Mapping Mobility 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15Th Elia Biennial Conference Rotterdam 2018 Urbanism Education

Programme 21-24 NOVEMBER 2018 15TH ELIA ART BIENNIAL CONFERENCE EDUCATION ROTTERDAM URBANISM 2018 WELCOME 3 - 5 3 DOWNLOAD THE WHOVA APP Welcome to the 15th ELIA Biennial Conference Welcome to Rotterdam 5 ROTTERDAM & VENUES 6 -11 AND JOIN THE 15TH ELIA The city of Rotterdam 6 Main conference venue: De Doelen 7 BIENNIAL CONFERENCE Maassilo 8 Blue City 8 Walhalla / Circus Rotjeknor / Codarts Circus Arts 8 WORM / TENT 8 Other venues 9 Map of Rotterdam 10 EVENT TIMETABLE 12 - 18 PLENARY SESSIONS 20 - 21 PANEL SESSION 22 - 25 MOBILE THEMATIC SESSIONS THURSDAY 22 NOVEMBER 26 - 33 MOBILE THEMATIC SESSIONS FRIDAY 23 NOVEMBER 34 - 41 MEMBERS’ EVENTS 42 - 47 Open Space 43 ELIA Afternoon 44 General Assembly 47 CULTURAL PROGRAMME 48 - 51 Institution tours 48 Exhibition Maaskant Award: alumni of Willem de Kooning Academy 50 Performance 50 Civic Reception 51 Closing Party 51 SPEAKERS BIOGRAPHIES 52 - 55 Berhanu Ashagrie 52 Maria Balshaw 53 Elizabeth Giorgis 54 Jeanette Winterson 55 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 57 Info point, internet, useful numbers 57 THE EVENT INVITATION CODE IS: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 58 - 59 ELIABIEN18 NOTES 60 - 67 WELCOME BY THE STEERING GROUP WELCOME TO THE 15TH ELIA BIENNIAL CONFERENCE RESILIENCE AND THE CITY: ART, EDUCATION, URBANISM The contrast between the famously elegant renaissance city of Florence in the heart of Italy where the previous ELIA Biennial Conference took place two years ago, and the reconstructed industrial, cultural and commercial city of Rotterdam could hardly be more extreme. Situated just half an hour away from the more famous capital city, Rotterdam’s gritty determination and confdence in confronting economic, social and cultural opportunities and challenges make it an ideal location for this year’s conference. -

Leren Excelleren

Leren excelleren Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO: een overzicht Leren excelleren Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO: een overzicht Resultaten van de landelijke inventarisatie 2009-2010 Marca Wolfensberger Hanzehogeschool Groningen Nelleke de Jong Universiteit Utrecht Lyndsay Drayer Hanzehogeschool Groningen Hanzehogeschool Groningen Universiteit Utrecht 2012 Dit onderzoek is uitgevoerd vanuit het Lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving van de Hanzehogeschool Groningen. Het onderzoek is gedaan in opdracht van en mede moge- lijk gemaakt door de HBO-raad en is een samenwerking tussen de Universiteit Utrecht en de Hanzehogeschool Groningen. Met bijdragen van: Elize Eichler, student Windesheim Honours College, specialisatie Communication & Media, Christelijke Hogeschool Windesheim Rob Flohr MSc MA, docent statistiek, wiskunde en wetenschapfilosofie, Stenden Hogeschool Pola Hirschmann, student Technische Commerciële Textielkunde, Saxion Hogeschool Sander Kleinpenning, student HBO-V, Hogeschool van Arnhem en Nijmegen Pieter Veenstra, projectleider Hanze Sirius Programma, Hanzehogeschool Groningen Petra Wisselink, student Voeding & Diëtiek, Hanzehogeschool Groningen Voor meer informatie [email protected] Cartografie en Vormgeving Universiteit Utrecht - Faculteit Geowetenschappen - C&M (Carto-)grafische Vormgeving 8173 © Lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving, 2012 Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets van deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand of openbaar -

KLIKKEN OP NEDERLAND 2015 Internetführer Zum Studium in Den Niederlanden

KLIKKEN OP NEDERLAND 2015 Internetführer zum Studium in den Niederlanden Herausgegeben von: Euregio Rhein- Waal Emmericher Straße 24 47533 Kleve Tel. 0049- (0)2821- 793-00 Fax. 0049- (0)2821-793-030 e-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.euregio.org Euregio rhein- maas- nord Konrad- Zuse- Ring 6 41179 Mönchengladbach Tel. 0049- (0) 2161-69850 e-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.euregio-rmn.de Diese Online- Broschüre ist mit finanzieller Hilfe von EURES (EURopean Employment Services ), einer Initiative der Europäischen Kommission zur Förderung der Arbeitsmobilität innerhalb der Europäischen Union, entstanden. Verfasser: Diplom- Volkswirt Robert Marzell und Diplom- Verwaltungswirtin Barbara Marzell Redaktionsschluss: Juni 2015 Kleve, Juni 2015 Copyright: Euregio Rhein- Waal & euregio rhein-maas-nord und Robert Marzell 1 KLIKKEN OP NEDERLAND 2015 Der Internetführer zum Thema Studium in den Niederlanden Inhalt: 1) Einleitung 2) Das niederländische Hochschulwesen und seine Institutionen 2a)Darstellungen des niederländischen Hochschulwesens 2b)Institutionen im Hochschulbereich 3) Suchmöglichkeiten zu niederländischen Studiengängen, -orten und Hochschulen 3a)Suchmaschinen und Datenbanken zu niederländischen Studiengängen und Studienorten 3b)Listen mit allen Hochschulen der Niederlande 3c)Kooperationen von deutschen und niederländischen Hochschulen 3d)Deutschsprachige Websites niederländischer Hochschulen zu ihrem Studienangebot und den Studienbedingungen Stand 2015 4) Webseiten von Deutsche erfahrungsgemäß interessierenden Studiengängen -

Van Vwo Naar

Van profiel naar studie Aanvullende eisen Bekijk welke profielen toegang geven tot welke A8 met Wiskunde A of Wiskunde B studie. Voor sommige opleidingen zijn er naast het B2 met (Bedrijfseconomie of Economie of M&O profiel aanvullende vakken nodig. Ook dit is terug te B6 met Bedrijfseconomie of Economie of M&O vinden. Het overzicht is altijd up-to-date en het B7 met Bedrijfseconomie of Economie of Maatschappijwetenschappen of M&O schema is eenvoudig op te slaan als pdf (om B8 met Biologie digitaal te gebruiken of te printen). Het overzicht is B10 met Biologie en Scheikunde per studierichting op te slaan (bijv. Techniek) of alle B12 met Biologie of Natuur, leven en technologie studierichtingen in één keer. B15 met Wiskunde B en (Bedrijfseconomie of Economie of M&O) E2 met Economie Hoe werkt het schema? E3 met Economie en (Wiskunde A of Wiskunde B) E5 met Economie of M&O of Bedrijfseconomie In de eerste kolom staan de studies die kunnen E6 met Economie of Wiskunde A of Wiskunde B worden gevolgd. De tweede kolom geeft per profiel aan of wel/geen toegang mogelijk is tot de studie of N1 met Natuur, leven en technologie of Natuurkunde dat er een aanvullende eis is. Deze aanvullende eis N2 met Natuur, leven en technologie of Scheikunde wordt aangegeven met een code (letter + cijfer). In N3 met Natuurkunde de laatste kolom staan de instellingen N9 met Natuurkunde en Wiskunde B (hogescholen en universiteiten) waar de opleiding N12 met Natuurkunde of Natuur, leven en technologie wordt aangeboden. S1 met Scheikunde S5 met Scheikunde en Wiskunde A Disclaimer V2 met tweede moderne vreemde taal De data in de online tool Van profiel naar studie wordt continu ververst en is daarmee altijd actueel. -

Centros De Educacion Universitaria (Wo) Que Imparten Español

CENTROS DE EDUCACION UNIVERSITARIA (WO) QUE IMPARTEN ESPAÑOL Provincia - BRABANTE SEPTENTRIONAL 1. Universiteit Tilburg, Language Center Warandelaan 2 5037 AB Tilburg 013 - 4669111 [email protected] www.tilburguniversity.edu Provincia - GRONINGA 1. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen 2. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Talencentrum Oude Kijk in 't Jatstraat 26 Oude Kijk in 't Jatstraat 26 9712 EK Groningen 9712 EK Groningen 050 - 3639111 050 - 3635802 [email protected] [email protected] www.rug.nl www.rug.nl Provincia - GÜELDRES 1. Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen 2. Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, Instituut voor Leraar en School Erasmusplein 1 Erasmusplein 1 6525 HT Nijmegen 6525 HT Nijmegen 024 - 3616161 024 - 3615572 [email protected] [email protected] www.ru.nl/ciw-bc www.ru.nl/ils 4. Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, 5. Wageningen University, Wageningen Radboud In'to Languages In'to Languages Erasmusplein 1 Droevendaalsesteeg 2 6525 HT Nijmegen 6708 PB Wageningen 024 - 3612159 031 - 7482552 [email protected] [email protected] www.ru.nl/radboudintolanguages www.wageningenur.nl/into Provincia - HOLANDA MERIDIONAL 1. Technische Universiteit Delft, ITAV 2. Leiden Univeristy College The Hague Jaffalaan 5 Anna van Buerenplein 301 2628 BX Delft 2595 DG Den Haag 015 - 2783646 070 - 8009503 [email protected] [email protected] www.tc.tbm.tudelft.nl www.lucthehague.nl 3. Universiteit Leiden 4. Universiteit Leiden- ICLON Lange Voorhout 44 Wassenaarseweg 62A 2514 EG Den Haag 2333 AL Leiden 071 - 5272727 071 - 5274015 [email protected] [email protected] www.leidenuniv.nl www.iclon.leidenuniv.nl 5. Universiteit Leiden, Academisch 6. Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, Talencentrum Taal & Traningscentrum Cleveringaplaats 1 Burgemeester Oudlaan 50 2311 BD Leiden 3062 PA Rotterdam 071 - 5272332 010 - 4081995 [email protected] [email protected] www.hum.leidenuniv.nl/talencentrum www.eur.nl/ttc Provincia - HOLANDA SEPTENTRIONAL 1. -

Incoming Degree Student Mobility in Dutch Higher Education 2018-2019

Incoming degree student mobility in Dutch higher education 2018-2019 Incoming degree student mobility in Dutch higher education 2018-2019 www.nuffic.nl/facts-and-figures 2 INCOMING DEGREE STUDENT MOBILITY IN DUTCH HIGHER EDUCATION 2018-2019 Summary . In 2018-2019, there were 85,955 international degree students and 14,344 homecoming students enrolled in Dutch public higher education. In 2018-2019, the share of international students in Dutch public higher education increased to 11.5% of all students, compared to 10.5% in the previous year. More students from countries outside the European Economic Area (EEA) come to the Netherlands. Over a two-year period, the share of non-EEA students among international students increased from 24.8% in 2016-2017, to 26.9% in 2018-2019. In 2018-19, international students represented a total of 170 different nationalities. The absolute number of international students grew the most for bachelor’s programmes in research universities (RU). In 2017-2018, international students made up 17.8% of the new enrolments in these programmes, increasing to 20.4% in 2018-2019. This growth makes 2018-2019 the first academic year with more international degree students in bachelor’s programmes at research universities (30,500) than at universities of applied sciences (27,186). For master’s programmes, however, the shares of international students are still much higher. Research universities have 25,669 international master’s students enrolled, or 23.6% of all their master’s students, while universities of applied sciences (UAS) master’s programmes have 2,145 international students who make up 20.5% of all UAS master’s students. -

Study in Holland: Open to International Minds (EU)

Nicosia Study in Holland Open to international minds School, Grammar Date October 2020 Name GS Higher Education Advisory Team TheTitle Holland from a student’s viewpoint... Nicosia School, Grammar TheStudy in Holland – Open to international minds It’s on your calendar! Sign up today.Nicosia https://www.ubivent.com/register/11/Virtually_Orange School, Grammar The Why Study in Holland? Nicosia School, Grammar The Dutch Higher Education Research Universities: Academic study and research Vary in size from 6,000-30,000 students Nicosia Bachelor of Arts (BA) & Bachelor of Science (BSc): 3 years Universities of Applied Sciences: Practical application of knowledge Vary in size from 20,000-40,000 students Bachelor of Arts (BA) & Bachelor of Science (BSc): 4 yearsSchool, Institutes for International Education Focus on development oriented courses in small, intercultural groups What is the difference?Grammar https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LrwFqNYybfM RANKING: • https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/best-universities-netherlands TheStudy in Holland – Open to international minds Research Universities with International options • Delft University of Technology • Eindhoven University of Technology • University of Humanistic Studies • Erasmus University Rotterdam • University of Twente Nicosia • Leiden University • Utrecht University • Maastricht University • VU Amsterdam • Nyenrode Business Universiteit • Wageningen University and Research Centre • Open University School, • Radboud University Nijmegen • https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZ7LqWFgTh3hG -

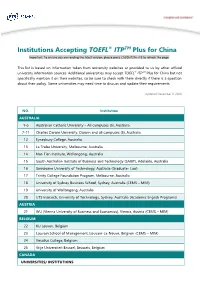

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: to Ensure You Are Reading the Latest Version, Please Press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to Refresh the Page

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: To ensure you are reading the latest version, please press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to refresh the page. This list is based on information taken from university websites or provided to us by other official university information sources. Additional universities may accept TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China but not specifically mention it on their websites, so be sure to check with them directly if there is a question about their policy. Some universities may need time to discuss and update their requirements. Updated December 9, 2020 NO. Institution AUSTRALIA 1-6 Australian Catholic University – All campuses (6), Australia 7-11 Charles Darwin University, Darwin and all campuses (5), Australia 12 Eynesbury College, Australia 13 La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia 14 Nan Tien Institute, Wollongong, Australia 15 South Australian Institute of Business and Technology (SAIBT), Adelaide, Australia 16 Swinburne University of Technology, Australia (Graduate- Law) 17 Trinity College Foundation Program, Melbourne, Australia 18 University of Sydney Business School, Sydney, Australia (CEMS – MIM) 19 University of Wollongong, Australia 20 UTS Insearch, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia (Academic English Programs) AUSTRIA 21 WU (Vienna University of Business and Economics), Vienna, Austria (CEMS – MIM) BELGIUM 22 KU Leuven, Belgium 23 Louvain School of Management, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium (CEMS – MIM) 24 Vesalius College, Belgium 25 Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium CANADA UNIVERSITIES/ -

Authentieke Versie (PDF)

Nr. 13799 27 juli STAATSCOURANT 2011 Officiële uitgave van het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden sinds 1814. Regeling van de Staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap van 10 juli 2011, nr. HO&S/CBV/268961, tot wijziging van de Regeling financiën hoger onderwijs De Staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, Handelende in overeenstemming met de Minister van Economische Zaken, Landbouw, en Innovatie; Gelet op de artikelen 4.11, 4.23, 4.24, 4.25, vierde lid, en 4.27, eerste lid, onderdeel d, van het Uitvoe- ringsbesluit WHW 2008; Besluit: ARTIKEL I WIJZIGING VAN DE REGELING FINANCIËN HOGER ONDERWIJS PER 1 JANUARI 2011 De Regeling financiën hoger onderwijs wordt als volgt gewijzigd: A Artikel 4, vierde lid, komt te luiden: 4. Het bedrag, bedoeld in artikel 4.21, eerste lid, van het besluit is € 93.408,00. B Artikel 4, vijfde lid, komt te luiden: 5. Het bedrag, bedoeld in artikel 4.21, tweede lid, van het besluit is € 77.840,00. C Artikel 5 komt als volgt te luiden: Artikel 5. Rentepercentage Het rentepercentage bedoeld in artikel 4.25, vierde lid, van het besluit voor investeringen is voor: 1°. de begrotingsjaren 2001 en 2011 3,75 procent, 2°. de begrotingsjaren 1992 en 2002 5,00 procent, 3°. de begrotingsjaren 1993 en 2003 4,00 procent, 4°. de begrotingsjaren 1994 en 2004 4,25 procent, 5°. de begrotingsjaren 1995 en 2005 3,5 procent, 6°. de begrotingsjaren 1996 en 2006 3,75 procent, 7°. de begrotingsjaren 1997 en 2007 4,25 procent, 8°. in de begrotingsjaren 1998 en 2008 4,5 procent, 9°. -

ASSESSMENT REPORT Limited Programme Assessment

ASSESSMENT REPORT Limited programme assessment Professional Bachelor programme Circus and Performance Art Fulltime Fontys Academy of Circus and Performance Art (ACAPA) Lange Voorhout 14 2514 ED The Hague T) ++ 31 70 30 66 800 F) ++31 70 30 66 870 I www.hobeon.nl E [email protected] ASSESSMENT REPORT Limited programme assessment Bachelor programme Circus and Performance Art Fulltime Fontys Academy of Circus and Performance Art (ACAPA) Croho registration: 30014 Hobéon Certificering BV Dated: 12 October 2018 Audit Committee Drs. W.G. van Raaijen, chair T.A. Roberts MSc S. Flor D. Westera, student member Secretary / co-ordinator: H.R. van der Made CONTENTS 1. GENERAL AND QUANTITATIVE DATA 1 2. SUMMARY 3 3. INTRODUCTION 5 4. FINDINGS AND JUDGEMENTS 7 4.1. Intended learning outcomes 7 4.2. Teaching and Learning Environment 9 4.3. Student Assessment 14 4.4. Achieved Learning Outcomes 17 5. OVERALL CONCLUSION 19 6. RECOMMENDATIONS 21 ANNEXES 23 ANNEX I Overview of judgements 25 ANNEX II Programme of site-visit 27 ANNEX III Documents reviewed 29 ANNEX IV Composition of the audit panel 31 ©Hobéon Certificering | Assessment Report Limited Assessment of the Bachelor Circus and Performance Art, Fontys ACAPA | v2.0 | 0 1. GENERAL AND QUANTITATIVE DATA General data Institution Name Fontys Academy of Circus & Performance Art (ACAPA) Status Government funded Outcomes of Institutional Quality Assessment Pass Programme Name of programme in Central Register of Higher Circus and Performance Art Professional Education (CROHO) ISAT-code CROHO 30014 Orientation and level Professional Bachelor Number of credits 240EC Variant Fulltime Specialisations n.a. Language of instruction English Location Tilburg Special Quality Feature n.a. -

Journal of the European Honors Council

Journal of the European Honors Council The Journal of the European Honors Council aims to share research A results, knowledge and good practices related to talent development and honors programs in higher education. C It is published by the European Honors Council (EHC): a council for all involved in talent development in higher education in Europe. Honors I This is the fifrth issue in total of the Journal of the European Honors Council (JEHC). The JEHC is proudly published in open access under a Excellence CC-BY license. V x E p M l E o N eu r ope T eVolume 3 (2019), no. 2 EHC no. 2 3 (2019), Council – Volume Journalof the Honors European European Honors Council ISSN 2543-2311 www.jehc.eu Volume 3 No. 2 2019 Journal of the European Honors Council The aim of the Journal of the European Honors Council is to share research results, knowledge and good practices related to talent development and honors programs in higher education. Editorial Board The Editorial Board of this issue consists of (in alphabetical order): • Drs. Pierre van Eijl, Utrecht University, the Netherlands • Dr. Marleen Eyckmans, University of Antwerp, Belgium • Dr. Maarten Hogenstijn, Hanze University of Applied Sciences Groningen, the Netherlands; European Honors Council Secretary (coordinating editor) • Prof. Dr. Beata Jones, Texas Christian University, USA • Drs. Tineke Kingma, Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, the Netherlands • Prof. Dr. Albert Pilot, Utrecht University, the Netherlands • Dr. David Rott, University of Münster, Germany • Dr. Lineke Stobbe, Windesheim University of Applied Sciences, the Netherlands • Dr. Marca Wolfensberger, Hanze University of Applied Sciences Groningen and Utrecht University, the Netherlands; European Honors Council President During the publication process of this issue, Dr. -

Excellentieprogramma's in Het HBO in Nederland

Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO in Nederland Voorpublicatie van de landelijke inventarisatie 2009-2010 Marca Wolfensberger & Nelleke de Jong Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO in Nederland Voorpublicatie van de landelijke inventarisatie 2009-2010 Marca Wolfensberger & Nelleke de Jong Dit onderzoek is een samenwerking tussen de Universiteit Utrecht en de Hanzehogeschool Groningen en valt onder auspiciën van het lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving van de Hanzehogeschool Groningen. 2010 Lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving Colofon Dit onderzoek is een samenwerking tussen de Universiteit Utrecht en de Hanzehogeschool Groningen en valt onder auspiciën van het lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving van de Hanzehogeschool Groningen. Meer achtergrondinformatie over het onderzoek kunt u verkrijgen bij: Marca Wolfensberger E: [email protected] © Lectoraat Excellentie in Hoger Onderwijs en Samenleving, 2010 Titel: Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO in Nederland Subtitel: Voorpublicatie van de landelijke inventarisatie 2009-2010 Auteurs: Marca Wolfensberger & Nelleke de Jong Ontwerp omslag: Poppie Art Kaarten: Margot Stoete, Geomedia Lay out: Poppie Art Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets van deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij electronisch, mechanisch, door fotokopieën, opnamen of enige andere manier, zonder schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Inhoud Inleiding 6 Onderzoeksopzet en methoden 8 Uitkomsten 10 Aantal programma’s en instellingen 10 Aantal studenten 12 Honorering 12 Slot 14 Bronnen 16 Excellentieprogramma’s in het HBO in Nederland Inleiding Dit is een voorpublicatie van het volledige rapport over de inventarisatie van excellentieprogramma’s in 2009-2010. In deze voorpublicatie zal alleen worden ingegaan op het aantal programma’s en het aantal studenten.