

RCIA, Session #07: Timeline of Church History after the New Testament Era The Early Catholic Church (34 – 313 AD) 98 - 116 Trajan was emperor of Rome. Around this time the Roman Empire reached maximum size. c. 100 Christian Churches were established in Greece, North Africa, Italy, and Asia Minor. 100 - 165 St. Justin Martyr lived and was one of the first Christian apologists to offer a defense of Christianity. c. 100 The Romans built the first London Bridge across the Thames. c 110: Ignatius of Antioch uses the term Catholic Church in a letter to the Church at Smyrna (Date disputed, some insist it was a forgery written in 250 or later. Others insist he merely meant “catholic”, small “c”, as in Universal.) 122 Roman emperor Hadrian visited Britain and began construction of a wall and fortifications between northern England and Scotland. 132 Shimeon Bar-Kokhba and Rabbi Akiba Ben-Joseph led Jews in a revolt against Roman rule. They captured Jerusalem and created an independent state of Israel. 135 Julius Severus, formerly governor of Britain, crushed a revolt in Palestine. Final Diaspora (dispersion) of the Jews occurs. RCIA, Session #07 (Timeline of Church History after the New Test. Era) Page 1 The Diocese of Joliet c. 140 Shepherd of Hermas was written, describing a highly developed system of bishops, deacons, and priests. c. 144 Marcion founded an influential Christian sect which argued for the existence of two gods (one good, one evil) and for the rejection of the Old Testament. c. 150 The four “canonical” gospels were collected together.