Krilòff's Fables;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES ILLUSTRATED BY HAROLD YATES THE OLDEG N GALLEY SERIES OF JUNIOR CLASSICS AESOP’S FABLES Retold, by ARTHUR B. ALLEN Illustrated by Harold Yates LONDON GOLDEN GALLEY PRESS LIMITED First Published in this Edition 1948 R.8022 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN Text by Adelphi Associated Press, London, 17.1. Colour Plates by Perry Colourprint Ltd., London, S.17.15. CONTENTS Introduction I. The Cock and the Jewel II. The Wolf and the Lamb III. The Frogs who wanted a King IV. The Vain Jackdaw V. The Dog and the Shadow VI. The Lion and the Other Beasts VII. The Wolf and the Crane VIII. The Stag and the Water IX. The Fox and the Crow X. The Two Bitches XL The Proud Frog XII. The Fox and the Stork XIII. The Eagle and the Fox XIV. The Boar and the Ass XV. The Frogs and the Fighting Bulls XVI. The Kite and the Pigeons XVII. The Lark and Her Young Ones XVIII. The Stag in the Ox-stall XIX. The Dog and the Wolf XX. The Lamb brought up by a Goat XXL The Peacock’s Complaint XXII. The Fox and the Grapes XXIII. The Viper and the File XXIV. The Fox and the Goat XXV. The Countryman and the Snake XXVI. The Mountains in Labour XXVII. The Ant and the Fly XXVIII. The Old Hound XXIX. The Sick Kite XXX. The Hares and the Frogs XXXI. The Lion and the Mouse XXXII. The Fatal Marriage XXXIII. The Wood and the Clown XXXIV. The Horse and the Stag XXXV. -

017 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books soldier could see through the window how the peopL were hurrying out of the town to see him hanged —P«ge 354 THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Folk-Lore and Fable iEsop • Grimm Andersen With Introductions and No/« Volume 17 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. *. A. CONTENTS ^SOP'S FABLES— PAGE THE COCK AND THE PEARL n THE WOLF AND THE LAMB n THE DOG AND THE SHADOW 12 THE LION'S SHARE 12 THE WOLF AND THE CRANE 12 THE MAN AND THE SERPENT 13 THE TOWN MOUSE AND THE COUNTRY MOUSE 13 THE FOX AND THE CROW 14 THE SICK LION 14 THE ASS AND THE LAPDOG 15 THE LION AND THE MOUSE 15 THE SWALLOW AND THE OTHER BIRDS 16 THE FROGS DESIRING A KING 16 THE MOUNTAINS IN LABOUR 17 THE HARES AND THE FROGS 17 THE WOLF AND THE KID 18 THE WOODMAN AND THE SERPENT 18 THE BALD MAN AND THE FLY 18 THE FOX AND THE STORK 19 THE FOX AND THE MASK 19 THE JAY AND THE PEACOCK 19 THE FROG AND THE OX 20 ANDROCLES 20 THE BAT, THE BIRDS, AND THE BEASTS 21 THE HART AND THE HUNTER 21 THE SERPENT AND THE FILE 22 THE MAN AND THE WOOD 22 THE DOG AND THE WOLF 22 THE BELLY AND THE MEMBERS 23 THE HART IN THE OX-STALL 23 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 24 THE HORSE, HUNTER, AND STAG 24 THE PEACOCK AND JUNO 24 THE FOX AND THE LION 25 1 2 CONTENTS PAGE THE LION AND THE STATUE 25 THE ANT AND THE GRASSHOPPER 25 THE TREE AND THE REED 26 THE FOX AND THE CAT 26 THE WOLF IN SHEEP'S CLOTHING 27 THE DOG IN THE MANGER 27 THE MAN AND THE WOODEN GOD 27 THE FISHER 27 THE SHEPHERD'S -

Aesop's Fables

Masterpiece Library U) 13-444/52.95 AESOP’S FABLES COMPLETE AND UNABRIDGED AFABLESESOP’S Masterpiece Library MAGNUM BOOKS NEW YORK masterpiece library AESOP’S FABLES Special contents of this edition copyright © 1968 by Lancer Books, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the U.SA. CONTENTS The Fox and the Crow 11 The Gardener and His Dog 13 The Milkmaid and Her Pail 14 The Ant and the Grasshopper 16 The Mice in Council 17 The Fox and the Grapes 18 The Fox and the Goat 19 The Ass Carrying Salt 20 The Gnat and the Bull 22 The Hare with Many Friends 24 The Hare and the Hound 25 The House Dog and the Wolf 26 The Goose with the Golden Eggs 28 The Fox and the Hedgehog 29 The Horse and the Stag 31 The Lion and the Bulls 32 The Goatherd and the Goats 33 5 Androcles and the Lion 34 The Hare and the Tortoise 36 The Ant and the Dove 38 The One-Eyed Doe 39 The Ass and His Masters 40 The Lion and the Dolphin 42 The Ass’s Shadow 43 The Ass Eating Thistles 44 The Hawk and the Pigeons 45 The Belly and the Other Members 47 The Frogs Desiring a King 49 The Cat and the Mice 51 The Miller, His Son, and Their Donkey 53 The Ass, the Cock, and the Lion 55 The Hen and the Fox 57 The Lion and the Goat 58 The Fox and the Lion 59 The Crow and the Pitcher 60 The Boasting Traveler 61 The Eagle, the Wildcat, and the Sow 62 The Ass and the Grasshopper 64 The Heifer and the Ox 65 The Fox and the Stork 67 The Farmer and the Nightingale 69 The Ass and the Lap Dog 71 Jupiter and the Bee 73 The Horse and the Groom 75 The Mischievous Dog 76 The Blind Man and the Whelp 77 The -

Aesop's Fables

1-21 22-42 The Cock and the Pearl The Frog and the Ox The Wolf and the Lamb Androcles The Dog and the Shadow The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts The Lion's Share The Hart and the Hunter The Wolf and the Crane The Serpent and the File The Man and the Serpent The Man and the Wood The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse The Dog and the Wolf The Fox and the Crow The Belly and the Members The Sick Lion The Hart in the Ox-Stall The Ass and the Lapdog The Fox and the Grapes The Lion and the Mouse The Horse, Hunter, and Stag The Swallow and the Other Birds The Peacock and Juno The Frogs Desiring a King The Fox and the Lion The Mountains in Labour The Lion and the Statue The Hares and the Frogs The Ant and the Grasshopper The Wolf and the Kid The Tree and the Reed The Woodman and the Serpent The Fox and the Cat The Bald Man and the Fly The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing The Fox and the Stork The Dog in the Manger The Fox and the Mask The Man and the Wooden God The Jay and the Peacock The Fisher 43-62 63-82 The Shepherd's Boy The Miser and His Gold The Young Thief and His Mother The Fox and the Mosquitoes The Man and His Two Wives The Fox Without a Tail The Nurse and the Wolf The One-Eyed Doe The Tortoise and the Birds Belling the Cat The Two Crabs The Hare and the Tortoise The Ass in the Lion's Skin The Old Man and Death The Two Fellows and the Bear The Hare With Many Friends The Two Pots The Lion in Love The Four Oxen and the Lion The Bundle of Sticks The Fisher and the Little Fish The Lion, the Fox, and the Beasts Avaricious and Envious The Ass's Brains -

Aesop's Fables, However, Includes a Microsoft Word Template File for New Question Pages and for Glos- Sary Pages

1 æsop’s fables Click here to jump to the Table of Contents 2 Copyright 1993 by Adobe Press, Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. The text of Aesop’s Fables is public domain. Other text sections of this book are copyrighted. Any reproduction of this electronic work beyond a personal use level, or the display of this work for public or profit consumption or view- ing, requires prior permission from the publisher. This work is furnished for informational use only and should not be construed as a commitment of any kind by Adobe Systems Incorporated. The moral or ethical opinions of this work do not necessarily reflect those of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Systems Incorporated assumes no responsibilities for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in this work. The software and typefaces mentioned on this page are furnished under license and may only be used in accordance with the terms of such license. This work was electronically mastered using Adobe Acrobat software. The original composition of this work was created using FrameMaker. Illustrations were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop. The display text is Herculanum. Adobe, the Adobe Press logo, Adobe Acrobat, and Adobe Photoshop are trade- marks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain juris- dictions. 3 Contents • Copyright • How to use this book • Introduction • List of fables by title • Aesop’s Fables • Index of titles • Index of morals • How to create your own glossary and question pages • How to print and make your own book • Fable questions Click any line to jump to that section 4 How to use this book This book contains several sections. -

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES BY AESOP © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2008 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. -

Aesop's and Other Fables

Aesop’s and other Fables Æsop’ s and other Fables AN ANTHOLOGY INTRODUCTION BY ERNEST RHYS POSTSCRIPT BY ROGER LANCELYN GREEN Dent London Melbourne Toronto EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY Dutton New York © Postscript, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1971 AU rights reserved Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford, Surrey for J. M. DENT & SONS LTD Aldine House, 33 Welbeck Street, London This edition was first published in Every matt’s Library in 19 13 Last reprinted 1980 Published in the USA by arrangement with J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd No 657 Hardback isbn o 460 00657 6 No 1657 Paperback isbn o 460 01657 1 CONTENTS PAGE A vision o f Æ sop Robert Henryson , . * I L FABLES FROM CAXTON’S ÆSOP The Fox and the Grapes. • • 5 The Rat and the Frog 0 0 5 The W olf and the Skull . • 0 0 5 The Lion and the Cow, the Goat and the Sheep • 0 0 6 The Pilgrim and the Sword • • 0 6 The Oak and the Reed . 0 6 The Fox and the Cock . , . 0 7 The Fisher ..... 0 7 The He-Goat and the W olf . • •• 0 8 The Bald Man and the Fly . • 0 0 8 The Fox and the Thom Bush .... • t • 9 II. FABLES FROM JAMES’S ÆSOP The Bowman and the Lion . 0 0 9 The W olf and the Crane . , 0 0 IO The Boy and the Scorpion . 0 0 IO The Fox and the Goat . • 0 0 IO The Widow and the Hen . 0 0 0 0 II The Vain Jackdaw ... -

Aesop's Fables

Study Guide prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-in-Residence Aesop’s Fables Book & Lyrics by Catherine Bush Music by Ben Mackel *Especially for Grades K-8 By the Barter Players, Barter Theatre, Spring 2012 (NOTE: standards listed below are for both reading Aesop’s Fables and seeing a performance.) Virginia SOLs English – K.1, K.8, 1.1, 1.9, 2.1, 2.8, 3.1, 3.4, 3.5, 4.4, 5.5, 6.4, 7.5, 8.5 Theatre Arts – M.6, M.8, M.9, M.13, M.14 Music – K.11, K.12, 1.11, 1.12, 2.10, 2.11, 3.14, 3.15, 4.14, 4.15, 5.12, 5.13, MS.7, MS.8 Tennessee TCAPS English/Language Arts – K.1.02, K.1.07, K.1.13, 1.1.01, 1.1.02, 1.1.07, 1.1.13, 2.1.01, 2.1.02, 2.1.07, 2.1.13, 3.1.01, 3.1.02, 3.1.07, 3.1.13, 4.1.01, 4.1.06, 4.1.12, 5.1.01, 5.1.06, 5.1.12, 6.1.06, 6.1.12, 6.1.13, 7.1.12, 7.1.13, 8.1.12, 8.1.13 Music – K.6.0, 1.8.0, 2.8.1, 3.8.0, 4.8.0, 5.8.0 Music 6th-8th – 8.0 Theatre Arts – Level I, II, III Theatre 6th-8th Grade – 6.0, 7.0, 8.0 North Carolina SCOS Theatre Arts – K.7.05, K.8.03, 1.7.05, 1.8.04, 2.7.01, 2.7.05, 2.8.04, 2.8.06, 3.7.05, 3.7.07, 3.8.01, 3.8.04, 3.8.05, 4.7.06, 4.7.07, 4.7.09, 4.8.01, 4.8.04, 5.7.07, 5.7.09, 5.8.04, 6.7.01, 6.7.03, 6.7.07, 7.7.01, 7.7.03, 8.7.01, 8.7.04, 8.7.06 Music – K.7.02, K.8.01, 1.7.02, 1.8.01, 2.7.03, 2.8.01, 3.7.03, 3.8.02, 4.7.03, 4.8.02, 5.7.03, 5.8.02, 6.7.04, 6.8.01, 7.7.04, 7.8.03, 8.7.04, 8.8.01 English Language Arts – K.2.02, 1.2.02, 2.3.02, 2.3.04, 3.3.01, 4.3.01, 5.3.01, 6.1.02, 7.1.02, 8.1.02 Setting Various locations in ancient Greece, including the House of Xanthus, a wealthy landowner, the fields and forest surrounding his home and the arena in which the local games are held. -

Aesop's Fables

451-CE2565 ☆ (CANADA $ 5.99) ☆ U.S. $4.95 AESOP’S FABLES Including: The Fox and the Grapes The Ants and the Grasshopper The Country Mouse and the City Mouse ...and 200 other famous fables SELECTED AND ADAPTED BY JACK ZIPES AESOP'S FABLES Selected and Adapted by Jack Zipes A SIGNET CLASSIC SIGNET CLASSIC Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York. New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd. Ringwood. Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd. 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd. Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex. England Published by Signet Classic, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. First Signet Classic Printing, October. 1992 10 987654321 Copyright © Jack Zipes. 1992 All rights reserved REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 92-60921 Printed in the United States of America BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MAR KETING DIVISION. PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC.. 375 HUDSON STREET. NEW YORK. NEW YORK 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Contents -

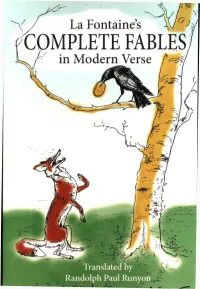

COMPLETE FABLES Kh

'y La Fontaines \wQ COMPLETE FABLES Kh Translated by Randolphr Paul Runyon' ,f/ La Fontaines, -AV COMPLETE FABLES in Modern Verse /■ Translated by Randolph Paul Runyon For Elizabeth Two fables in Book 12, “Consoling the Widow” and “On a Mission from Hell,” taken from La Fontaine’s Complete Tales in Verse: An Illustrated and Annotated Translation ©2009 Jean de La Fontaine. Edited and translated by Randolph Paul Runyon, printed here by permission of McFarland & Com pany, Inc., Box 611, Jefferson, NC 28640. www.mcfarlandpub.com. (In the McFarland book, they appear as “The Ephesian Matron” and “Belphegor.”) Cover design by Stacey Castle Design, staceycastle.com Interior pages design/layout by Elizabeth S. Runyon Printed by CreateSpace, An Amazon.com Company Available on Kindle Contact Randolph Paul Runyon: [email protected] Contents Translator’s Preface.................................................................................. 2 To Monseigneur the Dauphin...............................................................6 THE FABLES Book 1 The Cicada and the Ant (1, 1)................................................................. 7 The Crow and the Fox (1,2)....................................................................8 The Frog Who Wanted to Be as Big as a Bull (1, 3)............................ 8 The Two Mules (1, 4)..............................................................................11 The Wolf and the Dog (1, 5)..................................................................12 The Lion’s Share (1,6).......................................................................... -

Chanticleer and the Fox Ebook

CHANTICLEER AND THE FOX PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoffrey Chaucer,Barbara Cooney | 36 pages | 01 Feb 1989 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780064430876 | English | New York, NY, United States Chanticleer and the Fox PDF Book Folk Tales. And t I find it interesting that so many of the comments on this book were about the vocabulary being too big azure, sow, debonair and the story being too long to hold the attention of small children. This would be particularly useful when students are illustrating their own stories. The Three Little Pigs. The Biggest Bear. Written by a librarything. It was anticlimactic and ended abruptly. Add to Cart. I was exposed to the best folk music that made me aware of the musical tradition of my country Ella Jenkins, John Langstaff, Tom Glazer, to name a few of my favs. It says on one of the cover flaps that the illustrator studied illuminated manuscripts and borrowed some chickens in order to make these pictures. I don't know what other books were competing for the Caldecot for , but this book is really charming. Feb 25, Chaitra rated it really liked it Shelves: picture-book , caldecott-medal. They make the words come alive and put the reader in the world of the widow and Chanticleer while still leaving room for the reader to use his own imagination. Open Preview See a Problem? All information is secure inside of Rainbow. Additional details. This one based on one of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales. Archived from the original on 9 January I remember loving this as a kid and I thoroughly enjoyed it upon my re-read. -

The Fables of La Fontaine [Book

ftnnk >E 3^ ^ By bequest of / C? ^ William Lukens Shoemaker PART VII. i ^ POETRY—Vol. I., Part 2 ' A D I CO ) A / 3j^ \ THE FABLES OF LA FONTAINE TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY E. WRIGHT. The Dairy Woman. LONDON i INGRAM, COOKE, AND CO. 227, STRAND. 1853. \\ ^S>\\> ^^v>V Gift. W. L. Shoemaker 7 S '06 \ THE FABLES ©F LA FONTAINE TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH, By ELIZUR WRIGHT, June. VOL. I. 119 INTKODTJCTION. This elegant translation of the most famous fabulist of modern times (if we may- be allowed to call tbe seventeenth century modern), is the work of an American author, who has admirably succeeded in embodying both the spirit, the grace, and the vivacity of the original in the translation. As Fables have interested and instructed mankind in every age, and as the Fables of La Fontaine may be said to be the standard collection of modern times, this translation has been considered as a most appropriate addition to the Universal Library. London, February, 1853.- 120 A PREFACE ON FABLE, THE FABULISTS, AND LA FONTAINE, BY THE TRANSLATOR. Human nature, when fresh from the hand of God, Himerians on their guard against the tyranny of was full of poetry. Its sociality could not be pent Phalaris by the fable of the Horse and the Stag. within the bounds of the actual. To the lower Cyrus, for the instruction of kings, told the story inhabitants of air, earth, and water,—and even to of the fisher obliged to use his nets to take the- those elements themselves, in all their parts and fish that turned a deaf ear to the sound of his flute.