Holding De Beers Accountable for Trading Conflict Diamonds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

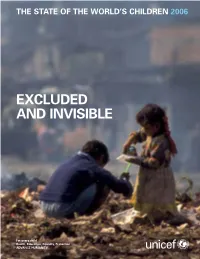

Excluded and Invisible

THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 EXCLUDED AND INVISIBLE THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2006 © The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), 2005 The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Permission to reproduce any part of this publication The State of the World’s Children 2006 is required. Please contact the Editorial and Publications Section, Division of Communication, UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, UNICEF NY (3 UN Plaza, NY, NY 10017) USA, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: 212-326-7434 or 7286, Fax: 212-303-7985, E-mail: [email protected]. Permission E-mail: [email protected] will be freely granted to educational or non-profit Website: www.unicef.org organizations. Others will be requested to pay a small fee. Cover photo: © UNICEF/HQ94-1393/Shehzad Noorani ISBN-13: 978-92-806-3916-2 ISBN-10: 92-806-3916-1 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the advice and contributions of many inside and outside of UNICEF who provided helpful comments and made other contributions. Significant contributions were received from the following UNICEF field offices: Albania, Armenia, Bolivia, Botswana, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Guinea-Bissau, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Madagascar, Malaysia, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nigeria, Occupied Palestinian Territory, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Peru, Republic of Moldova, Serbia and Montenegro, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Venezuela and Viet Nam. Input was also received from Programme Division, Division of Policy and Planning and Division of Communication at Headquarters, UNICEF regional offices, the Innocenti Research Centre, the UK National Committee and the US Fund for UNICEF. -

Sierra Leone

SIERRA LEONE 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 15, No. 1 (A) – January 2003 I was captured together with my husband, my three young children and other civilians as we were fleeing from the RUF when they entered Jaiweii. Two rebels asked to have sex with me but when I refused, they beat me with the butt of their guns. My legs were bruised and I lost my three front teeth. Then the two rebels raped me in front of my children and other civilians. Many other women were raped in public places. I also heard of a woman from Kalu village near Jaiweii being raped only one week after having given birth. The RUF stayed in Jaiweii village for four months and I was raped by three other wicked rebels throughout this A woman receives psychological and medical treatment in a clinic to assist rape period. victims in Freetown. In January 1999, she was gang-raped by seven revels in her village in northern Sierra Leone. After raping her, the rebels tied her down and placed burning charcoal on her body. (c) 1999 Corinne Dufka/Human Rights -Testimony to Human Rights Watch Watch “WE’LL KILL YOU IF YOU CRY” SEXUAL VIOLENCE IN THE SIERRA LEONE CONFLICT 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] January 2003 Vol. -

NEWSLETTER Wetstraat 200, Rue De La Loi Brussel B-1049 Bruxelles Tel.: (32-2) 295 76 20 Fax: (32-2) 295 54 37

EC Editors: Address: World Wide Web: ISSN COMPETITION Bernhard Friess European Commission, http://europa.eu.int/comm/ 1025-2266 POLICY Nicola Pesaresi J-70, 00/123 competition/index_en.html NEWSLETTER Wetstraat 200, rue de la Loi Brussel B-1049 Bruxelles Tel.: (32-2) 295 76 20 Fax: (32-2) 295 54 37 competition policy 2001 Number 3 October NEWSLETTER Published three times a year by the Competition Directorate-General of the European Commission Also available online: http://europa.eu.int/comm/competition/publications/cpn/ Inside: La politique européenne de la concurrence dans les services postaux hors monopole General Electric/Honeywell — An insight into the Commission's investigation and decision B2B e-marketplaces and EC competition law: where do we stand? Ports italiens: Les meilleures histoires ont une fin BASF/Pantochim/Eurodiol: Change of direction in European merger control? Adoption by the Commission of a Methodology for analysing State aid linked to stranded costs European Competition Day in Stockholm, 11 June 2001 Main developments on: Antitrust — Merger control — State aid control Contents Articles 1 La politique européenne de la concurrence dans les services postaux hors monopole, par Jean-François PONS et Tilman LUEDER 5 General Electric/Honeywell — An Insight into the Commission's Investigation and Decision, by Dimitri GIOTAKOS, Laurent PETIT, Gaelle GARNIER and Peter DE LUYCK 14 B2B e-marketplaces and EC competition law: where do we stand?, by Joachim LÜCKING Opinions and comments 17 Ports italiens: Les meilleures histoires -

Global Rough Diamond Production Since 1870

GLOBAL ROUGH DIAMOND PRODUCTION SINCE 1870 A. J. A. (Bram) Janse Data for global annual rough diamond production (both carat weight and value) from 1870 to 2005 were compiled and analyzed. Production statistics over this period are given for 27 dia- mond-producing countries, 24 major diamond mines, and eight advanced projects. Historically, global production has seen numerous rises—as new mines were opened—and falls—as wars, political upheavals, and financial crises interfered with mining or drove down demand. Production from Africa (first South Africa, later joined by South-West Africa [Namibia], then West Africa and the Congo) was dominant until the middle of the 20th century. Not until the 1960s did production from non-African sources (first the Soviet Union, then Australia, and now Canada) become impor- tant. Distinctions between carat weight and value affect relative importance to a significant degree. The total global production from antiquity to 2005 is estimated to be 4.5 billion carats valued at US$300 billion, with an average value per carat of $67. For the 1870–2005 period, South Africa ranks first in value and fourth in carat weight, mainly due to its long history of production. Botswana ranks second in value and fifth in carat weight, although its history dates only from 1970. Global production for 2001–2005 is approximately 840 million carats with a total value of $55 billion, for an average value per carat of $65. For this period, USSR/Russia ranks first in weight and second in value, but Botswana is first in value and third in weight, just behind Australia. -

Profile of Internal Displacement : Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 15 October, 2003) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 799 07 00 Fax: + 41 22 799 07 01 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 9 BACKGROUND TO THE CONFLICT 9 CHRONOLOGY OF SIGNIFICANT EVENTS SINCE INDEPENDENCE (1961 - 2000) 9 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 13 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 16 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 18 RELATIVELY STABLE SECURITY SITUATION SINCE SIGNING OF CEASE-FIRE AGREEMENT IN ABUJA ON 10 NOVEMBER 2000 20 CIVIL WAR DECLARED OVER FOLLOWING THE FULL DEPLOYMENT OF UNAMSIL AND THE COMPLETION OF DISARMAMENT (JANUARY 2002) 22 REGIONAL EFFORTS TO MAINTAIN PEACE IN SIERRA LEONE (2002) 23 SIERRA LEONEANS GO TO THE POLLS TO RE-ELECT AHMAD TEJAN KABBAH AS PRESIDENT (MAY 2002) 24 SIERRA LEONE’S SPECIAL COURT AND TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION START WORK (2002-2003) 25 MAIN CAUSES OF DISPLACEMENT 28 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT -

Sierra Leone and Conflict Diamonds: Establshing a Legal Diamond Trade and Ending Rebel Control Over the Country's Diamond Resources

SIERRA LEONE AND CONFLICT DIAMONDS: ESTABLSHING A LEGAL DIAMOND TRADE AND ENDING REBEL CONTROL OVER THE COUNTRY'S DIAMOND RESOURCES "Controlof resourceshas greaterweight than uniform administrativecontrol over one's entire comer of the world, especially in places such as Sierra Leone where valuable resources are concentratedand portable.' I. INTRODUCTION Sierra Leone2 is in the midst of a civil war that began in 1991, when the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) invaded the country from neighboring Liberia.3 RUF rebels immediately sought control over one of the country's richest resources--diamonds.4 Since gaining control over the most productive diamond fields, the rebels have at their fingertips an endless supply of wealth with which to fund their insurgencies against the Government of Sierra Leone.' The RUF rebels illicitly trade diamonds for arms in open smuggling operations. 6 Diamonds sold by the RUF, in order to fund the rebel group's military action in opposition to Sierra Leone's legitimate and internationally recognized government, are called "conflict diamonds."7 1. WIulIAM RENO, WARLORD POLITICS AND AFRICAN STATES 140 (1998). 2. Sierra Leone is located on the west coast of Africa north of Liberia and south of Guinea. The country has 4,900,000 residents, almost all of whom belong to one of 13 native African tribes. Country: Sierra Leone, Sept. 3,2000, availableat LEXIS, Kaleidoscope File. One of the primary economic activities in Sierra Leone is mining of its large diamond deposits that are a major source of hard currency. Countries that predominantly import goods from Sierra Leone include Belgium, the United States, and India. -

De Beers and Beyond: the History of the International Diamond Cartel∗

De Beers and Beyond: The History of the International Diamond Cartel∗ Diamonds are forever hold of them. The idea of making diamonds available to the general public seemed un- A gemstone is the ultimate luxury thinkable. When diamonds were first found product. It has no material use. Men in South Africa in 1867, however, supply in- and women desire to have diamonds creased rapidly, although the notion of dia- not for what they [diamonds] can do monds as a precious and rare commodity re- but for what they desire.1 mained to the present day. Similar to the gold miners in California, dia- To hear these words from a person who at- mond miners in South Africa tended to rush to tributes his entire wealth and power to the the latest findings.2 As a matter of principle, trade of diamonds illustrates the peculiar na- diamond miners preferred to work by them- ture of the diamond market: Jewelry dia- selves. However, the scarcity of resourceful monds are unjustifiably expensive, given they land and the need for a minimum of common are not actually scarce and would fetch a price infrastructure forced them to live together in of $2 to $30 if put to industrial use. Still, limited areas. In order to fight off latecom- by appealing to the customers’ sentiment, di- ers and to settle disputes, Diggers Committees amonds are one of the most precious lux- were formed and gave out claims in a region. ury items and enjoy almost global acceptance. Each digger would be allocated one claim, or, This fact is often attributed to the history at most, two. -

Child Soldiers and Blood Diamonds OVERVIEW & OBJECTIVES GRADES

Civil War in Sierra Leone: Child Soldiers and Blood Diamonds OVERVIEW & OBJECTIVES GRADES This lesson addresses the civil war in Sierra Leone to 8 illustrate the problem of child soldiers and the use of diamonds to finance the war. Students will draw TIME conclusions about the impact of the ten years civil war on the people of Sierra Leone, as well as on a boy who 4-5 class periods lived through it, by reading an excerpt from his book, A Long Way Gone. This lesson explores the concepts REQUIRED MATERIALS of civil war, conflict diamonds, and child soldiers in Sierra Leone while investigating countries of West Computer with projector Africa. Students will also examine the Rights of the Child and identify universal rights and Computer Internet access for students responsibilities. Pictures of child soldiers Poster paper and markers Students will be able to... Articles: Chapter One from A Long Way describe the effects of Sierra Leone’s civil war. Gone by Ishmael Beah; “What are Conflict analyze the connection between conflict Diamonds”; “How the Diamond Trade diamonds and child soldiers. Works”; “Rights for Every Child” analyze the role diamonds play in Africa’s civil wars Handouts: “Pre-Test on Sierra Leone”; compare their life in the United States with the “Post-Test on Sierra Leone”; “Sierra Leone lives of people in Sierra Leone. and Its Neighbors” describe the location and physical and human geography of Sierra Leone and West Africa. identify factors that affect Sierra Leone’s economic development analyze statistics to compare Sierra Leone and its neighbors. assess the Rights of the Child for Sierra Leone analyze the Rights of the Child and the responsibility to maintain the rights MINNESOTA SOCIAL STUDIES STANDARDS & BENCHMARKS Standard 1. -

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

Millions of Civilians Have Been Killed in the Flames of War... But

VOLUME 2 • NUMBER 131 • 2003 “Millions of civilians have been killed in the flames of war... But there is hope too… in places like Sierra Leone, Angola and in the Horn of Africa.” —High Commissioner RUUD LUBBERS at a CrossroadsAfrica N°131 - 2003 Editor: Ray Wilkinson French editor: Mounira Skandrani Contributors: Millicent Mutuli, Astrid Van Genderen Stort, Delphine Marie, Peter Kessler, Panos Moumtzis Editorial assistant: UNHCR/M. CAVINATO/DP/BDI•2003 2 EDITORIAL Virginia Zekrya Africa is at another Africa slips deeper into misery as the world Photo department: crossroads. There is Suzy Hopper, plenty of good news as focuses on Iraq. Anne Kellner 12 hundreds of thousands of Design: persons returned to Sierra Vincent Winter Associés Leone, Angola, Burundi 4 AFRICAN IMAGES Production: (pictured) and the Horn of Françoise Jaccoud Africa. But wars continued in A pictorial on the African continent. Photo engraving: Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Aloha Scan - Geneva other areas, making it a very Distribution: mixed picture for the 12 COVER STORY John O’Connor, Frédéric Tissot continent. In an era of short wars and limited casualties, Maps: events in Africa are almost incomprehensible. UNHCR Mapping Unit By Ray Wilkinson Historical documents UNHCR archives Africa at a glance A brief look at the continent. Refugees is published by the Media Relations and Public Information Service of the United Nations High Map Commissioner for Refugees. The 17 opinions expressed by contributors Refugee and internally displaced are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do UNHCR/P. KESSLER/DP/IRQ•2003 populations. not imply the expression of any With the war in Iraq Military opinion or recognition on the part of officially over, UNHCR concerning the legal status UNHCR has turned its Refugee camps are centers for of a territory or of its authorities. -

G U I N E a Liberia Sierra Leone

The boundaries and names shown and the designations Mamou used on this map do not imply official endorsement or er acceptance by the United Nations. Nig K o L le n o G UINEA t l e a SIERRA Kindia LEONEFaranah Médina Dula Falaba Tabili ba o s a g Dubréka K n ie c o r M Musaia Gberia a c S Fotombu Coyah Bafodia t a e r G Kabala Banian Konta Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu Bendugu Forécariah li Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Se Bagbe r Madina e Bambaya g Jct. i ies NORTHERN N arc Sc Kurubonla e Karina tl it Mateboi Alikalia L Yombiro Kambia M Pendembu Bumbuna Batkanu a Bendugu b Rokupr o l e Binkolo M Mange Gbinti e Kortimaw Is. Kayima l Mambolo Makeni i Bendou Bodou Port Loko Magburaka Tefeya Yomadu Lunsar Koidu-Sefadu li Masingbi Koundou e a Lungi Pepel S n Int'l Airport or a Matotoka Yengema R el p ok m Freetown a Njaiama Ferry Masiaka Mile 91 P Njaiama- Wellington a Yele Sewafe Tongo Gandorhun o Hastings Yonibana Tungie M Koindu WESTERN Songo Bradford EAS T E R N AREA Waterloo Mongeri York Rotifunk Falla Bomi Kailahun Buedu a i Panguma Moyamba a Taiama Manowa Giehun Bauya T Boajibu Njala Dambara Pendembu Yawri Bendu Banana Is. Bay Mano Lago Bo Segbwema Daru Shenge Sembehun SOUTHE R N Gerihun Plantain Is. Sieromco Mokanje Kenema Tikonko Bumpe a Blama Gbangbatok Sew Tokpombu ro Kpetewoma o Sh Koribundu M erb Nitti ro River a o i Turtle Is. o M h Sumbuya a Sherbro I. -

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners

UNICEF Photo of the Year – Previous Award Winners 2014 First Prize Insa Hagemann / Stefan Finger, Germany, laif Their reportage on the effects of sextourism in the Philippines gives an insight in the situation of children whose fathers live abroad. Second Prize Christian Werner, Germany, laif For his reportage on internally displaced people from Shinghai district, Iraq Third Prize Brent Stirton, South Africa, Getty Images for his reportage “Before and after eye surgery” on children with congenital cataract blindness in India. 2013 Winner Niclas Hammarström, Sweden, Kontinent His photo reportage captures the life of the children in Aleppo caught between the frontlines. 2012 First Prize Alessio Romenzi, Italien, Agentur Corbis Images The winning picture shows a girl waiting for medical examination at a hospital in Aleppo, Syria. The camera captures the fear in her eyes as she looks at a man holding a Kalashnikov. Second Prize Abhijit Nandi, India, Freelance Photographer In a long-term photo project, the photographer documents the many different forms of child labor in his home country. Third Prize Andrea Gjestvang, Norwegen, Agentur Moment The third prize was awarded to Norwegian photographer Andrea Gjestvang for her work with the victims of the shooting on Utøya Island. Forth Prize Laerke Posselt, Dänemark, Agentur Moment for her look behind the scenes of beauty pageants for toddlers in the USA. 1 2011 First Prize Kai Löffelbein, Germany, Student, University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hannover for his photo of a boy at the infamous toxic waste dump Agbogbloshie, near Ghana’s capital Accra. Surrounded by highly toxic fumes and electronic waste from Western countries, the boy is lifting the remnants of a monitor above his head.