Media: Industry Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PSB Report Definitions

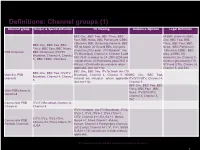

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, It’s been really heart-warming to read all your lovely letters and emails of support about what Talking Pictures TV has meant to you during lockdown, it means so very much to us here in the projectionist’s box, thank you. So nice to feel we have helped so many of you in some small way. Spring is on the horizon, thank goodness, and hopefully better times ahead for us all! This month we are delighted to release the charming filmThe Angel Who Pawned Her Harp, the perfect tonic, starring Felix Aylmer & Diane Cilento, beautifully restored, with optional subtitles plus London locations in and around Islington such as Upper Street, Liverpool Road and the Regent’s Canal. We also have music from The Shadows, dearly missed Peter Vaughan’s brilliant book; the John Betjeman Collection for lovers of English architecture, a special DVD sale from our friends at Strawberry, British Pathé’s 1950 A Year to Remember, a special price on our box set of Together and the crossword is back! Also a brilliant book and CD set for fans of Skiffle and – (drum roll) – The Talking Pictures TV Limited Edition Baseball Cap is finally here – hand made in England! And much, much more. Talking Pictures TV continues to bring you brilliant premieres including our new Saturday Morning Pictures, 9am to 12 midday every Saturday. Other films to look forward to this month include Theirs is the Glory, 21 Days with Vivien Leigh & Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith’s Fanny By Gaslight, The Spanish Gardener with Dirk Bogarde, Nijinsky with Alan Bates, Woman Hater with Stewart Granger and Edwige Feuillère,Traveller’s Joy with Googie Withers, The Colour of Money with Paul Newman and Tom Cruise and Dangerous Davies, The Last Detective with Bernard Cribbins. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (Eds.)

From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) RIPE @ 2007 NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) NORDICOM From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media RIPE@2007 Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Jo Bardoel (eds.) © Editorial matters and selections, the editors; articles, individual con- tributors; Nordicom ISBN 978-91-89471-53-5 Published by: Nordicom Göteborg University Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG Sweden Cover by: Roger Palmqvist Cover photo by: Arja Lento Printed by: Livréna AB, Kungälv, Sweden, 2007 Environmental certification according to ISO 14001 Contents Preface 7 Jo Bardoel and Gregory Ferrell Lowe From Public Service Broadcasting to Public Service Media. The Core Challenge 9 PSM platforms: POLICY & strategY Karol Jakubowicz Public Service Broadcasting in the 21st Century. What Chance for a New Beginning? 29 Hallvard Moe Commercial Services, Enclosure and Legitimacy. Comparing Contexts and Strategies for PSM Funding and Development 51 Andra Leurdijk Public Service Media Dilemmas and Regulation in a Converging Media Landscape 71 Steven Barnett Can the Public Service Broadcaster Survive? Renewal and Compromise in the New BBC Charter 87 Richard van der Wurff Focus on Audiences. Public Service Media in the Market Place 105 Teemu Palokangas The Public Service Entertainment Mission. From Historic Periphery to Contemporary Core 119 PSM PROGRAMMES: strategY & tacticS Yngvar Kjus Ideals and Complications in Audience Participation for PSM. Open Up or Hold Back? 135 Brian McNair Current Affairs in British Public Service Broadcasting. Challenges and Opportunities 151 Irene Costera Meijer ‘Checking, Snacking and Bodysnatching’. -

Diversity and Inclusion in the European Audiovisual Sector European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2021 ISSN 2079-1062 ISBN 978-92-871-9054-3 (Print Version)

Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector IRIS Plus IRIS Plus 2021-1 Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2021 ISSN 2079-1062 ISBN 978-92-871-9054-3 (Print version) Director of publication – Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision – Maja Cappello, Head of Department for Legal Information Editorial team – Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Research assistant - Léa Chochon European Audiovisual Observatory Authors (in alphabetical order) Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Translation Marco Polo Sarl, Sonja Schmidt Proofreading Jackie McLelland, Johanna Fell, Catherine Koleda Editorial assistant – Sabine Bouajaja Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76, allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, France Please quote this publication as Cabrera Blázquez F.J., Cappello M., Talavera Milla J., Valais S., Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector, IRIS Plus, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, April 2021 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2021 Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the views of the Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. Diversity and inclusion in the European audiovisual sector Francisco Javier Cabrera Blázquez, Maja Cappello, Julio Talavera Milla, Sophie Valais Foreword Let me tell you a few stories about extraordinary people. Artemisia Gentileschi was a seventeenth century painter, and quite a talented one at that. -

The BBC's Use of Spectrum

The BBC’s Efficient and Effective use of Spectrum Review by Deloitte & Touche LLP commissioned by the BBC Trust’s Finance and Strategy Committee BBC’s Trust Response to the Deloitte & Touche LLPValue for Money study It is the responsibility of the BBC Trust,under the As the report acknowledges the BBC’s focus since Royal Charter,to ensure that Value for Money is the launch of Freeview on maximising the reach achieved by the BBC through its spending of the of the service, the robustness of the signal and licence fee. the picture quality has supported the development In order to fulfil this responsibility,the Trust and success of the digital terrestrial television commissions and publishes a series of independent (DTT) platform. Freeview is now established as the Value for Money reviews each year after discussing most popular digital TV platform. its programme with the Comptroller and Auditor This has led to increased demand for capacity General – the head of the National Audit Office as the BBC and other broadcasters develop (NAO).The reviews are undertaken by the NAO aspirations for new services such as high definition or other external agencies. television. Since capacity on the platform is finite, This study,commissioned by the Trust’s Finance the opportunity costs of spectrum use are high. and Strategy Committee on behalf of the Trust and The BBC must now change its focus from building undertaken by Deloitte & Touche LLP (“Deloitte”), the DTT platform to ensuring that it uses its looks at how efficiently and effectively the BBC spectrum capacity as efficiently as possible and uses the spectrum available to it, and provides provides maximum Value for Money to licence insight into the future challenges and opportunities payers.The BBC Executive affirms this position facing the BBC in the use of the spectrum. -

Summary of Hearing with the British Film Institute Held on 12 June 2013

CINEWORLD/CITY SCREEN MERGER INQUIRY Summary of hearing with the British Film Institute held on 12 June 2013 Background 1. The British Film Institute (BFI) was the appointed lead agency for film in the UK, which gave it a strategic remit for film production. Its functions included the Lottery Film Fund, which distributed lottery money for film development, film production and the distribution of specialized film in the UK; an archive team, which looked after and restored works; an education team; and a publishing function for magazine and DVD publication. 2. The BFI had an exhibition department, which was based at the BFI Southbank and also housed the London Film Festival and the Lesbian and Gay Film Festival. BFI Southbank was a commercially-operated cinema in London and the site also housed the Mediatheque, a publicly available archive of television and media material and the Reuben library of books and manuscripts related to film and television. It owned the IMAX cinema on the Southbank, the running of which was contracted to the Odeon. 3. The BFI had a distribution arm, distributing works restored by the BFI as well as third- party films. These tended to be specialized, rather than commercial films. The BFI was not a competitive acquirer of rights to new works. 4. As a charity, the BFI also had a fundraising team. BFI grants 5. The BFI would shortly be launching a fund called The Audience Network to allow community venues to show a broad range of films to their local audience. Through the fund, it would make available small grants for equipment to venues that were not cinemas, for example village halls, town halls and local schools that ran film societies or film clubs. -

Scotland's Home of News and Entertainment

Scotland’s home of news and entertainment Strategy Update May 2018 STV in 2020 • A truly multi-platform media company with a balanced profit base across broadcast, production and digital o Expect around 1/3rd of profit from sources other than linear spot advertising (vs 17% today) • A magnet for the best creative talent from Scotland and beyond • A brand famous for a range of high quality programming and accessible by all Scots wherever they are in the world via the STV app • One of the UK’s leading producers, making world class returning series for a range of domestic and international players • Working in partnership with creative talent, advertisers, businesses and Government to drive the Scottish economy and showcase Scotland to the world Scotland’s home of news and entertainment 2 We have a number of strengths and areas of competitive advantage Strong, trusted brand Unrivalled Talented, connection with committed people Scottish viewers and advertisers Robust balance sheet and growing Scotland’s most returns to powerful marketing shareholders platform Settled A production relationship with business well ITV which placed for incentivises STV Profitable, growing “nations and to go digital digital business regions” growth holding valuable data 3 However, there is also significant potential for improvement •STV not famous for enough new programming beyond news •STV brand perceived as ageing and safe BROADCAST •STV2 not cutting through •News very broadcast-centric and does not embrace digital •STV Player user experience lags competition -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 AUGUST/SEPT 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 AUGUST/SEPT 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping you are all well and enjoying a Lyons Maid or two on the hotter days while watching Talking Pictures TV – your own personal trip to the flicks every day and no fleas! This month we bring you a wonderful new DVD Box set from Renown Pictures – The Comedy Collection Volume 3! We thought it was time we all had a jolly good laugh and with 11 films over 3 discs, starring some of the greatest British character actors you will see, it’s an absolute bargain at £20 for all 3 discs with free UK postage. Titles include: A Hole Lot of Trouble with Arthur Lowe, Victor Maddern and Bill Maynard; A Touch of The Sun with Frankie Howerd, Ruby Murray and Alfie Bass, once lost British comedy Just William’s Luck, fully restored to its former glory, Come Back Peter, with Patrick Holt and Charles Lamb, also once lost and never before released on DVD, as well as Where There’s A Will with George Cole and Kathleen Harrison, plus many more! More details overleaf. There’s an extra special deal on our Comedy Collection Volumes 1 and 2 as well. Regarding our events this year and next year, there is good news and bad news. Finally, the manager at the St Albans Arena has come back to the office and has secured 28th March 2021 for us. Sad news as it doesn’t look like we will be able to go ahead with any other event this year, including Stockport on Sunday 4th October. -

General Terms for BBC World Service Radio Programme

THE BBC’S GENERAL TERMS FOR THE PRODUCTION OF WORLD SERVICE RADIO PROGRAMMES BY INDEPENDENT PRODUCERS (2011) Index Page 1. Definitions 1 2. Interpretation 10 3. The BBC Representatives 11 4. Contractual Pre-Conditions 11 5. Production 11 6. Production/Talent Contracts 12 7. Finance 16 8. Insurance 18 9. Editorial Process 19 10. Credits and Copyright Notice 21 11. Delivery 21 12. Rights Granted to the BBC 21 13. Publicity/Promotion/Marketing/Trails 26 14. Licence Period 27 15. Pre-Paid Uses and Payment for Further Uses 28 16. Distribution/Exploitation 30 17. Warranties and Indemnities 35 18. Takeover 37 19. Abandonment of Production 39 20. Termination 39 21. Force Majeure 40 22. Recommissioning Right 41 23. Confidentiality 41 24. Notices 42 - 1 - 25. General 42 26. Post-Licence Provisions 45 Schedule 5 Trade Mark Schedule 46 Schedule 6 Excerpt from Charter 53 - 2 - The BBC’s General Terms for the Production of World Service Radio Programmes by Independent Producers (2011) 1. DEFINITIONS In this Agreement unless the context otherwise requires the following expressions shall have the following meanings: “Additional Licence Fee” – the sum payable to the Producer by the BBC under General Term 14 as an advance against the payment due to the Producer for 1 package of further uses under General Term 15.2; “Advances” – as defined in General Term 7.2.1; “Agreement” - the Programme production agreement between the BBC and the Producer which includes all schedules hereto (including Schedules 1 to 4); “Audio Publishing Rights” - the right to adapt, -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third -

The Future of Public Service Broadcasting

House of Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The future of public service broadcasting Sixth Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the Report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 17 March 2021 HC 156 Published on 25 March 2021 by authority of the House of Commons The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Julian Knight MP (Conservative, Solihull) (Chair) Kevin Brennan MP (Labour, Cardiff West) Steve Brine MP (Conservative, Winchester) Alex Davies-Jones MP (Labour, Pontypridd) Clive Efford MP (Labour, Eltham) Julie Elliott MP (Labour, Sunderland Central) Rt Hon Damian Green MP (Conservative, Ashford) Rt Hon Damian Hinds MP (Conservative, East Hampshire) John Nicolson MP (Scottish National Party, Ochil and South Perthshire) Giles Watling MP (Conservative, Clacton) Heather Wheeler MP (Conservative, South Derbyshire) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright-parliament/. Committee Reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/dcmscom and in print by Order of the House.