CHAPTER I EARLIER RESEARCH by Michael Hare and Richard Bryant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Herefordshire. Aconbury

DIRECTORY.] HEREFORDSHIRE. ACONBURY. 13 ABBEYDORE, or Dore, is a pa.rish and village, in the Powell Rev. Thomas Prosser M.A., D.T.. Dorstone Rectory, Golden Valley and OD the river Dore, celebrated for its Hereford trout, and from which the parish derives its name, with a Rees Capt. Richard Powell, The Firs, Abergavenny station on the Golden Valley railway, which forms a junction Robinson Edwd. Lewis Gavin esq. D.L. Poston,Peterchurch at Pontrilas station on the Newport, Abergavenny, and Here Trafford Henry Randolph esq. D.L. Michaelchurch court, ford railway, 2l miles north-west, 13 south-west from Here Hereford ford, 14 west from Ross, alld is the head of a union, in the Trafford Edwd.Guy esq. D.L. Michaelchurchcourt,Hereford Southern division of the county, Webtree hundred, Hereford Clerk to the Magistrates, Thomas Llanwarne, Hereford county court district, rural deaneryof Weobley (firstdivision) 1tnd archdeaconry and diocese of Hereford. Thechurchof St. Petty Sessions are held at the Police Station on alternate Mary is a large building of stone, in the Transition, Norman mondays at II a.m. and Early English styles, and formerly belonged to the The places within the petty sessional division are :-Abbey Cistercian abbey founded here in 1147, by Robert Ewias, dore, Bacton, Crasswall Dulas, Ewvas Harold, Kender Lord of Ewias Harold : of the conventual church, the choir, church, Kentchurcb, Kilpeck, Kingstone, LlanciIlo, presbytery, transept and eastern chapel-aisle remain as well Llanveynoe, Longtown, Madley, Micbaelchurch Escley, as the group-chapels, north and south, the latter restored Newton, Peterchurch, Rowlstone, St. Devereux, St. Mar in 1894 by Miss Hoskyns, the only surviving daughter of garet's, Thruxton, Tyberton, Treville, Turn3stone, Vow ChandosWren Hoskyns esq. -

UNIT 4, FIELD BARN FARM, FIELD BARN LANE, CROPTHORNE , WR10 3LY Rent

UNITUNIT 4,4, FIELDFIELD BARNBARN FARM,FARM, FIELDFIELD BARNBARN LANE,LANE, CROPTHORNE CROPTHORNE, , WR10WR10 3LY3LY Industrial warehouse with office space TO LET extending to 114.95sq m (1237sq ft) ground floor with an additional 93.3sq m (1004sq ft) of mezzanine floor area on site car parking and staff facilities Rent: £6,500 Per annum 1-3 MERSTOW GREEN • EVESHAM • WORCS • WR11 4BD COMMERCIAL TEL: 01386 765700 EMAIL : [email protected] Website address: www.timothylea-griffiths.co.uk UNIT 4, FIELD BARN FARM, FIELD BARN LANE, CROPTHORNE , WR10 3LY TENURE IMPORTANT NOTES LOCATION The unit is available on a new lease with an Services, fixtures, equipment, buildings and land. None of these have been tested by Timothy Lea & Griffiths. An interested Units 3 and 4 Field Barn Farm are located anticipated term of between 3-5 years party will need to satisfy themselves as to the type, condition and within the village of Cropthorne, approximately suitability for a purpose. 4.5 miles distant from Pershore Town Centre BUSINESS RATES Value Added Tax, VAT may be payable on the purchase price and approximately 3.5 miles distant from the This unit is to be re-assessed and/or the rent and/or any other charges or payments detailed market town of Evesham. Cropthorne is an above. All figures quoted exclusive of VAT. Intending attractive rural village situated off the main LOCAL AUTHORITY purchasers and lessees must satisfy themselves as to the B4084 road linking Evesham to Pershore. The Wychavon District Council applicable VAT position, if necessary, by taking appropriate professional advice. -

14 May 2020 338.9 KB

LONGTOWN GROUP PARISH COUNCIL Craswall, Llanveynoe, Longtown and Walterstone DATE OF PUBLICATION: Wednesday 13th May 2020 TO: ALL MEMBERS OF LONGTOWN GROUP PARISH COUNCIL: Councillors Cecil (Chair), Hardy (Vice-Chair), Hope, Palmer, Powell, Probert, Tribe, G Watkins and L Watkins. (Five Vacancies) NOTICE OF MEETING You are hereby summoned to attend the remote Parish Council Meeting of the Longtown Group Parish Council to be held on Wednesday 20th May at 8.00pm via Zoom. Please click this link to join or follow the link at the end of the agenda. Paul Russell Clerk to the Council [email protected] AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST 3. ADOPT MINUTES OF PREVIOUS MEETING – To approve the minutes of the meeting held on 19th February 2020. Copy attached. 4. OPEN FORUM – For local residents to raise local matters. 5. POLICE – To receive a report from the Police, if available. 6. WARD COUNCILLOR – To receive a report from the Ward Councillor, if available. 7. PLANNING APPLICATIONS NUMBER SITE DESCRIPTION 200839 White Haywood Farm, Craswall, Replacement of flush fitting timber casement Hereford, Herefordshire, HR2 0PH window to utility room. 8. GRANTS, REFUSALS & APPEALS NUMBER SITE DESCRIPTION DECISION 200529 Llandraw Farm, Proposed nonmaterial Approved Craswall HR2 0PW amendment to planning permission 192932 (Proposed extension to existing farmhouse). To allow extension to be built 600mm higher. 194134 Land lying south of Proposed non-material Refused High House, amendment to planning Llanveynoe, permission ref 190786; (Erection Longtown of stables - siting of three stables and one field shelter; for horses and one storage container for water) - re-arranged; 1 | P a g e design/position of stables and water storage butts x 2 201005 Land East of Great Prior notification of a polytunnel to Prior approval refused Trewern, Longtown, provide improved growing Hereford, HR2 0LW conditions for horticultural produce. -

The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Pershore Worcestershire WR10 3LE Guide Price £325,000

14 Broad Street, Pershore, Worcestershire WR10 1AY Telephone: 01386 555368 [email protected] The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Pershore Worcestershire WR10 3LE For Sale by Private Treaty Guide Price £325,000 A THREE BEDROOM INTERESTING PERIOD DWELLING BEING PART OF A DIVIDED FARMHOUSE OFFERING CHARACTER ACCOMMODATION WITH EXPOSED TIMBERS, WOOD BURNING STOVES AND FARMHOUSE KITCHEN Entrance Hallway, Cloakroom, Sitting Room, Dining Room, Kitchen/ Breakfast Room, Utility Room, Bedroom 1 with En Suite, 2 further Bedrooms, Bathroom, Courtyard Parking, Garage, Garden, Oil C.H The Chapter House Top Street Charlton Situation The Chapter House is a period property with origins dating back some 200 years. This property once part of a large farmhouse is now divided into two dwellings with character features, exposed timbers and open fireplaces with wood burning stoves inset. The moulded covings are particularly attractive especially in the sitting room. The accommodation is set on different levels giving further character to this interesting property. Charlton is a popular residential village with a sample of both period and modern properties, a village green and a local public house. There is an active church. The surrounding countryside is predominantly farming with orchards, arable and market gardening land. Charlton is approximately two miles from Evesham, four miles from Pershore and has the popular villages of Cropthorne and Fladbury which are separated by the Jubilee bridge over the river Avon. The historic town of Evesham lies to the south east of Charlton bordered by the river Avon and the new bridge giving access to this old market town. There are supermarkets and high street shopping, doctors’ surgeries, veterinary surgeries, modern cinema and other excellent facilities in this area. -

Annual Report 2013

ANNUAL REPORT Report for the year ended 31 August 2013 WHAT IS THE METHODIST COLLECTION? The Methodist Modern Art Collection comprises paintings, limited edition prints and reliefs. In the early 1960s John Morel Gibbs, a Methodist layman and art collector – realising that many Non-conformists had little appreciation of the insights that contemporary artists could bring to the Christian story – decided to create a collection of prime examples of such work that could be toured around the country. This he did, with the help of Methodist minister, the Revd Douglas Wollen. The works they acquired became the core of the present Collection – described as “the best denominational collection of modern art outside the Vatican”. The Collection includes leading names from the British art world of the last 100 years, such as Edward Burra, Elisabeth Frink, Eric Gill, Patrick Heron and Graham Sutherland. In recent years the Collection has acquired works by artists from the world church, including Jyoti Sahi from India, Sadao Watanabe from Japan and John Muafangejo from Namibia. Still expanding, works by artists such as Craigie Aitchison, Peter Howson, Susie Hamilton, Clive Hicks-Jenkins and Maggi Hambling have been acquired, and today it comprises 50 paintings, prints, drawings, relief and mosaic works. The Collection is valued as a key resource for mission and evangelism, whether on a denominational or an ecumenical basis. The Collection, in whole or in part, is available as a touring exhibition, and has travelled widely, to town and city galleries, cathedrals, churches and schools, showing at four to six venues a year. When not on tour, the Collection is stored under the care of a custodian at the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History, Oxford Brookes University. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

Coronavirus Resources for Social Prescribing Wychavon

Coronavirus resources for social prescribing Wychavon Social prescribers will be supporting communities through this pandemic by maintaining phone contact with vulnerable clients and promoting local initiatives. One of them being the ‘Here to Help’ website at: http://www.worcestershire.gov.uk/here2help For the latest on information and local response: https://www.wychavon.gov.uk There are five ways you can help your community: ñ Take care of yourself and stay healthy – wash your hands and follow advice on self- isolation or social distancing ñ Call, chat and check – swap phone numbers with your immediate neighbours, check on neighbours and loved ones - particularly if they are vulnerable - help provide them with food and other essentials, alert relevant organisations if you are concerned about their welfare ñ Be kind and think of others – Don’t bulk buy. There are plenty of supplies for everyone if people just buy what they need. Use local community information groups on social media to share information, offer surplus supplies of essentials to those in need and avoid wasting food. ñ Get online to stay in touch – use your phone, video calling and social media to stay in touch with people, especially if you are self isolating ñ Share accurate advice and information – do not speculate or scaremonger. It only heightens people’s anxiety. Use reputable news sources as a source of information, the Government website or the NHS website. ñ For more help and advice visit the Here 2 Help website. Elderly or Vulnerable and needing assistance: ● Get coronavirus support as an extremely vulnerable person to register for additional support with daily living tasks such as shopping and social care ● To be contacted by a volunteer fill in the Here 2 Help form on the Worcestershire County Council website: RequestForHelp ● Ring Community Action on 01684 892381 and leave a message with a phone number and what the need is, or email [email protected] and someone will be in touch. -

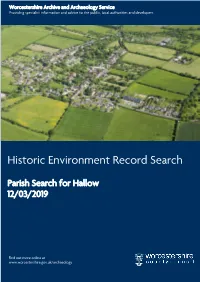

Historic Environment Record Search

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service Providing Villagespecialist hall information and advice to the public, local authorities and developers Historic Environment Record Search Parish Search for Hallow 12/03/2019 Find out more online at www.worcestershire.gov.uk/archaeology 0 Historic Environment Record Search Author: Webley, A Version 2 Date of Issue: 12/06/2019 Contents: An Archaeological Summary for your search area Archaeological Summary, Statutory and other Designations Information about the data sent to you Introduction, Guidelines for Access, Copyright, Planning Policy, The HER Data Glossary and Terms Glossary of Commonly used terms, General periods in the HER Modern and Historic Mapping 1841 Tithe Map of the Parish of Hallow. Digitised Extract. 1841 Tithe Map of the Parish of Hallow over Modern OS. Ordnance Survey, © Crown Copyright. 1887 1st Edition OS Map 1:10560 (2 maps) over Modern OS Map. Ordnance Survey, © Crown Copyright. 1903-04 2nd Edition OS Map 1:2500 (2 maps) Ordnance Survey, © Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing HER features: Prehistoric and Roman Period © Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing HER features: Medieval Period © Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing HER features: Post Medieval Period (2 Maps) © Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing HER features: 20th Century© Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing Historic Buildings of Worcestershire Project Points© Crown Copyright. Modern OS map showing HER features: Historic Landscape Character © Crown Copyright. The HER short report Monuments Lists sorted by period follow directly after each HER Features Map A Full Monument list sorted by monument type and Scheduled Ancient Monuments List (if present), follow after the map section. -

Herefordshire News Sheet

CONTENTS ARS OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE FOR 1991 .................................................................... 2 PROGRAMME SEPTEMBER 1991 TO FEBRUARY 1992 ................................................... 3 EDITORIAL ........................................................................................................................... 3 MISCELLANY ....................................................................................................................... 4 BOOK REVIEW .................................................................................................................... 5 WORKERS EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION AND THE LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETIES OF HEREFORDSHIRE ............................................................................................................... 6 ANNUAL GARDEN PARTY .................................................................................................. 6 INDUSTRIAL ARCHAEOLOGY MEETING, 15TH MAY, 1991 ................................................ 7 A FIELD SURVEY IN KIMBOLTON ...................................................................................... 7 FIND OF A QUERNSTONE AT CRASWALL ...................................................................... 10 BOLSTONE PARISH CHURCH .......................................................................................... 11 REDUNDANT CHURCHES IN THE DIOCESE OF HEREFORD ........................................ 13 THE MILLS OF LEDBURY ................................................................................................. -

Heritage at Risk Register 2013

HERITAGE AT RISK 2013 / WEST MIDLANDS Contents HERITAGE AT RISK III Worcestershire 64 Bromsgrove 64 Malvern Hills 66 THE REGISTER VII Worcester 67 Content and criteria VII Wychavon 68 Criteria for inclusion on the Register VIII Wyre Forest 71 Reducing the risks X Publications and guidance XIII Key to the entries XV Entries on the Register by local planning authority XVII Herefordshire, County of (UA) 1 Shropshire (UA) 13 Staffordshire 27 Cannock Chase 27 East Staffordshire 27 Lichfield 29 NewcastleunderLyme 30 Peak District (NP) 31 South Staffordshire 32 Stafford 33 Staffordshire Moorlands 35 Tamworth 36 StokeonTrent, City of (UA) 37 Telford and Wrekin (UA) 40 Warwickshire 41 North Warwickshire 41 Nuneaton and Bedworth 43 Rugby 44 StratfordonAvon 46 Warwick 50 West Midlands 52 Birmingham 52 Coventry 57 Dudley 59 Sandwell 61 Walsall 62 Wolverhampton, City of 64 II Heritage at Risk is our campaign to save listed buildings and important historic sites, places and landmarks from neglect or decay. At its heart is the Heritage at Risk Register, an online database containing details of each site known to be at risk. It is analysed and updated annually and this leaflet summarises the results. Heritage at Risk teams are now in each of our nine local offices, delivering national expertise locally. The good news is that we are on target to save 25% (1,137) of the sites that were on the Register in 2010 by 2015. From St Barnabus Church in Birmingham to the Guillotine Lock on the Stratford Canal, this success is down to good partnerships with owners, developers, the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF), Natural England, councils and local groups. -

THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES of ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, Including Their Descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD

Rowlestone and Kentchurch Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study THE SKYDMORES/ SCUDAMORES OF ROWLESTONE, HEREFORDSHIRE, including their descendants at KENTCHURCH, LLANCILLO, MAGOR & EWYAS HAROLD. edited by Linda Moffatt 2016© from the original work of Warren Skidmore CITATION Please respect the author's contribution and state where you found this information if you quote it. Suggested citation The Skydmores/ Scudamores of Rowlestone, Herefordshire, including their Descendants at Kentchurch, Llancillo, Magor & Ewyas Harold, ed. Linda Moffatt 2016, at the website of the Skidmore/ Scudamore One-Name Study www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com'. DATES • Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. • Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

Worcestershire Has Fluctuated in Size Over the Centuries

HUMAN GENETICS IN WORCESTERSHIRE AND THE SHAKESPEARE COUNTRY I. MORGAN WATKIN County Health Department, Abet ystwyth Received7.x.66 1.INTRODUCTION THEwestern limits of Worcestershire lie about thirty miles to the east of Offa's Dyke—the traditional boundary between England and Wales —yet Evesham in the south-eastern part of the county is described by its abbot in a petition to Thomas Cromwell in as situated within the Principality of Wales. The Star Chamber Proceedings (No. 4) in the reign of Henry VII refer to the bridge of stone at Worcester by which the king's subjects crossed from England into Wales and the demonstrations against the Act of 1430 regulating navigation along the Severn were supported by large numbers of Welshmen living on the right bank of the river in Worcestershire. The object of the investigation is to ascertain whether significant genetic differences exist in the population of Worcestershire and south-western Warwickshire and, in particular, whether the people living west of the Severn are more akin to the Welsh than to the English. The possibility of determining, on genetic grounds, whether the Anglo- Saxon penetration was strongest from the south up the rivers Severn and Avon, or across the watershed from the Trent in the north, or from the east through Oxfordshire and Warwickshire is also explored. 2. THECOUNTY Worcestershirehas fluctuated in size over the centuries and Stratford-on-Avon came for a period under its jurisdiction while Shipston-on-Stour, now a Warwickshire township, remained in one of the detached portions of Worcestershire until the turn of the present century.