Lessons from Past and Current Aquaculture Inititives in Selected

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishers and Fish Traders of Lake Victoria: Colonial

FISHERS AND FISH TRADERS OF LAKE VICTORIA: COLONIAL POLICY AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF FISH PRODUCTION IN KENYA, 1880-1978. by PAUL ABIERO OPONDO Student No. 34872086 submitted in accordance with the requirement for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject HISTORY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: DR. MUCHAPARARA MUSEMWA, University of the Witwatersrand CO-PROMOTER: PROF. LANCE SITTERT, University of Cape Town 10 February 2011 DECLARATION I declare that ‘Fishers and Fish Traders of Lake Victoria: Colonial Policy and the Development of Fish Production in Kenya, 1895-1978 ’ is my original unaided work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. I further declare that the thesis has never been submitted before for examination for any degree in any other university. Paul Abiero Opondo __________________ _ . 2 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to several fishers and fish traders who continue to wallow in poverty and hopelessness despite their daily fishing voyages, whose sweat and profits end up in the pockets of big fish dealers and agents from Nairobi. It is equally dedicated to my late father, Michael, and mother, Consolata, who guided me with their wisdom early enough. In addition I dedicate it to my loving wife, Millicent who withstood the loneliness caused by my occasional absence from home, and to our children, Nancy, Michael, Bivinz and Barrack for whom all this is done. 3 ABSTRACT The developemnt of fisheries in Lake Victoria is faced with a myriad challenges including overfishing, environmental destruction, disappearance of certain indigenous species and pollution. -

Download Book (PDF)

M o Manual on IDENTIFICATION OF SCHEDULE MOLLUSCS From India RAMAKRISHN~~ AND A. DEY Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkota 700 053 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA KOLKATA CITATION Ramakrishna and Dey, A. 2003. Manual on the Identification of Schedule Molluscs from India: 1-40. (Published : Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published: February, 2003 ISBN: 81-85874-97-2 © Government of India, 2003 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any from or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • -This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, resold hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE India : Rs. 250.00 Foreign : $ (U.S.) 15, £ 10 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, 234/4, AJ.C. Bose Road, 2nd MSO Building (13th Floor), Nizam Palace, Kolkata -700020 and printed at Shiva Offset, Dehra Dun. Manual on IDENTIFICATION OF SCHEDULE MOLLUSCS From India 2003 1-40 CONTENTS INTRODUcrION .............................................................................................................................. 1 DEFINITION ............................................................................................................................ 2 DIVERSITY ................................................................................................................................ 2 HA.B I,.-s .. .. .. 3 VAWE ............................................................................................................................................ -

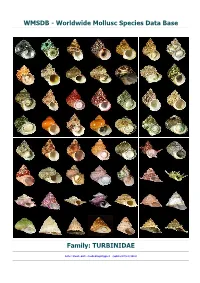

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Food Microbiology Unveiling Hákarl: a Study of the Microbiota of The

Food Microbiology 82 (2019) 560–572 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Microbiology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/fm Unveiling hákarl: A study of the microbiota of the traditional Icelandic T fermented fish ∗∗ Andrea Osimania, Ilario Ferrocinob, Monica Agnoluccic,d, , Luca Cocolinb, ∗ Manuela Giovannettic,d, Caterina Cristanie, Michela Pallac, Vesna Milanovića, , Andrea Roncolinia, Riccardo Sabbatinia, Cristiana Garofaloa, Francesca Clementia, Federica Cardinalia, Annalisa Petruzzellif, Claudia Gabuccif, Franco Tonuccif, Lucia Aquilantia a Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie, Alimentari ed Ambientali, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Via Brecce Bianche, Ancona, 60131, Italy b Department of Agricultural, Forest, and Food Science, University of Turin, Largo Paolo Braccini 2, Grugliasco, 10095, Torino, Italy c Department of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Pisa, Via del Borghetto 80, Pisa, 56124, Italy d Interdepartmental Research Centre “Nutraceuticals and Food for Health” University of Pisa, Italy e “E. Avanzi” Research Center, University of Pisa, Via Vecchia di Marina 6, Pisa, 56122, Italy f Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Umbria e delle Marche, Centro di Riferimento Regionale Autocontrollo, Via Canonici 140, Villa Fastiggi, Pesaro, 61100,Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Hákarl is produced by curing of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) flesh, which before fermentation Tissierella is toxic due to the high content of trimethylamine (TMA) or trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Despite its long Pseudomonas history of consumption, little knowledge is available on the microbial consortia involved in the fermentation of Debaryomyces this fish. In the present study, a polyphasic approach based on both culturing and DNA-based techniqueswas 16S amplicon-based sequencing adopted to gain insight into the microbial species present in ready-to-eat hákarl. -

Studies of Age and Growth of the Gastropod Turbo Marmoratus Determined from Daily Ring Density B

i I Proc 8th Int Coral Reef Sym 2:1351-1356. 1997 STUDIES OF AGE AND GROWTH OF THE GASTROPOD TURBO MARMORATUS DETERMINED FROM DAILY RING DENSITY B. Bourgeois1, C.E. Payril and P. Bach2 1 Laboratoire d'Ecologie Marine, Universite Française du Pacifique, BP 6570 FaaalAéroport, Tahiti, French Polynesia * ORSTOM, BP 529, Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia . ABSTRACT This is a study of the age and growth of the gastropod Turbo marmoratus using a sclerochronological method. The shells of an introduced population on Tahiti (pench Polynesia) are examined. The confirmation of age, based on a novel marking technique using a lead pencil, xgveals a daily rate of deposition within the growth rings..*:A new method of estimation of the growth parameters of the Von Bertalanffy model from the daily ring density (DRD) is described. The fit to the model allows the estimation of K = 0.32 year': and D, = 30.3 cm (D = diameter). INTRODUCTION The green snail, Turbo marmoratus, was introduced in w w Tahiti (French Polynesia) waters in 1967. It has thrived 15òo 14i" in the Polynesian archipelago, constituting a new 1 I resource whose stocks are exploited without particular knowledge of its biology. It has a current natural western Indo-Pacific distribution. A renewed interest in natural products has made it a luxury item, whose price has not ceased to rise over the last decade, while the world-wide stock is decreasing (Yamaguchi 1988a, 1991). Despite the economic value of this species, no growth studies have been undertaken in natura. To our knowledge, only the works of Yamaguchi (198823) deal with the biology and the ecology of Turbo marmoratus, and are based on observations in pools and aquaria in sub-tropical conditions. -

FRESHWATER PRAWN Macrobrachium Rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) (Crustacea: Decapoda) AQUACULTURE in FIJI: IMPROVING CULTURE STOCK QUALITY

FRESHWATER PRAWN Macrobrachium rosenbergii (De Man, 1879) (Crustacea: Decapoda) AQUACULTURE IN FIJI: IMPROVING CULTURE STOCK QUALITY by Shalini Singh A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Marine Science Copyright © 2011 by Shalini Singh School of Marine Studies Faculty of Science, Technology and Environment The University of the South Pacific July, 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my sponsors, the Australian Center for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and The University of the South Pacific (USP), for providing the opportunity to study for my master’s degree. My sincere thanks and gratitude to my supervisors, Dr. William Camargo (USP), Professor Peter Mather, Dr. Satya Nandlal, and Dr. David Hurwood (Queensland University of Technology - QUT) whose support, encouragement and guidance throughout this study is immensely appreciated. I am also very grateful to the following people for critically editing my thesis: Prof. Peter Mather, Dr. Satya Nandlal, Dr. William Camargo and Dr. Carmen Gonzales. Thank you all for your enormous support and guidance, which led to the successful completion of the project. I thank you all for allocating time from your very busy schedules to read my thesis. I would also like to thank the Fiji Fisheries Freshwater Aquaculture Section, particularly Naduruloulou Research Station, the staff for their immense effort and assistance, particularly in the hatchery and grow-out phases which could not have been successfully carried out without your support. I acknowledge the support, and assistance provided by ACIAR Project Officer Mr. Jone Vasuca and Kameli Lea for their immense effort during this project. -

Native Fish Species Boosting Brazilian's Aquaculture Development

Acta Fish. Aquat. Res. (2017) 5(1): 1-9 DOI 10.2312/ActaFish.2017.5.1.1-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Acta of Acta of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Native fish species boosting Brazilian’s aquaculture development Espécies nativas de peixes impulsionam o desenvolvimento da aquicultura brasileira Ulrich Saint-Paul Leibniz Center for Tropical Marine Research, Fahrenheitstr. 6, 28359 Bremen, Germany *Email: [email protected] Recebido: 26 de fevereiro de 2017 / Aceito: 26 de março de 2017 / Publicado: 27 de março de 2017 Abstract Brazil’s aquaculture production has Resumo A produção da aquicultura do Brasil increased rapidly during the last two decades, aumentou rapidamente nas últimas duas décadas, growing from basically zero in the 1980s to over passando de quase zero nos anos 80 para mais de one half million tons in 2014. The development meio milhão de toneladas em 2014. O started with introduced international species such desenvolvimento começou através da introdução as shrimp, tilapia, and carp in a very traditional de espécies internacionais, tais como o camarão, a way, but has shifted to an increasing share of tilápia e a carpa, de uma forma muito tradicional, native species and focus on the domestic market. mas mudou com o aporte crescente de espécies Actually 40 % of the total production is coming nativas e foco no mercado interno. Atualmente, from native species such tambaquí (Colossoma 40% da produção total provém de espécies nativas macropomum), tambacu (hybrid from female C. como tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum), macropomum and male Piaractus mesopotamicus). tambacu (híbrido de C. macropomum e macho Other species like pirarucu (Arapaima gigas) or Piaractus mesopotamicus). -

FAO Fisheries & Aquaculture

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles The Independent State of Samoa Part I Overview and main indicators 1. Country brief 2. General geographic and economic indicators 3. FAO Fisheries statistics Part II Narrative (2017) 4. Production sector Marine sub-sector Inland sub-sector Aquaculture sub-sector Recreational sub-sector Source of information United Nations Geospatial Information Section http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm 5. Post-harvest sector Imagery for continents and oceans reproduced from GEBCO, www.gebco.net Fish utilization Fish markets 6. Socio-economic contribution of the fishery sector Role of fisheries in the national economy Trade Food security Employment Rural development 7. Trends, issues and development Constraints and opportunities Government and non-government sector policies and development strategies Research, education and training Foreign aid 8. Institutional framework 9. Legal framework Regional and international legal framework 10. Annexes 11. References Additional information 12. FAO Thematic data bases 13. Publications 14. Meetings & News archive FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Part I Overview and main indicators Part I of the Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profile is compiled using the most up-to-date information available from the FAO Country briefs and Statistics programmes at the time of publication. The Country Brief and the FAO Fisheries Statistics provided in Part I may, however, have been prepared at different times, which would explain any inconsistencies. Country brief Prepared: May, 2018 Samoa has a population of 195 000 (2016), a land area of 2 935 km2, a coastline of 447 km, and an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 129 000 km2. -

A Viability Assessment of Commercial Aquaponics Systems in Iceland

A VIABILITY ASSESSMENT OF COMMERCIAL AQUAPONICS SYSTEMS IN ICELAND CHRISTOPHER WILLIAMS Supervisors: Magnus Thor Torfason Ragnheidur Thorarinsdottir Williams, Christopher Page 1 of 176 A Viability Assessment of Aquaponics in Iceland Christopher Williams 60 ECTS thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of a Magister Scientiarum degree in Environment and Natural Resources Supervisors: Magnus Thor Torfason Ragnheidur Thorarinsdottir Business Administration Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Iceland School of Environment and Natural Resources University of Iceland. Reykjavik, June 2017 Williams, Christopher Page 2 of 176 A Viability Assessment of Aquaponics in Iceland This thesis is an MS thesis project for the MSc degree at the Faculty of Business Administration, University of Iceland, Faculty of Social Sciences. © 2017 Christopher Williams The dissertation may not be reproduced without the permission of the author. Printing: Háskólaprent Reykjavik, 2017 Williams, Christopher Page 3 of 176 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to give the sincerest thanks to my advisors, Magnus Thor Torfason and Ragnheidur Thorarinsdottir for all their support and patience throughout this endeavor. They have opened so many opportunities for me in this journey and have given such incredible feedback and guidance. Without your help, none of this would be possible. The resources you have given me are invaluable and instrumental to completing my thesis. I would also like to give my thanks and gratitude to the wonderful staff and classmates I have had the pleasure of working with at the University. You have given me an enormous gift in letting me pursue work in something that I am personally passionate about and driven towards. I am so pleased to have had the pleasure of learning with you and sharing in ideas. -

Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles the Kingdom of Tonga

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Fisheries and for a world without hunger Aquaculture Department Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles The Kingdom of Tonga Part I Overview and main indicators 1. Country brief 2. General geographic and economic indicators 3. FAO Fisheries statistics Part II Narrative (2014) 4. Production sector Marine sub-sector Inland sub-sector Aquaculture sub-sector - NASO Recreational sub-sector Source of information United Nations Geospatial Information Section http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm 5. Post-harvest sector Imagery for continents and oceans reproduced from GEBCO, www.gebco.net Fish utilization Fish markets 6. Socio-economic contribution of the fishery sector Role of fisheries in the national economy Trade Food security Employment Rural development 7. Trends, issues and development Constraints and opportunities Government and non-government sector policies and development strategies Research, education and training Foreign aid 8. Institutional framework 9. Legal framework 10. Annexes 11. References Additional information 12. FAO Thematic data bases 13. Publications 14. Meetings & News archive FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department Part I Overview and main indicators Part I of the Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profile is compiled using the most up-to-date information available from the FAO Country briefs and Statistics programmes at the time of publication. The Country Brief and the FAO Fisheries Statistics provided in Part I may, however, have been prepared at different times, which would explain any inconsistencies. Country brief Current situation Tonga is an archipelagic nation of some 150 islands (36 of which are inhabited), representing a total land area of about 747 km2. -

Fisheries and Wildlife Research 1982

Fisheries and Wildlife Research 1982 Activities in the Divisions of Research for the Fiscal Year 1982 Edited by Paul H. Eschmeyer, Fisheries Thomas G. Scott, Wildlife Published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Printed by the U.S. Government Printing Office Denver, Colorado • 1983 •• , :e. ' • Noel Snyder, field biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Condor Research Center, carries a travel case containing a California condor chick from the chick's nesting site northeast of Los Angeles. The bird was captured in August, after biologists determined that the parents were not feeding the chick regularly. The chick was taken to the San Diego Wild Animal Park to begin a captive breeding program for this critically endangered species. Dr. Phil Ensley, veterinarian for the Zoological Society of San Diego, accompanied Dr. Snyder on the capture operation. Photo by H. K. Snyder. 11 Contents Foreword ...................................................... iv Tunison Laboratory of Fish Nutrition ........ 86 Fisheries and Wildlife Research .............. 1 National Reservoir Research Program . 88 Animal Damage Control ............................ 2 East Central Reservoir Investigations . 89 Denver Wildlife Research Center ............ 2 Multi-Outlet Reservoir Studies .................. 91 Southeast Reservoir Investigations .......... 93 Environmental Contaminant Evaluation 25 White River Reservoir Studies .................... 95 Columbia National Fisheries Research Seattle National Fishery Research Laboratory .............................................. -

GLOBEFISH Highlights, the GLOBEFISH Research Programme and the Commodity Updates

4th issue 2017 GLOBEFISH HIGHLIGHTSA QUARTERLY UPDATE ON WORLD SEAFOOD MARKETS October 2017 ISSUE, with Jan-Jun 2017 Statistics ABOUT GLOBEFISH GLOBEFISH forms part of the Products, Trade and Marketing Branch of the FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department and is part of the FISH INFOnetwork. It collects information from the main market areas in developed countries for the benefit of the world’s producers and exporters. Part of its services is an electronic databank and the distribution of information through the European Fish Price Report, the GLOBEFISH Highlights, the GLOBEFISH Research Programme and the Commodity Updates. The GLOBEFISH Highlights is based on information available in the databank, supplemented by market information from industry correspondents and from six regional services which form the FISH INFOnetwork: INFOFISH (Asia and the Pacific), INFOPESCA (Latin America and the Caribbean), INFOPECHE (Africa), INFOSAMAK (Arab countries), EUROFISH (Central and Eastern Europe) and INFOYU (China). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO.