OPERATING OR WRECKING at the NATIONAL RAILWAY MUSEUM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partial List of Institutional Clients

Lord Cultural Resources has completed over 2500 museum planning projects in 57+ countries on 6 continents. North America Austria Turkey Israel Canada Belgium Ukraine Japan Mexico Czech Republic United Kingdom Jordan USA Estonia Korea Africa France Kuwait Egypt Central America Germany Lebanon Morocco Belize Hungary Malaysia Namibia Costa Rica Iceland Philippines Nigeria Guatemala Ireland Qatar South Africa Italy Saudi Arabia The Caribbean Tunisia Aruba Latvia Singapore Bermuda Liechtenstein Asia Taiwan Trinidad & Tobago Luxembourg Azerbaijan Thailand Poland Bahrain United Arab Emirates South America Russia Bangladesh Oceania Brazil Spain Brunei Australia Sweden China Europe New Zealand Andorra Switzerland India CLIENT LIST Delta Museum and Archives, Ladner North America The Haisla Nation, Kitamaat Village Council Kamloops Art Gallery Canada Kitimat Centennial Museum Association Maritime Museum of British Columbia, Victoria Alberta Museum at Campbell River Alberta Culture and Multiculturalism Museum of Northern British Columbia, Alberta College of Art and Design (ACAD), Calgary Prince Rupert Alberta Tourism Nanaimo Centennial Museum and Archives Alberta Foundation for the Arts North Vancouver Museum Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton Port Alberni Valley Museum Barr Colony Heritage Cultural Centre, Lloydminster Prince George Art Gallery Boreal Centre for Bird Conservation, Slave Lake National Historic Site, Port Alberni Canada West Military Museums, Calgary R.B. McLean Lumber Co. Canadian Pacific Railway, Calgary Richmond Olympic Experience -

Submissionversion

SILEBY NEIGHBOURHOOD PLAN 2018 – 2036 Submission version Page left deliberately blank 2 Contents Chapter heading Page Foreword from the Chair 4 1. Introduction 6 2. How the Neighbourhood Plan fits into the planning system 8 3. The Plan, its vision, objectives and what we want it to achieve 10 4. How the Plan was prepared 12 5. Our Parish 14 6. Meeting the requirement for sustainable development 19 7. Neighbourhood Plan Policies 20 General 20 Housing 26 The Natural and Historic Environment 35 Community Facilities 58 Transport 65 Employment 74 8. Monitoring and Review 78 Appendix 1 – Basic Condition Statement (with submission version) Appendix 2 – Consultation Statement (with submission version) Appendix 3 – Census Data, Housing Needs Report and SSA report Appendix 4 – Environmental Inventory Appendix 5 – Local Green Space Assessments Appendix 6 – Buildings and Structures of local significance Appendix 7 – Study of traffic flows in Sileby (transport appendices) 3 Foreword The process of creating the Sileby Neighbourhood Plan has been driven by Parish Councillors and members of the community and is part of the Government’s approach to planning contained in the Localism Act of 2011. Local people now have a greater say through the planning process about what happens in the area in which they live by preparing a Neighbourhood Plan that sets out policies that meet the need of the community whilst having regard for local, national and EU policies. The aim of this Neighbourhood Plan is to build and learn from previous community engagement and village plans and put forward clear wishes of the community regarding future development. -

Viimeinen Päivitys 8

Versio 20.10.2012 (222 siv.). HÖYRY-, TEOLLISUUS- JA LIIKENNEHISTORIAA MAAILMALLA. INDUSTRIAL AND TRANSPORTATION HERITAGE IN THE WORLD. (http://www.steamengine.fi/) Suomen Höyrykoneyhdistys ry. The Steam Engine Society of Finland. © Erkki Härö [email protected] Sisältöryhmitys: Index: 1.A. Höyry-yhdistykset, verkostot. Societies, Associations, Networks related to the Steam Heritage. 1.B. Höyrymuseot. Steam Museums. 2. Teollisuusperinneyhdistykset ja verkostot. Industrial Heritage Associations and Networks. 3. Laajat teollisuusmuseot, tiedekeskukset. Main Industrial Museums, Science Centres. 4. Energiantuotanto, voimalat. Energy, Power Stations. 5.A. Paperi ja pahvi. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Paper and Cardboard History. Associations and Networks. 5.B. Paperi ja pahvi. Museot. Paper and Cardboard. Museums. 6. Puusepänteollisuus, sahat ja uitto jne. Sawmills, Timber Floating, Woodworking, Carpentry etc. 7.A. Metalliruukit, metalliteollisuus. Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Associations and Networks. 7.B. Ruukki- ja metalliteollisuusmuseot. Ironworks, Metallurgy. Museums. 1 8. Konepajateollisuus, koneet. Yhdistykset ja museot. Mechanical Works, Machinery. Associations and Museums. 9.A. Kaivokset ja louhokset (metallit, savi, kivi, kalkki). Yhdistykset ja verkostot. Mining, Quarrying, Peat etc. Associations and Networks. 9.B. Kaivosmuseot. Mining Museums. 10. Tiiliteollisuus. Brick Industry. 11. Lasiteollisuus, keramiikka. Glass, Clayware etc. 12.A. Tekstiiliteollisuus, nahka. Verkostot. Textile Industry, Leather. Networks. -

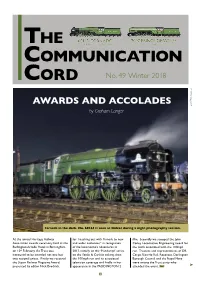

Didcot Railway CENTRE

THE COMMUNICATION ORD No. 49 Winter 2018 C Shapland Andrew AWARDS AND ACCOLADES by Graham Langer Tornado in the dark. No. 60163 is seen at Didcot during a night photography session. At the annual Heritage Railway for “reaching out with Tornado to new film. Secondly we scooped the John Association awards ceremony held at the and wider audiences” in recognition Coiley Locomotive Engineering award for Burlington Arcade Hotel in Birmingham of the locomotive’s adventures in the work associated with the 100mph on 10th February, the Trust was 2017, initially on the ‘Plandampf’ series run. Trustees and representatives of DB honoured to be awarded not one but on the Settle & Carlisle railway, then Cargo, Ricardo Rail, Resonate, Darlington two national prizes. Firstly we received the 100mph run and its associated Borough Council and the Royal Navy the Steam Railway Magazine Award, television coverage and finally in her were among the Trust party who ➤ presented by editor Nick Brodrick, appearance in the PADDINGTON 2 attended the event. TCC 1 Gwynn Jones CONTENTS EDItorIAL by Graham Langer PAGE 1-2 Mandy Gran Even while Tornado Awards and Accolades up his own company Paul was Head of PAGE 3 was safely tucked Procurement for Northern Rail and Editorial up at Locomotive previously Head of Property for Arriva Tornado helps Blue Peter Maintenance Services Trains Northern. t PAGE 4 in Loughborough Daniela Filova,´ from Pardubice in the Tim Godfrey – an obituary for winter overhaul, Czech Republic, joined the Trust as Richard Hardy – an obituary she continued to Assistant Mechanical Engineer to David PAGE 5 generate headlines Elliott. -

Fall New Items 2017

Gelesen Korrektur an Märklin Freigabe Märklin Daten an Marieni Fall New Items 2017 E Gelesen Korrektur an Märklin Freigabe Märklin Daten an Marieni Editorial Contents “Truly Impressive” and “Elegant Travel” Birthday Locomotive ..................................................... 3 MHI Exclusiv H0 .......................................................... 4 You can get to the heart of this year‘s fall new items from the Märklin Immense operating fun awaits you in the smallest gauge from Märklin. H0 ........................................................................... 14 “blacksmith” with these simple yet significant words. For this fall, true It is comfortable in the Intercity right through Germany – exactly the same H0 Accessories ........................................................... 24 classics are claiming priority on your model railroad layout. The last way you write the schedule. MHI Exclusiv Z Gauge ................................................... 25 class 18.5 running in service with its appropriate express train car set Z Gauge .................................................................... 26 from the Sixties will awaken delightful travel memories. A somewhat Marvelously detailed and really well arrayed is the way the former “jack- 1 Gauge .................................................................... 27 different but equally appreciative view is trained on our new MHI special of-all-trades” is greeting your for 1 Gauge. Our E 44 from the Bamberg Explanations of Symbols ............................................... -

The Evolution of the Steam Locomotive, 1803 to 1898 (1899)

> g s J> ° "^ Q as : F7 lA-dh-**^) THE EVOLUTION OF THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE (1803 to 1898.) BY Q. A. SEKON, Editor of the "Railway Magazine" and "Hallway Year Book, Author of "A History of the Great Western Railway," *•., 4*. SECOND EDITION (Enlarged). £on&on THE RAILWAY PUBLISHING CO., Ltd., 79 and 80, Temple Chambers, Temple Avenue, E.C. 1899. T3 in PKEFACE TO SECOND EDITION. When, ten days ago, the first copy of the " Evolution of the Steam Locomotive" was ready for sale, I did not expect to be called upon to write a preface for a new edition before 240 hours had expired. The author cannot but be gratified to know that the whole of the extremely large first edition was exhausted practically upon publication, and since many would-be readers are still unsupplied, the demand for another edition is pressing. Under these circumstances but slight modifications have been made in the original text, although additional particulars and illustrations have been inserted in the new edition. The new matter relates to the locomotives of the North Staffordshire, London., Tilbury, and Southend, Great Western, and London and North Western Railways. I sincerely thank the many correspondents who, in the few days that have elapsed since the publication: of the "Evolution of the , Steam Locomotive," have so readily assured me of - their hearty appreciation of the book. rj .;! G. A. SEKON. -! January, 1899. PREFACE TO FIRST EDITION. In connection with the marvellous growth of our railway system there is nothing of so paramount importance and interest as the evolution of the locomotive steam engine. -

Operational Rail Vehicle Strategy 2019-2034 Operational Rail Vehicle Strategy 2019-2034

OPERATIONAL RAIL VEHICLE STRATEGY 2019-2034 OPERATIONAL RAIL VEHICLE STRATEGY 2019-2034 INTRODUCTION The Science Museum Group (SMG) through the National Railway Museum (NRM) owns the largest fleet of operating historic locomotives in the United Kingdom, so it’s essential that we have a strategy to ensure the most effective and efficient use of these vehicles. The NRM, Locomotion and Science & Industry Museum in Manchester (SIM) will continue to operate a select number of rail vehicles from our collection. Showing our collections in action is one of the most direct tools we have to share our key values with visitors: revealing wonder, igniting curiosity and sharing authentic stories. What’s more, our visitors expect a train ride. We need to meet that expectation whilst managing our collection in the most professional and responsible manner. A commercially viable and deliverable plan will see a core selection of operating vehicles at York and Locomotion within the maintenance capabilities of teams at those locations. These have been chosen for reasons of accessibility, affordability, income potential, attractiveness to visitors, practicality of operation and sustainable repair as well as the railway stories they reveal. We use our rail vehicles in various ways with priority always given for static display for our visitors at York and Shildon. Other ways in which we use them are: operation on museum sites; static loans to accredited museums; operating loans to heritage railways; main line operation. Our loans reach diverse audiences across the UK, making the national collection accessible to many. These vehicles are brand ambassadors for our mission of inspiring future engineers and scientists. -

Jclettersno Heading

.HERITAGE RAILWAY ASSOCIATION. Mark Garnier MP (2nd left) presents the HRA Annual Award (Large Groups) to members of the Isle of Wight Steam Railway and the Severn Valley Railway, joint winners of the award. (Photo. Gwynn Jones) SIDELINES 143 FEBRUARY 2016 WOLVERHAMPTON LOW LEVEL STATION COMES BACK TO LIFE FOR HRA AWARDS NIGHT. The Grand Station banqueting centre, once the GWR’s most northerly broad gauge station, came back to life as a busy passenger station when it hosted the Heritage Railway Association 2015 Awards Night. The HRA Awards recognise a wide range of achievements and distinctions across the entire heritage railway industry, and the awards acknowledge individuals and institutions as well as railways. The February 6th event saw the presentation of awards in eight categories. The National Railway Museum and York Theatre Royal won the Morton’s Media (Heritage Railways) Interpretation Award, for an innovative collaboration that joined theatre with live heritage steam, when the Museum acted as a temporary home for the theatre company. The Railway Magazine Annual Award for Services to Railway Preservation was won by David Woodhouse, MBE, in recognition of his remarkable 60-year heritage railways career, which began as a volunteer on the Talyllyn Railway, and took him to senior roles across the heritage railways and tourism industry. The North Yorkshire Moors Railway won the Morton’s Media (Rail Express) Modern Traction Award, for their diesel locomotive operation, which included 160 days working for their Crompton Class 25. There were two winners of the Steam Railway Magazine Award. The Great Little Trains of North Wales was the name used by the judges to describe the Bala Lake Railway, Corris Railway, Ffestiniog & Welsh Highland Railway, Talyllyn Railway, Vale of Rheidol Railway and the Welshpool & Llanfair Railway. -

Beattie Well Tank Instructions.Ai

LSWR BEATTIE WELL TANK INSTRUCTION SHEET IMPORTANT INSTRUCTIONS: PLEASE READ BEFORE USE THIS MODEL NEEDS RUNNING IN BEFORE USE History of the Beattie Well Tanks This model has been lubricated during manufacture. We suggest running in for 30 minutes in each direction. After this period, light lubrication The LSWR 0298 Class Beattie Well Tank was required a greater water capacity than the tanks may be required in the places indicated (refer to image on the right). originally built between 1863 and 1875 for use could contain, and so 31 were converted to tender We recommend B807 Dapol Dapoil Lubricant Oil available frow our on passenger services in the suburbs of London. engines between 1883 and 1887; these were Joseph Hamilton Beattie, the LSWR withdrawn between 1888 and 1898. Of the website. Please apply oil with great caution as excessive oiling will damage the mechanism and some oils can damage the plastic. If oil OIL WHERE INDICATED Mechanical Engineer, prepared a standard remainder, most were withdrawn between 1888 touches the bodyshell, wipe it off with a non-fluffy cloth immediately. No part of the motor requires design of 2-4-0 well tank; and the LSWR began and 1899, but six were modernised between 1889 lubrication. DO NOT operate the model on track laid onto carpet as dust and fibres will impair the mechanism. to take delivery of these in 1863. The new and 1894 for use on branch lines such as those to Due to its short wheelbase and low gearing, this model is not suitable or use at low speed over sectional track design eventually totalled 85 locomotives; most Exmouth and Sidmouth. -

Railways As World Heritage Sites

Occasional Papers for the World Heritage Convention RAILWAYS AS WORLD HERITAGE SITES Anthony Coulls with contributions by Colin Divall and Robert Lee International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) 1999 Notes • Anthony Coulls was employed at the Institute of Railway Studies, National Railway Museum, York YO26 4XJ, UK, to prepare this study. • ICOMOS is deeply grateful to the Government of Austria for the generous grant that made this study possible. Published by: ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) 49-51 Rue de la Fédération F-75015 Paris France Telephone + 33 1 45 67 67 70 Fax + 33 1 45 66 06 22 e-mail [email protected] © ICOMOS 1999 Contents Railways – an historical introduction 1 Railways as World Heritage sites – some theoretical and practical considerations 5 The proposed criteria for internationally significant railways 8 The criteria in practice – some railways of note 12 Case 1: The Moscow Underground 12 Case 2: The Semmering Pass, Austria 13 Case 3: The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, United States of America 14 Case 4: The Great Zig Zag, Australia 15 Case 5: The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, India 17 Case 6: The Liverpool & Manchester Railway, United Kingdom 19 Case 7: The Great Western Railway, United Kingdom 22 Case 8: The Shinkansen, Japan 23 Conclusion 24 Acknowledgements 25 Select bibliography 26 Appendix – Members of the Advisory Committee and Correspondents 29 Railways – an historical introduction he possibility of designating industrial places as World Heritage Sites has always been Timplicit in the World Heritage Convention but it is only recently that systematic attention has been given to the task of identifying worthy locations. -

The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway

The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. The 1825 Stockton & Darlington Railway: Historic Environment Audit Volume 1: Significance & Management October 2016 Archaeo-Environment for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton on Tees Borough Council. Archaeo-Environment Ltd for Durham County Council, Darlington Borough Council and Stockton Borough Council 1 The 1825 S&DR: Preparing for 2025; Significance & Management. Executive Summary The ‘greatest idea of modern times’ (Jeans 1974, 74). This report arises from a project jointly commissioned by the three local authorities of Darlington Borough Council, Durham County Council and Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council which have within their boundaries the remains of the Stockton & Darlington Railway (S&DR) which was formally opened on the 27th September 1825. The report identifies why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and sets out its significance and unique selling point. This builds upon the work already undertaken as part of the Friends of Stockton and Darlington Railway Conference in June 2015 and in particular the paper given by Andy Guy on the significance of the 1825 S&DR line (Guy 2015). This report provides an action plan and makes recommendations for the conservation, interpretation and management of this world class heritage so that it can take centre stage in a programme of heritage led economic and social regeneration by 2025 and the bicentenary of the opening of the line. More specifically, the brief for this Heritage Trackbed Audit comprised a number of distinct outputs and the results are summarised as follows: A. Identify why the S&DR was important in the history of railways and clearly articulate its significance and unique selling point. -

Hackworth Family Archive

Hackworth Family Archive A cataloguing project made possible by the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives Science Museum Group 1 Description of Entire Archive: HACK (fonds level description) Title Hackworth Family Archive Fonds reference code GB 0756 HACK Dates 1810’s-1980’s Extent & Medium of the unit of the 1036 letters with accompanying letters and associated documents, 151 pieces of printed material and printed images, unit of description 13 volumes, 6 drawings, 4 large items Name of creator s Hackworth Family Administrative/Biographical Hackworth, Timothy (b 1786 – d 1850), Railway Engineer was an early railway pioneer who worked for the Stockton History and Darlington Railway Company and had his own engineering works Soho Works, in Shildon, County Durham. He married and had eight children and was a converted Wesleyan Methodist. He manufactured and designed locomotives and other engines and worked with other significant railway individuals of the time, for example George and Robert Stephenson. He was responsible for manufacturing the first locomotive for Russia and British North America. It has been debated historically up to the present day whether Hackworth gained enough recognition for his work. Proponents of Hackworth have suggested that he invented of the ‘blast pipe’ which led to the success of locomotives over other forms of rail transport. His sons other relatives went on to be engineers. His eldest son, John Wesley Hackworth did a lot of work to promote his fathers memory after he died. His daughters, friends, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and ancestors to this day have worked to try and gain him a prominent place in railway history.