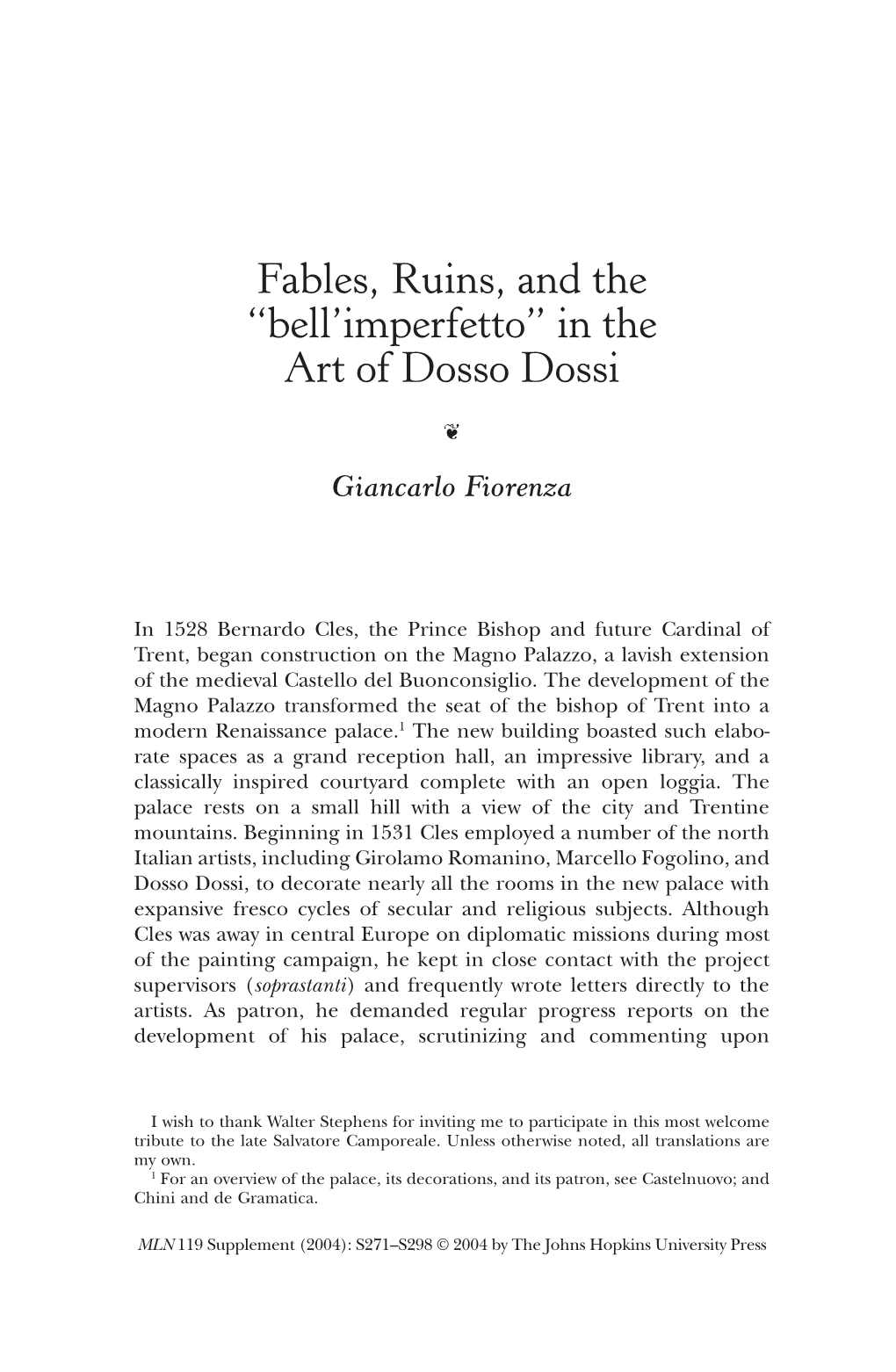

In the Art of Dosso Dossi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Life in Italian Painting

UC-NRLF III' m\ B 3 S7M 7bS THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTED BY PROF. CHARLES A. KOFOID AND MRS. PRUDENCE W. KOFOID ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING THt VISION OF ST EUSTACE Naiionai. GaM-KUV ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING BY WILLIAM NORTON HOWE, M.A. LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & COMPANY, LTD. 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE 1912 [All rights reserved] Printed by Ballantvne, Hanson 6* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh / VX-/ e3/^ H67 To ©. H. PREFACE I OWE to Mr. Bernhard Berenson the suggestion which led me to make the notes which are the foundation of this book. In the chapter on the Rudiments of Connoisseurship in the second series of his Study and Criticism of Italian Art, after speaking of the characteristic features in the painting of human beings by which authorship " may be determined, he says : We turn to the animals that the painters, of the Renaissance habitually intro- duced into pictures, the horse, the ox, the ass, and more rarely birds. They need not long detain us, because in questions of detail all that we have found to apply to the human figure can easily be made to apply by the reader to the various animals. I must, however, remind him that animals were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. Vasari, for instance, gets into a fury of contempt when describing Sodoma's devotion to pet birds and horses." Having from my schooldays been accustomed to keep animals and birds, to sketch them and to look vii ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING for them in painting, I had a general recollection which would not quite square with the statement that they were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. -

017 Harvard Classics

THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books soldier could see through the window how the peopL were hurrying out of the town to see him hanged —P«ge 354 THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Folk-Lore and Fable iEsop • Grimm Andersen With Introductions and No/« Volume 17 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 BY P. F. COLLIER & SON MANUFACTURED IN U. *. A. CONTENTS ^SOP'S FABLES— PAGE THE COCK AND THE PEARL n THE WOLF AND THE LAMB n THE DOG AND THE SHADOW 12 THE LION'S SHARE 12 THE WOLF AND THE CRANE 12 THE MAN AND THE SERPENT 13 THE TOWN MOUSE AND THE COUNTRY MOUSE 13 THE FOX AND THE CROW 14 THE SICK LION 14 THE ASS AND THE LAPDOG 15 THE LION AND THE MOUSE 15 THE SWALLOW AND THE OTHER BIRDS 16 THE FROGS DESIRING A KING 16 THE MOUNTAINS IN LABOUR 17 THE HARES AND THE FROGS 17 THE WOLF AND THE KID 18 THE WOODMAN AND THE SERPENT 18 THE BALD MAN AND THE FLY 18 THE FOX AND THE STORK 19 THE FOX AND THE MASK 19 THE JAY AND THE PEACOCK 19 THE FROG AND THE OX 20 ANDROCLES 20 THE BAT, THE BIRDS, AND THE BEASTS 21 THE HART AND THE HUNTER 21 THE SERPENT AND THE FILE 22 THE MAN AND THE WOOD 22 THE DOG AND THE WOLF 22 THE BELLY AND THE MEMBERS 23 THE HART IN THE OX-STALL 23 THE FOX AND THE GRAPES 24 THE HORSE, HUNTER, AND STAG 24 THE PEACOCK AND JUNO 24 THE FOX AND THE LION 25 1 2 CONTENTS PAGE THE LION AND THE STATUE 25 THE ANT AND THE GRASSHOPPER 25 THE TREE AND THE REED 26 THE FOX AND THE CAT 26 THE WOLF IN SHEEP'S CLOTHING 27 THE DOG IN THE MANGER 27 THE MAN AND THE WOODEN GOD 27 THE FISHER 27 THE SHEPHERD'S -

Aesop's Fables

1-21 22-42 The Cock and the Pearl The Frog and the Ox The Wolf and the Lamb Androcles The Dog and the Shadow The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts The Lion's Share The Hart and the Hunter The Wolf and the Crane The Serpent and the File The Man and the Serpent The Man and the Wood The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse The Dog and the Wolf The Fox and the Crow The Belly and the Members The Sick Lion The Hart in the Ox-Stall The Ass and the Lapdog The Fox and the Grapes The Lion and the Mouse The Horse, Hunter, and Stag The Swallow and the Other Birds The Peacock and Juno The Frogs Desiring a King The Fox and the Lion The Mountains in Labour The Lion and the Statue The Hares and the Frogs The Ant and the Grasshopper The Wolf and the Kid The Tree and the Reed The Woodman and the Serpent The Fox and the Cat The Bald Man and the Fly The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing The Fox and the Stork The Dog in the Manger The Fox and the Mask The Man and the Wooden God The Jay and the Peacock The Fisher 43-62 63-82 The Shepherd's Boy The Miser and His Gold The Young Thief and His Mother The Fox and the Mosquitoes The Man and His Two Wives The Fox Without a Tail The Nurse and the Wolf The One-Eyed Doe The Tortoise and the Birds Belling the Cat The Two Crabs The Hare and the Tortoise The Ass in the Lion's Skin The Old Man and Death The Two Fellows and the Bear The Hare With Many Friends The Two Pots The Lion in Love The Four Oxen and the Lion The Bundle of Sticks The Fisher and the Little Fish The Lion, the Fox, and the Beasts Avaricious and Envious The Ass's Brains -

Krilòff's Fables;

5 5 (7 V 3 ^ '^\^^ aofcaiifo% 5> . V f ^^Aavaanii^ ^^Aavnaiiiv^ ^MEUNIVERS/A >:101% ^^•UBRARY6>/r, : be- _ ^ '^.i/OJnVDJO'^ ^^WEUNIVERS/^ ^lOSANCElfj> zmoR^y <ril30HVS01^ %a3AINnJl\V "^OWSiUW^ ^AOJITVDJO^ ^AOJITVD-JO^ ^^ ^OFCAIIFO/?^ AWEUNIVERva CO -< ^c'AHvaan^' %133NVS01^^ AWEUNIVERSy^ ANGELA* /:^ =6 <=- vN- , \ME UNIVERJ/A v>;lOSANCElfj>. ^OFCAll FO/?^ ^OFCAIIFOI?^ ^OFCAIIFO;?^ -I^EUNIVERSyA .v pa ^J'JiaQKvso^^^ AWEl)NIVERy/A v>:lOSANCEl£r;x §1 ir-U b. s -< J' JNVSOl^ aWEUNIVERSZ/v ^lOSANCElfx^ ^OFCAllFOff^ WcOfC <rinONVS01^ %a3AINft3W^ -^^^•UBRARYO^ 5i\EUNIVER% ^^HOiim JO 4^OFCAllF0ff^ ^OFCAIIFO;?^ 5MEUNIVERS/// va'diii^^^' ^<?AavHani jjimm'^ .\WEUNIVER% ^^10SANCEI%^ 4,>MUBRARYQ^^ >i V ^ <5 , ,\WEUNIVERS-//, vvlOSANCElfj-;> ^OFCALIf : KRILOFF'S FABLES Translated from the Russian into English in the original metres BY FILLINGHAM COXWELL, m.d. Author of Chronicles of Man, Through Russia in War Time WITH 4 PIRATES LONDON KEGAN PAUL. TRENCH, TRUBNER & Co., Ltd. NEW YORK : E. P. BUTTON & Co. A Printed Great Britain by BovvERiNG & Co., St. Andrev.'s Printing Works, George Street, Plymouth. PREFACE RILOFF is such a remarkable figure in Russian literature, and his Fables are so interesting and admirable that I have ventured to render eighty-six of them into English. No prose translation can do this poet-fabulist justice, but a rendering in metrical fonns, corresponding with his own, may give readers some idea of his merits. If it be recalled that the source of most fables is hidden in the mists of antiquity, then Kriloff 's originality can scarcely fail to be a recommendation. He wrote, in all, 201 fables and there seems little doubt that, in four-fifths of them, he was not indebted to anyone. -

Aesop's Fables, However, Includes a Microsoft Word Template File for New Question Pages and for Glos- Sary Pages

1 æsop’s fables Click here to jump to the Table of Contents 2 Copyright 1993 by Adobe Press, Adobe Systems Incorporated. All rights reserved. The text of Aesop’s Fables is public domain. Other text sections of this book are copyrighted. Any reproduction of this electronic work beyond a personal use level, or the display of this work for public or profit consumption or view- ing, requires prior permission from the publisher. This work is furnished for informational use only and should not be construed as a commitment of any kind by Adobe Systems Incorporated. The moral or ethical opinions of this work do not necessarily reflect those of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Adobe Systems Incorporated assumes no responsibilities for any errors or inaccuracies that may appear in this work. The software and typefaces mentioned on this page are furnished under license and may only be used in accordance with the terms of such license. This work was electronically mastered using Adobe Acrobat software. The original composition of this work was created using FrameMaker. Illustrations were manipulated using Adobe Photoshop. The display text is Herculanum. Adobe, the Adobe Press logo, Adobe Acrobat, and Adobe Photoshop are trade- marks of Adobe Systems Incorporated which may be registered in certain juris- dictions. 3 Contents • Copyright • How to use this book • Introduction • List of fables by title • Aesop’s Fables • Index of titles • Index of morals • How to create your own glossary and question pages • How to print and make your own book • Fable questions Click any line to jump to that section 4 How to use this book This book contains several sections. -

Aesop's Fables

AESOP’S FABLES BY AESOP © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc. © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc © 2008 Tantor Media, Inc This PDF eBook was produced in the year 2008 by Tantor Media, Incorporated, which holds the copyright thereto. -

Aesop's and Other Fables

Aesop’s and other Fables Æsop’ s and other Fables AN ANTHOLOGY INTRODUCTION BY ERNEST RHYS POSTSCRIPT BY ROGER LANCELYN GREEN Dent London Melbourne Toronto EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY Dutton New York © Postscript, J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd, 1971 AU rights reserved Printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, Guildford, Surrey for J. M. DENT & SONS LTD Aldine House, 33 Welbeck Street, London This edition was first published in Every matt’s Library in 19 13 Last reprinted 1980 Published in the USA by arrangement with J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd No 657 Hardback isbn o 460 00657 6 No 1657 Paperback isbn o 460 01657 1 CONTENTS PAGE A vision o f Æ sop Robert Henryson , . * I L FABLES FROM CAXTON’S ÆSOP The Fox and the Grapes. • • 5 The Rat and the Frog 0 0 5 The W olf and the Skull . • 0 0 5 The Lion and the Cow, the Goat and the Sheep • 0 0 6 The Pilgrim and the Sword • • 0 6 The Oak and the Reed . 0 6 The Fox and the Cock . , . 0 7 The Fisher ..... 0 7 The He-Goat and the W olf . • •• 0 8 The Bald Man and the Fly . • 0 0 8 The Fox and the Thom Bush .... • t • 9 II. FABLES FROM JAMES’S ÆSOP The Bowman and the Lion . 0 0 9 The W olf and the Crane . , 0 0 IO The Boy and the Scorpion . 0 0 IO The Fox and the Goat . • 0 0 IO The Widow and the Hen . 0 0 0 0 II The Vain Jackdaw ... -

Dosso Dossi, the Painter

Oltrepò Mantovano Itineraries Dosso Dossi, the painter Giovanni di Niccolò Luteri, commonly known as Dosso Dossi (San Giovanni del Dosso, 1474 - Ferrara, 1542), was an Italian painter. He was the main artist in the Este Castle in Ferrara in the early sixteenth century, the era of Ariosto, whose fantastic stories was a striking interpreter. His works are exhibited in the most prestigious museums around the world. Biographical data on the artist is poor. We know where he was born, but not when. His father was from Trentino and was treasurer of the court of Ferrara. In 1485 it is documented that the family lived in Dosso della Scaffa (today San Giovanni del Dosso). As the father became the owner of the small farm in Dosso della Scaffa, he passed down his children the name of the patron saint of the village: John and Baptist. Dosso Dossi in San Giovanni del Dosso. In his education, Dosso did not directly draw from the prestigious Ferrara school of the fifteenth century, but was influenced by it only after having learned the secrets of Venetian painters, especially Giorgione. At these basic teachings, he then added references to classical culture and to Raffaello, as well as his own well-developed narrative attitude. In 1510 he was in Mantua at the service of the Gonzaga, and in 1514 he was appointed court painter in Ferrara. In this role, he was involved in the main decorative challenges of Alfonso d'Este, such as Alabaster Camerini. With frequent travels (to Florence, Rome and especially Venice), Dosso always stayed abreast to what was new in art in the neuralgic artistic centers of the peninsula, starting a profitable dialogue with Tiziano, from whom he recalled the richness of color and the wide openings of landscapes. -

Aesop's Fables

451-CE2565 ☆ (CANADA $ 5.99) ☆ U.S. $4.95 AESOP’S FABLES Including: The Fox and the Grapes The Ants and the Grasshopper The Country Mouse and the City Mouse ...and 200 other famous fables SELECTED AND ADAPTED BY JACK ZIPES AESOP'S FABLES Selected and Adapted by Jack Zipes A SIGNET CLASSIC SIGNET CLASSIC Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York. New York 10014, U.S.A. Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England Penguin Books Australia Ltd. Ringwood. Victoria, Australia Penguin Books Canada Ltd. 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario. Canada M4V 3B2 Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand Penguin Books Ltd. Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex. England Published by Signet Classic, an imprint of New American Library, a division of Penguin Books USA Inc. First Signet Classic Printing, October. 1992 10 987654321 Copyright © Jack Zipes. 1992 All rights reserved REGISTERED TRADEMARK—MARCA REGISTRADA Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 92-60921 Printed in the United States of America BOOKS ARE AVAILABLE AT QUANTITY DISCOUNTS WHEN USED TO PROMOTE PRODUCTS OR SERVICES. FOR INFORMATION PLEASE WRITE TO PREMIUM MAR KETING DIVISION. PENGUIN BOOKS USA INC.. 375 HUDSON STREET. NEW YORK. NEW YORK 10014. If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Contents -

Raffigurante L'arcangelo Michele Tra I Ss. Valeriano E Giovanni Battista, La

SACCHIS, Giovanni Antonio de’, detto il Pordenone SACCHIS (de Corticellis, Regillo), Giovanni Antonio de’, detto il Pordenone – Nacque verosimilmente a Pordenone verso il 1483-84, figlio del mastro murario Angelo da Brescia (o da Corticelle, donde il de Corticellis che lo designa in alcuni documenti). Nel primo documento noto, del 19-21 maggio 1504, Giovanni Antonio è già indicato come pittore e risulta associato a un collega di origine tedesca, Bartolomeo da Colonia: fatto non strano in una città imperiale quale Pordenone. La cultura figurativa settentrionale è del resto assai ben attestata nel Friuli di primo Rinascimento. A conferma della propria emancipazione, il successivo 16 ottobre il Pordenone sottoscrisse i patti dotali con Anastasia, figlia del maestro Stefano di Giamosa. La prima opera pittorica di cui possediamo la data è il trittico ad affresco della parrocchiale di Valeriano, raffigurante l’Arcangelo Michele tra i ss. Valeriano e Giovanni Battista, la cui iscrizione (oggi pressoché illeggibile ma riportata da Venturi, 1908, pp. 457 s.) suona: «Miser Durigo de / Lasin a fato far questo / S. Michiel per sua devotione / MDCCC: VI. Adì 6 / Zuane Antonio de Sacchis / abitante in Spilimbergo». Il 15 gennaio 1507 il Pordenone fu testimone, in Cordovado, alla consegna della dote al pittore spilimberghese Michele Stella (Pecoraro, 2007, pp. 104, 168 s.). L’informazione della residenza di Giovanni Antonio a Spilimbergo è confermata da un documento del 19 ottobre 1507 che elenca il pittore tra i periti incaricati del collaudo di una perduta pala di Gianfrancesco da Tolmezzo per Castel d’Aviano (Goi, 1991, p. 45, e le precisazioni di Furlan - Francescutti, 2015, p. -

I Tre Crocifissi

SIRBeC scheda OARL - C0050-00030 I Tre Crocifissi Foppa Vincenzo Link risorsa: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/opere-arte/schede/C0050-00030/ Scheda SIRBeC: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/opere-arte/schede-complete/C0050-00030/ SIRBeC scheda OARL - C0050-00030 CODICI Unità operativa: C0050 Numero scheda: 30 Codice scheda: C0050-00030 Visibilità scheda: 3 Utilizzo scheda per diffusione: 03 Tipo scheda: OA Livello ricerca: P CODICE UNIVOCO Codice regione: 03 Numero catalogo generale: 00643327 Ente schedatore: R03/ Accademia Carrara Ente competente: S27 RELAZIONI RELAZIONI CON ALTRI BENI Tipo relazione: è compreso Tipo scheda: COL Codice bene: 03 Codice IDK della scheda correlata: COL-LMD30-0000012 OGGETTO Gruppo oggetti: pittura OGGETTO Definizione: dipinto Disponibiltà del bene: reale SOGGETTO Categoria generale: sacro Identificazione: Cristo crocifisso tra i due ladroni Titolo: I Tre Crocifissi Pagina 2/44 SIRBeC scheda OARL - C0050-00030 LOCALIZZAZIONE GEOGRAFICO-AMMINISTRATIVA LOCALIZZAZIONE GEOGRAFICO-AMMINISTRATIVA ATTUALE Stato: Italia Regione: Lombardia Provincia: BG Nome provincia: Bergamo Codice ISTAT comune: 016024 Comune: Bergamo COLLOCAZIONE SPECIFICA Tipologia: museo Denominazione: Accademia Carrara Denominazione spazio viabilistico: Piazza Giacomo Carrara Denominazione struttura conservativa - livello 1: Accademia Carrara Tipologia struttura conservativa: museo Collocazione originaria: NO ACCESSIBILITA' DEL BENE Accessibilità: SI ALTRE LOCALIZZAZIONI GEOGRAFICO-AMMINISTRATIVE Tipo di localizzazione: luogo di provenienza -

L'arte Del Quattrocento E Del Cinquecento

FIORELLA FRISONI L’arte del Quattrocento e del Cinquecento Render conto della bibliografia storico artistica sull’arte del Quattro- cento e del Cinquecento, e in particolare sulla pittura, nei quarant’anni successivi alla pubblicazione della Storia di Brescia, che resta pur sempre tappa fondamentale per gli studi, è impresa tale da far tremare le vene ai polsi e resta davvero difficile darne conto in maniera esaustiva. Nella monumentale impresa voluta da Giovanni Treccani degli Alfieri si susse- guivano nel secondo tomo del libro, con un’appendice nel terzo, ad opera di Pier Virgilio Begni Redona, su La pittura manierista, dopo i contributi di Adriano Peroni sull’architettura e la scultura nei secoli XV e XVI, quelli di Gaetano Panazza sulla pittura del Quattrocento, prima e seconda metà, intervallati dal capitolo su Foppa che Edoardo Arslan aveva voluto per sé, e quello di Renata Bossaglia sulla pittura del Cinquecento attraverso i “maggiori” (vale a dire Romanino, Moretto e Savoldo) e i loro seguaci1. Il largo spazio dedicato nell’opera ai problemi storico-artistici è se- gno dell’interesse della città e delle sue istituzioni, ma anche del mondo scientifico, per quei problemi, interesse che sfocerà negli anni successivi in lodevoli e apprezzate iniziative, per cui il bilancio degli studi nei qua- rant’anni successivi alla pubblicazione può considerarsi assolutamente positivo. Meritano una prima segnalazione le mostre organizzate, dopo le date di uscita dei corposi volumi, dai Civici Musei di arte e storia di Brescia e dedicate alle figure principali dell’arte bresciana: la prima, del 1965, dedicata a Gerolamo Romanino2; le successive dedicate rispetti- vamente al Moretto, nel 19883; a Giovan Girolamo Savoldo, nel 19904; 1 Storia di Brescia, II, La dominazione veneta (1426-1575), Brescia 1963: Adriano Peroni, L’architettura e la scultura nei secoli XV e XVI, pp.