Journal of Ukrainian Studies 20, Nos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ukrainian Weekly 2012, No.34

www.ukrweekly.com THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXX No. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 19, 2012 $1/$2 in Ukraine Ukraine wins 20 medals at Olympics Language expert at Harvard comments on Ukraine’s new law Following President Viktor Yanukovych’s signing on August 8 of the new law on the principles of state lan- guage policy, which was passed by the Verkhovna Rada on July 3, The Ukrainian Weekly contacted Prof. Michael S. Flier, an expert in Slavic linguistics at Harvard University, to comment on the significance of the new law and offer a prognosis for the Ukrainian language. Dr. Flier is the Oleksandr Potebnja Professor of Ukrainian Philology and director of the Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. Following are his answers to questions posed by Roma Hadzewycz. In your estimation, what is the significance of London2012.com President Viktor Yanukovych’s signing of the law on state language policy? Lightweight boxer Vasyl Lomachenko celebrates his Olympic gold medal in the 60-kg division. Let me begin by saying that the methods by which by Matthew Dubas two bronze medals. the new state language policy was introduced and Oleksandr Usyk won the gold medal in the 91-kg heavy- adopted reveal fundamental flaws in the Ukrainian PARSIPPANY, N.J. – Ukraine’s athletes collected 20 med- weight division, and celebrated his win in a truly Ukrainian political process itself, flaws that must be addressed if als – six gold, five silver and nine bronze medals – at the style – with a Hopak dance. -

The Annals of UVAN, Vol . V-VI, 1957, No. 4 (18)

THE ANNALS of the UKRAINIAN ACADEMY of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. V o l . V-VI 1957 No. 4 (18) -1, 2 (19-20) Special Issue A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko Ukrainian Historiography 1917-1956 by Olexander Ohloblyn Published by THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., Inc. New York 1957 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE DMITRY CIZEVSKY Heidelberg University OLEKSANDER GRANOVSKY University of Minnesota ROMAN SMAL STOCKI Marquette University VOLODYMYR P. TIM OSHENKO Stanford University EDITOR MICHAEL VETUKHIV Columbia University The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. are published quarterly by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S., Inc. A Special issue will take place of 2 issues. All correspondence, orders, and remittances should be sent to The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U. S. ПУ2 W est 26th Street, New York 10, N . Y. PRICE OF THIS ISSUE: $6.00 ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION PRICE: $6.00 A special rate is offered to libraries and graduate and undergraduate students in the fields of Slavic studies. Copyright 1957, by the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the U.S.} Inc. THE ANNALS OF THE UKRAINIAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IN THE U.S., INC. S p e c i a l I s s u e CONTENTS Page P r e f a c e .......................................................................................... 9 A SURVEY OF UKRAINIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY by Dmytro Doroshenko In tr o d u c tio n ...............................................................................13 Ukrainian Chronicles; Chronicles from XI-XIII Centuries 21 “Lithuanian” or West Rus’ C h ro n ic le s................................31 Synodyky or Pom yannyky..........................................................34 National Movement in XVI-XVII Centuries and the Revival of Historical Tradition in Literature ......................... -

Udc 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” Doi 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835

Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH, Olha KATRYCH, Jaroslaw CHACINSKI UDC 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” DOI 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835 Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH PhD hab. (Art), Associate Professor, Professor of the Departmentof Musical Medieval Studies and Ukrainian Studies.Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORСID: 0000-0002-5750-7940 Scopus-Author ID: 57221085667 Olha KATRYCH PhD (Art), Professor, Academic Secretary of the Academic Council, Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-2222-1993 Scopus-Author ID: 57221111370 ResearcherID: AAV-6310-2020 Jaroslaw CHACINSKI PhD (Humanities), Assistant Professor, Head of the Department of Music Art, Pomeranian Academy in Slupsk, 27 Partyzanów Street, Slupsk, Poland, postal code 76-200 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-3825-8184 Мирослава НОВАКОВИЧ доктор мистецтвознавства, доцент, професор кафедри музичної медієвістики та україністики Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ольга КАТРИЧ кандидат мистецтвознавства, професор, вчений секретар Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ярослав ХАЦІНСЬКИЙ доктор філософії (PhD humanities), доцент,завідувач кафедри музичного мистецтва Поморської академії,вул. Партизанів 27, м. Слупськ, Польща, індекс 76-200 ([email protected]) Bibliographic Description of the Article: Novakovych, M., Katrych, O. & Chacinski, J. (2021). The role of music culture in the processes of the Ukrainian nation formation in Galicia (the second half of the XIXth – the beginning of the XXth century). -

University of California UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer's Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov's Violin Sonata "Post Scriptum" and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8874s0pn Author Khomik, Myroslava Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction Of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts By Myroslava Khomik 2015 © Copyright by Myroslava Khomik 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ukrainian Identity in Modern Chamber Music: A Performer’s Perspective on Valentyn Silvestrov’s Violin Sonata “Post Scriptum” and its Interpretation in the Context of Ukrainian Chamber Works. by Myroslava Khomik Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Movses Pogossian, Chair Ukrainian cultural expression has gone through many years of inertia due to decades of Soviet repression and censorship. In the post-Soviet period, since the late 80s and early 90s, a number of composers have explored new directions in creative styles thanks to new political and cultural freedoms. This study focuses on Valentyn Silvestrov’s unique Sonata for Violin and Piano “Post Scriptum” (1990), investigating its musical details and their meaning in its post- Soviet compositional context. The purpose is to contribute to a broader overview of Ukraine’s classical music tradition, especially as it relates to national identity and the ii current cultural and political state of the country. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1996, No.5

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE: ^ Primakov travels to Kyiv to fay groundwork for Yeltsin visit - page 3. e Radio Canada International saved by Cabinet shuffle - page 4. 9 Washington Post correspondent shares impressions of Ukraine - page 5. THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXIV No. 5 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 1996 S1.2542 in Ukraine Ukraine's coal miners stage strike Parliament cancels moratorium to demand payment of back wages on adoptions, sets procedures by Marta Kolomayets during this harsh winter - amidst condi by Marta Kolomayets children adopted by foreigners through Kyiv Press Bureau tions of gas and oil shortages - and Kyiv Press Bureau Ukrainian consular services until they should be funded immediately from the turn 18 and forbids any commercial for KYIV - Despite warnings of mass state budget. KYIV - The Parliament on January 30 eign intermediaries to take part in the strikes involving coal mines throughout lifted a moratorium on adoption of As The Weekly was going to press, adoption process. Ukraine, Interfax-Ukraine reported that Ukrainian children by foreigners and Coal Industry Minister Serhiy Polyakov The law, which takes effect April 1, as of late Thursday evening, February I, voted to establish a new centralized mon had been dispatched to discuss an agree will closely scrutinize the fate and workers from only 86 mines out of 227 ment with strike leaders. According to itoring agency that will require all adop whereabouts of Ukraine's most precious had decided to walk out. They are Interfax-Ukraine, the Cabinet of Ministers tions in Ukraine to pass through, the resource - its children. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2012, No.52-53

www.ukrweekly.com ХРИСТОС НАРОДИВСЯ! CHRIST IS BORN! THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXX No. 52-53 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY DECEMBER 23-DECEMBER 30, 2012 $1/$2 in Ukraine Self Reliance New York presents Yanukovych cancels trip to Moscow $25,000 for Holodomor Memorial as Customs Union membership looms by Zenon Zawada experts and people familiar with the situa- Special to The Ukrainian Weekly tion spoke of uniting with Moscow as a nearly resolved matter.” KYIV – Ukraine came as close as ever The newspaper described a Kremlin this week to losing its independence as arrangement that resembled a scam. The President Viktor Yanukovych was within Russians arranged just 15 minutes of dis- hours of signing away Ukraine’s Euro- cussion between the two presidents before integration future in Moscow, reported the the scheduled signing, preventing any Kommersant-Ukrayina newspaper, a Kyiv- attempt by Mr. Yanukovych to negotiate based business daily published in the only partial conformity to the Customs Russian language. Union, which was his administration’s stat- At midnight at December 18, he can- ed goal. No advisors were invited to the celed a trip that was to take place the fol- 15-minute meeting. lowing afternoon to the Kremlin, where Only afterwards did the Kremlin sched- Russian President Vladimir Putin was wait- ule talks between the two delegations, ing for him with a stack of documents that including leading ministers, a scenario that would have sealed Ukraine’s membership Kommersant described as “unprecedented in the Customs Union, a precursor to the for international meetings.” In the days Eurasian Union that is aimed at reviving leading up to the trip, its status had been the Russian empire. -

TABLE of CONTENTS Libraries (ACRL), Which Is One of Several Divisions of the American Li- Brary Association (ALA)

MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR This year has been an extremely active one for the Slavic and East European Section (SEES) of the Association of College and Research TABLE OF CONTENTS Libraries (ACRL), which is one of several divisions of the American Li- brary Association (ALA). Major activities include: 1) the upcoming SEES program at the 2010 ALA Annual Conference in Washington, D.C.; 2) the implementation of the 2009–2010 SEES Action Plan, which involved, most significantly, a joint SEES/AAASS sponsored roundtable at the 2009 AAASS National Convention in Boston; 3) new digital projects of the Message from the Chair. ................................................................... 2 Access and Preservation (A&P) Committee; 4) the work of a special joint SEES/WEES ad-hoc committee to explore a potential merger of the two Message from the Editor. .................................................................. 6 sections; 5) updates to the Slavic cataloging manual by members of the Automated Bibliographic Control (ABC) Committee; and 6) personnel . I. CONFERENCES and format changes to the SEES newsletter. In 2009 SEES membership continued its gradual decline at the same rate (6 percent) as ACRL as a whole. At year’s end the total number of ALA Annual Meeting................................................................ 7 SEES members was 184. The data show a significant amount of turnover; while a number of SEES members did not renew their membership, the ALA Midwinter Meeting......................................................... 1 3 number of new members also increased in comparison with the previous year. Although SEES is always sad to see members leave the Section, we AAASS National Meeting....................................................... 2 2 are encouraged by the number of new members interested in exploring opportunities in SEES. -

Culture and Customs of Ukraine Ukraine

Culture and Customs of Ukraine Ukraine. Courtesy of Bookcomp, Inc. Culture and Customs of Ukraine ADRIANA HELBIG, OKSANA BURANBAEVA, AND VANJA MLADINEO Culture and Customs of Europe GREENWOOD PRESS Westport, Connecticut • London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Helbig, Adriana. Culture and customs of Ukraine / Adriana Helbig, Oksana Buranbaeva and Vanja Mladineo. p. cm. — (Culture and customs of Europe) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–313–34363–6 (alk. paper) 1. Ukraine—Civilization. 2. Ukraine—Social life and customs. I. Buranbaeva, Oksana. II. Mladineo, Vanja. III. Title. IV. Series. DK508.4.H45 2009 947.7—dc22 2008027463 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2009 by Adriana Helbig, Oksana Buranbaeva, and Vanja Mladineo All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2008027463 ISBN: 978–0–313–34363–6 First published in 2009 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The authors dedicate this book to Marijka Stadnycka Helbig and to the memory of Omelan Helbig; to Rimma Buranbaeva, Christoph Merdes, and Ural Buranbaev; to Marko Pećarević. This page intentionally left blank Contents Series Foreword ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xiii Chronology xv 1 Context 1 2 Religion 30 3 Language 48 4 Gender 59 5 Education 71 6 Customs, Holidays, and Cuisine 90 7 Media 114 8 Literature 127 viii CONTENTS 9 Music 147 10 Theater and Cinema in the Twentieth Century 162 Glossary 173 Selected Bibliography 177 Index 187 Series Foreword The old world and the New World have maintained a fluid exchange of people, ideas, innovations, and styles. -

Memory Politics: the Use of the Holodomor As a Political And

Memory Politics: The Use of the Holodomor as a Political and Nationalistic Tool in Ukraine By Jennifer Boryk Submitted to Central European University Nationalism Studies Program In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Advisor: Professor Maria Kovacs Budapest, Hungary 2011 CEU eTD Collection Abstract This thesis serves as an analysis of the construction and use of the Holodomor as the defining cornerstone of Ukrainian national identity, and the creation of a victim narrative through this identity. The thesis addresses the steps taken by Viktor Yushchenko in Ukraine to promote this identity, constructed in the diaspora, by seeking the recognition of the Holodomor as genocide by Ukraine‘s population, as well as the international community. The thesis also discusses the divergent views of history and culture in Ukraine and how these differences hindered of acceptance of Viktor Yushchenko‘s Holodomor policies. CEU eTD Collection Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 1 The Trials of Nation Building ............................................................................................................... 3 Chapter One: The National Identity Formula ...................................................................................... 10 1.1 Creation of a Collective Narrative .............................................................................................. -

Donbas in Flames

GUIDE TO THE CONFLICT ZONE This publication is the result of work of a group of authors of various competencies: investigative journalism, politology, geography, and history. Written as a kind of vade mecum, this guidebook will familiarize the reader with the precursors, problems, terminology, and characteristics of the war in the Donbas. The book is targeted at experts, journalists, and representatives of international missions working in Ukraine. It will also interest a wide range of readers trying to understand and develop their own opinion on the situation in the east of Ukraine. The electronic version of this publication can be downloaded from https://prometheus.ngo/donbas-v-ogni Donbas In Flames УДК 908(477.61/.62-074)”2014/…”(036=111) Guide to the conflict zone ББК 26.89(4Укр55) Lviv, 2017 Д67 Editor: Alina Maiorova Authors: Mykola Balaban, Olga Volyanyuk, Christina Dobrovolska, Bohdan Balaban, Maksym Maiorov English translation: Artem Velychko, Christina Dobrovolska, Svitlana Kemblowski, Anna Shargorodskaya, Andrii Gryganskyi, Max Alginin Design: Lukyan Turetsky Activity supported by the Security Environment Canada Fund for Local Initiatives Research Center © 2017 “Prometheus” NGO Activité réalisée avec l’appui du Fonds canadien d'initiatives locales Content Foreword. When the truth is the best weapon 5 Chapter 1. Donbas - The panoramic picture 7 Donbas on the Map of Ukraine 7 As Seen by Analysts and Journalists 10 Donbas (Un)Known to the World 14 Chapter 2. Could the War be Avoided? 17 Ukrainian land 17 Rust Belt 20 Similar and different 22 Voting Rights 25 Unsolicited patronage 26 Chapter 3. Chronicles of War 31 End of February 2014 31 March 2014 32 April 2014 33 May 2014 36 June 2014 38 July 2014 39 August 2014 41 Beginning of September 2014 42 September 2014 - February 2015 42 From February 2015 to this day 44 Chapter 4. -

Bishop Borys Gudziak Visits His Parish in Syracuse

Part 2 of THE YEAR IN REVIEW pages 5-12 THEPublished U by theKRAINIAN Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal W non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXXI No. 3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 20, 2013 $1/$2 in Ukraine New chair of Ukraine’s National Bank Mykhailo Horyn dies at 82 is another friend of the “family” Leading rights activist was a founder of Rukh Yanukovych vowed a “government of pro- by Zenon Zawada PARSIPPANY, N.J. – Mykhailo Horyn, Special to The Ukrainian Weekly fessionals” to replace what he alleged was an incompetent government under former a leading Ukrainian dissident during KYIV – The family business empire of Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, now the Soviet era and a human rights Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych imprisoned. That promise drew millions of activist who was a member of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group and a retained its control of Ukraine’s central voters to cast their ballots for Mr. founder of Rukh, the Popular bank, critics said, when Parliament Yanukovych. Movement of Ukraine, died in the approved on January 11 the nomination of Yet Mr. Sorkin didn’t have any formal early morning hours of January 13 Ihor Sorkin, 45, as chair of the National financial education until 10 years after his after a serious illness. He was 82. Bank of Ukraine (NBU). first banking appointment, earning a mas- A Ukrainian patriot who worked Mr. Sorkin has long ties to Donbas busi- ter’s degree in banking from Donetsk tirelessly for freedom and human and ness clans, having earned his first banking National University in 2006. -

Tocc0177notes.Pdf

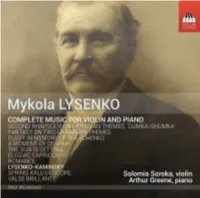

MYKOLA LYSENKO: VIOLIN MUSIC by Lyubov Kyjanovska and Solomia Soroka Mykola Lysenko (1842–1912) is considered the father of Ukrainian classical music. He was an excellent concert pianist who received a first-rate musical education. He studied with a Czech pianist at his home in Kyiv before attending the Leipzig Conservatoire, where his most prominent teachers included Ferdinand David, Ignaz Moscheles, Carl Reinecke and Ernst Wenzel. His statue now stands outside the Opera House in Kyiv, and the music conservatoire of L’viv bears his name. There has recently been a revival of his music in Ukraine, but outside Ukraine his music is practically unknown. Lysenko wrote in a late-Romantic style common to many late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth- century composers, with an important difference: his Ukrainian identity was a vital part of his music. For example, he had the chance of what would have been a career-milestone performance of his opera Taras Bulba in Moscow but because of the Ems Ukaz of 1876, which prohibited any publication, stage performance, lecture, or imported publication in the Ukrainian language,1 it would have had to be performed in Russian instead of the original Ukrainian – and Lysenko refused to countenance the preparation of a Russian version of the libretto.2 Most importantly, he was the first ethnographer of Ukrainian music, and he used the results of his research to varying degrees throughout all his best works. Lysenko was born in Hrymky, a village near the Dnipro River between Kyiv and Dnipropetrovsk on 22 March [10 March Old Style] 1842. His father came from an old aristocratic family, tracing its lineage back to the Cossacks of the seventeenth century.