Free Download, Last Accessed October 30, 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIAMI UNIVERSITY the Graduate School

MIAMI UNIVERSITY The Graduate School Certificate for Approving the Dissertation We hereby approve the Dissertation of Steven Almaraz Candidate for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ______________________________________ Director Kurt Hugenberg ______________________________________ Reader Allen McConnell ______________________________________ Reader Jonathan Kunstman ______________________________________ Graduate School Representative Monica Schneider ABSTRACT APPARENT SOCIOSEXUAL ORIENTATION: FACIAL CORRELATES AND CONSEQUENCES OF WOMEN’S UNRESTRICTED APPEARANCE by Steven M. Almaraz People make quick work of forming a variety of impressions of one another based on minimal information. Recent work has shown that people are able to make judgments of others’ Apparent Sociosexual Orientation (ASO) – an estimation of how interested another person is in uncommitted sexual activity – based on facial information alone. In the present work, I used three studies to expand the understanding of this poorly understood facial judgment by investigating the dimensionality of ASO (Study 1), the facial predictors of ASO (Study 2), and the consequences of these ASO judgments on men’s hostility and benevolence towards women (Study 3). In Study 1, I showed that men’s judgments of women’s Apparent Sociosexual Orientation were organized into judgments of women’s appearance of unrestricted attitudes and desires (Intrapersonal ASO) and their appearance of unrestricted behaviors (Behavioral ASO). Study 2 revealed that more attractive and more dominant appearing women were perceived as more sexually unrestricted. In Study 3, I found that women who appeared to engage in more unrestricted behavior were subjected to increased benevolent sexism, though this effect was primarily driven by unrestricted appearing women’s attractiveness. However, women who appeared to have sexually unrestricted attitudes and desires were subjected to increased hostility, even when controlling for the effects of the facial correlates found in Study 2. -

Tamarind 1990 - 2004

Tamarind 1990 - 2004 Author A. K. A. Dandjouma, C. Tchiegang, C. Kapseu and R. Ndjouenkeu Title Ricinodendron heudelotii (Bail.) Pierre ex Pax seeds treatments influence on the q Year 2004 Source title Rivista Italiana delle Sostanze Grasse Reference 81(5): 299-303 Abstract The effects of heating Ricinodendron heudelotii seeds on the quality of the oil extracted was studied. The seeds were preheated by dry and wet methods at three temperatures (50, 70 and 90 degrees C) for 10, 20, 30 and 60 minutes. The oil was extracted using the Soxhlet method with hexane. The results showed a significant change in oil acid value when heated at 90 degrees C for 60 minutes, with values of 2.76+or-0.18 for the dry method and 2.90+or-0.14 for the wet method. Heating at the same conditions yielded peroxide values of 10.70+or-0.03 for the dry method and 11.95+or-0.08 for the wet method. Author A. L. Khandare, U. Kumar P, R. G. Shanker, K. Venkaiah and N. Lakshmaiah Title Additional beneficial effect of tamarind ingestion over defluoridated water supply Year 2004 Source title Nutrition Reference 20(5): 433-436 Abstract Objective: We evaluated the effect of tamarind (Tamarindus indicus) on ingestion and whether it provides additional beneficial effects on mobilization of fluoride from the bone after children are provided defluoridated water. Methods: A randomized, diet control study was conducted in 30 subjects from a fluoride endemic area after significantly decreasing urinary fluoride excretion by supplying defluoridated water for 2 wk. -

Product Catalog

Product Catalog Bazaar Spices at Union Market 1309 5th Street NE Washington, DC 20002 202-379-2907 Bazaar Spices at Atlantic Plumbing 2130 8th Street NW Washington, DC 20001 202-379-2907 [email protected] | [email protected] www.bazaarspices.com www.facebook.com/bazaarspices | www.twitter.com/bazaarspices www.instagram.com/bazaarspices | www.pinterest.com/bazaarspices SPICY DC BLOG www.spicydc.com 1 Bazaar Spice|1309 5th Street NE, Washington, DC | 202-379-2907 | www.bazaarspices.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Who We Are We are Ivan and Monica, the owners of Bazaar Spices. We have lived in the District of Columbia for over 10 years. We left the Who We Are ....................................................................................... 2 corporate and nonprofit worlds to pursue our entrepreneurial dreams. Witnessing how local markets contribute to the fabric of a What We Do ....................................................................................... 3 community and how the spice and herb shop, alongside the butcher Why Bazaar Spices ............................................................................. 3 and the baker, forms the foundation of these markets; we were inspired to launch Bazaar Spices. What’s the Difference ........................................................................ 3 Product Categories ............................................................................. 4 Being fortunate to have had the opportunity to visit markets in the four corners of the world, we gained a deep understanding -

Method to Estimate Dry-Kiln Schedules and Species Groupings: Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods

United States Department of Agriculture Method to Estimate Forest Service Forest Dry-Kiln Schedules Products Laboratory Research and Species Groupings Paper FPL–RP–548 Tropical and Temperate Hardwoods William T. Simpson Abstract Contents Dry-kiln schedules have been developed for many wood Page species. However, one problem is that many, especially tropical species, have no recommended schedule. Another Introduction................................................................1 problem in drying tropical species is the lack of a way to Estimation of Kiln Schedules.........................................1 group them when it is impractical to fill a kiln with a single Background .............................................................1 species. This report investigates the possibility of estimating kiln schedules and grouping species for drying using basic Related Research...................................................1 specific gravity as the primary variable for prediction and grouping. In this study, kiln schedules were estimated by Current Kiln Schedules ..........................................1 establishing least squares relationships between schedule Method of Schedule Estimation...................................2 parameters and basic specific gravity. These relationships were then applied to estimate schedules for 3,237 species Estimation of Initial Conditions ..............................2 from Africa, Asia and Oceana, and Latin America. Nine drying groups were established, based on intervals of specific Estimation -

Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay)

BUSH BLITZ SPECIES DISCOVERY PROGRAM Brooklyn, Cloudland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) Nature Refuges Eubenangee Swamp, Hann Tableland, Melsonby (Gaarraay) National Parks Upper Bridge Creek Queensland 29 April–27 May · 26–27 July 2010 Australian Biological Resources Study What is Contents Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a four-year, What is Bush Blitz? 2 multi-million dollar Abbreviations 2 partnership between the Summary 3 Australian Government, Introduction 4 BHP Billiton and Earthwatch Reserves Overview 6 Australia to document plants Methods 11 and animals in selected properties across Australia’s Results 14 National Reserve System. Discussion 17 Appendix A: Species Lists 31 Fauna 32 This innovative partnership Vertebrates 32 harnesses the expertise of many Invertebrates 50 of Australia’s top scientists from Flora 62 museums, herbaria, universities, Appendix B: Threatened Species 107 and other institutions and Fauna 108 organisations across the country. Flora 111 Appendix C: Exotic and Pest Species 113 Fauna 114 Flora 115 Glossary 119 Abbreviations ANHAT Australian Natural Heritage Assessment Tool EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) NCA Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland) NRS National Reserve System 2 Bush Blitz survey report Summary A Bush Blitz survey was conducted in the Cape Exotic vertebrate pests were not a focus York Peninsula, Einasleigh Uplands and Wet of this Bush Blitz, however the Cane Toad Tropics bioregions of Queensland during April, (Rhinella marina) was recorded in both Cloudland May and July 2010. Results include 1,186 species Nature Refuge and Hann Tableland National added to those known across the reserves. Of Park. Only one exotic invertebrate species was these, 36 are putative species new to science, recorded, the Spiked Awlsnail (Allopeas clavulinus) including 24 species of true bug, 9 species of in Cloudland Nature Refuge. -

The Élan Vital of DIY Porn

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 11, No. 1 (March 2015) The Élan Vital of DIY Porn Shaka McGlotten In this essay, I borrow philosopher Henri Bergson’s concept élan vital, which is translated as vital force or vital impetus, to describe the generative potential evident in new Do-It- Yourself (DIY) pornographic artifacts and to resist the trend to view porn as dead or dead- ening. Bergson employed this idea to challenge the mechanistic view of matter held by the biological sciences of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, a view that considered the stuff of life to be reducible to brute or inert matter. Bergson argued, rather, that matter, insofar as it undergoes continuous change, is itself alive and not because of an immaterial, animat- ing principle, but because this liveliness is intrinsic to matter itself. I use Bergson’s élan vi- tal to think through the liveliness of gay DIY porn and for its contribution to a visual his- tory of desire, for the ways it changes the relationships between consumers and producers of pornography, and the ways it realizes new ways of stretching the pornographic imagination aesthetically and politically. It’s Alive I jump between sites. I watch a racially ambiguous young man with thick, muscular legs standing in front of a nondescript bathtub. He whispers, “I’m so horny right now,” rub- bing his cock beneath red Diesel boxer briefs. He turns and pulls his underwear down, arching his back to reveal a hairy butt. Turning to the camera again he shows off his modestly equipped, but very hard, dick. -

Plants for Tropical Subsistence Farms

SELECTING THE BEST PLANTS FOR THE TROPICAL SUBSISTENCE FARM By Dr. F. W. Martin. Published in parts, 1989 and 1994; Revised 1998 and 2007 by ECHO Staff Dedication: This document is dedicated to the memory of Scott Sherman who worked as ECHO's Assistant Director until his death in January 1996. He spent countless hours corresponding with hundreds of missionaries and national workers around the world, answering technical questions and helping them select new and useful plants to evaluate. Scott took special joy in this work because he Photo by ECHO Staff knew the God who had created these plants--to be a blessing to all the nations. WHAT’S INSIDE: TABLE OF CONTENTS HOW TO FIND THE BEST PLANTS… Plants for Feeding Animals Grasses DESCRIPTIONS OF USEFUL PLANTS Legumes Plants for Food Other Feed Plants Staple Food Crops Plants for Supplemental Human Needs Cereal and Non-Leguminous Grain Fibers Pulses (Leguminous Grains) Thatching/Weaving and Clothes Roots and Tubers Timber and Fuel Woods Vegetable Crops Plants for the Farm Itself Leguminous Vegetables Crops to Conserve or Improve the Soil Non-Leguminous Fruit Vegetables Nitrogen-Fixing Trees Leafy Vegetables Miners of Deep (in Soil) Minerals Miscellaneous Vegetables Manure Crops Fruits and Nut Crops Borders Against Erosion Basic Survival Fruits Mulch High Value Fruits Cover Crops Outstanding Nuts Crops to Modify the Climate Specialty Food Crops Windbreaks Sugar, Starch, and Oil Plants for Shade Beverages, Spices and Condiment Herbs Other Special-Purpose Plants Plants for Medicinal Purposes Living Fences Copyright © ECHO 2007. All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced for training purposes if Plants for Alley Cropping distributed free of charge or at cost and credit is given to ECHO. -

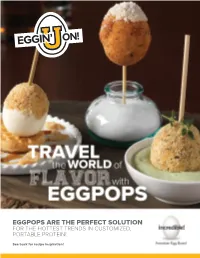

Eggpops Are the Perfect Solution for the Hottest Trends in Customized, Portable Protein!

EGGPOPS ARE THE PERFECT SOLUTION FOR THE HOTTEST TRENDS IN CUSTOMIZED, PORTABLE PROTEIN! See back for recipe inspiration! EGGPOPS ARE SIMPLE, FUN AND ATTENTION GRABBING — which makes them perfect for serving as an LTO item, as part of a PopUp concept or at special events. Sauce ‘em, dip ‘em, coat ‘em, pickle ‘em, dust ‘em! EggPops are an ideal canvas for exploring global flavors. MEDITERRANEAN/ GLOBAL LATIN AMERICAN/ NORTH ASIAN MIDDLE EAST/ CARIBBEAN AMERICA FOCUS NORTH AFRICAN Chili Lime Tandoori Spicy Orange Blossom Water Smoked BRINE/MARINADE/ Salsa Verde Ginger Mirin Piri Piri Dill Pickle Juice SMOKED - Submerge a Jalapeño Pineapple Miso Sauce Pepperoncini Juice Beet Juice shelled hard-boiled egg in Mojo Soy Dashi Green Olive Juice Buffalo Sauce brine or marinade for a few hours to infuse the flavors into the egg. Or trying smoking it for a unique flavor profile. (and/or) (and/or) (and/or) (and/or) Salsa Verde Crema Sriracha Aioli Tzatziki Maple Bacon Glaze Sofrito Aioli Sambal Crema Shakshuka Dip French Onion Dip Zesty Al Pastor Crema Gochujang Aioli Green Goddess Dressing Cajun Remoulade Chimichurri Sauce Thai Sweet Chili Sauce Sun-Dried Tomato Pesto Pimento Cheese Crema DIP - Create a dip/sauce Aji Amarillo Crema Szechuan Orange Sauce Harissa Yogurt Blue Cheese Dip base for the shelled Pinapple Jerk Glaze Korean BBQ Sauce Romesco Aioli South Carolina Mustard BBQ hard-boiled eggpop to Guajillo Pepper Confit Kaya Coconut Cream Balsamic Aioli Blackened Cajun Aioli rest in. (and/or) (and/or) (and/or) (and/or) Elotes Flavored Powder -

LOQ 1A: Lipid Oxidation Fundamentals Chairs: Fereidoon

ABSTRACTS 2018 AOCS ANNUAL MEETING AND EXPO May 6–9, 2018 LOQ 1a: Lipid Oxidation Fundamentals Chairs: Fereidoon Shahidi, Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada; and Weerasinghe Indrasena, DSM Nutritional Products, Canada Role of Antioxidants and Stability of Frying Oils Atherosclerosis-associated-death is still on the S.P.J. Namal Senanayake*, Camlin Fine Sciences, rise and expected to more than double by 2030. USA The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is The role of antioxidants in delaying lipid multifaceted and includes oxidative stress, oxidation of edible oils and fats is well known. endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance, and a Synthetic antioxidants are often added to edible large number of inflammatory and immunologic oils and fats to retard oxidation during storage factors. Traditional risk factors for the and frying; however, consumer reaction on development of cardiovascular disease synthetic antioxidants remains undesirable. complications include smoking, dyslipidemia, Consequently, there is an increasing interest in hypertension, and diabetes. Therapies mostly the search for naturally-derived antioxidants for associated with cholesterol synthesis inhibition frying applications. The analysis of the different have been developed and directed at these methodologies for frying oils include the traditional risk factors with major clinical peroxide value, anisidine value, free fatty acid benefits. Yet, a high residual risk of content, Oil Stability Index (OSI), viscosity, and cardiovascular disease development still remains. residual antioxidant levels, among others. In this Dietary modification and physical activity afford presentation, the chemistry of frying as well as modest amount of cholesterol lowering. The role action and fate of antioxidants during frying of inflammation and the immune system will be discussed. -

550Ccc5465f35683157a0f091d3

1 2 SUMMARY 4K p.05 CURRENT AFFAIRS & INVESTIGATION p.09 INVESTIGATION & SPORT p.13 FOOD INDUSTRY p.15 SCIENCE & KNOWLEDGE p.19 ARCHAEOLOGY & HISTORY p.27 SOCIAL ISSUES & HUMAN INTEREST p.37 WILDLIFE p.42 NATURE & ENVIRONMENT p.47 TRAVEL & DISCOVERY p.57 DOCU DRAMA & EDUCATIONAL p.69 DOCU SOAP p.71 LIFESTYLE p.73 FILLERS & AERIAL VIEW p.76 PEOPLE & PLACES: AROUND THE SEA p.81 3 4 5 Ultra HD programs LENGTH: MY EVERYDAY PANIC 90’ DIRECTOR: Planète en danger Sameh Estefanos How and to what extent Egypt & other developing countries have PRODUCER: been affected by Climate changes, since it was transformed to be Shot by Shot fact as the population of the weak areas in north of Egyptian Delta COPYRIGHT: are suffering by the rapid raising of Mediterranean sea level, a farm- 2021 ers lost their agricultural land and fishermen were forced to stop LANGUAGE sailing in addition to those who are planning for illegal immigration VERSION AVAILABLE: which makes global fear! English Watch the video UPCOMING JUNE 2021 LOOKING FOR INTERNATIONAL PRESALES LENGTH: 52’ XIANJU, THE WAY OF BALANCE DIRECTOR: Xianju, la voie de l’équilibre Patrice Desenne 200 miles south of Shanghai lies the Xianju National Park. PRODUCER: It is a pocket of great plant and animal biodiversity that also Grand Angle Productions holds a treasure of ancestral culture and artisanal and ag- COPYRIGHT: ricultural traditions. It shows a now rare image of China. 2020 How can it be protected and developed without disfiguring it? LANGUAGE Some strategies are emerging with the help of international partners. -

Brand Listing for the State of Texas

BRAND LISTING FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS © 2016 Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits SOUTHERNGLAZERS.COM Bourbon/Whiskey A.H. Hirsch Carpenders Hibiki Michter’s South House Alberta Rye Moonshine Hirsch Nikka Stillhouse American Born Champion Imperial Blend Old Crow Sunnybrook Moonshine Corner Creek Ironroot Republic Old Fitzgerald Sweet Carolina Angel’s Envy Dant Bourbon Moonshine Old Grand Dad Ten High Bakers Bourbon Defiant Jacob’s Ghost Old Grand Dad Bond Tom Moore Balcones Devil’s Cut by Jim James Henderson Old Parr TW Samuels Basil Haydens Beam James Oliver Old Potrero TX Whiskey Bellows Bourbon Dickel Jefferson’s Old Taylor Very Old Barton Bellows Club E.H. Taylor Jim Beam Olde Bourbon West Cork Bernheim Elijah Craig JR Ewing Ole Smoky Moonshine Westland American Blood Oath Bourbon Evan Williams JTS Brown Parker’s Heritage Westward Straight Blue Lacy Everclear Kavalan Paul Jones WhistlePig Bone Bourbon Ezra Brooks Kentucky Beau Phillips Hot Stuff Whyte & Mackay Bonnie Rose Fighting Cock Kentucky Choice Pikesville Witherspoons Bookers Fitch’s Goat Kentucky Deluxe Private Cellar Woodstock Booze Box Four Roses Kentucky Tavern Rebel Reserve Woody Creek Rye Bourbon Deluxe Georgia Moon Kessler Rebel Yell Yamazaki Bowman Hakushu Knob Creek Red River Bourbon Bulleit Bourbon Hatfield & McCoy Larceny Red Stag by Jim Beam Burnside Bourbon Heaven Hill Bourbon Lock Stock & Barrel Redemption Rye Cabin Fever Henderson Maker’s Mark Ridgemont 1792 Cabin Still Henry McKenna Mattingly & Moore Royal Bourbon Calvert Extra Herman Marshall Mellow Seagram’s 7 -

Determinants of Production and Market Supply of Korarima (Aframomum Corrorima (Braun) Jansen)) in Kaffa Zone, Southern Ethiopia

www.kosmospublishers.com [email protected] Research Article Advances in Agriculture, Horticulture and Entomology AAHE-115 ISSN 2690 -1900 Determinants of production and market supply of Korarima (Aframomum Corrorima (Braun) Jansen)) in Kaffa zone, Southern Ethiopia Ejigu Mulatu1*, Andualem Gadisa2 1Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Bonga Research Center Socio economics research division: Bonga, Ethiopia 2Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Bonga Agricultural Research Center: Crop research division Bonga, Ethiopia Received Date: April 03, 2020; Accepted Date: April 14, 2020; Published Date: April 24, 2020 *Corresponding author: Ejigu Mulatu, Southern Agricultural Research Institute, Bonga Research Center Socio economics research division: Bonga, Ethiopia. Tel: +251910140961; Email: [email protected] Abstract Korarima in a Kaffa zone could be explained as the most popular spice as it’s widely production and prolonged socio-economic importance. Relevant information on production and marketing of korarima is needed for improving productivity and design of effective policy. This study was conducted with specific objectives: to assess status of korarima production, to identify factors affecting market supply of korarima and to identify constraints in production and marketing of korarima in Kaffa zone, Southern Ethiopia. The study was based on the data collected from 116sample households selected through multistage sampling technique. Descriptive statistics and econometric model were used to analyze the data. A multiple linear regression model was employed to assess the factors affecting of households’ market supply of korarima output. Major constraints in production and marketing of korarima in the zone includes disease, animal and pest damage, low yield due to climate change effect, low productivity of existing varieties, poor extension support, lack of improved korarima production practices, lack of well-designed output marketing center, and traditional harvesting and post-harvest handling techniques.