Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles the Kingdom of Tonga

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles The Kingdom of Tonga Part I Overview and main indicators 1. Country brief 2. General geographic and economic indicators 3. FAO Fisheries statistics Part II Narrative (2014) 4. Production sector Marine sub-sector Inland sub-sector Aquaculture sub-sector - NASO Recreational sub-sector Source of information United Nations Geospatial Information Section http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm 5. Post-harvest sector Imagery for continents and oceans reproduced from GEBCO, www.gebco.net Fish utilization Fish markets 6. Socio-economic contribution of the fishery sector Role of fisheries in the national economy Trade Food security Employment Rural development 7. Trends, issues and development Constraints and opportunities Government and non-government sector policies and development strategies Research, education and training Foreign aid 8. Institutional framework 9. Legal framework 10. Annexes 11. References Additional information 12. FAO Thematic data bases 13. Publications 14. Meetings & News archive FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Part I Overview and main indicators Part I of the Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profile is compiled using the most up-to-date information available from the FAO Country briefs and Statistics programmes at the time of publication. The Country Brief and the FAO Fisheries Statistics provided in Part I may, however, have been prepared at different times, which would explain any inconsistencies. Country brief Current situation Tonga is an archipelagic nation of some 150 islands (36 of which are inhabited), representing a total land area of about 747 km2. -

Fisheries and Wildlife Research 1982

Fisheries and Wildlife Research 1982 Activities in the Divisions of Research for the Fiscal Year 1982 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Fisheries Thomas G. Scott, Wildlife Published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Printed by the U.S. Government Printing Office Denver, Colorado • 1983 •• , :e. ' • Noel Snyder, field biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Condor Research Center, carries a travel case containing a California condor chick from the chick's nesting site northeast of Los Angeles. The bird was captured in August, after biologists determined that the parents were not feeding the chick regularly. The chick was taken to the San Diego Wild Animal Park to begin a captive breeding program for this critically endangered species. Dr. Phil Ensley, veterinarian for the Zoological Society of San Diego, accompanied Dr. Snyder on the capture operation. Photo by H. K. Snyder. 11 Contents Foreword ...................................................... iv Tunison Laboratory of Fish Nutrition ........ 86 Fisheries and Wildlife Research .............. 1 National Reservoir Research Program . 88 Animal Damage Control ............................ 2 East Central Reservoir Investigations . 89 Denver Wildlife Research Center ............ 2 Multi-Outlet Reservoir Studies .................. 91 Southeast Reservoir Investigations .......... 93 Environmental Contaminant Evaluation 25 White River Reservoir Studies .................... 95 Columbia National Fisheries Research Seattle National Fishery Research Laboratory .............................................. -

Introducing the Face of Fitzroy G

ANNUAL REPORT NIWA 2013/14 Q Enhancing the benefits of New Zealand’s natural resources Cover Q. How is NIWA translating forecast data generated by its supercomputer FitzRoy into meaningful and relevant weather information for New Zealanders? A. In early 2014, meteorologist and weather communicator Chris Brandolino joined NIWA’s weather and climate team. Chris has wide international experience explaining the weather using a style and language that engages and makes sense to his audience. NIWA’s goal is to greatly improve the relevance of weather information communicated to the New Zealand public, shifting the focus from forecasting weather alone (“expect rain this afternoon”) to forecasting the impacts of weather on lives and livelihoods (“get the washing dry, or fertilise your pasture, this morning”). NIWA has also increased its capacity in other areas of weather communication – including graphics production – to help translate FitzRoy’s sophisticated technical outputs into meaningful public information. Inside Cover Q. How is NIWA helping farmers improve productivity and reduce risk? A. At the 2014 National Fieldays at Mystery Creek, NIWA launched NIWAFarmMet, a new subscription-based, online weather forecasting and information service tailored to New Zealand farmers (read more on page 33 and visit farmmet.niwa.co.nz). NIWAFarmMet is designed to help farmers identify opportunities to carry out key weather-dependent activities like fertilising, irrigating and harvesting, and prepare for potentially damaging weather like high winds, frosts and floods. Its forecasts are highly localised, rather than tailored to an entire region or the nearest big town, and presented in easy-to-interpret graphical form. NIWA staff demonstrated the product to hundreds of farmers at Fieldays, along with other aspects of its growing suite of weather and climate services. -

Lessons from Past and Current Aquaculture Inititives in Selected

SUB-REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE PACIFIC ISLANDS TCP/RAS/3301 LESSONS FROM PAST AND CURRENT AQUACULTURE INITIATIVES IN SELECTED PACIFIC ISLAND COUNTRIES Prepared by Pedro B. Bueno FAO Consultant ii Lessons learned from Pacific Islands Countries The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. © FAO, 2014 FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www. fao.org/contact-us/licence-request or addressed to [email protected]. -

World Bank Documents As Required, Such As an ESMP

Public Disclosure Authorized Halafononga Ki Ha Ngatai Tu’uloa Tonga: Pathway to Sustainable Oceans (TongaFish Pathway) Project World Bank: P164941 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Public Disclosure Authorized VERSION: Final, March 2019 Tonga: Pathway to Sustainable Oceans (P164941) – Environmental and Social Management Framework |March 2019 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 6 2 Purpose and Scope of the ESMF ........................................................................................................... 7 3 Description of the Project Components and Typology of Sub-Projects ............................................... 8 3.1 Project Subcomponents ................................................................................................................ 8 3.2 Types of Subproject Activities ..................................................................................................... 11 4 Environmental and Social Context ...................................................................................................... 12 4.1 Economy ...................................................................................................................................... 12 4.2 Coastal and Marine Ecosystems ................................................................................................. 12 4.3 -

THE STATE of WORLD FISHERIES and AQUACULTURE 2002 Editing, Design, Graphics and Desktop Publishing: Editorial Group FAO Information Division

THE STATE OF WORLD FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE 2002 Editing, design, graphics and desktop publishing: Editorial Group FAO Information Division The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ISBN 92-5-104842-8 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Publishing Management Service, Information Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by e-mail to [email protected] © FAO 2002 ISSN 1020-5489 THE STATE OF WORLD FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE 2002 FAO Fisheries Department FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2002 Y !""#Z %&'&(% )* &Z+!""#/3 6"X/3"<)( = /3& Z +>&Z>!""!/ >>X/>>< ?G "H6>H( G(J'!""!? G?K &"?3 ?>=& & ? ? 3>/GX>< &G? #>!""!( (?! H G &?Q ?W ? > ? HX & = X = %3# !"!#$%!! & & ( ' (& 3 () 3 *( G *+ 6 *- &. .' %3! / "$13"""41 '' 3 '' '' % '+ '5 $6$$6444741 '- 3 '- +* X +& 4!! +' 3 +' ++ % +) +5 873$$7$$9$41 +- 3 +- ): % )* & )& 6!;$"! ). 3 ). )' % )+ X 5* %3Q //8 !$19$76$3 5) J& 5) H 5) ( 55 -: -: 4"$!4 46!"7!!4 -( J& -( X -* > -& 9"44"4 -' -' (H -' % -) ;$!7$"$4"6$"$ -- -- ) (:: (:* 3 (:' ( (:+ %3W < ! ((( !$19"=44"!!" ((( (G ((* ( ((. -

Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan: 2010-2014 / Produced by the Ministry of Fisheries with the Assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community

Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan © SPC, 2010 – Cover design: Muriel Borderie – SPC Publications Section Muriel design: – SPC Publications Borderie © SPC, 2010 – Cover 2010-2014 Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan 2010-2014 Produced by the Ministry of Fisheries with the assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community Secretariat of the Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia, 2010 © Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2010 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Tonga aquaculture commodity development plan: 2010-2014 / produced by the Ministry of Fisheries with the assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community 1. Aquaculture – Tonga – History 2. Aquaculture – Law and legislation – Tonga 3. Aquaculture – Management – Tonga I. Title. II. Tonga. Ministry of Fisheries. III. Secretariat of the Pacific Community. 639.809 961 2 AACR2 ISBN: 978-982-00-0423-8 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BP D5 98848 Noumea Cedex New Caledonia -

South Pacific Islands Fisheries Development Agency, Australia

FI:DP/RAS/69/102 Terminal Report SOUTH PACIFIC ISLANDS FISilERlES DEVELOPMENT AGENCY AUS'l'RALIA, FRANCE, NEW ZEALAND, UNI'rED KINGDOM, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, WES'l'ERN SAMOA PROJECT FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDA'I'IONS Report prepared for the participating Governments by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations acting as executing agency for the United Nations Development ProgTamme UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD .AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION Qli' THE UNITED NATIONS Rome 7 1975 Some of the territories covered by the activities of the Projeot attained independenoe after the Plan of Operation was signed but, in accordance with FAQ practice, this Report is addressed to the signatories of the Plan. iii TABLE OF CON'l1ENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 .1 ProJect l)ackground and objectives 1 1 .2 Project implementation 2 1 .2 .1 General administration 2 1.2.2 Problems enoour1t0red 2 1.2.3 Review mission 5 Jt.'valuation of aotivi ties 5 2. PROJEG'l' RESUL'l'S AND CONCLUSIOUS 6 Coastal fioheries 6 2 .1. ·1 Out-·of-r0ef fishing 6 2 .1 .2 Reef and lagoon resources 6 2 .1.3 Bcche-de-mer resources 7 2.1.4 Turtle resources 7 2.1.5 Mangrove fishery 8 J\quacul ture 8 illvaluation of potential 8 Demonstrations and feasibility studies 9 2.3 Boat·bui lding 11 2.3.1 General activities 11 2.).2 lt,iji 12 2.3.3 American Samoa 12 2.3.4 Western Samoa 12 2.).5 Tonga 12 2.).6 J\ctivitieo of interest to more than one territory Publications RECOMMENDATIONS 1tj. -

Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan

Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan © SPC, 2010 – Cover design: Muriel Borderie – SPC Publications Section Muriel design: – SPC Publications Borderie © SPC, 2010 – Cover 2010-2014 Tonga Aquaculture Commodity Development Plan 2010-2014 Produced by the Ministry of Fisheries with the assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community Secretariat of the Pacific Community Noumea, New Caledonia, 2010 © Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2010 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided that SPC and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published without permission. Original text: English Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Tonga aquaculture commodity development plan: 2010-2014 / produced by the Ministry of Fisheries with the assistance of the Secretariat of the Pacific Community 1. Aquaculture – Tonga – History 2. Aquaculture – Law and legislation – Tonga 3. Aquaculture – Management – Tonga I. Title. II. Tonga. Ministry of Fisheries. III. Secretariat of the Pacific Community. 639.809 961 2 AACR2 ISBN: 978-982-00-0423-8 Secretariat of the Pacific Community BP D5 98848 Noumea Cedex New Caledonia -

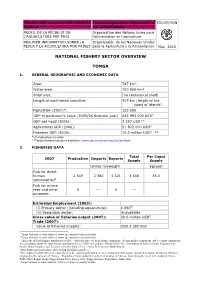

National Fishery Sector Overview Tonga

FISHERY AND AQUACULTURE COUNTRY Food and Agriculture Organization of FID/CP/TON PROFILE the United Nations PROFIL DE LA PÊCHE ET DE Organisation des Nations Unies pour L‟AQUACULTURE PAR PAYS l'alimentation et l'agriculture RESUMEN INFORMATIVO SOBRE LA Organización de las Naciones Unidas PESCA Y LA ACUICULTURA POR PAÍSES para la Agricultura y la Alimentación May 2010 NATIONAL FISHERY SECTOR OVERVIEW TONGA 1. GENERAL GEOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC DATA Area: 747 km² Water area: 700 000 km² Shelf area: [no continental shelf] Length of continental coastline: 419 km (length of the coast of islands) Population (2007)*: 103 000 GDP at purchaser's value (2005/06 financial year) 243 993 000 USD1 GDP per head (2006): 2 397 USD** Agricultural GDP (2006): 51 872 000 USD2 Fisheries GDP (2006): 10.0 million USD3 ** *UN Population Division **Tonga National account statistics: www.spc.int/prism/country/to/stats 2. FISHERIES DATA Total Per Caput 2007 Production Imports Exports Supply Supply tonnes liveweight kg/year Fish for direct human 2 549 2 380 1 321 3 608 35.0 consumption4 Fish for animal feed and other 0 --- 0 --- purposes Estimated Employment (2003): (i) Primary sector (including aquaculture): 1 0505` (ii) Secondary sector: Unavailable Gross value of fisheries output (2007): 20.6 million USD6 Trade (2007): Value of fisheries imports: USD 2 390 000 1 Tonga National account statistics: www.spc.int/prism/country/to/stats 2 Tonga National account statistics: www.spc.int/prism/country/to/stats 3 This is the official fishing contribution to GDP – which includes (a) local market component, (b) non-market component, and (c) export component; A recalculation shows the total fishing contribution to be USDD 12.0 million: Gillett (2009). -

Tonga Fisheries Bibliography

Tonga Fisheries Bibliography Robert Gillett January 1994 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Technical Cooperation Programme TCP/TON/2251 Table of Contents Page Introduction ............................................................................................................. iii Location of References ......................................................................................... v References Listed by Author ................................................................................ 1 References Listed by Subject............................................................................... 38 Annual Reports .............................................................................................. 38 Aquaculture.................................................................................................... 39 Baitfish........................................................................................................... 41 Beche-de-Mer ................................................................................................ 42 Boats and Boatbuilding.................................................................................. 42 Bottomfish...................................................................................................... 45 Charts, Mapping, and Sailing Directions ....................................................... 47 Fish Aggregating Devices.............................................................................. 48 Fish Poisoning .............................................................................................. -

Review of Oceanian Species/Country Combinations Subject to Long-Standing Import Suspensions

Review of Oceanian species/country combinations subject to long-standing import suspensions (Version edited for public release) Prepared for the European Commission Directorate General Environment ENV.E.2. – Environmental Agreements and Trade by the United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre May, 2011 UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre PREPARED FOR 219 Huntingdon Road Cambridge The European Commission, Brussels, Belgium CB3 0DL United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0) 1223 277314 DISCLAIMER Fax: +44 (0) 1223 277136 The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect Email: [email protected] the views or policies of UNEP or contributory Website: www.unep-wcmc.org organisations. The designations employed and the ABOUT UNEP-WORLD CONSERVATION presentations do not imply the expressions of any MONITORING CENTRE opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP, the European Commission or contributory The UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre organisations concerning the legal status of any (UNEP-WCMC), based in Cambridge, UK, is the country, territory, city or area or its authority, or specialist biodiversity information and assessment concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or centre of the United Nations Environment boundaries. Programme (UNEP), run cooperatively with WCMC, a UK charity. The Centre's mission is to evaluate and highlight the many values of © Copyright: 2011, European Commission biodiversity and put authoritative biodiversity knowledge at the centre of decision-making. Through the analysis and synthesis of global biodiversity knowledge the Centre provides authoritative, strategic and timely information for conventions, countries and organisations to use in the development and implementation of their policies and decisions. The UNEP-WCMC provides objective and scientifically rigorous procedures and services.