1 Railways and Tourism in Belgium, 1835

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CFE Annual Report

Annual Report 2009 129 th corporate financial year Proud of their many realisations, the teams of the CFE group are pleased to present the activity report for the year 2009. Compagnie d’Entreprises CFE SA Founded in Brussels on June 21, 1880 Headquarters: 42, avenue Herrmann-Debroux, 1160 Brussels – Belgium Company number 0400.464.795 RPM Brussels Telephone: +32 2 661 12 11 Fax: +32 2 660 77 10 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.cfe.be 1 Edito As expected, the CFE group’s 2009 revenue and profit came in below those of the previous year, when it achieved its best-ever perform- ance. However, the decline in revenue (€ -125 million), operating profit (€ -19.3 million) and net after-tax profit (€ -8.2 million) was modest against the backdrop of the global economic crisis. All divisions made a positive contribution to profit. DEME deserves special recognition for again demonstrating its ability to strengthen its position in the international dredging market, fully vindicating the substantial investments made in recent years to modernise its fleet. CFE has many strengths that enable it to weather the economic crisis and move confidently into 2010. The order book, standing at € 2,024 million, is satisfactory, although construction activity is likely to decline from the 2009 level. We intend to resist the temptation to take orders at any price, concentrating instead on profit. To do this, our recent international expansion, especially in Tunisia, holds out good prospects for repositioning our activity. CFE’s broad diversity of business lines and geographical locations is an additional asset, as is our sound financial position, which shields us from liquidity problems. -

The Schooling of Roma Children in Belgium

The schooling of Roma children in Belgium The parents’ voice The schooling of Roma children in Belgium The parents’ voice COLOFON Schooling of Roma children in Belgium. The parents’ voice. Deze publicatie bestaat ook in het Nederlands onder de titel: Scholing van Romakinderen in België. Ouders aan het woord Cette publication est également disponible en français sous le titre: Scolarisation des enfants roms en Belgique. Paroles de parents A publication of the King Baudouin Foundation, rue Brederode 21, 1000 Brussels AUTHOR Iulia Hasdeu, doctor in antropology, Université de Genève EDITORIAL CONTRIBU- Ilke Adams, researcher, METICES-GERME, Institut de sociologie, ULB TION CHAPTER 5 TRANSLATION Liz Harrison COORDINATION Françoise Pissart, director KING BAUDOUIN FOUN- Stefanie Biesmans, project collaborator DATION Brigitte Kessel, project manager Nathalie Troupée, assistant Ann Vasseur, management assistant GRAPHIC CONCEPT PuPiL LAYOUT Tilt Factory PRINT ON DEMAND Manufast-ABP, a non-profit, special-employment enterprise This publication can be downloaded free of charge from www.kbs-frb.be A printed version of this electronic publication is available free of charge: order online from www.kbs-frb.be, by e-mail at [email protected] or call King Baudouin Foundations’ Contact Center +32-70-233 728, fax + 32-70-233-727 Legal deposit: D/2893/2009/07 ISBN-13: 978-90-5130-641-5 EAN: 9789051306415 ORDER NUMBER: 1857 March 2009 With the support of the Belgian National Lottery FOREWORD Roma children… If ever there was a complex issue, conducive to controversy and prejudice, it is this. The cliché of parents exploiting their children by forcing them to beg dominates our perceptions. -

Planning for Agglomeration Economies in a Polycentric Region: Envisioning an Efficient Metropolitan Core Area in Flanders, European Journal of Spatial Development, 69

Refereed article The European Journal of Spatial No. 69 Development is published by August 2018 Nordregio, Nordic Centre for Spatial Development and Delft University of Technology, Faculty of Architecture and Built Environment. To cite this article: Boussauw, K., Van Meeteren, M., Sansen, J., Meijers, E., Storme, T., Louw, E., Derudder, ISSN 1650-9544 B. & Witlox, F. (2018). Planning for agglomeration economies in a polycentric region: Envisioning an efficient metropolitan core area in Flanders, European Journal of Spatial Development, 69. Publication details, including Available from: http://doi.org/10.30689/EJSD2018:69.1650-9544 instructions for authors: http://www.nordregio.org/ejsd Online publication date: August 2018 Indexed in Scopus, DOAJ and EBSCO Planning for agglomeration economies in a polycentric region: Envisioning an efficient metropolitan core area AUTHOR INFORMATION Kobe Boussauw, Joren in Flanders Sansen Cosmopolis Centre for Urban Kobe Boussauw, Michiel van Meeteren, Joren Sansen, Evert Meijers, Research - Department of Tom Storme, Erik Louw, Ben Derudder, Frank Witlox Geography, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium Email: Abstract [email protected], To some degree, metropolitan regions owe their existence to the ability [email protected] to valorize agglomeration economies. The general perception is that agglomeration economies increase with city size, which is why economists Michiel van Meeteren tend to propagate urbanization, in this case in the form of metropolization. Department of Geography, Contrarily, spatial planners traditionally emphasize the negative Loughborough University, consequences of urban growth in terms of liveability, environmental quality, Loughborough, UK and congestion. Polycentric development models have been proposed Email: m.van-meeteren@ as a specific form of metropolization that allow for both agglomeration lboro.ac.uk economies and higher levels of liveability and sustainability. -

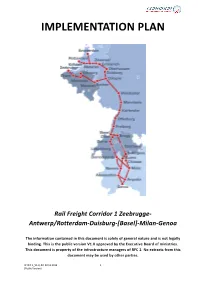

Implementation Plan

IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Rail Freight Corridor 1 Zeebrugge- Antwerp/Rotterdam-Duisburg-[Basel]-Milan-Genoa The information contained in this document is solely of general nature and is not legally binding. This is the public version V1.0 approved by the Executive Board of ministries. This document is property of the infrastructure managers of RFC 1. No extracts from this document may be used by other parties. IP RFC 1_V1.0, dd. 03.12.2013 1 (Public Version) Implementation Plan RFC 1 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2 CORRIDOR DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 CORRIDOR LINES ............................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Routing ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1.2 Traffic Demand ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 2.1.3 Bottlenecks ................................................................................................................................................................... 18 2.1.4 Available Capacity ........................................................................................................................................................ -

Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport Directorate General For

Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport Directorate General for Land Transport Department for Railway Safety and Interoperability Vooruitgangstraat 56 1210 Brussels www.mobilit.fgov.be Lay out: de facto image building Annual Report 2010 of the Belgian Safety Authority Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport Table of contents A/ Preface 4 1. Scope of the Report 4 2. Summary 5 B/ Introduction 6 1. Introduction to the report 6 2. Information on the Railway Structure (Annex A) 6 3. Summary - Overall trend analysis 7 C/ Organisation 8 1. Presentation of the organisation 8 2. Organisation chart 10 D/ Evolution of railway safety 11 1. Initiatives to improve safety performance 11 2. Detailed trend analysis 12 3. Results of the safety recommendations 13 E/ Major adjustments 14 to legislation and regulations F/ Development of safety 16 certification and authorisations 1. National legislation - start and expiry dates 17 2. Numerical data 17 3. Procedural aspects 18 G/ Supervision of railway undertakings 22 and infrastructure managers H/ Report on the application of 24 the CSM on risk analysis and assessment I/ Decisions of the DRSI: Priorities 25 J/ Information sources 26 K/ Annexes 27 33 A/ Preface 1/ Scope of the Report This report describes the activities of the Belgian Safety Authority in 2010. It was prepared by the Department for Railway Safety and Interoperability (DRSI). The DRSI is a department of the Directorate-General for Land Transport, which is part of the Federal Public Service Mobility and Transport. By Royal Decree of 16 January 2007, the DRSI has been appointed as the National Safety Authority (NSA). -

Capacity Bottleneck Analysis 2020, RFC Rhine-Alpine

RFC Rhine-Alpine Development of Capacity Bottlenecks State of play 2020 Version 2.0 01 March 2021 WG Infrastructure and Terminals (WG I&T) with WG Train Performance Management 1 Capacity Bottleneck Analysis 2020, RFC Rhine-Alpine Introduction The calculation of bottlenecks for rail infrastructure is quite complicated. National calculation methodologies at IMs and national decision processes on infrastructure development are different and a common bottleneck analysis for RFC Rhine-Alpine turned out to be an impossible task. Therefore the MB of RFC Rhine-Alpine decided to set up the present CBA on the basis of the national investment plans to identify the infrastructural bottlenecks. This is a joint corridor approach, consisting of a combination of the national information provided by the different IMs. The information has been compiled by the WG Infrastructure & Terminals and can be found in part A of the present document. In addition, the perspective of the Railway Undertakings to the Capacity Bottleneck analysis was added as a result from an enquiry of the European Commission in 2019 and completed with a list of additional bottlenecks identified by the RU’s in 2020. In addition, part B gives an overview of additional operational bottlenecks out of an analysis of the WG Train Performance Management. The idea of this additional information is to give a more comprehensive overview of the different bottlenecks which might be encountered by the users of RFC Rhine-Alpine. PART A : Infrastructural bottlenecks The WG-members gave information on the expected Capacity Bottlenecks in the future years for their own countries. Presenting this information in jumping jacks (JJ’s) showing where the Capacity Bottlenecks can be found on the entire corridor. -

Regional Development Programmes Belgium 1978-1980

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES programmes Regional development programmes Belgium 1978-1980 REGIONAL POLICY SERIES - 1979 14 COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Regional development programmes Belgium 1978-1980 COLLECTION PROGRAMMES Regional Policy Series No 14 Brussels, November 1978 NOTE It is appropriate first of all to draw the reader's attention to the essentially indicative character of these regional development programmes. This publication is also available in DE ISBN 92-825-0960-5 FR ISBN 92-825-0962-1 NL ISBN 92-825-0963-X Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this volume © Copyright ECSC - EEC - EAEC, Brussels - Luxembourg, 1979 Reproduction authorized, in whole or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Luxembourg ISBN 92-825-0961-3 Catalogue number: CB-NS-79-014-EN-C Contents GENERAL INTRODUCTION 5 Detailed index 7 A. Socio-economic development trends in Belgium, 1960-1977 9 B. National political options 11 C. The regional development programmes 12 D. The constitutional institutions 15 Annexes 21 Maps 33 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FLANDERS 1978-1980 37 Detailed index 39 Chapter I - Economic and social analysis 43 Chapter II - Development objectives 91 Chapter III - Development measures 105 Chapter IV - Financial resources 129 Chapter V - Implementation of the programme 139 Annex 145 REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME WALLONIA 1978-1980 147 Detailed index 149 Chapter I - Economic and social analysis 151 Chapter II - Development objectives 189 Chapter III - Development measures 193 Chapter IV - Financial resources 201 Chapter V - Implementation of the programme 207 Annexes 213 General introduction Detailed index A. Socio-economic development trends in Belgium, 1960-1977 9 B. -

TRAFFICKING in and $MUGGLING of HUMAN BEING$ in a Haze of Legality

TRAFFICKING IN AND $MUGGLING OF HUMAN BEING$ In a haze of legality ANNUAL REPORT 2009 CENTRE FOR EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES AND OPPOSITION TO RACISM INTRODUCTION 6 PART 1: EVOLUTION OF THE PHENOMENON AND THE COMBAT AGAINST TRAFFICKING IN HUMAN BEINGS 10 Chapter 1: Recent developments in the legal and policy framework concerning the traf!cking in and smuggling of human beings 12 Chapter 2: Phenomenon analysis 14 !" #$%&\()*+, *+ -./%+ 01*+,2 &3$ 4-1 5.$53212 3& 216.%7 16573*4%4*3+ 16 1.1. General trends 16 1.2. The professionalisation of networks 16 1.3. Learning organisations: structures 17 !"8"!" 9%:%/2 17 !"8";" <1+4 18 !"8"8" =3,.2 217&>1/573?/1+4 18 !"8"@" RB-%/5%,+1 0%$2S 18 !"8"D" E$3+4 /1+ 19 !"8"F" <12*:1+(1 51$/*42 19 !"#" $%&'%()S +,-\/0) 19 !"@"!" G*+>H*+ 2*4.%4*3+2 19 !"@";" I*(4*/2 3& 73J1$03?2 20 !"@"8" K$.,>:151+:1+4 J*(4*/2 20 !"@"@" L*::1+ J*(4*/2 20 !"@"D" B.74.$1>0%21: 2.0/*22*3+ 21 !"@"F" K104 03+:%,1 21 !"@"M" E3$(1: 5$324*4.4*3+ 21 !"@"N" O+:1$>%,1: J*(4*/2 3& 5$324*4.4*3+ 22 ;" #$%&\()*+, *+ -./%+ 01*+,2 &3$ 4-1 5.$53212 3& 7%03.$ 16573*4%4*3+ 23 2.1. General trends 23 2.2. Professional networks 23 1"2" $%&'%()S +,-\/0) 24 2.4. Sectors 24 ;"@"!" P,$*(.74.$1 %+: -3$4*(.74.$1 24 ;"@";" B3+24$.(4*3+ %+: $1+3J%4*3+ 24 ;"@"8" #-1 L3417 N <124%.$%+4 N B%41$*+, 21(43$ RLS<TBPU 26 ;"@"@" #164*712 26 ;"@"D" K3/124*( H3$) 26 ;"@"F" #$%+253$4 27 ;"@"M" V*,-4 2-352 %+: 5-3+1 2-352 27 ;"@"N" B%$ H%2-12 28 ;"@"W" =%)1$*12 %+: 0.4(-1$2S 2-352 28 ;"@"!X" #-1 (71%+*+, *+:.24$? 28 ;"@"!!" #3*714 21$J*(12 29 ;"@"!;" Y14$37 24%4*3+2 29 ;"@"!8" G%241 5$3(122*+, 29 ;"@"!@" #-1 /1%4 5$3(122*+, *+:.24$? 29 8" S4-1$ &3$/2 3& 16573*4%4*3+ 30 3.1. -

Implementation Plan - Update December 2020

Corridor Information Document - Implementation Plan - Update December 2020 “RFC North Sea – Med is co-financed by the European Union's CEF. The sole responsibility of this publication lies with the author. The European Union is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein” CID Implementation Plan – 01/01/2021 Version Control Version Chapter changed Changes 20/11/2020 Review 1 Permanent - Based on the last final version published team (TT 2020); - Extension from Ghent to Terneuzen as connecting line in 2019; - With the withdrawal of the United Kingdom out of the European Union, and by consequence the leave as members of Network Rail and Eurotunnel, the content of this book has been adapted accordingly. 27/11/2020 Review 2 - Changes have been made on the basis of Management Board the input and comments provided by the for review by members of the Management Board; Executive Board and - This version has been sent to the in parallel Executive Board members for review; Stakeholder - In parallel, this reviewed version has been consultation sent out for stakeholder consultation. 10/12/2020 Final Draft - Changes have been made on the basis of the input and comments provided by the members of the Executive Board; - Changes have been made on the basis of comments received during the Stakeholder consultation. 17/12/2020 Final version The final version has been approved by approved by the the Executive Board for publication on the Executive board for website on 01/01/2021. publication on the website 01/01/2021 Publication on the website CID Implementation Plan – 01/01/2021 2 of 44 Table of Contents 1. -

Economic Importance of the Belgian Ports: Flemish Maritime Ports, Liège Port Complex and the Port of Brussels - Report 2014

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics van Gastel, George Working Paper Economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels - Report 2014 NBB Working Paper, No. 299 Provided in Cooperation with: National Bank of Belgium, Brussels Suggested Citation: van Gastel, George (2016) : Economic importance of the Belgian ports: Flemish maritime ports, Liège port complex and the port of Brussels - Report 2014, NBB Working Paper, No. 299, National Bank of Belgium, Brussels This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/144511 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Liefkenshoek Link in Antwerp | TUC RAIL

Liefkenshoek link in Antwerp Description The Liefkenshoek railway link project consisted in the construction of a direct railway link between the left and right banks of the River Scheldt. The new railway link directly connects the left bank with the railway infrastructure on the right bank (Line 11 and the Antwerpen Noord marshalling yard) without trains having to leave the port area. This freight link must provide a solution for the expected increase of rail freight traffic to and from the port of Antwerp. The developments on the left bank, more specifically the commissioning of Deurganck Dock, are one reason. At the same time, policy-makers are also striving to increase the share of rail transport in freight transport. Without the Liefkenshoek railway link the additional freight traffic that would be generated as a result would have an unacceptable impact on train traffic on the current route via the Antwerp-Ghent railway line (Line 59, passenger traffic). The construction of this infrastructure in the port will make it possible to increase the share of rail freight as well as reducing the risk of structural traffic congestion in the region around Antwerp. The railway link consists of a new 16.2-km double-track railroad which passes under three waterways: the Waasland Canal on the left bank, the River Scheldt and Kanaal Dock on the right bank. As a result half of the new line runs underground, in tunnels. The existing Beveren Tunnel (which had not been operated till then) will be used to pass under the Waasland Canal. For the most part the railway line will be bundled with the existing road infrastructure. -

Belgium Through the Lens of Rail Travel Requests: Does Geography Still Matter?

Article Belgium through the Lens of Rail Travel Requests: Does Geography Still Matter? Jonathan Jones 1, Christophe Cloquet 2, Arnaud Adam 1, Adeline Decuyper 1 and Isabelle Thomas 1,3,* 1 Center for Operations Research and Econometrics, Université catholique de Louvain, Voie du Roman Pays 34, 1348 Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; [email protected] (J.J.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 Poppy, rue Van Bortonne 7, 1090 Bruxelles, Belgium; [email protected] 3 F.N.R.S. (Fond National de la Recherche Scientifique), Rue d’Egmont 5, 1000 Bruxelles, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-10-474326 Academic Editors: Bin Jiang, Constantinos Antoniou and Wolfgang Kainz Received: 14 September 2016; Accepted: 3 November 2016; Published: 15 November 2016 Abstract: This paper uses on-line railway travel requests from the iRail schedule-finder application for assessing the suitability of that kind of big data for transportation planning and to examine the temporal and regional variations of the travel demand by train in Belgium. Travel requests are collected over a two-month period and consist of origin-destination flows between stations operated by the Belgian national railway company in 2016. The Louvain method is applied to detect communities of tightly-connected stations. Results show the influence of both the urban and network structures on the spatial organization of the clusters. We also further discuss the implications of the observed temporal and regional variations of these clusters for transportation travel demand and planning. Keywords: big data; railway transport; Belgium; Louvain method 1.