The Fables of La Fontaine [Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES ILLUSTRATED BY HAROLD YATES THE OLDEG N GALLEY SERIES OF JUNIOR CLASSICS AESOP’S FABLES Retold, by ARTHUR B. ALLEN Illustrated by Harold Yates LONDON GOLDEN GALLEY PRESS LIMITED First Published in this Edition 1948 R.8022 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Text by Adelphi Associated Press, London, 17.1. Colour Plates by Perry Colourprint Ltd., London, S.17.15. CONTENTS Introduction I. The Cock and the Jewel II. The Wolf and the Lamb III. The Frogs who wanted a King IV. The Vain Jackdaw V. The Dog and the Shadow VI. The Lion and the Other Beasts VII. The Wolf and the Crane VIII. The Stag and the Water IX. The Fox and the Crow X. The Two Bitches XL The Proud Frog XII. The Fox and the Stork XIII. The Eagle and the Fox XIV. The Boar and the Ass XV. The Frogs and the Fighting Bulls XVI. The Kite and the Pigeons XVII. The Lark and Her Young Ones XVIII. The Stag in the Ox-stall XIX. The Dog and the Wolf XX. The Lamb brought up by a Goat XXL The Peacock’s Complaint XXII. The Fox and the Grapes XXIII. The Viper and the File XXIV. The Fox and the Goat XXV. The Countryman and the Snake XXVI. The Mountains in Labour XXVII. The Ant and the Fly XXVIII. The Old Hound XXIX. The Sick Kite XXX. The Hares and the Frogs XXXI. The Lion and the Mouse XXXII. The Fatal Marriage XXXIII. The Wood and the Clown XXXIV. The Horse and the Stag XXXV. -

42 the Fox and the Sick Lion -- 43 the Young Thief and His Mother - 44 the Travelers and the Bear - - 45 the Thrush and the Swallow - - 47 the Lioness and the Fox

Æ S OP’S AB LES 'HE HOME LIBRARY ■f BURT COMPANY. N V CONTENTS. pm Editor’s Preface - - 3 Life of Æsop - • 9 The Fox And the Crow . • - 13 The Man and His Two Wives - 14 The Two Frogs - - - 16 The Stag Looking into the Pool - - 16 Jupiter and the Camel - - - 16 The Lion Hunting with other Beasts - 16 The Cock and the Jewel - - - 17 The Dog and his Shadow - 17 The Wolf and the Lamb - - - 18 The Peacock and Juno - - 18 The Ant and the Fly - - - 20 The Stag in the Ox-Stall - 21 The Cat and the Mice - - - 22 The Hawk and the Nightingale - 23 The Belly and the Members - - 23 The Bald Knight - - 24 The Kite and the Pigeons - - 24 The Mischievous Dog - - 25 The Frog who Wished to be as Big as an Ox - 25 The Fatal Courtship - - 27 The Bald Man and the Fly - - 27 The Frogs and the Fighting Bulls - - 28 The Man and the Lion - - - 28 The Brother and Sister - - 29 The Countryman and the Snake - - 30 The Wind and the Sun - - 31 iv CONTENTS. PAQE The Boasting Traveler • -•- 31 The Spendthrift and the Swallow ---- 32 The Leopard and the Fox - -- 32 The Jackdaw and the Pigeons - -• 33 The Sick Kite - 33 The Lion and the Monse - - 34 The Wolf and the Crane - - - • 35 The Lion in Love - - - 35 Caesar and the Slave - - 37 The Collier and the Fuller - - 37 The Hares and the Frogs - - • 38 The Wanton Calf - - 39 The Eagle, the Cat, and the Sow -- 40 The Sow and the Cat - 41 The Wolf, the Fox, and the Ape -- 41 The Lion, the Ass, and the Fox - 42 The Fox and the Sick Lion -- 43 The Young Thief and his Mother - 44 The Travelers and the Bear - - 45 The Thrush and the Swallow - - 47 The Lioness and the Fox . -

Aesop's Fables

Masterpiece Library U) 13-444/52.95 AESOP’S FABLES COMPLETE AND UNABRIDGED AFABLESESOP’S Masterpiece Library MAGNUM BOOKS NEW YORK masterpiece library AESOP’S FABLES Special contents of this edition copyright © 1968 by Lancer Books, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the U.SA. CONTENTS The Fox and the Crow 11 The Gardener and His Dog 13 The Milkmaid and Her Pail 14 The Ant and the Grasshopper 16 The Mice in Council 17 The Fox and the Grapes 18 The Fox and the Goat 19 The Ass Carrying Salt 20 The Gnat and the Bull 22 The Hare with Many Friends 24 The Hare and the Hound 25 The House Dog and the Wolf 26 The Goose with the Golden Eggs 28 The Fox and the Hedgehog 29 The Horse and the Stag 31 The Lion and the Bulls 32 The Goatherd and the Goats 33 5 Androcles and the Lion 34 The Hare and the Tortoise 36 The Ant and the Dove 38 The One-Eyed Doe 39 The Ass and His Masters 40 The Lion and the Dolphin 42 The Ass’s Shadow 43 The Ass Eating Thistles 44 The Hawk and the Pigeons 45 The Belly and the Other Members 47 The Frogs Desiring a King 49 The Cat and the Mice 51 The Miller, His Son, and Their Donkey 53 The Ass, the Cock, and the Lion 55 The Hen and the Fox 57 The Lion and the Goat 58 The Fox and the Lion 59 The Crow and the Pitcher 60 The Boasting Traveler 61 The Eagle, the Wildcat, and the Sow 62 The Ass and the Grasshopper 64 The Heifer and the Ox 65 The Fox and the Stork 67 The Farmer and the Nightingale 69 The Ass and the Lap Dog 71 Jupiter and the Bee 73 The Horse and the Groom 75 The Mischievous Dog 76 The Blind Man and the Whelp 77 The -

Krilòff's Fables;

5 5 (7 V 3 ^ '^\^^ aofcaiifo% 5> . V f ^^Aavaanii^ ^^Aavnaiiiv^ ^MEUNIVERS/A >:101% ^^•UBRARY6>/r, : be- _ ^ '^.i/OJnVDJO'^ ^^WEUNIVERS/^ ^lOSANCElfj> zmoR^y <ril30HVS01^ %a3AINnJl\V "^OWSiUW^ ^AOJITVDJO^ ^AOJITVD-JO^ ^^ ^OFCAIIFO/?^ AWEUNIVERva CO -< ^c'AHvaan^' %133NVS01^^ AWEUNIVERSy^ ANGELA* /:^ =6 <=- vN- , \ME UNIVERJ/A v>;lOSANCElfj>. ^OFCAll FO/?^ ^OFCAIIFOI?^ ^OFCAIIFO;?^ -I^EUNIVERSyA .v pa ^J'JiaQKvso^^^ AWEl)NIVERy/A v>:lOSANCEl£r;x §1 ir-U b. s -< J' JNVSOl^ aWEUNIVERSZ/v ^lOSANCElfx^ ^OFCAllFOff^ WcOfC <rinONVS01^ %a3AINft3W^ -^^^•UBRARYO^ 5i\EUNIVER% ^^HOiim JO 4^OFCAllF0ff^ ^OFCAIIFO;?^ 5MEUNIVERS/// va'diii^^^' ^<?AavHani jjimm'^ .\WEUNIVER% ^^10SANCEI%^ 4,>MUBRARYQ^^ >i V ^ <5 , ,\WEUNIVERS-//, vvlOSANCElfj-;> ^OFCALIf : KRILOFF'S FABLES Translated from the Russian into English in the original metres BY FILLINGHAM COXWELL, m.d. Author of Chronicles of Man, Through Russia in War Time WITH 4 PIRATES LONDON KEGAN PAUL. TRENCH, TRUBNER & Co., Ltd. NEW YORK : E. P. BUTTON & Co. A Printed Great Britain by BovvERiNG & Co., St. Andrev.'s Printing Works, George Street, Plymouth. PREFACE RILOFF is such a remarkable figure in Russian literature, and his Fables are so interesting and admirable that I have ventured to render eighty-six of them into English. No prose translation can do this poet-fabulist justice, but a rendering in metrical fonns, corresponding with his own, may give readers some idea of his merits. If it be recalled that the source of most fables is hidden in the mists of antiquity, then Kriloff 's originality can scarcely fail to be a recommendation. He wrote, in all, 201 fables and there seems little doubt that, in four-fifths of them, he was not indebted to anyone. -

Aesop's Fables

aesop's fables ILLUSTRATED BY FKIT2^ KKEDEL ILLUSTr a TED JUNIo r LIBraru / aesop's fa b le s Illustrated Junior Library WITH DRAWINGS BY Fritz Kredel GROSSET Sc DUNLAP £•» Publishers The special contents of this edition are copyright © 1947 by Grosset & Dunlap, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Published simultaneously in Canada. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 47-31077 ISBN: 0-448-11003-2 1987 P r in t in g THE DOC IN THE MANCER 1 THE WOLF IN SHEEP’S CLOTHING 2 MERCURY AND THE WOODMAN 3 THE FOX AND THE CROW 5 THE CARDENER AND HIS DOC 7 THE ANCLER AND THE LITTLE FISH 8 THE FAWN AND HER MOTHER 9 THE MILKMAID AND HER PAIL 10 THE ANT AND THE CRASSHOPPER 12 THE MICE IN COUNCIL 13 THE GNAT AND THE BULL 14 THE FOX AND THE GOAT 15 THE ASS CARRYING SALT 16 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 18 THE HARE WITH MANY FRIENDS 19 THE HARE AND THE HOUND 21 THE HOUSE DOC AND THE WOLF 22 THE GOOSE WITH THE GOLDEN ECCS 25 THE FOX AND THE HEDCEHOC 26 THE HORSE AND THE STAC 28 THE LION AND THE BULLS 30 THE GOATHERD AND THE GOATS 31 THE HARE AND THE TORTOISE 32 ANDROCLES AND THE LION 34 THE ANT AND THE DOVE 36 THE ONE-EYED DOE 37 THE ASS AND HIS MASTERS 38 THE LION AND THE DOLPHIN 39 THE ASSS SHADOW 41 THE ASS EATING THISTLES 42 THE HAWK AND THE PICEONS 44 THE BELLY AND THE OTHER MEMBERS 46 THE FROGS DESIRINC A KING 47 THE HEN AND THE FOX 49 THE CAT AND THE MICE 51 THE MILLER. -

In the Afternoon

AESOP In the Afternoon ALBERT CULLUM AESOP In the Afternoon Albert Cullum CITATION PRESS N EW Y O R K 1972 Other Citation Press Books by Albert Cullurn PUSH BACK THE DESKS SHAKE HANDS WITH SHAKESPEARE: Eight Plays for Elementary Schools GREEK TEARS AND ROMAN LAUGHTER: Len I ragedies and hive Comedies for Schools To a back porch of summer memories... G r a t e f u l acknowledgment is m ade to N o rm a M il l a y E l l is fo r p e r m ission to r e p r in t “ S econd F ig ” by E dna St . V in c e n t M i i .l a y fro m COLLECTED POEMS, H a r p e r & R ow . C o p y r ig h t 1922, 1950 by E dna St . V in c e n t M i l l a y . C o p y r ig h t © 1972 b y Sc h o la stic M a g a z in e s, I n c . A l l rig h ts reser v ed . P u blish ed by C ita tio n P ress, L ib r a r y and T rade D iv isio n , Sc h o la stic M a g a z in e s, I n c ., E d ito ria l O f f ic e : 50 W est 44 St r e e t , N ew Y o r k , N ew Y ork 10036. -

Aesop's and Other Fables

Aesop’s and other Fables Æsop’ s and other Fables AN ANTHOLOGY INTRODUCTION BY ERNEST RHYS POSTSCRIPT BY ROGER LANCELYN GREEN Dent London Melbourne Toronto EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY Dutton New York © Postscript, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1971 AU rights reserved Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford, Surrey for J. M. DENT & SONS LTD Aldine House, 33 Welbeck Street, London This edition was first published in Every matt’s Library in 19 13 Last reprinted 1980 Published in the USA by arrangement with J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd No 657 Hardback isbn o 460 00657 6 No 1657 Paperback isbn o 460 01657 1 CONTENTS PAGE A vision o f Æ sop Robert Henryson , . * I L FABLES FROM CAXTON’S ÆSOP The Fox and the Grapes. • • 5 The Rat and the Frog 0 0 5 The W olf and the Skull . • 0 0 5 The Lion and the Cow, the Goat and the Sheep • 0 0 6 The Pilgrim and the Sword • • 0 6 The Oak and the Reed . 0 6 The Fox and the Cock . , . 0 7 The Fisher ..... 0 7 The He-Goat and the W olf . • •• 0 8 The Bald Man and the Fly . • 0 0 8 The Fox and the Thom Bush .... • t • 9 II. FABLES FROM JAMES’S ÆSOP The Bowman and the Lion . 0 0 9 The W olf and the Crane . , 0 0 IO The Boy and the Scorpion . 0 0 IO The Fox and the Goat . • 0 0 IO The Widow and the Hen . 0 0 0 0 II The Vain Jackdaw ... -

Aesop's Fables

Study Guide prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-in-Residence Aesop’s Fables Book & Lyrics by Catherine Bush Music by Ben Mackel *Especially for Grades K-8 By the Barter Players, Barter Theatre, Spring 2012 (NOTE: standards listed below are for both reading Aesop’s Fables and seeing a performance.) Virginia SOLs English – K.1, K.8, 1.1, 1.9, 2.1, 2.8, 3.1, 3.4, 3.5, 4.4, 5.5, 6.4, 7.5, 8.5 Theatre Arts – M.6, M.8, M.9, M.13, M.14 Music – K.11, K.12, 1.11, 1.12, 2.10, 2.11, 3.14, 3.15, 4.14, 4.15, 5.12, 5.13, MS.7, MS.8 Tennessee TCAPS English/Language Arts – K.1.02, K.1.07, K.1.13, 1.1.01, 1.1.02, 1.1.07, 1.1.13, 2.1.01, 2.1.02, 2.1.07, 2.1.13, 3.1.01, 3.1.02, 3.1.07, 3.1.13, 4.1.01, 4.1.06, 4.1.12, 5.1.01, 5.1.06, 5.1.12, 6.1.06, 6.1.12, 6.1.13, 7.1.12, 7.1.13, 8.1.12, 8.1.13 Music – K.6.0, 1.8.0, 2.8.1, 3.8.0, 4.8.0, 5.8.0 Music 6th-8th – 8.0 Theatre Arts – Level I, II, III Theatre 6th-8th Grade – 6.0, 7.0, 8.0 North Carolina SCOS Theatre Arts – K.7.05, K.8.03, 1.7.05, 1.8.04, 2.7.01, 2.7.05, 2.8.04, 2.8.06, 3.7.05, 3.7.07, 3.8.01, 3.8.04, 3.8.05, 4.7.06, 4.7.07, 4.7.09, 4.8.01, 4.8.04, 5.7.07, 5.7.09, 5.8.04, 6.7.01, 6.7.03, 6.7.07, 7.7.01, 7.7.03, 8.7.01, 8.7.04, 8.7.06 Music – K.7.02, K.8.01, 1.7.02, 1.8.01, 2.7.03, 2.8.01, 3.7.03, 3.8.02, 4.7.03, 4.8.02, 5.7.03, 5.8.02, 6.7.04, 6.8.01, 7.7.04, 7.8.03, 8.7.04, 8.8.01 English Language Arts – K.2.02, 1.2.02, 2.3.02, 2.3.04, 3.3.01, 4.3.01, 5.3.01, 6.1.02, 7.1.02, 8.1.02 Setting Various locations in ancient Greece, including the House of Xanthus, a wealthy landowner, the fields and forest surrounding his home and the arena in which the local games are held. -

Aesop's Fables

451-CE2565 ☆ (CANADA $ 5.99) ☆ U.S. $4.95 AESOP’S FABLES Including: The Fox and the Grapes The Ants and the Grasshopper The Country Mouse and the City Mouse ...and 200 other famous fables SELECTED AND ADAPTED BY JACK ZIPES AESOP'S FABLES Selected and Adapted by Jack Zipes A SIGNET CLASSIC SIGNET CLASSIC Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York. New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd. Ringwood. Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd. 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd. Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex. England Published by Signet Classic, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. First Signet Classic Printing, October. 1992 10 987654321 Copyright © Jack Zipes. 1992 All rights reserved REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 92-60921 Printed in the United States of America BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MAR KETING DIVISION. PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC.. 375 HUDSON STREET. NEW YORK. NEW YORK 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Contents -

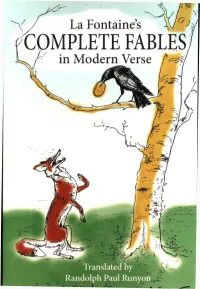

COMPLETE FABLES Kh

'y La Fontaines \wQ COMPLETE FABLES Kh Translated by Randolphr Paul Runyon' ,f/ La Fontaines, -AV COMPLETE FABLES in Modern Verse /■ Translated by Randolph Paul Runyon For Elizabeth Two fables in Book 12, “Consoling the Widow” and “On a Mission from Hell,” taken from La Fontaine’s Complete Tales in Verse: An Illustrated and Annotated Translation ©2009 Jean de La Fontaine. Edited and translated by Randolph Paul Runyon, printed here by permission of McFarland & Com pany, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson, NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. (In the McFarland book, they appear as “The Ephesian Matron” and “Belphegor.”) Cover design by Stacey Castle Design, staceycastle.com Interior pages design/layout by Elizabeth S. Runyon Printed by CreateSpace, An Amazon.com Company Available on Kindle Contact Randolph Paul Runyon: [email protected] Contents Translator’s Preface.................................................................................. 2 To Monseigneur the Dauphin...............................................................6 THE FABLES Book 1 The Cicada and the Ant (1, 1)................................................................. 7 The Crow and the Fox (1,2)....................................................................8 The Frog Who Wanted to Be as Big as a Bull (1, 3)............................ 8 The Two Mules (1, 4)..............................................................................11 The Wolf and the Dog (1, 5)..................................................................12 The Lion’s Share (1,6).......................................................................... -

77694-2134.Pdf

Æ S O P’S FABLES ARRANGED FOR CHILDREN'BY NELLIE PERKINS DOBBS ILLUSTRATED BY LYDIA GRANT TOPEKA, KANSAS I CKANE A: COMPANY, PUBLISHERS 1904 Copyright 1904, By Crane & Company, Topeka, Kansas. CONTENTS. Preface ...................................................................................... P a g e7 Life of Æsop . ....................................................................... 9 The Cock and the Jewel............................................................ IB The Dove and the Ant............................................................. U The Frogs and the Boys.......................................................... 15 The Ants and the Grasshopper........i.................................... 16 The Hen and the F ox .............................................................. 17 The Old Woman and her Maids............................................ 19 The Ass Carrying an Idol........................................................ 20 The Fox and the Crow............... ............................................. 21 The Seaside Travelers..........................................................» • 2B The Dog and the Hare.............................................................. 24 The Hares and the Frogs in a Storm.................................... 25 The Country Mouse and the City Mouse................................ 27 The Fox and the Grapes.......................................................... BO The Goose and the Golden Egg.............................................. B1 The Miller, His Son, and -

The Fables of La Fontaine

The Fables of La Fontaine Jean de La Fontaine The Fables of La Fontaine Table of Contents The Fables of La Fontaine........................................................................................................................................1 Jean de La Fontaine........................................................................................................................................2 Translated From The French By Elizur Wright..........................................................................................................8 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................9 THE DOG AND CAT..................................................................................................................................11 THE GOLDEN PITCHER...........................................................................................................................12 PARTY STRIFE..........................................................................................................................................14 THE CAT AND THE THRUSH.................................................................................................................15 BOOK I.....................................................................................................................................................................30 I.—THE GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANT.[1].........................................................................................31