Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

UN MÓN DIVERS Guia Intercultural NOVA EDICIÓ AMPLIADA

UN MÓN DIVERS Guia intercultural NOVA EDICIÓ AMPLIADA PROJECTE Servei de Llengües i Terminologia de la Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya COORDINACIÓ DE LA GUIA Jordi Pujol REDACCIÓ Guillem Vidal GRAFISME Esteva&Estêvão Aquest nova edició ha rebut el suport de la Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Barcelona, desembre de 2019 ÍNDEX PRESENTACIÓ.............................5 TRANSPORT Sobre dues rodes . 18 COMUNICAR-SE Taxis aquàtics . 18 El cos no enganya........................6 Carnet de conduir .......................19 Begudes i sobretaula .....................6 La llei de la carretera . 19 Parlar poc o parlar massa . 7 Tarifes i bitllets combinats................19 Presentar-se . 7 Les xarxes de metro . 20 Espai personal . 7 Noves formes de transport urbà ...........20 Noms i cognoms .........................8 Taxis ..................................20 Les targetes de visita . 8 Reverències.............................8 ESTUDIS Sous d’estudiant . 21 FORMALS O INFORMALS? Any sabàtic . 21 Tu o vostè . 9 Mestre o professor ......................22 Els imperatius ...........................9 Tràmits burocràtics......................22 Small talks.............................10 Sistemes d’avaluació ....................22 Gestos i significats ......................10 Fer campana . 23 Mostres d’afecte en públic . 10 «Coffee breaks» com a espai de relació social . 23 Preguntar l’edat ........................ 11 Nous exàmens . .23 Salutacions informals.................... 11 Contacte ocular......................... 11 VIDA UNIVERSITÀRIA Vestimenta a classe . 24 RELACIONS PERSONALS Vigila amb les olors! . 24 La importància de la família . 12 Les cerimònies de graduació . 25 Anticonceptius . 12 Un màster... amb la família? . 25 Lligar a l’estranger . 13 Resar en temps lectius...................25 Amics per sempre? ......................13 El preu d’estudiar .......................26 Dir que no . 13 Homes, dones i atenció al públic . -

Look Book — Holiday 2012 Ince 1976, Peruvian Connection Has Based Its Artisan-Made,S Luxury Fiber Collections on Ethnographic Textiles from Around the World

Look Book — Holiday 2012 ince 1976, Peruvian Connection has based its Sartisan-made, luxury fiber collections on ethnographic textiles from around the world. In addition to its signature knitwear, the collection also offers a range of romantic dresses and imaginatively handcrafted accessories, all exclusively designed for Peruvian Connection. A complete catalogue of the Holiday 2012 collection is available. For additional images, product details and sample requests, contact Amy Sudlow at (913) 845 6034 or [email protected] Borealis Dress, $299. Beaded Fleur Clutch, $218. Beau Soir Bead Bracelets, $89. 2 Chapin Bustle Skirt, $299. Mirage Cable Sweater, $160. Skinny Stitched Belt, $69. Treasure Trove Bracelets, $169. 3 Legacy Lace Skirt, $349. Modernist Top, $159. Tasseled Crochet Belt, $129. 4 Maxim Sheath Dress, $598. Bartlett Shrug, $169, Starlight Disc Earrings, $218. 5 Bellamy Jacket, $298. Bronze Ice Jeans, $179. Crystal Mobile Hoops, $129. 6 Zoe Pullover, $118. Zoe Pants, $99. Chuska Fringe Necklace, $69. 7 Ismène Top, $49. Suspension Earrings, $69. Gold Glam Headband, $29. Art Deco Clutch, $149. 8 Paxton Stripe Cardigan, $149. Tompkins Pants, $159. Light Jersey Shirt, $59. rerspedit aliciis dolo minia doluptate ex endit officaborpos ullibus sum fugitio volum qui beatio bla di 9 Ferrara Swing Coat, $499. Rivington Bag, $369. 10 Chamonix Shearling Jacket, $1,495. Paisley Pencil Cords, $169. Courchevel Fur Hat, $99. 11 Ombré Dress, $79. Marston Beret, $59. Estefania Bag, $159. Pearl-Tipped Tassel Necklace, $149. 12 San Rafael Cardigan, $229. Skinny Jeans, $149. Walnut Foldover Clutch, $149. 13 Fair Isle Tie Waist Cardigan, Amélie Top, $149. Matelassé $279. Tatiana Top, $149. Cropped Trousers, $169. -

Pauline Hoggarth Phd Thesis

3;<;>8D2<;B= ;> 42<42# 56@2AC=6>C ?7 4DE4?# @6AD @2D<;>6 9?882AC9 2 CMJVNV BXGQNWWJI KSU WMJ 5JLUJJ SK @M5 FW WMJ DRNYJUVNW\ SK BW 2RIUJZV (/.* 7XPP QJWFIFWF KSU WMNV NWJQ NV FYFNPFGPJ NR AJVJFUHM1BW2RIUJZV07XPPCJ[W FW0 MWWT0&&UJVJFUHM$UJTSVNWSU\%VW$FRIUJZV%FH%XO& @PJFVJ XVJ WMNV NIJRWNKNJU WS HNWJ SU PNRO WS WMNV NWJQ0 MWWT0&&MIP%MFRIPJ%RJW&('')*&-+,- CMNV NWJQ NV TUSWJHWJI G\ SUNLNRFP HST\UNLMW CMNV NWJQ NV PNHJRVJI XRIJU F 4UJFWNYJ 4SQQSRV <NHJRHJ BILINGUALISM IN CALCA, DEPARTMENT OF CUZCO, PERU by Pauline Hoggarth A dissertation presented in application for the Degree of Ph. D. in the University of St. Andrews Centre for Latin American Linguistic Studies, University of St. Andrews. June 1973 BEST CO" AVAILABLE Certificate I hereby certify that Pauline F. Hoggarth has spent nine terms engaged in research work under my direction and that she has fulfilled the conditions of the General Ordinance No. 12 (Resolution of the University Court No. 1) 1967), and that she is qualified to submit the accompanying thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. (gad.) Declaration I hereby declare that the following thesis is based on work carried out by me, that the thesis is my own composition, and that no part of it has been presented previously for a higher degree. The research was conducted in Peru, London and the Centre for Latin American Linguistic Studies, University of St. Andrews, under the direction of Mr. D. J. Gifford. (8ga") Candidate TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface Acknowledgements i and .... .... ." "" "" iv List of Abbreviations .... .... .... .... I. INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ... -

Peru Compress

INCALINK PACK COUNTRY-MINISTRIES-DEVOTIONALS ACTIVITIES-CRAFTS-RECIPES Welcome to Peru! Well, virtually at least. We are so excited to share the Peruvian culture with you as well as have you parti- cipate in some activities to help you do missions from home! This document includes a variety of crafts, family activities, devotionals, as well as information about one of the countries where we do missions work. These activi- ties can be done in any order (unless otherwise specified), but we recommend you complete one devotional per week so you can put them into practice during the week and apply them as you do some of the activities! We hope you enjoy it! We would love to see how some of your projects turn out, so if you send pictures or videos of the crafts to Luke Schriefer at [email protected], we will send you a free bracelet! If you post your crafts on social media, please be sure to tag our page on Facebook at @incalinkinternational and @incalinkperu, and on Instagram or Twitter at @inca_link. INCA LINK INCALINK PACK PACK DEVOTIONALS on “The Great Commission” This study was prepared by Rich and Elisa Brown. The Browns serve as regio- nal missionaries in Latin America to reach the 300 million youth in Latin America. As Family a family, their favorite thing to do is play card games or Spikeball. What they love Study most about Latin America are their friends. Both were born and raised there. Title: you can run, 1 but you Jonah can't hide. passage prayer: Dear Jesus, thank you for giving us hope in this life, of the day and in the one to come. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

Enlaced and Interwoven Clothing from Southern Abya Yala

ENLACED AND INTERWOVEN CLOTHING FROM SOUTHERN ABYA YALA 1 VERNETZT VERSTRICKT VERWOBEN ANZIEHENDES AUS DEM SÜDLICHEN ABYA YALA © Museum Fünf Kontinente 2020 Enlaced and Interwoven. Clothing from Southern Abya Yala Clothing and adornment from various The origins of Latin American textile Guatemala and the Guna of Panama and resources. However, advancements times and regions are presented in traditions predate the European invasi- represent the visualisation of changing in human rights that were achieved in this exhibition room, illustrating the on by millennia, and are closely related identities in woven and embroidered the past decades are at stake today, aesthetics and artistic diversity of indi- to Latin America’s chequered history patterns. Clothing and jewellery of the and the increasing pressure on indige- genous creativity in Latin America. At and vibrant present. A small selection Mapuche tell of lasting resistance from nous communities has assumed a level the same time they represent ways to of pre-Columbian weaving products the time of Inca expansion to the colo- that once again threatens their exis- master the challenges posed by the en- gives an impression of their import- nial era and into the present. tence. vironment and by communal life. Clot- ance in long-ago times. The fusion hing can protect from cold and heat, of indigenous and colonial-European Many indigenous philosophers and This exhibition is intended to present it has the ability to either conceal its fashions, which at times has a tongue- activists have come to oppose the term examples allowing an impression of wearer from view or to attract glances, in-cheek undertone, is represented by “America”, which is criticized for being the diversity of “getting dressed”, and it can be either exclusive or inclusi- creations from the Andes of Bolivia and ethnocentric, with Abya Yala, “Land in of topics associated with dressing. -

The Light of Unity

, , A BAHaA BAHa` i ` COM` i ` COMPANIONPANION FOR FOR YOUNG YOUNG EXPLORE EXPLORERs Rs wwwww.brilliantstarmagazine.w.brilliantstarmagazine.ororg g VOLV. 48,OL. N48O . NO.2 2 QUIZ YOURSELF THELIGHT LIGHT ON EQUALITY HOW DO YOU SPEAK OFOF UNITYUNITY UP FOR JUSTICE? tt tt BAHÁ’Í NATIONAL CENTER 1233 Central Street, Evanston, Illinois 60201 U.S. 847.853.2354 [email protected] WHAT’S INSIDE Subscriptions: 1.800.999.9019 www.brilliantstarmagazine.org Published by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States FAVORITE FEATURES Amethel Parel-Sewell EDITOR/CREATIVE DIRECTOR C. Aaron Kreader DESIGNER/ILLUSTRATOR Bahá’u’lláh’s Life: Mission of Peace am4 He faced prejudice with faith and courage. Amy Renshaw SENIOR EDITOR Susan Engle ASSOCIATE EDITOR Annie Reneau ASSISTANT EDITOR Nur’s Nook Foad Ghorbani PRODUCTION ASSISTANT 6 Make a string of stars to celebrate diversity. MANY THANKS TO OUR CONTRIBUTORS: Amia Allmart • Brian Beasley • Haley Berkowitz Lisa Blecker • Dr. Robert Bullard • Johnny Cornyn Maya’s Mysteries Francisco Cotto • Darlene Gait • Andrea Hope Nadia Khazei • Lyla Kitchens • Danny Lapidus 10 There may be 100 million species on Earth! Jhian Mahboubi • Doug Marshall • Jim Neeb Eliana Paik • Lucia Pane • Kai Parel-Sewell Paz Parel-Sewell • Layli Phillips • Donna Price We Are One Dr. Stephen Scotti • Haley-Grace Wu • Arshan Lee Yeganegi 11 Explore and care for the place we all call home. ART AND PHOTO CREDITS Original illustrations by C. Aaron Kreader, unless noted By Lisa Blecker: Photos for pp. 6-7; Watercolor for p. 10; Radiant Stars Inking and watercolor for p. -

2 0 1 5 M E D I a G U I

2015 MEDIA GUIDE RACING JULY 16 - SEPT 7 & OCT 29 - NOV 29 Del Mar Stakes Schedule – 76th Summer Season – 2015 .83 112 Date Event Conditions Distance Purse .. Thu. Jul. 16 OCEANSIDE STAKES Three-year-olds, N/W S/S of $50,000 at 1 M o/o 1 Mile (Turf) $100,000 A .........2,788 in 2015 Sat. Jul. 18 Osunitas Stakes Fillies & Mares, Three-year-olds & up, N/W S/S 1 1/16 Miles (Turf) $80,000 A ....................320 of $50,000 at 1 M o/o in 2015 Sat. Jul. 18 EDDIE READ STAKES (Gr. I) Three-year-olds & up 1 1/8 Miles (Turf) $400,000 G Baltimore ..................2,730 Baltimore City New York Auto Miles to Del Mar:Auto ......................17 Oceanside ......................20 San Diego ..........................34 Tijuana ......48 San Juan Capistrano ........................79 Anaheim Los Alamitos (Cypress) .........97 Barretts (Pomona) Anita Santa (Arcadia) ..............199 Santa Barbara Las Vegas .......................367Phoenix ..............484 San Francisco ................784 Albuquerque ....................1,065 Portland .......................1,237 Seattle .......................1,370 Dallas .............1,821 New Orleans ....................2,041 Chicago .................2,104 Louisville .......................2,655 Miami Sun. Jul. 19 SAN CLEMENTE HANDICAP (Gr. II) Fillies, Three-year-olds 1 Mile (Turf) $200,000 G N Wed. Jul. 22 Wickerr Stakes Three-year-olds & up, N/W S/S $50,000 at 1 M 1 Mile (Turf) $80,000 A o/o since March 1 Fri. Jul. 24 COUGAR II HANDICAP (Gr. III) Three-year-olds & up 1 1/2 Miles $100,000 G INTERSTATE 5 Sat. Jul. 25 FLEET TREAT STAKES Fillies,Three-year-olds, Cal-Bred 7 Furlongs $200,000 G Del Mar is located just west of I-5 at 20 Valle, de la Via miles north of San Diego and 100 miles south of Angeles. -

Discovery Chest Artifact Description Cards Carved Gourd (Peru) in Which Country Or Region Is This Used? • the Ayacucho Area of the Central Andes

Latin America Discovery Chest Artifact Description Cards Carved Gourd (Peru) In which country or region is this used? • The Ayacucho Area of the Central Andes. What is this? • Gourds are vegetables similar to squash and pumpkins. When they dried, they were used as storage containers. People would often decorate them with carvings of daily life and religious symbols. What is its significance? • Since ancient Peruvians believed in life after death, they thought it very important to put gourds filled with food and water in the graves of people who died, because they would need these in the afterlife. Latin America 1A – CRAFTS Miniature Backstrap Loom (Peru) In which country or region is this used? • In the Cuzco area of Highland Peru. What is this? • The loom was a tool to help people make highly complicated weavings. It is made from cotton and wood. How is it used? • A set of wooden sticks, called heddles, controls a selected sequence of threads in the wrap, the vertical part of the loom. The manipulation of these heddles combined with the insertion of a weft, horizontal, threads result in woven fabric. What is its significance? • Pre-Columbian textiles tell the stories and histories of how the Peruvians lived, what they believed, who their leaders were, and what their aesthetic sense was. In addition, gifts of woven cloth were offered at marriages, among other rituals, and to form political, social, and religious alliances. Latin America 2A – CRAFTS Faja (Belt) (Guatemala) Who used this item? • The Jacaltec-speaking Highland Maya in the Departamento of Huechuetenango Guatemala. -

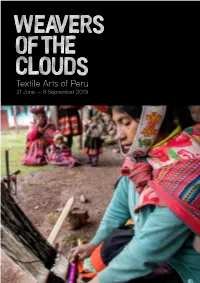

FTM-WOTC-Handout-V5.Pdf

Credits Guest Curator: Hilary Simon With special thanks to: Head of Exhibitions: Alice Viera Albergaria Costa Borges Dennis Nothdruft Annie Hurlbut, Peruvian Connection Exhibition Design: Beth Ojari Armando Andrade Garment Mounting and Conservation: Camilo Garcia, IAG Cargo Gill Cochrane Carlos Agusto Dammert, Hellmann Exhibitions Coordinator: Marta Martin Soriano Worldwide Logistics Caryn Simonson, Chelsea College of Art Curator of ‘A Thread: Contemporary Art of Peru’: H.E Juan Carlos Gamarra Ambassador Claudia Trosso of Peru to Great Britain Jaime Cardenas, Director of Peru Trade Graphic Design: Hawaii and Investment Office Set Build and Installation: Setwo Ltd Leonardo Arana Yampe Graphic Production: Display Ways Mari Solari Handout Design: Madalena Studio Martin Morales Peruvian Embassy Head of Commercial and Operations: Promperú Melissa French Samuel Revilla and Luis Chaves, KUNA Operations Manager: Charlotte Neep Soledad Mujica Press and Marketing Officer: Philippa Kelly Susana de la Puente Front of House Coordinator: Vicky Stylianides Retail and Events Officer: Sadie Doherty Gallery Invigilation: Abu Musah PR Consultant: Penny Sychrava WEAVERS OF THE CLOUDS is a Fashion and Textile Museum exhibition Cover: ©Awamaki/Brianna Griesinger. Opposite: ©Mel Smith Opposite: Griesinger. ©Awamaki/Brianna Cover: Glossary of Peruvian Costume Women’s Traditional Dress Men’s Traditional Dress Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Camisa/blusa – a blouse. Buchis – short pants adapted from Spanish costume, which, Chumpi – a woven belt. depending on the area, come to the knee or a little longer. Juyuna – wool jackets that are worn under the women’s Centillo – finely decorated hat bands. shoulder cloths, with front panels decorated with white buttons. -

Ch'ullus in Cosco: Identity in the Andes

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-23-1999 Ch'ullus in Cosco: Identity in the Andes Susan M. Kaesgen Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the American Art and Architecture Commons, and the Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons Recommended Citation Kaesgen, Susan M., "Ch'ullus in Cosco: Identity in the Andes" (1999). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 25. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/25 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ch 'ullus in Cosco: Identity in the Andes by Susan M. Kaesgen FINAL PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THEDEG REE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES SKIDMORE COLLEGE April 1999 Advisors : Lisa Aronson, Phd. & Patrice Rubio, Phd. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 2 LIST OF FIGURES 3 INTRODUCTION 6 TEXT 9 BIBLIOGRAPHY 61 ABSTRACT This study centers on the ch 'uffu, the knitted cap, usually with ear flaps and an elongated peak or tail, a hat that identifies the wearer as an indigenous Anden male. The long history of the ch 'ulluis marked by both its use as geographic identifier, and as a canvas upon which to present the same designs that represent ancient Andean ideas about ancestory, land and time. Because the knitted hats of today functionexactly as ancient ones did, the ch 'ulluis proven a descendant of ancient hats, an important element to be preserved rather than discarded for factory made caps .