The Virginia State Rail Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shenandoah Telecommunications Company

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from__________ to __________ Commission File No.: 000-09881 SHENANDOAH TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 54-1162807 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 500 Shentel Way, Edinburg, Virginia 22824 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (540) 984-4141 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) OF THE ACT: Common Stock (No Par Value) SHEN NASDAQ Global Select Market 49,932,073 (The number of shares of the registrant's common stock outstanding on (Title of Class) (Trading Symbol) (Name of Exchange on which Registered) February 23, 2021) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(G) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Note - Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act from their obligations under those Sections. -

Conference Agenda

Table of Contents The Hilton Norfolk the Main Hotel Floor Plan ....................................................... 2 Spring Conference Schedule .................................................................................. 3 VGFOA Executive Board 2017-2018 ....................................................................... 7 List of VGFOA Past Presidents ............................................................................... 8 List of CPFO’s ........................................................................................................ 10 List of VGFOA and Radford University GNAC Certificate Recipients ............... 11 GFOA Update ...................................................................................................... 16 U.S. Economic Update ......................................................................................... 17 Virginia Economic Forecast ................................................................................ 18 Speed Networking ................................................................................................ 19 Keynote Session - The Number One Thing That Holds Us Back ......................... 20 GASB Update ...................................................................................................... 21 VRS - Employer Update ....................................................................................... 22 Revenue and Expense Recognition ..................................................................... 23 Cyber Security - Risk -

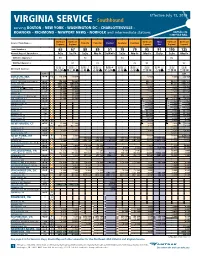

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Issue of Play on October 4 & 5 at the "The 6 :,53"

I the 'It, 980 6:53 OCTOBER !li AMTRAK... ... now serving BRYAN and LOVELAND ... returns to INDIA,NAPOLIS then turns em away Amtrak's LAKE SHORE LIMITED With appropriate "first trip" is now making regular stops inaugural festivities, Amtrak every day at BRYAN in north introduced daily operation of western Ohio. The westbound its new HOOSIER STATE on the train stops at 11:34am and 1st of October between IND the eastbound train stops at IANAPOLIS and CHICAGO. Sev 8:15pm. eral OARP members were on the Amtrak's SHENANDOAH inaugural trip, including Ray is now stopping daily at a Kline, Dave Marshall and Nick new station stop in suburban Noe. Complimentary champagne Cincinnati. The eastbound was served to all passengers SHENANDOAH stops at LOVELAND and Amtrak public affairs at 7:09pm and the westbound representatives passed out train stops at 8:15am. A m- Amtrak literature. One of trak began both new stops on the Amtrak reps was also pas Sunday, October 26th. Sev sing out OARP brochures! [We eral OARP members were on don't miss an opportunity!] hand at both stations as the Our members reported that the "first trains" rolled in. inaugural round trip was a OARP has supported both new good one, with on-time oper station stops and we are ation the whole way. Tracks glad they have finally come permit 70mph speeds much of about. Both communities are the way and the only rough supportive of their new Am track was noted near Chicago. trak service. How To Find Amtrak held another in its The Station Maps for both series of FAMILY DAYS with BRYAN qnd LOVELAND will be much equipment on public dis fopnd' inside this issue of play on October 4 & 5 at the "the 6 :,53". -

Northeast Corridor Chase, Maryland January 4, 1987

PB88-916301 NATIONAL TRANSPORT SAFETY BOARD WASHINGTON, D.C. 20594 RAILROAD ACCIDENT REPORT REAR-END COLLISION OF AMTRAK PASSENGER TRAIN 94, THE COLONIAL AND CONSOLIDATED RAIL CORPORATION FREIGHT TRAIN ENS-121, ON THE NORTHEAST CORRIDOR CHASE, MARYLAND JANUARY 4, 1987 NTSB/RAR-88/01 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT TECHNICAL REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE 1. Report No. 2.Government Accession No. 3.Recipient's Catalog No. NTSB/RAR-88/01 . PB88-916301 Title and Subtitle Railroad Accident Report^ 5-Report Date Rear-end Collision of'*Amtrak Passenger Train 949 the January 25, 1988 Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight -Performing Organization Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Code Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987 -Performing Organization 7. "Author(s) ~~ Report No. Performing Organization Name and Address 10.Work Unit No. National Transportation Safety Board Bureau of Accident Investigation .Contract or Grant No. Washington, D.C. 20594 k3-Type of Report and Period Covered 12.Sponsoring Agency Name and Address Iroad Accident Report lanuary 4, 1987 NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SAFETY BOARD Washington, D. C. 20594 1*+.Sponsoring Agency Code 15-Supplementary Notes 16 Abstract About 1:16 p.m., eastern standard time, on January 4, 1987, northbound Conrail train ENS -121 departed Bay View yard at Baltimore, Mary1 and, on track 1. The train consisted of three diesel-electric freight locomotive units, all under power and manned by an engineer and a brakeman. Almost simultaneously, northbound Amtrak train 94 departed Pennsylvania Station in Baltimore. Train 94 consisted of two electric locomotive units, nine coaches, and three food service cars. In addition to an engineer, conductor, and three assistant conductors, there were seven Amtrak service employees and about 660 passengers on the train. -

Phase I National Gateway Clearance Initiative Documentation

Lead Agencies: Environmental Assessment and Section 4(f) Evaluation Cooperating Agencies: Phase I National Gateway Clearance Initiative epartment of Transportation Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 42 U.S.C. 4332(2)(C) September 7, 2010 Pennsylvania Department of Transportation West Virginia Department of Transportation Table of Contents 1. Summary 1 1.1 History of the Initiative 1 1.2 Logical Termini 7 1.3 Need and Purpose 9 1.4 Summary of Impacts and Mitigation 11 1.5 Agency Coordination and Public Involvement 18 1.5.1 Agency Coordination 18 1.5.2 Public Involvement 21 2. Need and Purpose of the Action 22 3. Context of the Action and Development of Alternatives 25 3.1 Overview 25 3.1.1 No Build Alternative 25 3.1.2 Proposed Action 26 3.2 Bridge Removal 26 3.3 Bridge Raising 27 3.4 Bridge Modification 27 3.5 Tunnel Liner Modification 28 3.6 Tunnel Open Cut 28 3.7 Excess Material Disposal 29 3.8 Grade Adjustment 29 3.9 Grade Crossing Closures/Modifications 30 3.10 Other Aspects 30 3.10.1 Interlocking 30 3.10.2 Modal Hubs 30 4. Impacts and Mitigation 31 4.1 Corridor-Wide Impacts 31 i Table of Contents 4.1.1 Right-of-Way 31 4.1.2 Community and Socio-Economic 31 4.1.2.1 Community Cohesion 31 4.1.2.2 Employment Opportunity 31 4.1.2.3 Environmental Justice 34 4.1.2.4 Public Health and Safety 35 4.1.3 Traffic 36 4.1.3.1 Maintenance of Traffic 36 4.1.3.2 Congestion Reduction 37 4.1.4 General Conformity Analysis 37 4.1.4.1 Regulatory Background 37 4.1.4.2 Evaluation 39 4.1.4.3 Construction Emissions 40 4.1.4.4 Conclusion -

History of the Pere Marquette Railway

History of the Pere Marquette Railway Local History at the St. Thomas Public Library 1900: The Pere Marquette Railroad (PM) is formed by merging three small railroads in the United States: Chicago & West Michigan; Flint & Pere Marquette; and the Detroit, Grand Rapids & Western Railways. The PM is named after Père Jacques Marquette, the French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan’s first European settlement, Sault St. Marie. 1901: Car ferry Pere Marquette 17 is placed in Lake Michigan service. The PM used car ferries on Lake Michigan to avoid the terminal and interchange delays in the area. Later, they were used on Lake Erie, the Detroit River, and in Port Huron. Car Ferry Pere Marquette 17 1902: Car ferry (first) Pere Marquette 18 is placed into Lake Michigan service. January 1903: PM acquires the Lake Erie & Detroit River Railway (LE&DRR), with main lines running from Walkerville, Windsor to St. Thomas, Ontario, as well as from Sarnia to Chatham and Erieau. This begins the Pere Marquette’s presence in Canada. 1904: The Pere Marquette secures running rights from Buffalo, New York and Niagara Falls, New York over the Canadian Southern railway lines to reach St. Thomas, where the PM’s main Canadian facilities will be located. 1905: Shop facilities are constructed in St. Thomas. December 1905: The first receivership begins, meaning that the company is controlled by others in order to make the best decision based on its finances, whether that is stabilizing or selling the company. The Pere Marquette has struggled financially for much of its operating life, and will continue to do so. -

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report Genesee & Wyoming Inc.*owns or leases 122 freight railroads worldwide that are organized into 10 operating regions with approximately 7,300 employees and 3,000 customers. * The terms “Genesee & Wyoming,” “G&W,” “the company,” “we,” “our,” and “us” refer collectively to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. and its subsidiaries and affiliated companies. Financial Highlights Years Ended December 31 (In thousands, except per share amounts) 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Statement of Operations Data Operating revenues $874,916 $1,568,643 $1,639,012 $2,000,401 $2,001,527 Operating income 190,322 380,188 421,571 384,261 289,612 Net income 52,433 271,296 261,006 225,037 141,096 Net income attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 48,058 269,157 260,755 225,037 141,137 Diluted earnings per common share attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. common stockholders: Diluted earnings per common share (EPS) $1.02 $4.79 $4.58 $3.89 $2.42 Weighted average shares - Diluted 51,316 56,679 56,972 57,848 58,256 Balance Sheet Data as of Period End Total assets $5,226,115 $5,319,821 $5,595,753 $6,703,082 $7,634,958 Total debt 1,858,135 1,624,712 1,615,449 2,281,751 2,359,453 Total equity 1,500,462 2,149,070 2,357,980 2,519,461 3,187,121 Operating Revenues Operating Income Net Income Diluted Earnings ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) 421.61,2 Per Common Share 2 2,001.5 401.6 1 $2,000 2,000.4 $400 394.12 $275 271.3 $5.00 1 2 4.79 1 374.3 1 380.21 384.3 261.0 4.581 1,800 250 4.50 350 1,639.0 225.01 225 2 1 1,600 233.5 4.00 2 3.89 1,568.6 4.10 2 300 2 200 213.9 213.3 2 3.78 2 1,400 1 3.50 3.69 289.6 183.32 3.142 250 175 1,200 3.00 211. -

A RIGHT-TO-WORK MODEL, the UNIONIZATION of FAIRFAX COUNTY GOVERNMENT WORKERS By

A RIGHT-TO-WORK MODEL, THE UNIONIZATION OF FAIRFAX COUNTY GOVERNMENT WORKERS by Ann M. Johnson A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA A Right-to-Work Model, the Unionization of Fairfax County Government Workers A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Ann M. Johnson Master of Arts University of North Carolina at Charlotte, 1995 Bachelor of Arts Hamilton College, 1986 Director: Dae Young Kim, Professor Department of Sociology Spring Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA COPYRIGHT 2017 ANN M. JOHNSON ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Dedication This is dedicated to the memory of my beloved parents, Wilfred and Ailein Faulkner, and sister, Dawn “Alex” Arkell. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the staff and members of the Fairfax County Government Employee Union who generously gave of their time and expertise: Kevin Jones, Jessica Brown, LaNoral -

Great Lakes Maritime Institute

JANUARY - FEBRUARY, 1978 Volume XXVII; Number 1 GREAT LAKES MARITIME INSTITUTE DOSSIN GREAT LAKES MUSEUM Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan 48207 JAN/FEB, 1978 Page 2 MEMBERSHIP NOTES Welcome to 1978! A brand new year, a brand new slate, and a brand new outlook. It is going to be difficult to keep up with the pace set in 1977, but the continued success of the Institute demands that we not just meet, but surpass last year. At the close of the year our member ship had grown to approaching 1,50C. pretty good for an organization that had 97 members in 1959...but this year we’ll shoot for 1,600. It’ll take a lot of work, and you’ll have to help, but you always have, so we should make it. Telescope production last year produced a total of 244 pages, and in addition to that we produced the FITZGERALD book with 60 pages. For the uninitiated, this means your Editor typed, then Varityped 608 pages. This much production takes a lot of time, but we are going to do something about it, and we’ll have an announcement to make perhaps as early as the next issue. Not only will what we have planned result in far less work to getting Telescope out, but it will produce a far better product. Yes, 1977 was a good year...but 1978 looks better. MEETING NOTICES Regular membership meetings are scheduled for January 27, March 31, and May 19 (early to avoid Memorial Day weekend). All meetings will be at the Dossin Museum at 8:00 PM. -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

1.6 Million Square Feet of Distribution Center Space

1.6 MILLION SQUARE FEET OF DISTRIBUTION CENTER SPACE P ORT S TORAGE & & T RAN sp ORTATION We Offer Our Clients: Foreign Trade Zone, Vendor Compliance Management, Inventory Control, Vendor Managed Inventory, Order Fulfillment and Product Modification. Now what can we do for your business? Givens.com 69 PORT STORAGE & TRANSPORTATION Cold Storage ................................................................. 69 Warehousing ................................................................. 70 Air Services and Airports ...................................................... 79 Motor Carrier Services ........................................................ 83 Passenger Cruise Service ...................................................... 83 Railroad Services ............................................................. 84 Towing and Barge Services .................................................... 88 ORTATION sp RAN T & & TORAGE S ORT P PORT STORAGE & TRANSPORTATION STORAGE/WAREHOUSE COLD STORAGE n PREFERRED FREEZER SERVICES Preferred Freezer Services is a leading temperature controlled, full service warehousing and distribution company in the United States. In September of 2007, Preferred Freezer Services of Norfolk opened its doors, following the company’s nationwide expansion plan. The facility boasts freezer capacity of 7.9 million cubic feet and nearly 24,000-sq. ft. of refrigerated loading/ unloading dock with 19 dock doors. Preferred Freezer Services of Norfolk has designated inspection areas for USDA, FDA and USDC and is HAACP certified.