Maryland Historical Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shenandoah Telecommunications Company

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D. C. 20549 FORM 10-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from__________ to __________ Commission File No.: 000-09881 SHENANDOAH TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMPANY (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 54-1162807 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 500 Shentel Way, Edinburg, Virginia 22824 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (540) 984-4141 (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(B) OF THE ACT: Common Stock (No Par Value) SHEN NASDAQ Global Select Market 49,932,073 (The number of shares of the registrant's common stock outstanding on (Title of Class) (Trading Symbol) (Name of Exchange on which Registered) February 23, 2021) SECURITIES REGISTERED PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(G) OF THE ACT: NONE Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Note - Checking the box above will not relieve any registrant required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act from their obligations under those Sections. -

Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020

Maryland State Archives Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 Annual Report of the State Archivist to the Governor and General Assembly (State Government Article, § 9-1007(d)) Timothy D. Baker State Archivist and Commissioner of Land Patents August 2020 Maryland State Archives 350 Rowe Boulevard · Annapolis, MD 21401 410-260-6400 · http://msa.maryland.gov MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 Table of Contents Agency Organization & Overview of Activities . 3 Hall of Records Commission Meeting of November 14, 2019 Agenda . 27 Minutes . .47 Chronology of Staff Events. .55 Records Retention Schedules . .65 Disposal Certificate Approvals . .. .70 Records Received . .78 Special Collections Received . 92 Hall of Records Commission Meeting of May 08, 2020 Agenda . .93 Minutes . .115 Chronology of Staff Activities . .121 Records Retention Schedules . .129 Disposal Certificate Approvals . 132 Records Received . 141 Special Collections Received . .. 158 Maryland Commission on Artistic Property Meeting of Agenda . 159 Minutes . 163 MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 This Page Left Blank 2 MSA Annual Report Fiscal Year 2020 STATE ARCHIVES ANNUAL REPORT FY 2020 OVERVIEW · Hall of Records Commission Agenda, Fall 2019 · Hall of Records Commission Agenda, Spring 2020 · Commission on Artistic Property Agenda, Fall 2019 The State Archives was created in 1935 as the Hall of Records and reorganized under its present name in 1984 (Chapter 286, Acts of 1984). Upon that reorganization the Commission on Artistic Property was made part of the State Archives. As Maryland's historical agency, the State Archives is the central depository for government records of permanent value. -

DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds Gavel.) Good Afternoon and Welcome to the National Press Club. My Name Is Donna Leinwand. I'm a Repor

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JEFF IDELSON SUBJECT: JEFF IDELSON, PRESIDENT OF THE NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME, IS SCHEDULED TO SPEAK AT A NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON MAY 11. HALL OF FAME THIRD BASEMAN BROOKS ROBINSON WILL BE A SPECIAL GUEST. MODERATOR: DONNA LEINWAND, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 1:00 P.M. EDT DATE: MONDAY, MAY 11, 2009 (C) COPYRIGHT 2009, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB. RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. DONNA LEINWAND: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Donna Leinwand. I’m a reporter at USA Today and I’m president of the National Press Club. We’re the world’s leading professional organization for journalists and are committed to a future of journalism by providing informative programming, journalism education and fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. On behalf of our 3,500 members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speaker and our guests in the audience today. I’d also like to welcome those of you who are watching us on C-Span. We’re looking forward to today’s speech, and afterwards, I’ll ask as many questions from the audience as time permits. -

Issue of Play on October 4 & 5 at the "The 6 :,53"

I the 'It, 980 6:53 OCTOBER !li AMTRAK... ... now serving BRYAN and LOVELAND ... returns to INDIA,NAPOLIS then turns em away Amtrak's LAKE SHORE LIMITED With appropriate "first trip" is now making regular stops inaugural festivities, Amtrak every day at BRYAN in north introduced daily operation of western Ohio. The westbound its new HOOSIER STATE on the train stops at 11:34am and 1st of October between IND the eastbound train stops at IANAPOLIS and CHICAGO. Sev 8:15pm. eral OARP members were on the Amtrak's SHENANDOAH inaugural trip, including Ray is now stopping daily at a Kline, Dave Marshall and Nick new station stop in suburban Noe. Complimentary champagne Cincinnati. The eastbound was served to all passengers SHENANDOAH stops at LOVELAND and Amtrak public affairs at 7:09pm and the westbound representatives passed out train stops at 8:15am. A m- Amtrak literature. One of trak began both new stops on the Amtrak reps was also pas Sunday, October 26th. Sev sing out OARP brochures! [We eral OARP members were on don't miss an opportunity!] hand at both stations as the Our members reported that the "first trains" rolled in. inaugural round trip was a OARP has supported both new good one, with on-time oper station stops and we are ation the whole way. Tracks glad they have finally come permit 70mph speeds much of about. Both communities are the way and the only rough supportive of their new Am track was noted near Chicago. trak service. How To Find Amtrak held another in its The Station Maps for both series of FAMILY DAYS with BRYAN qnd LOVELAND will be much equipment on public dis fopnd' inside this issue of play on October 4 & 5 at the "the 6 :,53". -

2008 Hornet Volleyball Notes

2008 Hornet Volleyball Notes October 31 - November 2 vs. Morgan State (10/31), vs. Quinnipiac (11/1), vs. Coppin State (11/2) Contact: Brett Kahn -- Office Phone: (302) 857-6239 -- Cell Phone: (215) 431-2780 -- E-mail: [email protected] nnDate Opponent/Tournament Time THIS WEEK IN DELAWARE STATE VOLLEYBALL Aug. 29 Fairleigh Dickinson (1) L, 0-3 Aug. 29 South Dakota (1) L, 1-3 Aug. 30 Wofford (1) W, 3-2 Delaware State (11-10, 5-3) vs. Morgan State (3-22, 2-6) -- Friday, October 31 -- Memorial Hall Aug. 30 South Carolina State (1) W, 3-0 -- 7 p.m. Live Stats: dsuhornets.com Sep. 5 Fairleigh Dickinson (2) L, 2-3 Sep. 6 Lafayette (2) L, 0-3 Sep. 6 St. Peter’s (2) W, 3-1 Delaware State (11-10, 5-3) vs. Quinnipiac (3-25, 0-4) -- Saturday, November 1 -- Memorial Hall -- 9 a.m. Sep. 12 George Washington (3) L, 0-3 Live Stats: dsuhornets.com Sep. 13 Rider (3) L, 0-3 Sep. 23 Delaware L, 0-3 Delaware State (11-10, 5-3) vs. Coppin State (0-21, 0-8) -- Sunday, November 2 -- Memorial Hall -- 2 p.m. Sep. 26 FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON (4) W, 3-0 Live Stats: dsuhornets.com Sep. 26 NORFOLK STATE (4) W, 3-1 Sep. 27 WAGNER (4) W, 3-0 Oct. 3 Hampton* W, 3-1 Hornets Host Busy Weekend After a big five-set conference win against Howard last Sunday, the Hornets return home Oct. 5 UMES* L, 0-3 Oct. 10 HOWARD* L, 2-3 to play three matches against Morgan State (10/31), Quinnipiac (11/1), and Coppin State (11/2). -

The Maryland State House Maryland State House Facts

The 20th & 21st Centuries The Maryland State House Maryland State House Facts As you cross into the newer, 20th century part of the Four Centuries of History ♦ Capitol of the United States, November 1783– State House, be sure to look up the grand staircase at August 1784 The Maryland State House was the first peacetime capitol the monumental painting of Washington Resigning His ♦ America’s first peacetime capitol of the United States and is the only state house ever to Commission by Edwin White, painted for the Maryland ♦ Oldest state house in America still in continuous Welcome have served as the nation’s capitol. Congress met in the General Assembly in 1858. legislative use to the Old Senate Chamber from November 26, 1783, to ♦ Declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960, the August 13, 1784. During that time, General George You will know you have left the 18th century part of the first state house in the nation to win such designation Maryland State House Washington came before Congress to resign his State House when you cross the black line in the floor. commission as commander-in-chief of the Continental Notice the fossils embedded in the black limestone. Once 18th Century Building Army and the Treaty of Paris was ratified, marking the A Self-Guided Tour for Visitors you cross that line, you are in the “new” section of the Date of construction: 1772–1779 official end of the Revolutionary War. In May 1784, building, built between 1902 – 1905, often called the Architect: Joseph Horatio Anderson Congress appointed Thomas Jefferson minister to France, “Annex.” It is in this section of the State House that the Builder: Charles Wallace the first diplomatic appointment by the new nation. -

Ashton Patriotic Sublime.5.Pdf (9.823Mb)

commercial spaces like theaters, and to performances spanning the gamut from the solemn, to the joyous. This diversity encompassed celebrations outside the expected calendar of national days. Patriotic sentiment was even a key feature of events celebrating the economic and commercial expansion of the new nation. The commemorative celebration for the laying of the foundation-stone of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the “great national work which is intended and calculated to cement more strongly the union of the Eastern and the Western States,” took place on July 4, 1828.1 It beautifully illustrated the musical ties that bound different spaces together – in this case a parade route, a temporary outdoor civic space, and the permanent space of the Holliday Street Theatre. Organizers chose July Fourth for the event, wishing to signal civic pride and affective patriotism. Baltimore filled with visitors in the days before the celebration, so that on the morning of the Fourth the “immense throng of spectators…filled every window in Baltimore-street, and the pavement below….fifty thousand spectators, at least, must have been present.” The parade was massive and incorporated a great diversity of groups, including “bands of music, trades, and other bodies.” One focal point was a huge model, “completely rigged,” of a naval vessel, the “Union,” complete with uniformed sailors. Bands playing patriotic tunes were interspersed amongst the nationalist imagery on display: militia uniforms, banners emblazoned with patriotic verse, national flags, eagle figures, shields, and more. Charles Carrollton, one of the last surviving signers of the Declaration of Independence, gave the main public address at the site, accompanied by a march composed for the occasion, the “Carrollton March” (see Figure 2.4). -

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties Within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia

Historic Context Study of Waterfowl Hunting Camps and Related Properties within Assateague Island National Seashore, Maryland and Virginia by Ralph E. Eshelman, Ph.D and Patricia A. Russell Eshelman & Associates July 21, 2004 For Assateague Island National Seashore National Park Service Department of Interior 7206 National Seashore Lane Berlin, Maryland 21811 i ii CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………………………………. ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………..iii INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………..1 Project background Clubs and lodges Definitions Regional context WATERFOWL HUNTING ON THE ATLANTIC ………………………………..7 Delaware North to New York Maryland Virginia North Carolina South to Georgia Assateague Island WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES……………………………..21 Land-Based Facilities Water-Based Facilities TYPICAL DAY AT A WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUB……………………….31 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC ASPECTS OF WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………………………………………………… 33 Owners Members Guests: The Rich and Famous Gender Guides Food Thrill of the Hunt Fraternal Comradeship Ethnicity of Support Staff Role in Conservation ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CAMPS AND LODGES…………………………………………………………………..47 ASSOCIATED PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF ASSATEGUE ISLAND WATERFOWL HUNTING CLUBS AND LODGES………….49 iii INVENTORY OF RESOURCES…………………………………………………52 Bob-O-Del Gun Club Bunting’s Gunning Lodge Clements’ Beach House Clements’ Boat House Green Run Lodge High Winds Gun Club Hungerford’s Musser’s Peoples & Lynch Pope’s Island Gun Club Valentine’s CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………72 REFERENCES CITED……………………………………………………………76 APPENDIX I ANNOTATED LIST OF GUN CLUBS AND LODGES IN MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA………………………………………90 APPENDIX II PROFESSIONAL TRAINING AND EXPERIENCE OF CONTEXT STUDY TEAM………………………………………………99 APPENDIX III CULTURAL LANDSCAPE FIELD SURVEY…………………………………100 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project benefited from numerous persons who assisted us in countless ways, shared knowledge, and otherwise made this study possible. -

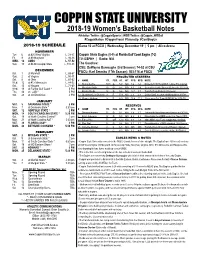

Coppin State University

COPPIN STATE UNIVERSITY 2018-19 Women’s Basketball Notes Athletics Twitter: @CoppinSports | WBB Twitter: @Coppin_WBBall #CoppinNation #CoppinProud #TalonsUp #CantStopUs 2018-19 SCHEDULE Game 10 at FGCU | Wednesday, December 19 | 5 pm | Alico Arena NOVEMBER Tue. 6 at #25 West Virginia L, 78-37 Coppin State Eagles (0-9) at Florida Gulf Coast Eagles (7-2) Fri. 9 at #9 Maryland L, 93-36 TV: ESPN+ | Radio: N/A WED. 14 UMBC L, 57-52 Sun. 18 at #6 Mississippi State L, 110-38 The Coaches: CSU: DeWayne Burroughs (3rd Season): 14-52 at CSU DECEMBER Sat. 1 at Marshall L, 88-67 FGCU: Karl Smesko (17th Season): 503-116 at FGCU Sun. 2 at Virginia L, 55-41 PROJECTED STARTERS Sat. 8 at Ohio L, 87-62 # NAME YR. POS. HT. WT. PPG RPG NOTE Wed. 12 at #13 Minnesota L, 84-52 0 Tsahai Corbie R-Fr. G 5-7 N/A 3.6 1.4 Named 2017 PSAL MVP, 3-time PSL Champ Sat. 15 at Niagara L, 71-69 Wed. 19 at Florida Gulf Coast ^ 5 PM 2 M a r a i y a h Smith So. G 5-5 N/A 6.3 2.4 Scored i n d o u b l e fi g u r e s 1 2 t i m e s i n 2 0 1 7 - 1 8 Thu. 20 vs. UAB ^ 5 PM 4 Brooke Fields Sr. G 5-6 N/A 12.1 2.7 Transfer from Roberts Wesleyan Sat. 29 at Old Dominion 4 PM 12 Oluwadamilola Oloyede Jr. -

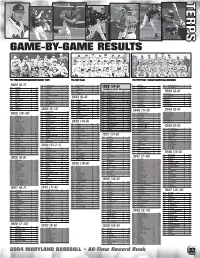

Game-By-Game Results

TERPS GAME-BY-GAME RESULTS The 1908 Maryland Agricultural College Team The 1925 Terps The 1936 Terps - Southern Conference Champions 1924 (5-7) 4-13 North Carolina L 9-12 5-1 Wake Forest W 8-7 4-15 Michigan L 0-6 5-8 Washington & Lee L 1-2 3-31 Vermont L 0-8 4-18 Richmond L 6-15 5-5 Duke L 4-7 1936 (14-6) 4-22 at Georgetown W 8-4 5-9 Georgetown L 1-9 4-9 Gallaudet W 13-1 4-30 NC State W 9-2 5-13 Richmond W 11-1 Southern Conf. Champions 4-25 Virginia Tech W 25-8 4-10 Marines W 8-1 5-3 Duke L 2-6 5-14 VMI W 9-5 3-26 Ohio State W 5-2 4-29 at Washington W 7-6 1943 (3-4) 4-17 Lehigh L 3-5 5-4 Virginia L 3-8 5-28 at Navy L 4-11 3-31 Cornell W 8-6 5-1 Duke W 9-8 at Fort Myers L 8-12 4-23 Georgia L 3-23 5-11 at Western Maryland W 4-2 4-1 Cornell L 6-7 5-3 William & Mary W 5-2 at Camp Holabird L 2-7 5-15 VMI L 5-6 4-24 Georgia L 8-9 1933 (6-4) 4-8 at Richmond L 0-2 5-5 Richmond W 8-5 Fort Belvoir W 18-16 5-16 at Navy W 7-4 4-25 West Virginia W 8-7 4-14 Penn State W 13-8 4-11 at VMI W 11-3 5-6 Washington W 5-2 at Navy JV W 13-4 5-1 NC State L 3-17 5-18 Washington & Lee W 6-5 4-17 at Duke L 0-8 4-18 Michigan W 14-13 5-16 Lafayette W 10-6 Fort Meade L 0-6 5-3 VMI L 7-11 5-18 Washington & Lee L 2-7 4-17 at Duke L 1-5 4-20 Richmond L 6-16 Greenbelt W 12-3 5-17 at Rutgers W 9-4 5-7 Washington W 7-1 5-19 at VMI W 2-1 4-18 at North Carolina L 0-8 4-23 Virginia L 3-4 at Fort Meade L 4-7 5-20 Georgetown W 4-0 5-14 Catholic W 8-0 4-19 Virginia L 6-11 4-25 at Georgetown L 2-5 5-20 at Virginia L 3-10 1929 (5-11) 5-9 at Washington & Lee W 4-0 4-28 West Virginia W 21-9 1944 (2-4) 4-3 Pennsylvania L 3-5 5-12 at VMI W 6-0 4-29 at Navy W 9-1 1940 (11-9) at Curtis Bay L 2-9 3-23 at North Carolina L 7-8 4-4 Cornell L 1-3 5-20 at Navy W 10-6 5-2 Georgetown W 12-9 Eng. -

PAPERS of the NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part Segregation and Discrimination, 15 Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series A: Legal Department Files UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier PAPERS OF THE NAACP Part 15. Segregation and Discrimination, Complaints and Responses, 1940-1955 Series A: Legal Department Files Edited by John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier Project Coordinator Randolph Boehm Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloglng-ln-Publlcatlon Data National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Papers of the NAACP. [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides. Contents: pt. 1. Meetings of the Board of Directors, records of annual conferences, major speeches, and special reports, 1909-1950 / editorial adviser, August Meier; edited by Mark Fox - pt. 2. Personal correspondence of selected NAACP officials, 1919-1939 / editorial - [etc.] - pt. 15. Segregation and discrimination, complaints and responses, 1940-1955. 1. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People-Archives. 2. Afro-Americans-Civil Rights-History-20th century-Sources. 3. Afro- Americans-History-1877-1964~Sources. 4. United States-Race relations-Sources. I. Meier, August, 1923- . II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Title. E185.61 [Microfilm] 973'.0496073 86-892185 ISBN 1-55655-460-5 (microfilm : pt. -

Free Health Screenings Available at Wellness Fair March 27–30

Free Health Screenings Available at Wellness Fair March 27–30 HE ANNUAL COUNTY EMPLOYEE WELLNESS FAIR is scheduled for March 27-30 at the Agri-Expo Center at 131 TEast Mountain Dr. The hours each day will be 6:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Employees will not be seen without an appointment, so be sure to schedule a time slot through your wellness representative. At the health fair, employees will be weighed and screened for high blood pressure, cholesterol and blood glucose. You will also submit their Personal Wellness Profiles. It is very important to complete the profile survey before you arrive for your appointment. Participation in this year’s fair is particularly important as it will establish a relationship between the employee and the county’s new employee Wellness Center, which will include a pharmacy, acute-care clinic and wellness program. Located in the E. Newton Smith Center on Fountainhead Lane, the Wellness Center is expected to open in early July. Once the center opens, all county employees will be able to use the Express Care Clinic and participate in the wellness programs offered through the wellness coordinator’s office. However, only employees and retirees who are enrolled in the county’s Blue Cross Blue Shield health insurance can use the pharmacy. All employees can participate in the four-day wellness fair. It is free and you will be on work time. Employees who are covered by the county’s Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance will save on their insurance premiums. MONTHLY RATES PER PAY PERIOD BASE RATES WITHOUT HEALTH RISK ASSESSMENT/BIOMETRICS Deputy Health Director Rod Jenkins reminds Employee Only $ 51.00 $ 25.50 employees to: Employee + Child $157.00 $ 78.50 • Schedule an appointment with their Employee + Children $254.00 $127.00 Employee + Spouse wellness representative.