The Future of Public Service Broadcasting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC Member for England Role Specification

BBC Member for England The BBC’s mission is defined by Royal Charter: to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain. The BBC is required to do this through delivering five public purposes: 1. To provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them; 2. To support learning for people of all ages; 3. To show the most creative, highest quality and distinctive output and services; 4. To reflect, represent and serve the diverse communities of all of the United Kingdom’s nations and regions and, in doing so, support the creative economy across the United Kingdom; and, 5. To reflect the United Kingdom, its culture and values to the world. The BBC is a public corporation, independent in all matters concerning the fulfilment of its mission and the promotion of the public purposes. It is funded primarily by the licence fee and has a subsidiary commercial operation, which supports the delivery of the Corporation’s mission and public purposes. Each year the BBC is required to publish an Annual Plan, setting out details of its creative remit for the forthcoming year, and an Annual Report and Accounts, reporting back on performance in the previous year. Copies of these can be found here and here. The BBC’s activities and services The BBC Board is responsible for the operation of the entirety of the BBC Group, which includes both the public service broadcasting responsibilities as well as its commercial operations, both in the UK and around the world. -

Intergenerational Solidarity and the Needs of Future Generations

United Nations A/68/x.. General Assembly Distr.: General 5 August 2013 Original: English Word count (including footnotes/endnotes): 8419 Sixty-eighth session Item 19 of the provisional agenda Sustainable Development: Intergenerational solidarity and the needs of future generations Report of the Secretary-General Summary The present report is prepared pursuant to paragraph 86 of the Rio+20 outcome document, which requests the Secretary-General to provide a report on the need for promoting intergenerational solidarity for the achievement of sustainable development, taking into account the needs of future generations. The report evaluates how the need for intergenerational solidarity could be addressed by the United Nations system and analyses how the issue of intergenerational solidarity is embedded in the concept of sustainable development and existing treaties, and declarations, resolutions, and intergovernmental decisions. It also reviews the conceptual A/68/100 A/68/x.. and ethical underpinnings of intergenerational solidarity and future generations and how the issue has been taken into consideration in policy-making at the national level in a variety of institutions. The report outlines options for possible models to institutionalize concern for future generations at the United Nations level, as well as suggesting options for the way forward. 2 A/68/x.. Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction………………………………………… II. Conceptual framework (a) Conceptual and ethical dimensions (b) Economics III. Existing arrangements and lessons learnt (a) Needs of future generations in international legal instruments (b) Legal provisions at the national level (c) National institutions for future generations (d) Children and youth (e) Proposals related to a High Commissioner for Future Generations IV. -

Video Trends Report Q2 2019

1 VIDEO TRENDS REPORT Q2 2019 © 2019 TiVo Corporation. Introduction 2 Survey Methodology Q2 2019 Survey Size INTRODUCTION 5,340 Geographic Regions U.S., Canada TiVo seeks real consumer opinions to uncover key trends relevant to TV providers, digital publishers, advertisers and consumer electronics manufacturers for our survey, which is administered quarterly and examined biannually in this Age of Respondents published report. We share genuine, unbiased perspectives and feedback from viewers to give video service providers 18+ and industry stakeholders insights for improving and enhancing the overall TV-viewing experience for consumers. TiVo has conducted a quarterly consumer survey since 2012, enabling us to monitor, track and identify key trends in viewing This survey was conducted in Q2 2019 by a leading habits, in addition to compiling opinions about video providers, emerging technologies, connected devices, OTT apps and third-party survey service; TiVo analyzed the results. content discovery features, including personalized recommendations and search. TiVo conducts this survey on a quarterly basis and publishes a biannual report evaluating and analyzing TiVo (NASDAQ: TIVO) brings entertainment together, making it easy to find, watch and enjoy. We serve up the best key trends across the TV industry. movies, shows and videos from across live TV, on-demand, streaming services and countless apps, helping people to watch on their terms. For studios, networks and advertisers, TiVo delivers a passionate group of watchers to increase viewership and engagement across all screens. Go to tivo.com and enjoy watching. For more information about TiVo’s solutions for the media and entertainment industry, visit business.tivo.com or follow us on Twitter @tivoforbusiness. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

ITV Partners with Viewability Company Meetrics

PRESS RELEASE ITV partners with viewability company Meetrics First measurements across all channels show viewability rates above industry-wide benchmarks ITV, the UK’s biggest commercial broadcaster, announces that it has partnered with Meetrics, a leading European software company for advertising measurement and analytics, to provide enhanced advertising campaign delivery validation for VOD advertising across ITV Hub platforms. As part of the partnership, Meetrics provides video viewability data and reporting for ITV Hub on connected TV platforms and In-App (Android and iOS) as well as desktop and mobile web campaigns. This enriches the reporting capabilities for VOD campaigns run on ITV Hub and demonstrates the high quality of ITV’s ad inventory on metrics that are important to agencies and advertisers. With the partnership, ITV underlines its commitment to very high transparency standards and quality controls for the benefit of its advertising customers. Meetrics is an independent vendor accredited for various services by the Media Rating Council and committed to strict privacy rules in full accordance with GDPR. With Meetrics as a partner ITV is breaking new ground by being the first broadcaster in the world to make use of the IAB Open Measurement SDK, which is considered the most rigorous standard for In-App viewability measurement. To date, average measurement for campaigns running across ITV Hub showed a viewability rate (according to the MRC definition) of 98%, which is far beyond average, compared to industry viewability benchmarks. The new viewability measurement and reporting will give advertisers huge confidence that ITV can deliver standards on human and viewability measures that outperform the VOD market. -

Quick Reference Guide To: How to Deliver Content to ITV Your Programme Has Been Commissioned and You Have Been Asked by ITV to Deliver a Piece of Content

July 2020 Quick Reference Guide To: How to Deliver Content to ITV Your programme has been commissioned and you have been asked by ITV to deliver a piece of content. What do you need to do and who are the contacts along the journey?..... Firstly, you will need to know who your Compliance Advisor is. If you’ve not been provided with a contact then email [email protected]. Your Advisor will be able to provide you with legal advice along the journey and will be able to provide you with lots of key information such as your unique Production Number. Another key contact is your Commissioner. They may require some deliverables from you so it’s best to have that discussion directly with them. Within this guide you will find a list of frequently asked questions with links to more detailed documents. 1. My programme will be transmitted live. Does this make a difference? 2. My programme isn’t live; so what exactly am I delivering? 3. Where do I get my Production/Clock Numbers from? 4. Where can I get my tech spec to file deliver? 5. Where do I deliver my DPP AS-11 file to? 6. I need to ensure that my programme has the ITV ‘Look & Feel’. How do I make this happen? 7. Can I make amendments to my programme after I’ve delivered it to Content Delivery? 8. Where do I send my Post Productions Scripts to? 9. What do I do if I have queries around part durations and the total runtime of my programme? 10. -

Ofcom Annual Report and Accounts 2020-21

The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 HC 459 The Office of Communications Annual Report and Accounts For the period 1 April 2020 to 31 March 2021 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraphs 11 and 12 of Schedule 1 of the Office of Communications Act 2002 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 8 July 2021. Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers Laid before the Welsh Parliament by the Rt Hon Mark Drakeford MS, the First Minister of Wales HC 459 © Ofcom Copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. ISBN 978-1-5286-2705-4 CCS0521569280 07/21 SG/2021/123 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Printed in the UK by Hobbs the Printers on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Chair’s Message 4 Chief Executive’s Report 6 Section A: Performance Report 8 Overview 9 Performance Review 11 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 43 Stakeholder Engagement 47 Financial Review 55 Corporate Responsibility 61 Sustainability Report 64 Section B: Accountability Report 66 Governance 67 Our Employees 92 Remuneration Report 96 The Certificate and Report of the Comptroller 103 and Auditor General to the Houses of Parliament Section C: Financial Statements 106 Statement of Income and Expenditure 107 Statement of Comprehensive Net Expenditure 107 Statement of Financial Position 108 Statement of Changes in Equity 109 Statement of Cash Flows 110 Notes to the Accounts 111 Section D: Annexes 148 A1. -

Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations

Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations Science and Environmental Health Network The International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School Models for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations Science and Environmental Health Network The International Human Rights Clinic at Harvard Law School October 2008 http://www.sehn.org http://www.law.harvard.edu/programs/hrp The Science & Environmental Health Network (“SEHN”) engages communities and governments in the effective application of science to restore and protect public and ecosystem health. SEHN is a leading proponent of the precautionary principle as a basis for public policy. Our goal is policy reform that promotes just and sustainable communities, for this and future generations. The International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) at Harvard Law School is a center for critical thought and active engagement in human rights. The IHRC provides students the opportunity to engage directly with the vital issues, insti- tutions and processes of the human rights movement. Each year, the IHRC part- ners with dozens of local and international non-governmental organizations to work on human rights projects ranging from litigation, on-site investigations, legal and policy analysis, report drafting for international oversight bodies, and the development of advocacy strategies. MODELS FOR PROTECTING THE ENVIRONMENT FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS Table of Contents I. Summary 1 II. Legal Bases for Present Promotion of Future Interests 3 A. The Interests of Future Generations 4 B. Duties to and Rights of Future Generations 6 C. Guardians and Trustees for Future Generations 9 III. Legal Mechanisms and Institutions for Protecting the Environment for Future Generations 11 A. -

Statement: Ofcom's Plan of Work 2021/22

Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 Making communications work for everyone Ofcom’s plan of work 2021/22 – Welsh translation STATEMENT: Publication Date: 26 March 2021 Contents Section 1. Chief Executive’s foreword 1 2. Overview 3 3. Our goals and priorities for 2021/22 9 4. Delivering good outcomes for consumers across the UK 31 Annex A1. What we do 37 A2. Project work for 2021/2022 39 Plan of Work 2021/22 1. Chief Executive’s foreword Ofcom is the UK’s communications regulator, with a mission to make communications work for everyone. We serve the interests of consumers and businesses across the UK’s nations and regions, through our work in mobile and fixed telecoms, broadcasting, spectrum, post and online services. Over the past year we have learned that being connected is everything. High-quality, reliable communications services have never mattered more to people’s lives. But as consumers shift their habits increasingly online, our communications sectors are transforming fast. It is an exciting moment for our industries and for Ofcom as a regulator - it requires long-term focus alongside speed and agility in response to change. Against this backdrop our statement sets out our detailed goals for the coming financial year, and how we plan to achieve them. On telecoms, Ofcom has just confirmed a new long-term framework for investment in gigabit- capable fixed networks. In the coming year, we will shift our focus to support delivery against this programme, alongside investment and innovation in 5G and new mobile infrastructure. Following legislation in Parliament, we will put in place new rules to hold operators to account for the security and resilience of their networks. -

Media: Industry Overview

MEDIA: INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 7 This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: uk.practicallaw.com/w-022-5168 Get more information on Practical Law and request a free trial at: www.practicallaw.com This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. RESOURCE INFORMATION by Lisbeth Savill, Clare Hardwick, Rachael Astin and Emma Pianta, Latham & Watkins, LLP RESOURCE ID w-022-5168 CONTENTS RESOURCE TYPE • Scope of this note • Publishing and the press Sector note • Film • Podcasts and digital audiobooks CREATED ON – Production • Advertising 13 November 2019 – Financing and distribution • Recorded music JURISDICTION • Television • Video games United Kingdom – Production • Radio – Linear and catch-up television • Social media – Video on-demand and video-sharing services • Media sector litigation SCOPE OF THIS NOTE This note provides an overview of the sub-sectors within the UK media industry. Although the note is broken down by sub-sector, in practice, many of these areas overlap in the converged media landscape. For more detailed notes on media industry sub-sectors, see: • Sector note, Recorded music industry overview. • Sector note, TV and fi lm industry overview. • Practice note, Video games industry overview. FILM Production Total UK spend on feature fi lms in 2017 was £2 billion (up 17% on 2016) (see British Film Institute (BFI): Statistical Yearbook 2018). Film production activity in the UK is driven by various factors, including infrastructure, facilities, availability of skills and creative talent and the incentive of fi lm tax relief (for further information, see Practice note, Film tax relief). UK-produced fi lms can broadly be sub-divided into independent fi lms, UK studio-backed fi lms and non-UK fi lms made in the UK. -

AT2400 Alltouch® Remote Control How Do I Program the Mode Keys? What If None of the Codes Work? the Same Time, Regardless of the Current Mode

FCC Compliance Setting Up Your Remote (continued) User’s Guide Can I Change My Volume Control? Can I Change My Channel Control? This device complies with Part 15 of the FCC Rules. You can program your Volume and Mute keys to By default, the channel keys on your remote (CH+, Operation is subject to the following two conditions: function in one of two ways: CH-, digits 0-9, and Last) let you change channels (1) This device may not cause harmful interference, • To control the volume on a single device all on the set-top, the TV, or a VCR, depending on the and (2) this device must accept any interference the time current mode. You can disable or enable channel received, including interference that may cause control for the TV or VCR mode. Also, if you have ® • To control the volume on each device, AT2400 AllTouch undesired operation. reassigned your AUX key to control a second TV depending on the mode key that you press or VCR, you can disable or enable channel control Note Remote Control Note: The default setting is to control volume for that device as well. See Reassigning Mode This equipment has been tested and found to comply through your TV all the time. Keys, earlier in this section, for more information. with the limits for a class B digital device, pursuant Follow these steps to change the way your Volume If you disable the channel control for a TV or VCR, to Part 15 of the FCC Rules. These limits are and Mute keys function. -

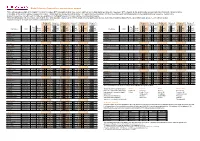

Digital Television Transmitters: Pre-Switchover Network

Digital Television Transmitters: pre-switchover network This leaflet provides details of the Digital Terrestrial Television (DTT) transmitters which have not yet switched over to fully-digital operation (the 'low power' DTT network). Detailed information on post-switchover transmitter characteristics is available on the Ofcom website at www.ofcom.org.uk. Transmitters are grouped according to the ITV1 region that they broadcast, which will determine each transmitter's place in the digital switchover sequence. Details of the programme services carried in each multiplex are available on the Digital Television Group's website, www.dtg.org.uk/retailer. While this information is believed to be correct at the time of preparation, changes to the DTT network will occur, particularly as more transmitters switch to digital. For the latest information, please see the Ofcom website, www.ofcom.org.uk, or Digital UK's website, www.digitaluk.co.uk. Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D Multiplex 1 Multiplex 2 Multiplex A Multiplex B Multiplex C Multiplex D BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva BBC Digital 3&4 SDN BBC Arqiva Arqiva Avg. Avg. Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Aerial ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP ERP Site Name NGR Aerial Site Name NGR Aerial Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Group (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) (kW) Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Offset Height Offset Height Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Channel Anglia Tyne Tees