Rameau's Dardanus, Notes for the English Touring Opera Production

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wednesday Playlist

September 25, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “Art and life are not two separate things.” — Gustav Mahler Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Boston Symphony/Davis Philips 446 160 028944616026 Awake! 00:11 Buy Now! Elgar The Sanguine Fan, Op. 81 London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 63133 077776313320 00:30 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Quartet No. 2 in E flat, K. 493 Bronfman/Zukerman/Marks/Forsyth RCA Red Seal 88697160442 886971604429 01:00 Buy Now! Gershwin Lullaby for Strings Cincinnati Pops/Kunzel Telarc 80503 089408050329 01:10 Buy Now! Bach English Suite No. 4 in F, BWV 809 Glenn Gould Sony 52606 n/a 01:28 Buy Now! Strauss, R. Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme Suite Chicago Symphony/Reiner RCA 5721 07863557212 01:59 Buy Now! Mozart Overture ~ The Magic Flute, K. 620 Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields/Marriner EMI 47014 077774701426 Virgin Classics 02:07 Buy Now! Rameau Fourth Concert (for harpsichord and strings) Trio Sonnerie 90749 07567907492 Digital 02:19 Buy Now! Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73 "Emperor" Arrau/Dresden State Orchestra/Davis Philips 416 215 028941621528 03:01 Buy Now! Mascagni Intermezzo ~ Cavalleria rusticana Philadelphia Orchestra/Ormandy Sony 48260 07464482602 03:05 Buy Now! Shostakovich Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat, Op. 107 Kanneh-Mason/CBSO/Grazinyte-Tyla Decca 483 2948 028948329489 03:38 Buy Now! Telemann Paris Quartet No. 10 Kuijken Bros/Leonhardt Sony 63115 074646311523 03:59 Buy Now! Chopin Scherzo No. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1954-1956

contltictA me «L$o4tim ^ymfmtmu &^cAe4t^a RCA Victor recreates all the eloquence of his interpretations in these brilliant "New Orthophonic ' High Fidelity recordings **Berlioz:The Damnation of Faust (complete)—Suzanne Danco, Soprano; David Poleri, Tenor; Martial Singher, Baritone **Berlioz: Romeo and Juliet (complete)—Margaret Roggero, Contralto; Leslie Chabay, Tenor; Yi-Kwei Sze, Bass **Brahms: Piano Concerto No. 2, in B Flat, op. 83—Artur Rubinstein, Piano *Beethoven: Symphony No. 7, in A, op. 92 **Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 2, in F Minor. **Saint-Saens: Piano Concerto No. 4, in C Minor—Alexander Brailowsky, Piano. **"New Orthophonic' High Fidelity. *High Fidelity. rcaVictor D I D MUSIC ill ^i1 s i ? » "• I *> ". :, Pv ^H—JL i i ~.~z~ BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA CHARLES MUNCH, Music Director Berkshire Festival, Season 1955 (EIGHTEENTH SEASON) TANGLEWOOD, LENOX, MASSACHUSETTS FIRST WEEK Concert Bulletin, with historical and descriptive notes by John 1\. Burk copyright. l955, by boston symphony orchestra, inc. Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Henry B. Cabot, President Jacob J. Kaplan, Vice-President Richabd C. Paine, Treasurer Talcott M. Banks, Jr. \lvan I. Fuller C. D. Jackson Charles H. Stockton John Nicholas Brown Francis W. Hatch Michael T. Kelleher Ldward A. Taft Theodore P. Ferris Harold D. Hodgkinson Palfrey Perkins Raymond S. Wilkins Oliver Wolcott Trustees Emeritus Philip B. \lleiv M. A. DeWolfe Howe N. Penrose Hallowell Lewis Perry Tanglewood Advisory Committee \i.\n J. Blai Henry W. Dwight F. Anthony Hanlon George E. Mole Lenges Bi m George W. Edman Lawrence K. Miller Whitney S. Stoddard Jesse L. Thomason Bobert K. Wheeler H. -

Dardanus De Jean-Philippe Rameau Direction Musicale Emmanuelle Haïm Mise En Scène Claude Buchvald Chorégraphie Daniel Larrieu Chœur Et Orchestre Du Concert D’Astr Ée

Dossier pédagogique Opéra / Nouvelle production DARDANUS DE JEAN-PHILIPPE RAMEAU DIRECTION MUSICALE EMMANUELLE HAÏM MISE EN SCÈNE CLAUDE BUCHVALD CHORÉGRAPHIE DANIEL LARRIEU CHŒUR ET ORCHESTRE DU CONCERT D’ASTR ÉE Du 16 au 24 octobre 2009 Contacts Service des relations avec les publics [email protected] Dossier réalisé avec la collaboration de Sébastien Bouvier, enseignant missionné à l’Opéra de Lille Septembre 2009 Sommaire Préparer votre venue à l’Opéra 3 DARDANUS Résumé 4 Synopsis 5 La musique baroque 6 La tragédie lyrique ou « tragédie en musique » 7 Les instruments baroques 10 La danse dans l’opéra baroque 12 Guide d’écoute 14 Vocabulaire 21 Références 22 DARDANUS À L’OPÉRA DE LILLE Distribution 23 Notes d’intention de mise en scène 24 Repères biographiques 25 POUR ALLER PLUS LOIN La Voix à l’opéra 27 Qui fait quoi à l’opéra ? 29 L’Opéra de Lille, un lieu, une histoire 30 ANNEXES Les instruments de l’orchestre 34 Annexe : frise chronologique sur Rameau et son époque 35 2 Préparer votre venue Ce dossier vous aidera à préparer votre venue avec les élèves. L’équipe de l’Opéra de Lille est à votre disposition pour toute information complémentaire et pour vous aider dans votre approche pédagogique. Si le temps vous manque, nous vous conseillons, prioritairement, de : - lire la fiche résumé et le synopsis détaillé - faire une écoute des extraits représentatifs de l’opéra (guide d’écoute) Recommandations Le spectacle débute à l’heure précise, 20h ou 16h le dimanche. Il est donc impératif d’arriver au moins 30 minutes à l’avance, les portes sont fermées dès le début du spectacle. -

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, And

Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte et Aricie Author(s): Charles Dill Source: Journal of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Winter 2002), pp. 433- 476 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the American Musicological Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jams.2002.55.3.433 . Accessed: 04/09/2014 11:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and American Musicological Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the American Musicological Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.104.46.206 on Thu, 4 Sep 2014 11:26:08 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Rameau's Imaginary Monsters: Knowledge, Theory, and Chromaticism in Hippolyte etAricie CHARLES DILL dialectic existed at the heart of Enlightenment thought, a tension that sutured instrumentalreason into place by offering the image of its irra- JL A1tional other. Embedded within the rationalorder of encyclopedicen- terpriseslay the threat posed by superstition,both religious and unlettered; contained and controlled by the solid foundations of social contractswas the disturbing image of chaos, evoked musically by Jean-FeryRebel and Franz Joseph Haydn, and among the nobly formed figures of humankind and nature there lurked deformity and aberration,there lurked the monster. -

© in This Web Service Cambridge University

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02156-3 - Dramatic Expression in Rameau’s Tragédie en Musique: Between Tradition and Enlightenment Cynthia Verba Index More information Index accompanied recitative chromatics, 27, 38, 62, 68, 69, 72, 75–76, 78, as tonal anchors, 32 80, 86, 88–89, 92–93, 140, 147, 148, in Dardanus, 131, 194–196, 203 169, 175, 176, 179, 185, 186, 193, 196, in Hippolyte et Aricie, 66, 67, 72, 79–80, 90, 210, 244, 249, 286, 291 115 classical models of tragedy, 85, 181 (see also in Les Bor´eades, 218 Aristotelian poetics) in Zoroastre, 292–295 Cohen, David E., 30–31 airs contrary duos, 67–68, 69–71, as tonal anchors, 32, 34, 36 251–253 in Castor et Pollux, 124 Cowart, Georgia, 8–10 in Dardanus, 129, 196–199, 291–292 in Hippolyte et Aricie, 51–53, 54–62, 65, 74, da capo arias, 4, 144, 163, 183–188, 200–203, 79, 80–84, 86, 90–93 210, 212, 247–249 in Les Bor´eades, 169, 171–172, 175, 178–179, terminology, x 214–216, 217–218 D’Alembert,JeanleRond,2–3 in Lully’s operas, 7, 17–18 deities in Zoroastre, 134, 137, 140–141, 147, interventions, imposed by deities, 84, 148–149, 152, 153–154, 155, 203–207 89–90, 116, 117, 118, 119, 123–124, terminology, x, 56 127, 129, 145, 161, 170, 175, 177, 179, Allanbrook, Wye Jamison, 32 301–302 ancien r´egime, 1, 7, 9–11, 14, 16, 108, 109, 314, invocations, addressing deities, 79–84, 316–317 85–89, 112, 115, 116, 125, 146–147, Anthony, James, 16, 20, 21 152–153, 174, 200–203 ariettes, 117, 124, 144, 163–167, 170, 172, 176, Diderot, Denis, 2, 3, 20, 31–32 302 Dill, Charles, 5, 8, 19, 21–22, 44, -

Rameau, Jean-Philippe

Rameau, Jean-Philippe (b Dijon, bap. 25 Sept 1683; d Paris, 12 Sept 1764). French composer and theorist. He was one of the greatest figures in French musical history, a theorist of European stature and France's leading 18th-century composer. He made important contributions to the cantata, the motet and, more especially, keyboard music, and many of his dramatic compositions stand alongside those of Lully and Gluck as the pinnacles of pre-Revolutionary French opera. 1. Life. 2. Cantatas and motets. 3. Keyboard music. 4. Dramatic music. 5. Theoretical writings. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY GRAHAM SADLER (1–4, work-list, bibliography) THOMAS CHRISTENSEN (5, bibliog- raphy) 1. Life. (i) Early life. (ii) 1722–32. (iii) 1733–44. (iv) 1745–51. (v) 1752–64. (i) Early life. His father Jean, a local organist, was apparently the first professional musician in a family that was to include several notable keyboard players: Jean-Philippe himself, his younger brother Claude and sister Catherine, Claude's son Jean-François (the eccentric ‘neveu de Rameau’ of Diderot's novel) and Jean-François's half-brother Lazare. Jean Rameau, the founder of this dynasty, held various organ appointments in Dijon, several of them concurrently; these included the collegiate church of St Etienne (1662–89), the abbey of StSt Bénigne (1662–82), Notre Dame (1690–1709) and St Michel (1704–14). Jean-Philippe's mother, Claudine Demartinécourt, was a notary's daughter from the nearby village of Gémeaux. Al- though she was a member of the lesser nobility, her family, like that of her husband, included many in humble occupations. -

Papilio Dardanus, Brown, and Papilio Glaucus, Linn

THE GENETICS OF SOME MIMETIC FORMS OF PAPILIO DARDANUS, BROWN, AND PAPILIO GLAUCUS, LINN. By C. A. CLARKE AND P. M. SHEPPARD The Universit),, Liverpool. (Received, june 3, 1957) Bates (I862) put [brward the hypothesis that some anilnals obtain protection from ~heir predators by resembling or mimicking unpalatable or otherwise protected species and in consequence are mistaken for them by the predators. Mtiller (1879) suggested that even protected species would gain by resembling one another. These two hy-po- theses have been discussed and enlarged upon by many people but comparatively little work has been done either to determine the extent of the protection so afforded or to ascertain the evolutionary steps by which the mimicry has been brought about. The genetic work that has been done in this field (m.ostly with butterflies) suggests that the differences between various mimetic and non-mimetic forms of polymorphic butterflies are controlled by simple mendelian mechanisms, often a single allelomorphic difference. This has led some people, notably Punnett (I915) and more recently Goldschmidt (i945) to maintain that, because the allelomorph must have arisen at a single step by mutation, the mimetic resemblance must also have arisen fully developed from the beginning. This view leads to ~various theoretical difficulties which have been discussed by Ford (1953). Because of these, both Fisher (1930) and Ford (Carpenter and Ford 1933, Ford 1937) take the view that when a mutant pro- ducing some mimetic resemblance is established in a population the resemblance is improved by selection for a gene-complex in which the original effect of the gene is altered towards more perfect mimicry. -

The Genetics of Papilio Dardanus, Brown. 11. Races Dardanus, Polytrophus, Meseres, and Tibullus

THE GENETICS OF PAPILIO DARDANUS, BROWN. 11. RACES DARDANUS, POLYTROPHUS, MESERES, AND TIBULLUS C. A. CLARKE AND P. M. SHEPPARD Departments of Medicine and Zoology, University of Liuerpool, England Received September 28, 1959 N Part I (CLARKEand SHEPPARD1959) we described the genetics of P. dar- Idanus race cenea from South Africa. The present paper concerns four other races of the butterflydardanus, polytrophus, meseres and tibullus. The map (Figure I) shows the distribution of these and their geographical relationships FIGURE1.-Distribution and geographical relationship of P. dardanus races. 440 C. A. CLARKE AND P. M. SHEPPARD with P. dardanus cenea. In addition the areas inhabited by the Madagascan race meriones and the Abyssinian race antinorii are indicated, and these forms will be the subject of a separate paper (Part 111). RACE DARDANUS This has the most extensive range of any of the races of P. dardanus. It is found down the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Angola, and spreads east- wards towards Uganda and Tanganyika Territory to Lake Victoria. In these areas it merges into the transitional race meseres. In the western part of its range the female is almost invariably the mimetic form hippocoon, and this closely resembles the form hippocoonides already described under race cenea from South Africa (Part I). In race dardanus we have bred hippocoon both from the eastern and western parts of its range and have also investigated f. trophonissa, f. niobe and f. plane- moides. The mimetic form cenea has not so far appeared in our material but we have carried out a race cross using this form from South Africa (see below). -

DARDANUS Jean-Philippe Rameau

L’Opéra Royal du Château de Versailles DARDANUS Jean-Philippe Rameau Collection Versailles Alpha 951 Enchanter le monde Depuis 1987, la Fondation Orange encourage la pratique collective de la musique vocale dans les répertoires classiques, jazz et musique du monde. Elle contribue à la découverte de nouvelles voix, à la formation et l’insertion professionnelle de jeunes chanteurs, à l’émergence d’ensembles vocaux. Elle soutient de nombreux festivals et accompagne les maisons d’opéras qui développent des projets sociaux et pédagogiques desti- nés à sensibiliser des nouveaux publics à la création musicale. La Fondation Orange est le mécène de Pygmalion ; elle apporte son soutien à toutes ses activi- tés musicales : création, diffusion et enregistrement discographique The world in harmony Since 1987, the Orange Foundation has been encouraging vocal music groups in the classical, jazz and world music repertoires. The foundation contributes to the discovery of new voices, the training and integration of young singers into the job market, and the emergence of vocal groups. It provides support to numerous festivals and helps opera companies that develop social and educational projects to raise more people’s awareness of musical creation. The Orange Foundation supports Pygmalion in all of it’s musical activities: creation, distribution and recordings. ~ 2 ~ DARDANUS Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683 - 1764) CD1 *********************** Prologue 1. Ouverture 4'13 Scène 1 2. « Régnez , Plais irs, régnez » 1'56 3. Air gay et gracieux /Air pour la Jalousie et sa suite 0'59 4. « Je ve ux que sous mes lois »/« Plais irs, enchaînez -les » 2'36 5. Air vif pour les Plaisirs 1'05 6. -

Baroque Opera Lecture Long Version Revised August 2020 1 Teatro San

Baroque Opera lecture Long Version Revised August 2020 1 Teatro San Samuele. Painting by Bella 2 Plan of the boxes in the Theatre in Lucca 1751. Added in the libretto for La Semiramide Riconosciuta. 3 List of names attached to image 2 4 Enrico Wanton by Zaccaria Seriman. Illustration by Fossati. Venice 1749 5 The Boxes in San Carlo Theatre, Naples. 6 Amphitheatre in Verona being used as a temporary theatre. Painting by Marco Marcola. 1771 7 Plan of the Salles des Spectacles at the Tuilleries, Paris 8 A Petit Maître at the Paris theatre. 9 A box at the Opéra. Etching by J. B. Patas after J. M. Moreau 1789 10 Estates Theatre, Prague 11 Queen’s Theatre London after 1707/8 12 ‘Getting into the pit’ 13 ‘Laughing audience’ by Hogarth 14 ‘Comedy in the Country’ by Thomas Rowlandson c. 1810 15 ‘Tragedy in London’ by Rowlandson c.1810 16 Price Riot at Covent Garden. 1763 17 John Bull at the Opera by Rowlandson 1811. 18 Bayreuth. View of the stage and pit 19 Bayreuth. View of Auditorium 20 Bayreuth. The Margravine’s Box 21 Bayreuth. Above the Margravine’s Box 22 Theatre at Versailles designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel 23 The Queen’s Theatre in the Trianon. 1780 24 Theatre at Eszterháza—not really 25 Cesky Krumlov. View of the stage 26 Cesky Krumlov. View of the stage 27 Cesky Krumlov. View of the princely box 28 Cesky Krumlov. View during a performance of Tito Vespasiano by Hasse 29 Bad Lauchstädt. View of stage. 30 Bad Lauchstädt. -

Print 557490 Bk Rameau US

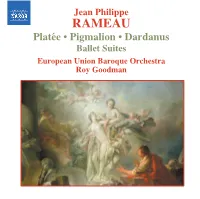

557490 bk Rameau US 5/7/05 4:31 pm Page 4 Roy Goodman Jean Philippe Since August 2004 Principal Conductor of Holland Symfonia, Roy Goodman is also Conductor and Artistic Leader of the Bachkoor Holland, and Principal Guest Conductor of the English Chamber Orchestra and of the Norrlands Opera in Sweden. He has worked as guest conductor with ninety orchestras and opera companies RAMEAU worldwide, and is well known for his work as director and founder of the Brandenburg Consort, co-founder with Peter Holman of the Parley of Instruments, Principal Conductor of the Hanover Band, Music Director of the European Union Baroque Orchestra from 1989 to 2004 and Music Director of the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra in Platée • Pigmalion • Dardanus Winnipeg from 1999 to 2005. Born in 1951, he was a treble chorister at King’s College, Cambridge. In 1970 he was made a Fellow of the Royal College of Organists in London and he is also a Doctor of Music and Fellow of the Royal College of Music. After early years as a school teacher, he later became Director of Music at the University Ballet Suites of Kent and Director of Early Music Studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London. From 1977 Goodman worked throughout Europe as a baroque violinist and concertmaster with leading conductors, turning to an international career as a conductor himself after success in 1989 with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra. His European Union Baroque Orchestra recordings thereafter with the Hanover Band include première performances on historic instruments of the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Weber, as well as fourteen symphonies by Roy Goodman Mendelssohn and sixty symphonies by Haydn. -

Orchestre Des Arts Florissants Jonathan Cohen, Chef Associé, Direction Anna Reinhold, Bas-Dessus

5e édition Orchestre des Arts Florissants Jonathan Cohen, chef associé, direction Anna Reinhold, bas-dessus Airs et danses de Rameau Jean-Philippe Rameau (1683-1764) --- Mercredi 25 juin 2014 - 20 h 30 Programme Hippolyte et Aricie Ouverture Entrée pour les Habitants des bois (Prologue) – instrumental Premier et deuxième Menuet (Prologue, c.1) – instrumental Air d’Aricie “Temple sacré” (Acte I, sc.1) Les Indes galantes Ouverture Air pour les Esclaves Africains (Le Turc généreux, sc.6) – instrumental Premier et deuxième Rigaudon (Le Turc généreux, sc.6) – instrumental Air d’Emilie “Fuyez, vents orageux” (Le Turc généreux, sc.6) Premier et deuxième Tambourin (Le Turc généreux, sc.6) – instrumental Castor et Pollux Ouverture Prélude du choeur “Que tout gémisse”(Acte I, sc.1) – instrumental Air tendre de Télaïre “Quelle faible victoire” (Acte I, sc.2) Air de Télaïre “Tristes apprêts” (Acte I, sc.3) - Entracte - Le Temple de la Gloire Air tendre pour les Muses (Prologue, sc.3) – instrumental Dardanus Chaconne (Acte V, scène dernière) – instrumental Les Fêtes d’Hébé Air de l’Amour “Vole, Zéphir” (Prologue) Air gracieux pour Zéphir et les Grâces (Prologue, sc.5) – instrumental Air tendre (La Musique, sc.5) – instrumental Premier et deuxième Rigaudon (La Musique, sc.5) – instrumental L’Hymen - Chaconne (La Musique, sc.5) – instrumental Naïs Musette tendre (Acte III, sc.6) – instrumental Air d’une bergère “Je ne sais quelle ardeur me presse” (Acte III, sc.6) Chaconne (Acte I, sc.7) – instrumental Distribution Jonathan Cohen, chef associé, direction