Orı́ and Neuroscience: a Contextualization of the Yoruba Idea of Causality in the Age of Modern Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

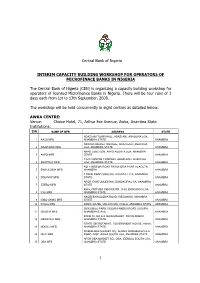

Interim Capacity Building for Operators of Microfinance Banks

Central Bank of Nigeria INTERIM CAPACITY BUILDING WORKSHOP FOR OPERATORS OF MICROFINACE BANKS IN NIGERIA The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is organizing a capacity building workshop for operators of licensed Microfinance Banks in Nigeria. There will be four runs of 3 days each from 1st to 13th September, 2008. The workshop will be held concurrently in eight centres as detailed below: AWKA CENTRE: Venue: Choice Hotel, 71, Arthur Eze Avenue, Awka, Anambra State. Institutions: S/N NAME OF MFB ADDRESS STATE ADAZI ANI TOWN HALL, ADAZI ANI, ANAOCHA LGA, 1 AACB MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NKWOR MARKET SQUARE, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 2 ADAZI-ENU MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA AKPO JUNCTION, AKPO AGUATA LGA, ANAMBRA 3 AKPO MFB STATE ANAMBRA CIVIC CENTRE COMPLEX, ADAZI-ENU, ANAOCHA 4 BESTWAY MFB LGA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NO 1 MISSION ROAD EKWULOBIA P.M.B.24 AGUTA, 5 EKWULOBIA MFB ANAMBRA ANAMBRA 1 BANK ROAD UMUCHU, AGUATA L.G.A, ANAMBRA 6 EQUINOX MFB STATE ANAMBRA AFOR IGWE UMUDIOKA, DUNUKOFIA LGA, ANAMBRA 7 EZEBO MFB STATE ANAMBRA KM 6, ONITHSA OKIGWE RD., ICHI, EKWUSIGO LGA, 8 ICHI MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NNOBI/EKWULOBIA ROAD, IGBOUKWU, ANAMBRA 9 IGBO-UKWU MFB STATE ANAMBRA 10 IHIALA MFB BANK HOUSE, ORLU ROAD, IHIALA, ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA EKWUSIGO PARK, ISUOFIA-NNEWI ROAD, ISUOFIA, 11 ISUOFIA MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA ZONE 16, NO.6-9, MAIN MARKET, NKWO-NNEWI, 12 MBAWULU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA STATE SECRETARIAT, GOVERNMENT HOUSE, AWKA, 13 NDIOLU MFB ANAMBRA STATE ANAMBRA NGENE-OKA MARKET SQ., ALONG AMAWBIA/AGULU 14 NICE MFB ROAD, NISE, AWKA SOUTH -

2Nd September, 1982 Vol. 69

tte | No.44 Lagos - 2nd September, 1982 Vol. 69 CONTENTS . 3 Page . Page Movements ofOrficers oe ee 882-90 BabanlaPostal Agency—Openingof .. -. 896 Trade Dispute between the National Union Ibido Street, Ageg¢Postal Agency—Opening of and Non-Metallic Products of .. ool ee ee -- 897 Workers and Management of Metal Box NdiogwuaméechiPostalAgency—Opening of 897 Toyo Glass Limited oe o. -- 891 Akata-Ogbomosho Postal Agency— TradeDispute between the National Union Openingof ..: .. - o- 2. 897 ofPaperandPa rProducts Workers and Ungwar Shanu Postal Agency—Opening of .. 897 "Managementof WahumPackages Nigeria Housing Estate, Kaduna Postal Agency— Limited ..) ww 8. Openngof = ws wesw 897 Permitto Operate Non-Scheduled Passenger Nzerem Postal Agéncy—Opening of -- 897 and CargoAirCharterServices 1... .. 892 Ukubie Postal Agency—Opening of .. -- 898 Asa-Umunka Postal Agency— Introduction Zambuk Postal Agency: ing of -- “898 of Savings Bank Facilities ., oe -- 892 Enugu-Agidi Post Office—Opening of ' 398 Eha-AlumonaPostalAgency—Openingof ,, 892 Afor-Agulu Postal Agency—-Openingof .. 898 Ojobiofia Postal Agency—Introduction of ° Salami Street, Mafoluku, Mushin Postal = SavingsBank Facilities .. 892 Agency—Opening of _—.. oe -. 898 Kumo Post Offi ingof .., 892 . Darazo Post Office-Opening of cee ‘898 - | Ikot-Ekpenyong Postal Agency—Opening Ikot Okoro Sub-Post Office—Opening of 899 of .. oe oe . oe +» 893 IsuofiaPostal Agen¢y—Introductionof Uwene-Ekpoma Postal Agency—Openingof 893 Savings Bank Facilities .. .. .,. 899 Igbakwu Postal Agency—Opening of .. 893 . Agbogugu Sub-Post Office—Openingof 899 AwgbuPostal Agency—Introduction of ‘Tungbo Postal Agency-—Opening of -- §899 Savings Bank Facilities . , .. -- 893 Kachia Road, Kaduna Postal Agency— Enem Postal Agency—Opening of .. “»» $93 Opening of .. o- - ee -- 899 ' Asata-Enugu Sub-Post Office—Openingof ., 893 Alaropo Akinwole Postal Agency—Opening TbalaPostal Agency— Opening of ,, . -

List of Community Banks Converted to Microfinance Banks As at 31St

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA IMPORTANT NOTICE LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS THAT HAVE SUCESSFULLY CONVERTED TO MICROFINANCE BANKS AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2007 Following the expiration of December 31, 2007 deadline for all existing community banks to re-capitalize to a minimum of N20 million shareholders’ fund, unimpaired by losses, and consequently convert to microfinance banks (MFB), it is imperative to publish the outcome of the conversion exercise for the guidance of the general public. Accordingly, the attached list represents 607 erstwhile community banks that have successfully converted to microfinance banks with either final licence or provisional approval. This list does not, however, include new investors that have been granted Final Licences or Approvals-In- Principle to operate as microfinance banks since the launch of Microfinance Policy on December 15, 2005. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) hereby states categorically that only the community banks on this list that have successfully converted to microfinance banks shall continue to be supervised by the CBN. Members of the public are hereby advised not to transact business with any community bank which is not on the list of these successfully converted microfinance banks. Any member of the public, who transacts business with any community bank that failed to convert to MFB does so at his/her own risk. Members of the public are also to note that the operating licences of community banks that failed to re-capitalize and consequently do not appear on this list, have automatically been revoked pursuant to Section 12 of BOFIA, 1991 (as amended). For the avoidance of the doubt, new applications either as a Unit or State Microfinance Banks from potential investors or promoters shall continue to be received and processed for licensing by the Central Bank of Nigeria. -

2011 Phd Diss Final

Supervisor and First Examiner: Prof. Dr. Alexander Bergs Second Examiner: Prof. Dr. Thomas Hoffmann Date of defence: May 25, 2011 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Truth be told: When I left Lagos for Germany in September 2003 the plan was for me to spend just two weeks in Osnabrück attending the Computational Linguistics Fall School but Providence intervened and changed the plan in remarkable ways. I can only connect the dots now looking back. Particularly, Prof. Peter Bosch was God-sent as he encouraged and gave me the moral support to apply for the Master's degree in the International Cognitive Science Programme, Osnabrück which I did and never regretted the choice. It is the same Peter Bosch who introduced me to my “Doktorvater” (my PhD supervisor), Prof. Alexander Bergs, for my eventual doctoral work. Alex Bergs' warm welcome in 2007 was amazing and since then he has ensured that Osnabrück is truly an academic home for me. The Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (DAAD), the German Academic Exchange Service, supported my doctoral study with grants and scholarship and I am grateful for these. I appreciate the efforts of the following friends and scholars who assisted with the administration and co-ordination of the questionnaire in Nigeria: Prof. Charles Esimone, Dr. Tunde Opeibi, Dr. Peter Elias, Dr. Rotimi Taiwo, Mr. Stephen Folaranmi and Dr. Olufemi Akinola. I am also thankful for the assistance of Dr. Kolawole Ogundari, Mr. Michael Osei and Mr. Emmanuel Balogun with the coding of the completed questionnaire. The Deeper Christian Life Ministry (DCLM) family and leadership in Niedersachsen and Bremen provided me with the right social and spiritual atmosphere for a successful completion of my postgraduate studies in Osnabrück and I am ever thankful for the fellowship and kindness of the DCLM family. -

Bank Directory Page 1 S/N Name Staff Staff Position Address Website 1

Bank Directory S/N Name Staff Staff Position Address Website 1 Central Bank Of Nigeria Mr. Godwin Emefiele, Governor Central Business District, Garki, www.cbn.gov.ng HCIB Abuja 2 Nigeria Deposit Insurance Alhaji Umaru Ibrahim, MNI, Managing Plot 447/448, Constitution http://ndic.org.ng/ Corporation FCIB Director/Chief Avenue, Central Business Executive District, Garki, Abuja 3 Access Bank PLC Mr. Herbert Wigwe, FCA Group Managing 1665, Oyin Jolayemi Street, www.accessbankplc.com Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 4 Diamond Bank PLC Mr. Uzoma Dozie, FCIB Group Managing Plot 1261 Adeola Hopewell www.diamondbank.com Director/Chief Street, Victoria Island, Lagos, Executive Lagos , 5 Ecobank Nigeria PLC Mr. Patrick Akinwuntan Group Managing Plot 21, Ahmadu Bello Way, www.ecobank.com Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 6 First City Monument Bank PLC Mr. Adam Nuru Managing Primrose Towers, 6-10 www.fcmb.com Director/Chief Floors ,17A, Tinubu Square, Executive Officer Lagos 7 Fidelity Bank PLC Nnamdi J. Okonkwo Managing 2, Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria www.fidelitybankplc.com Director/Chief Island, Lagos Executive 8 First Bank Of Nigeria Limited Dr. Adesola Kazeem Group Managing 35, Marina, Lagos www.firstbanknigeria.com Adeduntan, FCA Director/Chief Executive Officer 9 Guaranty Trust Bank PLC (GT Bank) Mr. Olusegun Agbaje, Managing Plot 1669, Oyin Jolayemi Street, www.gtbplc.com HCIB Director/Chief Victoria Island, Lagos Executive 10 Citibank Nigeria Limited Mr. Akin Dawodu MD/CEO Charles S. Sankey House,27 www.citigroup.com Kofo Abayomi Street, Victoria Island, Lagos 11 Keystone Bank LTD Mr. Hafiz Olalade Bakare Managing 1, Keystone Bank Crescent, www.keystonebankng.com Director/Chief Victoria Island Executive Page 1 Bank Directory 12 Polaris Bank PLC Mr. -

PDF Download

Journal of Tourism Management Research 2021 Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 57-67. ISSN(e): 2313-4178 ISSN(p): 2408-9117 DOI: 10.18488/journal.31.2021.81.57.67 © 2021 Conscientia Beam. All Rights Reserved. DEVELOPING CLUSTER FOR MOUNTAINS AND HILLS TOURISM IN EKITI STATE, SOUTHWEST, NIGERIA 1 Agbebi, P.A.1+ Department of Hospitality, Leisure and Tourism, Moshood Abiola Ogunjinmi, A.A.2 Polytechnic, Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Oyeleke, O.O.3 2,3,4 4 Department of Ecotourism and Wildlife Management, School of Adetola, B.O. Agriculture and Agricultural Technology, Federal University of Technology, (+ Corresponding author) Akure Ondo State, Nigeria. ABSTRACT Article History The study described the development of cluster for mountains and hills tourism Received: 12 January 2021 potentials in Ekiti State. Mapping and direct observation were used to collect both Revised: 15 February 2021 Accepted: 2 March 2021 primary and secondary data. Mapping was done by the use of Geographic Information Published: 18 March 2021 Sysytem (GIS), and Remote Sensing Tools (RST) which properly identified the GPS corodinates and photographs of mountains and hills locations in Ekiti State. These were Keywords later downloaded using Arc GIS software for further analysis and the production of Mapping Observation multiple maps such as elevation, slope map, shaded relief map and contour map of Ekiti Geographic information system State. Findings clealy showed 57 elevations which were 600m and above, and 245 Remote sensing control communities elevations that were less than 600m in different proportions and heights spread across Visitors. 27 communities in the 3 zones of Ekiti State. Thus, communities that have two or more mountains and hills at different locations formed cluster as tourism destinations with proposed headquaters where all administrative works will be controlled. -

POVERTY and WELFARE in COLONIAL NIGERIA, 1900-1954 By

POVERTY AND WELFARE IN COLONIAL NIGERIA, 1900-1954 by UYILAWA USUANLELE A thesis submitted to the Department of History in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada September 2010 Copyright © Uyilawa Usuanlele, 2010 ABSTRACT This study examines the interface of poverty and development of state welfare initiatives colonial Nigeria. It attempts to unravel the transformation and the nature and character of poverty afflicting majority of Nigerians since the period immediately preceding colonialism and under colonial rule. It looks at the causes and manifestations of poverty as well as the nature of social welfare in pre-colonial Nigerian societies in relation to the new forms of poverty that British Colonial policies visited on the society. Poverty in the colonial period is shown to have been caused by changes in power relations and accompanying administrative and economic reorganization of the society which facilitated the diversion of labour, resources and surplus produce from family and household use to the colonial state, firms and their agents. This new form of poverty was manifested in the loss of family and household self-sufficiency and the inability to meet personal survival needs and obligations, making the majority unable to participate fully in the affairs of their communities. This dissertation looks at how the British Colonial State tried to achieve its objective of exploitation and deal with the problem of poverty in its various manifestations using indigenous institutions and practices and other non- indigenous strategies in the face of growing African resistance and declining productivity. It argues that over-aching strategy of development represented by the Colonial Development and Welfare Act of 1940 and subsequent amendments and community development were designed to co-opt the emergent civil society into acquiescence with the social system and contain further resistance, and as such could not provide welfare nor alleviate the problem of poverty. -

List of Community Banks Before Conversion to Microfinance Bank

OTHER FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS DEPARTMENT LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS BEFORE CONVERSION TO MICROFINACE BANKS AS AT 31ST DECEMBER, 2007 S/N OLD NAME ADDRESS STATE ABIA STATE 1 ABIA STATE UNIVERSITY CB UTURU, ISUIKWUATO LGA, ABIA STATE ABIA AMAIKPE SQUARE, AFOR AROCHUKWU MARKET, AROCHUKWU, ABIA 2 AROCHUKWU CB STATE. ABIA 3 CHIBUEZE CB 82, EHI ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 4 OBIA CB 135, ABA-OWERRI ROAD,ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 5 OLD UMUAHIA CB ABA ROAD, OPP. AFOR UBEJI MARKET, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 6 OKEMINI CB NO 125, MARKET ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 7 EKEOHA CB 120, CLIFORD STREET, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 8 NKPA CB AMAOHORO NKPA, BENDE LGA, ABIA STATE ABIA 9 OBIOMA CB 148, JUBILEE ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 10 OHAFIA CB 87, AROCHUKWU ROAD, AMAEKPU, OHAFIA, ABIA STATE ABIA OHAMBELE CB UKWA EAST LGA, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 11 12 UMUCHUKWU CB 6 BENDE ROAD, UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE ABIA 13 UZUAKOLI CB 37, MARKET ROAD, UZUAKOLI, ABIA STATE ABIA 14 NSULU CB 26, FACTORY ROAD, ABA, ABIA STATE ABIA 15 IHECHIOWA CB CIVIC CENTRE, UMUYE, IHECHIOMA, AROCHUKWU LGA, ABIA STATE ABIA 16 EBEM-OHAFIA CB 247, EMI NJOKU ROAD, EBEM OHA, ABIA STATE ABIA 17 ABRIBA CB ERINMA HALL SECRETARIAT, ABRIBA, ABIA STATE ABIA ABUJA FCT 18 ACE CB 3 DANIEL ALIYU STREET, KWALI, F.C.T., ABUJA ABUJA 19 ALLIANCE CB 16, SAMUEL LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVORD, GARKI, ABUJA ABUJA 20 ANCHORAGE CB HIGHBURY PLAZA, 104 GADO NASKO RD. KUBWA, ABUJA ABUJA 21 NCWS CB PLOT 559C , AREA 11, GARKI, ABUJA ABUJA 22 GWAGWALADA CB 36 ECWA ROAD, GWAGWALADA, ABUJA ABUJA 23 GWARIMPA CB GWARIMPA, ABUJA ABUJA 24 MUNICIPAL CB 8, SAMBRERIO CRESCENT, F.H.A. -

Studies on Small Hydro-Power Potentials of Itapaji Dam in Ekiti State, Nigeria

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 5 Issue 1|| January 2016 || PP.28-36 Studies on Small Hydro-Power Potentials of Itapaji Dam in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Olumuyiwa Oludare FAGBOHUN Department of Electrical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti,Nigeria Abstract: Lack of constant electricity supply with the use of convectional mode are major causes of poverty in many rural areas in Nigeria. An overview of small hydro power potentials in Nigeria to mitigate against the problem of constant electricity supply in rural areas is discussed with surveyed states and expected total generation. A study on the potentials of Itapaji dam in Ekiti state, Nigeria for small hydro power generation is presented. The maximum annual discharge of the dam was calculated as 23.24 cubic metre/sec, with an average nominal flow discharge of 8.33cubic metre/sec, and an average minimal flow of 1.78 cubic metre/sec, while the estimated hydro power potential of the dam is about 1.30MW, being generated with an average annual mean discharge of 8.33m3/sec with a reservoir capacity balance of 1.922 x 109m3/year. The components required for small hydro power scheme was discussed for familiarization as well as an assessment of the environmental impact for overall viability. Electricity generation from this hydro scheme can easily be extended to surrounding communities along the present gridline without any major engineering effort, as well as a reduction in green-house gas emission in terms of avoided fossil fuels backed generating schemes. -

Communities Needs for the Proposed 2021 Budget

EKITI STATE NIGERIA COMMUNITIES NEEDS FOR THE PROPOSED 2021 BUDGET 1 A. EKITI SOUTH SENATORIAL DISTRICT IKERE LOCAL GOVERNMENT 1. Construction of Ajolagun Bridge 2. Rehabilitation of Township Road 3. Construction of Ikere-Ilawe Ekiti road 4. Re-contruction of Ikere-Ijare road 5. Construction of Ikere-Igbara-Odo road 6. Construction of Farmstead roads 7. Rehabilitation of Health Care Centre 8. Provision of Tap/Potable Water 9. Provision of Electric Transformers 10. Renovation of Schools 11. Renovation of Courts of Justice 12. Provision of Public Toilets 13. Provision of Standard Stadium 14. Provision of Public and Digital Library 15. Construction of Recreational Centres for the Youth 16. Renovation of Oba’s Palace 17. Construction of Standard Motor Parks 1 ISE/ORUN LOCAL GOVERNMENT (a) ISE EKITI 1. Rehabilitation of Ikere/Ise/Emure road 2. Rehabilitation of Ijan/Ise road 3. Agbado/Ise/Uso road (H.E you promise to do it since 2013/2014) 4. Construction of Permanent Trailer Parks 5. Construction of Modern Motor Park At Ise-Ekiti 6. Provision of Public Toilet(Public School, Motor Parks, Markets, Etc) 7. Preservation afforestation of Ise Reserve Area 8. Modern Resettlement Market (Sasa) for Hausa Community 9. Rehabilitation of Arinjale Palace 10. Erosion and Flood Control at Omi Akomoa and Omi Omo 11. Completion and Rehabilitation of Community roads e.g. Ireke- Oke Odi road, Omiye road, Secretariat etc 12. Repair and Construction of functioning Pipes Borehole Water 13. Completion of Central Hall 14. Grading of rural roads and rural electrification (b) ORUN EKITI 15. Making Ekiti State School of Midwifery Operational 1 16. -

A Historical Analysis of the Interconnectivity of Ogun Onire

DOI 10.32370/IA_2019_01_5 A Historical Analysis of the Interconnectivity of Ogun Onire Festival and Ire-Ekiti: Tracing the Ancestral Link Adeleye, Oluwafunke Adeola Department of History and International Studies Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti. 08067172929 [email protected] Abstract Ogun is a prominent god in Yoruba traditional religious belief. He is renowned and might not require the introduction needed for some other deities in Yorubaland. This study examines the migration account of the origin of the people of Ire-Ekiti, belief about Supreme Being (God) who is worshipped through gods in Yorubaland prior to the coming of the Europeans and the indigenous culture in Ire-Ekiti before the advent of Western Culture. The study focuses principally on the form of Ogun that does not enjoy prominence, which represent a deviation from its other forms in Yorubaland. The focus of this study is to assess the heroic deeds of Ogun, the deity on the evolution of Ire community in Ekiti State. The study examines the circumstances culminating in the emergence of the celebration of Ogun, a deity in Yorubaland. Though Ogun is peculiar to the Yoruba race, he will be discussed majorly within the boundaries of Ire-Ekiti. The study makes use of historical analysis to achieve its objectives. To attain this, primary and secondary sources were used. Primary sources include interview, praise poems, cognomen and rituals. The secondary sources include written materials e.g. journals, textbooks, newspapers, monographs and internet materials. Keywords: Festival, Ogun, Ire Ekiti, Yoruba deities, Culture Introduction Festivals are celebrated to preserve the cultural heritage of the society. -

Toyin Falola

Christianity and Social Change in Africa Essays in Honor of J.D.Y. Peel Christianity and Social Change in Africa Essays in Honor of J.D.Y. Peel edited by Toyin Falola Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Copyright © 2005 Toy in Falola All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Christianity and social change in Africa : essays in honor of J.D.Y. Peel / edited by Toyin Falola. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-59460-135-6 1. Church and social problems—Nigeria. 2. Church and social prob- lems—Africa, West. 3. Social change—Nigeria. 4. Social change—Africa, West. 5. Nigeria—Social conditions—1960– 6. Africa, West—Social condi- tions—1960– I. Peel, J. D. Y. (John David Yeadon), 1941– II. Falola, Toy in. III. Title. HN39.N55C48 2005 306.6'76608—dc22 2005007640 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent St. Durham, NC 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America Contents List of Figures Contributors Part A Context and Personality Chapter 1 Introduction 3 Toyin Falola Chapter 2 John Peel 27 T.C. McCaskie Part B Yoruba World Chapter 3 The Cultural Work of Yoruba Globalization 41 Stephan Palmié Chapter 4 Confusion and Empiricism: Several Connected Thoughts 83 Jane I. Guyer Chapter 5 Between the Yoruba and the Deep Blue Sea: The Gradual Integration of Ewe Fishermen on the Lagos-Badagry Seabeach 99 Axel Klein Chapter 6 “In the Olden Days”: Histories of Misbehaving Women in Ado-Odo, Southwestern Nigeria 117 Andrea Cornwall Chapter 7 “Let your garments always be white...” Expressions of Past and Present in Yoruba Religious Textiles 139 Elisha P.