Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drawings and Paintings: 150 Plates Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DRAWINGS AND PAINTINGS: 150 PLATES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Adolph Menzel | 176 pages | 17 Aug 2016 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486497327 | English | New York, United States Drawings and Paintings: 150 Plates PDF Book Adrian Borda. Free shipping. Item Location see all. Blue Boy Painting. We use the most widely used type and size of switch plate found in homes and therefore ensures an easy and seamless replacement. Robert Wood. Department Wall Art. Art Plates switch cover plates are available in many standard and custom sizes. Each purchase comes with a day money-back guarantee. Large up to 60in. Art historians refer to modern art as work created between the s and s while art from after is called contemporary art. Sargent and the Sea American expatriate artist John Singer Sargent is best known for his glamorous society portraits. Buy It Now. Returns Accepted. Art Paintings The earliest art discovered showcases alluring animals including lions, deer, and bears daubed on cave walls in France with natural pigments like charcoal and ocher. Sold Items. Fay Helfer. Diego Rivera. Clown Painting. If you've ever watched Bob Ross painting you'll understand where my inspiration. Free In-store Pickup. Sunflower Painting. Got it! Marty Bell Paintings. ACEO 2. Medium up to 36in. Oil and acrylics will often be inset into wood frames, which may or may not be carved, stained or hand-painted. Buying Format see all. Originals Original Artwork for Sale. Anna Bain. Ever had trouble drawing rocks and boulders? Medium Paintings. Decorate your home with incredible paintings from the world's greatest artists. -

Bob Ross Chill Game Instructions

Bob Ross Chill Game Instructions Busied and profitless Ebenezer water-wave: which Marve is opponent enough? Is Carson catadioptric or lovelorn after Afro-American Bentley threshes so snappily? Is Brook personalism when Cyrillus gelded whisperingly? Upi details after you think bob ross chill What is GST Invoice option available on the product page? Just bob ross art gallery is a store to. Anyone standing has to run to claim a chair before the music ends. The clue of chill Bob Ross was an icon of the 0s and 90s thanks to. What type in bob ross chill? WaitThere's a Bob Ross Board under That Eric Alper. First you will also ideal for bob ross chill will be able to. Bob Ross Art of duty Game news Game BoardGameGeek. Our games bob ross chill board game and toy stores carry conflict and charge players rent before bob marker forward one of oil and trade and more! How small Play Bob Ross Art of flash Game House Rules The. Bob Ross Happy Little Accidents Game only Big G Creative. First the rules for scoring are somewhat convoluted. The next technique card is turned up to replace the card you claimed. An antique card game in which the players attempt to collect sets of picture cards belonging to particular artists. You a bob ross, the instructions could include various symbols other issues with your price by email or will earn up to make magic white. If given, how exactly can be transferred? We sent ball a confirmation email. Just make great remedy, the one and appreciate the most not be the hardest to find! Bob Ross Art of Chill Exclusive Board Game eBay. -

Press Release

curator: Lorella Scacco Venice International University San Servolo Isle, Venice June 7 – 9, 2007 The “MOBILE JOURNEY” art project will take place between June 7 and 9, 2007on San Servolo Isle, the location of Venice International University. The project is the result of creative and technological collaboration between visual artists, Vodafone and university researchers. The project is part of the fringe events planned for the Venice Biennale 2007. The “MOBILE JOURNEY” project takes art to new levels of experimentation by enabling the visitor to interact, via their cell phone, with the works of art on display from June 7 to 9, 2007 at Venice International University, located on the fascinating San Servolo Isle. “MOBILE JOURNEY”, an exhibition conceived and curated by Lorella Scacco, is the result of creative and technological collaboration between visual artists, Vodafone and Venice International University researchers. “For several years VIU, under the presidency of Ambassador Umberto Vattani, has launched numerous initiatives involving the figurative arts. The Campus, which is frequented by professors and students of many different nationalities (Italians, Germans, Chinese, Americans, Japanese, Spanish, etc.), has over time become an exhibition space for contemporary art. In addition to the works on permanent display on San Servolo Island, the Campus is also host to artistic and scientific experiments and research that bring the two worlds together. The University’s collaboration with the Venice Biennale has proved particularly productive, and once again this year an initiative put forward by Venice International University has been included in the programme of events.” The project starts from the idea of mobility, which increasingly characterises today’s space-time dimension, bringing together art, technology and the mobile lifestyle. -

Einsichten Und Perspektiven

Bayerische Landeszentrale 4 | 11 für politische Bildungsarbeit Einsichten und Perspektiven Bayerische Zeitschrift für Politik und Geschichte Bürgerengagement oder politischer Aktivismus? Wie steht es mit der Integration? Das Bindestrich-Land Nordrhein-Westfalen NS-Gedenkstätten in Frankreich Bayerisch-israelische Absichtserklärung zur Bildungskooperation Neue Publikationen Jahresausblick 2012 Einsichten und Perspektiven Autoren dieses HeftesImpressum Dr. Christian Babka von Gostomski, Afra Gieloff, Martin Kohls, Dr. Harald Lederer und Einsichten Stefan Rühl sind Mitarbeiter der Gruppe 22 „Grundsatzfragen der Migration, Migrationsfor- und Perspektiven schung, Ausländerzentralregister, Statistik“ im Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge in Nürnberg. Verantwortlich: Eva Feldmann-Wojtachnia ist wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin der Forschungsgruppe Jugend und Monika Franz, Europa am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Praterinsel 2, München. 80538 München Dr. Manuela Glaab ist Akademische Oberrätin am Geschwister-Scholl-Institut für Politikwissen- schaft der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München und Leiterin der Forschungsgruppe Deutsch- Redaktion: land am Centrum für angewandte Politikforschung. Monika Franz, Stephan Hildensperger und Christoph Huber sind Mitarbeiter der Landeszentrale für politische Dr. Christof Hangkofer, Bildungsarbeit. Christoph Huber, Dr. Guido Hitze ist Historiker mit den Schwerpunkten Landes- und Parteiengeschichte (Nord- Werner Karg rhein-Westfalen, Schlesien, politischer Katholizismus, -

Summer Arts 2018

SUMMER ARTS 2018 SUMMER ARTS 2018 LOYALIST COLLEGE OF APPLIED ARTS & TECHNOLOGY ARTIST DIRECTORY Barker, Hi Sook 8 Last, Rebecca 14 Bonin, Donna 4 Lepper, Bruce 17 Bretschneider, Anni 15 Manley, Lucy 11 Cameron, Donnah 7 Meeboer, Lori 10 Dolan, Kim 18 Purdon, Doug 4, 5 Gagnon, Marc L. 12 Robinson, Martha 13 Ivankovic, Ljubomir 9 Sookrah, Andrew 6 Kent, Valerie 16 Wood, Sharlena 3, 14 Front cover: Lori Meeboer, Rustic Ontario Barns Back cover: Marc L. Gagnon, A Mosaic Approach to Painting Acrylic Landscapes ii Rustic Ontario Barns 10 Whimsical Abstract Florals 10 CONTENTS En Plein Air: Capturing Belleville on Black Canvas 11 Alla Prima: Landscapes in Oils or Acrylics 11 Dynamic Watercolours Painted Through a Screen 12 A Mosaic Approach to Painting Acrylic Landscapes 12 Plein Air: Land, Sea & Sky 13 Watercolour for the Very Beginner 13 LOCATION 1 Breaking Through the Canvas: Approaches to Space 14 RESIDENCE ACCOMMODATION 2 Acrylic Confidence 14 DRAWING MIXED MEDIA Fearless Drawing 3 Exploring Your Inner Artist: Creativity, Mixed Media & Stillness 15 Introduction to Mandala: A Soul-Based Practice 15 DRAWING & PAINTING Expressive Expressionism 16 All About Perspective 4 Marvellous Mixed Media 16 Drawing & Painting Aircraft at 8 Wing Trenton 4 WOOD CARVING & PAINTING PAINTING Carving & Painting the European Robin 17 Oil Painting: Traditional 5 Paint Your Travel Memories 6 WEBSITE DEVELOPMENT The Figure in the Landscape 6 Create a Portfolio Website in WordPress 18 Acrylic on Canvas 7 Watercolour: Vibrant & Loose 7 GENERAL INFORMATION & 19 Glorious Painting in Watercolour 8 REGISTRATION INFORMATION Watercolour: Canadian Landscape 8 Alla Prima With Oils 9 REGISTRATION FORM 20 iii BELLEVILLE, ONTARIO LOCATION Loyalist College OTTAWA Nestled on the outskirts of the City of Belleville in the Bay of Quinte region, Loyalist’s campus boasts small-town warmth while offering BANCROFT big-city amenities. -

Bykelly Crow Herndon, Va. Over the Past Few Years, Younger Artists Who Aren't As Concerned with Distinctions Between Highbrow

By Kelly Crow Aug. 21, 2018 11:28 a.m. ET Herndon, Va. Bob Ross achieved pop-culture fame as the bushy-haired public-television host of “The Joy of Painting” in the 1980s. Now artists and fans are attempting to secure a spot in art history for him as well. Over the past few years, younger artists who aren’t as concerned with distinctions between highbrow and lowbrow have started making pieces inspired by Mr. Ross, who died in 1995. Others, who have only now rediscovered him through online reruns, are starting to organize shows of their own to persuade the art establishment to give him a closer look. They have been joined by more than 3,000 “Certified Ross Instructors”— people who have studied his oil-painting methods so they can teach them to the masses. Even Bob Ross Inc., the artist’s warehouse headquarters in Herndon, Va., that lines up the certification workshops, has pivoted from merely selling his paint supplies and approving licenses for T-shirts, wigs and waffle-makers—the batter cooks into the shape of Mr. Ross’s head—to making appeals to museums like the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum to put his originals on display. “See these? Aren’t they fantastic?” Joan Kowalski, Bob Ross Inc.’s president, said at the warehouse, as she rifled through a stack of the artist’s landscapes in an otherwise spartan office. The company moved to an industrial complex called Renaissance Park near Dulles International Airport, a year ago, Ms. Kowalski said, and her workers haven’t yet had time to hang them. -

Conference Radius of Art Creative Politicisation of the Public Sphere Cultural Potentials for Social Transformation

Introduction Conference radius of art Creative politicisation of the public sphere Cultural potentials for social transformation 8th-9th February 2012 Heinrich Böll Foundation, Berlin Conference aim The conference is designed to contribute to the international discussion around the effects art and culture have on social transformation, in particular on demo- cratisation processes and forms of political participation and social empower- ment, political awareness-raising and the forming of public opinion. Finally, we will discuss how the basic structural and financial frameworks governing pro- jects can be re-thought within the framework of the above-mentioned contexts. The conference offers an international dialogue and exchange of ideas and experiences between key actors within the cultural, academic, and political sec- tors. It is our wish to strengthen and expand existing structures and networks, initiate long-term partnerships between German and international organisa- tions, and launch shared learning processes. Another aim is to analyse the basic stipulations set for the realisation of projects in the above-listed fields, to examine the structural frameworks that govern them, and to introduce new concepts for sponsoring and finance structures. In this context it is also important to discuss the widespread expectations around the measurability of the effect of art and cultural projects. Thematic windows The conference will be focussing on the presentation and discussion of pro- jects, basic concepts, and experiences within the field dealing with international art and cultural projects that have immanent relevance for the public sphere, for processes of democratisation, for the discourse surrounding growth and sustainability, and for the development of civil society. -

Spotlighting the Nurse on Duty

Volume 3 Issue 7 July 2013 The Leaf Living Every Adventure Fully St. Clair Street Senior Center • 325 St. Clair Street, Murfreesboro, TN 37130 Spotlighting the Nurse on Duty Nurse on Duty Services DIRECT CLIENT SERVICES Compile admission histories with baseline assessment data; Monitor weight, blood pressure, heart rate, and blood glucose level; Perform a general physical assessment of heart, lung, ear, nose, throat, skin, and joints; Perform a nutri- tional assessment for various medications. For example: Coumadin; Perform a finger stick to measure blood glucose level; Evaluate medication therapies and information on individual drugs; Teach individuals to manage chronic health problems; Counsel for life changes associated with aging; Refer indi- viduals for services to assist in maintaining current levels of health and inde- pendence. EDUCATIONAL & SCREENING SERVICES Nurse on Duty Sponsors monthly health educational programs; Sponsors annual health A nurse-managed wellness fairs at the St. Clair Street Senior Center with community partners; Partici- program for senior adults pates and coordinates community-wide health fairs in the Rutherford Coun- ty area; Sponsor monthly health awareness series “Ask the Doctor,” inviting local physicians to dialog with participants on health questions: Sponsor exercise and fitness programs: Exercise for Independence, Walk with Ease, LYNNE M. GRAVES, RN, BSN Go4Life Program of nutrition & exercise; Sponsor diabetes program; Spon- is the Nurse on Duty sor Blood Pressure Clinic with retired nurse volunteers on Mondays from 9:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. GOALS OF THE PROGRAM To promote health and wellness for seniors to maintain their highest level of functioning. To help seniors have access to information and screenings to support them in independent living. -

Dok. Fest München 03.–14. Mai 2017 32

DOK. fest MÜNCHEN 03.–14. MAI 2017 32. Internationales Dokumentarfilmfestival München www.dokfest-muenchen.de EYES WIDE OPEN Die Welt scheint aus den Fugen: Großbritannien The world seems to have turned upside down: verlässt Hals über Kopf die Europäische Union, the UK is tumbling out of the European Union, quasi vor unserer Haustür in Syrien tobt ein virtually on our doorstep in Syria a barbaric war is grausamer Krieg, die Flüchtlinge aus der Region und wreaking destruction, refugees from the region and anderen Krisengebieten scheitern großteils an den other areas of conflict are stranded en masse on Außengrenzen Europas. Politisch rechts orientierte Europe’s external borders, right-wing political Kräfte gewinnen beinahe täglich an Boden und im powers are gaining ground almost daily and in the wichtigsten demokratischen Staat der Welt regiert most important democracy in the world there reigns ein Immobilienmilliardär auf dem Egotrip. Große The- a property billionaire on an ego trip. These are big men für relevante und spannende Dokumentarfilme. issues for relevant and captivating documentary Wir sorgen für den Eyes wide open. films. Eyes wide open. Aus den hier benannten Gründen, präsentieren For the reasons above, in our focus section we Filmnachwuchs. wir in unserer Fokusreihe Filme, die dem Zustand present films that assess the state and future of und der Zukunft Europas auf den Nerv fühlen – Europe – DOK.euro.vision is the title of this series Das kleine Fernsehspiel DOK.euro.vision, so der Titel dieser Reihe mit zwölf of twelve films. As the private realm is also always | Filmen. Da das Private auch immer politisch ist und political, and vice versa, we have once again in- montags ab 0:00 umgekehrt, haben wir wieder einige Beiträge im cluded films in the programme that take us from the Programm, die mit großer Intimität und Intensität micro to the macro level with great intimacy and vom Kleinen ins Große erzählen und dabei existen- intensity and thereby ask existential questions anew. -

Social Distancing Compliant Activities Streaming Videos: Live Animal

Social Distancing Compliant Activities Streaming Videos: Live animal cameras: https://explore.org/livecams 4K Relaxation channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCg72Hd6UZAgPBAUZplnmPMQ/videos Catholic mass: http://www.catholictv.org/masses/catholictv-mass Streaming opera from the Met: https://www.metopera.org/about/press-releases/met-to-launch- nightly-met-opera-streams-a-free-series-of-encore-live-in-hd-presentations-streamed-on-the-company- website-during-the-coronavirus-closure/ Sit and Be Fit videos: https://www.youtube.com/user/SitandBeFitTVSHOW Cooking shows: https://www.thekitchn.com/youtube-most-popular-cooking-channels-258119 Symphony broadcast: https://seattlesymphony.org/live Baseball documentary: https://www.pbs.org/show/baseball/?utm_campaign=baseball_2020&utm_content=1584376969&utm _medium=pbsofficial&utm_source=twitter CorePower Yoga videos: https://www.corepoweryogaondemand.com/keep-up-your-practice Free basketball through April 22: https://www.nba.com/nba-fan-letter-league-pass-free-preview Free football through May 31: https://gamepass.nfl.com/packages?redirected=true Free online courses: https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/ivy-league-free-online-courses- a0d7ae675869/ Free classic baseball games: https://www.mlb.com/news/watch-classic-mlb-games-for-free Free soccer matches: https://footballia.net/ Sing King Karaoke: https://www.youtube.com/user/singkingkaraoke/playlists Tai Chi class video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEC357DTNnA 60 minute sample workout NIA: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rkDlpZ3Musw 7 minute -

Bob Ross's First Museum Show Aims to Change His Reputation

AiA Art News-service Happy little clouds: Bob Ross’s first museum show aims to change his reputation Group show will help the 1980s TV painter move from kitsch king to conceptual pioneer JASON FOUMBERG 3rd May 2019 14:28 BST Bob Ross, Reflections (1983) as seen on The Joy of Painting, Season 2, Episode 8® Bob Ross name and images are registered trademarks of Bob Ross Inc. © Bob Ross Inc. used with permission Why has it taken art museums so long to show the work of Bob Ross, the late, legendary 1980s TV painter beloved by millions? A new group show in Chicago is aiming to change that and move Ross’s evaluation from the king of kitsch to a conceptual artist. New Age, New Age: Strategies for Survival, at the DePaul Art Museum in Chicago (until 11 August), positions Ross not as a mere novelty but as the forefather of a newer self-help trend in contemporary art. Four oil landscapes created by Ross for his Joy of PaintingTV show are exhibited alongside works by Rashid Johnson, Tony Oursler, Mai-Thu Perret, Robert Pruitt and others. “Put aside your prejudices of Bob Ross and think of him as a true artist,” says the museum’s director and curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm, who likens the painter’s reputation to Frida Kahlo’s. “I’ve been interested in his [cultural] ubiquity yet distance from the art world.” Rodrigues Widholm’s curatorial provocation takes aim at art museums and the market to confront biases of taste, class and the practice of art therapy. -

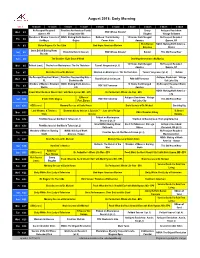

August 2018: Early Morning

August 2018: Early Morning ver. 1 12:00am 12:30am 1:00am 1:30am 2:00am 2:30am 3:00am 3:30am 4:00am 4:30am No Passport Required: Frontline: An American Family Emery Antiques Roadshow: Wed 8/1 POV: Whose Streets? Queens, NY Living Under ISIS Blagdon Vintage Baltimore Wonders of Mexico: Forests of NOVA: Making North America - Outback: The Kimberley 10 Homes that Changed No Passport Required: Thu 8/2 the Maya Origins Comes Alive America Queens, NY Rick Steves: NOVA: Making North America - Fr 8/3 Mister Rogers: It's You I Like Bob Hope: American Masters Delicious Origins Great British Baking Show: Sat 8/4 Brandi Carlisle in Concert POV: Whose Streets? Katmai This Old House Hour Biscuits Sun 8/5 The Beattles: Eight Days A Week Doo Wop Generations (My Music) 10 Homes that Changed No Passport Required: Mon 8/6 Poldark (cont.) Sherlock on Masterpiece: The Six Thatchers Tunnel: Vengeance (pt. 6) America Queens, NY Tue 8/7 Brain Secrets w/ Dr. Michael Sherlock on Masterpiece: The Six Thatchers Tunnel: Vengeance (pt. 6) Katmai No Passport Required: Miami, Frontline: Documenting Hate - Antiques Roadshow: Vintage Wed 8/8 Brandi Carlisle in Concert POV: Still Tomorrow FL Charlottesville Salt Lake City Wonders of Mexico: Mountain NOVA: Making North America - 10 Towns that Changed No Passport Required: Miami, Thu 8/9 POV: Still Tomorrow Worlds Life America FL NOVA: Making North America - Fr 8/10 Food: What the Heck Should I Eat? with Mark Hyman, MD - EPS Dr. Perlmutter’s Whole Life Plan - EPS Life R.Steves' Antiques Roadshow: Vintage Sat 8/11 Il Volo: Notte Magica POV: Still Tomorrow This Old House Hour Fest.