ICT in Schools 2008–11 an Evaluation of Information and Communication Technology Education in Schools in England 2008–11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: a Lesson from Summerhill? Author(S): John Darling Source: Oxford Review of Education, Vol

A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: A Lesson from Summerhill? Author(s): John Darling Source: Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1992), pp. 45-57 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1050383 Accessed: 23-05-2017 13:11 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Oxford Review of Education This content downloaded from 200.130.19.195 on Tue, 23 May 2017 13:11:38 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992 45 A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: a lesson from Simmerhill? JOHN DARLING ABSTRACT Neill's philosophy of individual freedom has attracted world-wide attention, but there has been little discussion of its practical converse-individual responsibility and collective authority. Renouncing the powers normally invested in a headmaster, Neill instituted a system of community-based decision-making. This article explains the reasoning behind this arrangement and asks whether it made school life truly democratic. Mainstream education shows no interest in such matters. Democratisation is not seen as the kind of progressive reform which can be incorporated into a system of schooling where curricula are imposed and pupils are supposed to be kept under control. -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Open PDF 715KB

LBP0018 Written evidence submitted by The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium Education Select Committee Left behind white pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds Inquiry SUBMISSION FROM THE NORTHERN POWERHOUSE EDUCATION CONSORTIUM Introduction and summary of recommendations Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium are a group of organisations with focus on education and disadvantage campaigning in the North of England, including SHINE, Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) and Tutor Trust. This is a joint submission to the inquiry, acting together as ‘The Northern Powerhouse Education Consortium’. We make the case that ethnicity is a major factor in the long term disadvantage gap, in particular white working class girls and boys. These issues are highly concentrated in left behind towns and the most deprived communities across the North of England. In the submission, we recommend strong actions for Government in particular: o New smart Opportunity Areas across the North of England. o An Emergency Pupil Premium distribution arrangement for 2020-21, including reform to better tackle long-term disadvantage. o A Catch-up Premium for the return to school. o Support to Northern Universities to provide additional temporary capacity for tutoring, including a key role for recent graduates and students to take part in accredited training. About the Organisations in our consortium SHINE (Support and Help IN Education) are a charity based in Leeds that help to raise the attainment of disadvantaged children across the Northern Powerhouse. Trustees include Lord Jim O’Neill, also a co-founder of SHINE, and Raksha Pattni. The Northern Powerhouse Partnership’s Education Committee works as part of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership (NPP) focusing on the Education and Skills agenda in the North of England. -

Undergraduate Admissions by

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2019 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 6 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 14 3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 18 4 3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 20 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 25 6 5 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 3 3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 17 10 6 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent 3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 10 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 38 14 12 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10050 Desborough College SL6 2QB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10051 Newlands Girls' School SL6 5JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent 3 <3 -

REGISTER of STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021

REGISTER OF STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under the Student route of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each route (Student and/or Child Student) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about the Student route of the points-based system, please refer to the guidance for sponsors in the Student route on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under the Student route: 1,130 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Route Immigration Locations Compliance Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abercorn School London Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Aberdour School Educational Trust Tadworth Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abertay University -

Secondaryschoolspendinganaly

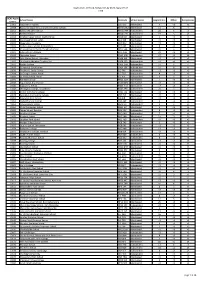

www.tutor2u.net Analysis of Resources Spend by School Total Spending Per Pupil Learning Learning ICT Learning Resources (not ICT Learning Resources (not School Resources ICT) Total Resources ICT) Total Pupils (FTE) £000 £000 £000 £/pupil £/pupil £/pupil 000 Swanlea School 651 482 1,133 £599.2 £443.9 £1,043.1 1,086 Staunton Community Sports College 234 192 426 £478.3 £393.6 £871.9 489 The Skinners' Company's School for Girls 143 324 468 £465.0 £1,053.5 £1,518.6 308 The Charter School 482 462 944 £444.6 £425.6 £870.2 1,085 PEMBEC High School 135 341 476 £441.8 £1,117.6 £1,559.4 305 Cumberland School 578 611 1,189 £430.9 £455.1 £885.9 1,342 St John Bosco Arts College 434 230 664 £420.0 £222.2 £642.2 1,034 Deansfield Community School, Specialists In Media Arts 258 430 688 £395.9 £660.4 £1,056.4 651 South Shields Community School 285 253 538 £361.9 £321.7 £683.6 787 Babington Community Technology College 268 290 558 £350.2 £378.9 £729.1 765 Queensbridge School 225 225 450 £344.3 £343.9 £688.2 654 Pent Valley Technology College 452 285 737 £339.2 £214.1 £553.3 1,332 Kemnal Technology College 366 110 477 £330.4 £99.6 £430.0 1,109 The Maplesden Noakes School 337 173 510 £326.5 £167.8 £494.3 1,032 The Folkestone School for Girls 325 309 635 £310.9 £295.4 £606.3 1,047 Abbot Beyne School 260 134 394 £305.9 £157.6 £463.6 851 South Bromsgrove Community High School 403 245 649 £303.8 £184.9 £488.8 1,327 George Green's School 338 757 1,096 £299.7 £670.7 £970.4 1,129 King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys 211 309 520 £297.0 £435.7 £732.7 709 Joseph -

Summerhill Is the Most Unusual School in the World. Here's a Place Where

Summerhill is the most unusual school in the world. Here’s a place where children are not compelled to go to class – they can stay away from lessons for years, if they want to. Yet, strangely enough, the boys and girls in this school LEARN! In fact, being deprived of lessons turns out to be a severe punishment. Summerhill has been run by A. S . Neill for almost forty years. This is the world’s greatest experiment in bestowing unstinted love and approval on children. This is the place, where one courageous man, backed by courageous parents, has had the fortitude to actually apply – without reservation – the principles of freedom and non- repression. The school runs under a true children’s government where the “bosses” are the children themselves. Despite the common belief that such an atmosphere would create a gang of unbridled brats, visitors to Summerhill are struck by the self-imposed discipline of the pupils, by their joyousness, the good manners. These kids exhibit a warmth and lack of suspicion toward adults, which is the wonder, and delight of even official British school investigators. In this book A. S. Neill candidly expresses his unique - and radical – opinions on the important aspects of parenthood and child rearing. These strong commendations of authors and educators attest that every parent who reads this book will find in it many examples of how Neill’s philosophy may be applied to daily life situations. Educators will find Neill’s refreshing viewpoints practical and inspiring. Reading this book is an exceptionally gratifying experience, for it puts into words the deepest feelings of all who care about children, and wish to help them lead happy, fruitful lives. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

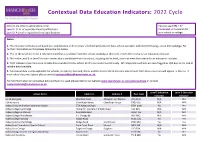

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Academy Name LA Area Parliamentary Constituency St

Academy Name LA area Parliamentary Constituency St Joseph's Catholic Primary School Hampshire Aldershot Aldridge School - A Science College Walsall Aldridge-Brownhills Shire Oak Academy Walsall Aldridge-Brownhills Altrincham College of Arts Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Altrincham Grammar School for Boys Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Ashton-on-Mersey School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Elmridge Primary School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Loreto Grammar School Trafford Altrincham and Sale West Heanor Gate Science College Derbyshire Amber Valley Kirkby College Nottinghamshire Ashfield Homewood School and Sixth Form Centre Kent Ashford The Norton Knatchbull School Kent Ashford Towers School and Sixth Form Centre Kent Ashford Fairfield High School for Girls Tameside Ashton-under-Lyne Aylesbury High School Buckinghamshire Aylesbury Sir Henry Floyd Grammar School Buckinghamshire Aylesbury Dashwood Primary Academy Oxfordshire Banbury Royston Parkside Primary School Barnsley Barnsley Central All Saints Academy Darfield Barnsley Barnsley East Oakhill Primary School Barnsley Barnsley East Upperwood Academy Barnsley Barnsley East The Billericay School Essex Basildon and Billericay Dove House School Hampshire Basingstoke The Costello School Hampshire Basingstoke Hayesfield Girls School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Oldfield School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Ralph Allen School Bath and North East Somerset Bath Batley Girls' High School - Visual Arts College Kirklees Batley and Spen Batley Grammar School Kirklees Batley -

Summerhill School

Revista HISTEDBR On-line Artigo SUMMERHILL SCHOOL Zoë Neill Readhead i Andréa Villela Mafra da Silva ii Nobody connected with children can claim. To know the true nature of childhood. If they have not heard about A.S. Neill’s Summerhill School. You may love the idea, or hate it. But if you have your own children, Have taught children, or have ever been a child. One thing is for sure, you will never view childhood or education in the same way agem . Zoë Neill Readhead ABSTRACT: Summerhill School was founded in 1921 at a time when the rights of individuals were less respected than they are today. Children were beaten in most homes at some time or another and discipline was the key work in child rearing. Through its self-government and freedom it has struggled for more than eighty years against pressures to conform, in order to give children the right to decide for themselves. The school is now a thriving democratic community, showing that children learn to be self-confident, tolerant and considerate when they are given space to be themselves. Summerhill School is one of the most famous schools in the world, and has influenced educational practice in many schools and universities. The democratic schools movement is now blossoming internationally, with many schools far and wide being based upon the philosophy of A. S. Neill or inspired by reading his books. Summerhill is a community of over a hundred people. About 95 of these are children aged between 5 and 18. The rest are teachers, house parents and other staff. -

Summerhill School

No. 25 October 2018 How excited are we all about the upcoming One Hundred Years of Summerhill? SO excited! 2021 will be a year of local, national and international celebration of A.S. Neill’s educational philosophy and one hundred years of Summerhill School. What an achievement! That daydreamer of a Scotsman with his crazy ideas about education, reviled by the popular press, misunderstood and misrepresented at every turn, this little ‘experiment’ now comes of age to truly show that freedom for children works and to bring to the 21st century many important lessons about education and emotional growth. It could not come to the fore at a better time in history. So, this will be an opportunity for all of us to celebrate the inspirations A.S. Neill gave us as a child, parent, student, teacher, educator, school, university or business. First of all, we are kicking off the celebrations with a residential weekend at Summerhill in August 2019. The Summerhill Experience For the first time ever, we are inviting people to spend a weekend with us and really learn how Summerhill works – How do we do Safeguarding Children? How do we prepare for school inspections? What exams do we offer? How do our teachers approach their roles? How do the pupils feel about their own roles and lives in the school and afterwards? It will include A.S. Neill’s founding principles, the famous Self-Government Meetings, policies, paperwork, teaching and a chance to talk to adults and pupils. It is also a chance to just hang out in this unique historic environment and chill! Profits will go to the building of the new A.S.