Reception of Arthur Sutherland Neill's Pedagogical Concept and His

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: a Lesson from Summerhill? Author(S): John Darling Source: Oxford Review of Education, Vol

A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: A Lesson from Summerhill? Author(s): John Darling Source: Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1992), pp. 45-57 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1050383 Accessed: 23-05-2017 13:11 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Taylor & Francis, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Oxford Review of Education This content downloaded from 200.130.19.195 on Tue, 23 May 2017 13:11:38 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Oxford Review of Education, Vol. 18, No. 1, 1992 45 A. S. Neill on Democratic Authority: a lesson from Simmerhill? JOHN DARLING ABSTRACT Neill's philosophy of individual freedom has attracted world-wide attention, but there has been little discussion of its practical converse-individual responsibility and collective authority. Renouncing the powers normally invested in a headmaster, Neill instituted a system of community-based decision-making. This article explains the reasoning behind this arrangement and asks whether it made school life truly democratic. Mainstream education shows no interest in such matters. Democratisation is not seen as the kind of progressive reform which can be incorporated into a system of schooling where curricula are imposed and pupils are supposed to be kept under control. -

REGISTER of STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021

REGISTER OF STUDENT SPONSORS Date: 27-January-2021 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under the Student route of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each route (Student and/or Child Student) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about the Student route of the points-based system, please refer to the guidance for sponsors in the Student route on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under the Student route: 1,130 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Route Immigration Locations Compliance Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Abercorn School London Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Student Sponsor Student Aberdour School Educational Trust Tadworth Independent school Student Sponsor Child Student Abertay University -

Secondaryschoolspendinganaly

www.tutor2u.net Analysis of Resources Spend by School Total Spending Per Pupil Learning Learning ICT Learning Resources (not ICT Learning Resources (not School Resources ICT) Total Resources ICT) Total Pupils (FTE) £000 £000 £000 £/pupil £/pupil £/pupil 000 Swanlea School 651 482 1,133 £599.2 £443.9 £1,043.1 1,086 Staunton Community Sports College 234 192 426 £478.3 £393.6 £871.9 489 The Skinners' Company's School for Girls 143 324 468 £465.0 £1,053.5 £1,518.6 308 The Charter School 482 462 944 £444.6 £425.6 £870.2 1,085 PEMBEC High School 135 341 476 £441.8 £1,117.6 £1,559.4 305 Cumberland School 578 611 1,189 £430.9 £455.1 £885.9 1,342 St John Bosco Arts College 434 230 664 £420.0 £222.2 £642.2 1,034 Deansfield Community School, Specialists In Media Arts 258 430 688 £395.9 £660.4 £1,056.4 651 South Shields Community School 285 253 538 £361.9 £321.7 £683.6 787 Babington Community Technology College 268 290 558 £350.2 £378.9 £729.1 765 Queensbridge School 225 225 450 £344.3 £343.9 £688.2 654 Pent Valley Technology College 452 285 737 £339.2 £214.1 £553.3 1,332 Kemnal Technology College 366 110 477 £330.4 £99.6 £430.0 1,109 The Maplesden Noakes School 337 173 510 £326.5 £167.8 £494.3 1,032 The Folkestone School for Girls 325 309 635 £310.9 £295.4 £606.3 1,047 Abbot Beyne School 260 134 394 £305.9 £157.6 £463.6 851 South Bromsgrove Community High School 403 245 649 £303.8 £184.9 £488.8 1,327 George Green's School 338 757 1,096 £299.7 £670.7 £970.4 1,129 King Edward VI Camp Hill School for Boys 211 309 520 £297.0 £435.7 £732.7 709 Joseph -

Summerhill Is the Most Unusual School in the World. Here's a Place Where

Summerhill is the most unusual school in the world. Here’s a place where children are not compelled to go to class – they can stay away from lessons for years, if they want to. Yet, strangely enough, the boys and girls in this school LEARN! In fact, being deprived of lessons turns out to be a severe punishment. Summerhill has been run by A. S . Neill for almost forty years. This is the world’s greatest experiment in bestowing unstinted love and approval on children. This is the place, where one courageous man, backed by courageous parents, has had the fortitude to actually apply – without reservation – the principles of freedom and non- repression. The school runs under a true children’s government where the “bosses” are the children themselves. Despite the common belief that such an atmosphere would create a gang of unbridled brats, visitors to Summerhill are struck by the self-imposed discipline of the pupils, by their joyousness, the good manners. These kids exhibit a warmth and lack of suspicion toward adults, which is the wonder, and delight of even official British school investigators. In this book A. S. Neill candidly expresses his unique - and radical – opinions on the important aspects of parenthood and child rearing. These strong commendations of authors and educators attest that every parent who reads this book will find in it many examples of how Neill’s philosophy may be applied to daily life situations. Educators will find Neill’s refreshing viewpoints practical and inspiring. Reading this book is an exceptionally gratifying experience, for it puts into words the deepest feelings of all who care about children, and wish to help them lead happy, fruitful lives. -

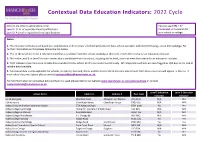

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

ICT in Schools 2008–11 an Evaluation of Information and Communication Technology Education in Schools in England 2008–11

ICT in schools 2008–11 An evaluation of information and communication technology education in schools in England 2008–11 Since the Education Reform Act of 1988, information and communication technology has been compulsory for all pupils from 5 to 16 in maintained schools. This report draws on evidence from the inspection of information and communication technology in primary, secondary and special schools between 2008 and 2011. The use of ICT is considered as both a specialist subject and across the wider school curriculum. Age group: 5–16 Published: December 2011 Reference no: 110134 The Office for Standards in Education, Children's Services and Skills (Ofsted) regulates and inspects to achieve excellence in the care of children and young people, and in education and skills for learners of all ages. It regulates and inspects childcare and children's social care, and inspects the Children and Family Court Advisory Support Service (Cafcass), schools, colleges, initial teacher training, work-based learning and skills training, adult and community learning, and education and training in prisons and other secure establishments. It assesses council children’s services, and inspects services for looked after children, safeguarding and child protection. If you would like a copy of this document in a different format, such as large print or Braille, please telephone 0300 123 1231, or email [email protected]. You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/, write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected]. -

Summerhill School

Revista HISTEDBR On-line Artigo SUMMERHILL SCHOOL Zoë Neill Readhead i Andréa Villela Mafra da Silva ii Nobody connected with children can claim. To know the true nature of childhood. If they have not heard about A.S. Neill’s Summerhill School. You may love the idea, or hate it. But if you have your own children, Have taught children, or have ever been a child. One thing is for sure, you will never view childhood or education in the same way agem . Zoë Neill Readhead ABSTRACT: Summerhill School was founded in 1921 at a time when the rights of individuals were less respected than they are today. Children were beaten in most homes at some time or another and discipline was the key work in child rearing. Through its self-government and freedom it has struggled for more than eighty years against pressures to conform, in order to give children the right to decide for themselves. The school is now a thriving democratic community, showing that children learn to be self-confident, tolerant and considerate when they are given space to be themselves. Summerhill School is one of the most famous schools in the world, and has influenced educational practice in many schools and universities. The democratic schools movement is now blossoming internationally, with many schools far and wide being based upon the philosophy of A. S. Neill or inspired by reading his books. Summerhill is a community of over a hundred people. About 95 of these are children aged between 5 and 18. The rest are teachers, house parents and other staff. -

Summerhill School

No. 25 October 2018 How excited are we all about the upcoming One Hundred Years of Summerhill? SO excited! 2021 will be a year of local, national and international celebration of A.S. Neill’s educational philosophy and one hundred years of Summerhill School. What an achievement! That daydreamer of a Scotsman with his crazy ideas about education, reviled by the popular press, misunderstood and misrepresented at every turn, this little ‘experiment’ now comes of age to truly show that freedom for children works and to bring to the 21st century many important lessons about education and emotional growth. It could not come to the fore at a better time in history. So, this will be an opportunity for all of us to celebrate the inspirations A.S. Neill gave us as a child, parent, student, teacher, educator, school, university or business. First of all, we are kicking off the celebrations with a residential weekend at Summerhill in August 2019. The Summerhill Experience For the first time ever, we are inviting people to spend a weekend with us and really learn how Summerhill works – How do we do Safeguarding Children? How do we prepare for school inspections? What exams do we offer? How do our teachers approach their roles? How do the pupils feel about their own roles and lives in the school and afterwards? It will include A.S. Neill’s founding principles, the famous Self-Government Meetings, policies, paperwork, teaching and a chance to talk to adults and pupils. It is also a chance to just hang out in this unique historic environment and chill! Profits will go to the building of the new A.S. -

Family Services: the Teams and the Education Settings They Support: Academic Year 2020 / 2021

Family Services: The Teams and the Education Settings They Support: Academic Year 2020 / 2021 The SEND Family Services (within SCC Inclusion Service) lead on the support of children, young people and their families so that with the necessary skills, young people progress into adulthood to further achieve their hopes, dreams and ambitions. Fundamental to this is our joint partner commitment to the delivery of services through a key working approach for all. The six locality-based Family Services Teams: • Guide children, young people and their families through their education pathway and/or SEND Journey • Support children and young people who are at risk of exclusion or who have been permanently excluded • Ensure that assessments, including education, health and care needs assessments, provide accurate information and clear advice and are delivered within timescales • Monitor the progress of children and young people with SEND in achieving outcomes to prepare them for adulthood and offer support and guidance at transition points Team members will: • Create trusting relationships with children, young people and families by delivering what they agree to do • Build effective communication and relationships with professionals, practitioners and education settings • Enable the person receiving a service to feel able to discuss any areas of concern / issues and that appropriate action will be taken • Be transparent and honest in the message they are delivering to all, and will give a clear overview of the processes and procedures • Be effective advocates for children, young people and families For young people and families, mainstream schools, local alternative provision and specialist schools, settings and units, your primary contacts will be the Family Services Co-ordinators and Assistant Co-ordinators. -

Neill and Summerhill

The Magazine of Alternative Education Education Revolution I s s u e N u m b e r F o r t y Winter/Spring 2005 $4.95 USA/ Neill and Summerhill also: Idec in India w w w . E d u c a t i o n R e v o l u t i o n . o r g Education Revolution The Magazine of Alternative Education Fall 2004 - Issue Number Thirty Nine - www.educationrevolution.org The mission of The Education Revolution magazine is based Looking for News on that of the Alternative Education Resource Organization Funding Shell Game.......................................... 4 (AERO): “Building the critical mass for the education revolution Secretary of NCLB............................................. 5 by providing resources which support self-determination in IDEC in India learning and the natural genius in everyone.” Towards this Jerry Mintz................................................... 5 end, this magazine includes the latest news and communications regarding the broad spectrum of educational alternatives: public Booroobin alternatives, independent and private alternatives, home Derek Sheppard.............................................. 7 education, international alternatives, and more. The common feature in all these educational options is that they are learner- Being There centered, focused on the interest of the child rather than on an Butterflies........................................................... 9 arbitrary curriculum. AERO, which produces this magazine quarterly, is firmly Mail & Communication established as a leader in the field of educational alternatives. Main Section..................................................... 13 Founded in 1989 in an effort to promote learner-centered 16 education and influence change in the education system, AERO Home Education............................................... is an arm of the School of Living, a non-profit organization. Public Alternatives............................................ 17 AERO provides information, resources and guidance to International News........................................... -

Profile: Michael Newman

Profile: Michael Newman Michael Newman is a qualified secondary school science teacher who has been actively involved in citizenship, enterprise and values education since 1988. He has worked at Summerhill School for over eleven years as a science teacher, curriculum adviser, houseparent, English teacher and primary teacher. He has been on the executive committees of the Children’s Rights Alliance for England (secretary and treasurer), the British Humanist Association, Society for Storyteller’s Education Committee, Ipswich and Norwich Co-op Education Committee, Suffolk County Citizenship Education Steering Group and the A.S.Neill’s Summerhill Trust. He has contributed to numerous conferences and supported Summerhill students contributing to the UN Special Session on the Child (NGO delegates), UNESCO’s conference of education ministers in Geneva (under the IBE). He organised the first three Dover Schools Conferences with students from Summerhill School as facilitators, involving 14 local secondary schools. He chaired the International Democratic Education Conference 1999. He has organised Summerhill School holding its full community meetings in front of invited guests at the House of Commons and London’s City Hall. He has lobbied with Summerhill students the UK government to promote the values and ideas of Summerhill. He was the facilitator of the school’s student action group fighting to save the school from government closure in 1999-2000 (dramatised on Childrens BBC as ‘Summerhill’). For eight years he has worked in East London as a development education school’s project worker, running events, projects, training and conferences for children and teachers on co-operative enterprise, children’s rights, local democracy, restorative justice and the use of ICT in citizenship. -

University Mkzrcxilms International 300 N, ZEEB RD

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.