SDSU Template, Version 11.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Racism and Stereotypes: Th Movies-A Special Reference to And

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific ResearchResearch Larbi Ben M’h idi University-Oum El Bouaghi Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of English Racism and Stereotypes: The Image of the Other in Disney’s Movies-A Special Reference to Aladdin , Dumbo and The Lion King A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D egree of Master of Arts in Anglo-American Studies By: Abed Khaoula Board of Examiners Supervisor: Hafsa Naima Examiner: Stiti Rinad 2015-2016 Dedication To the best parents on earth Ouiza and Mourad To the most adorable sisters Shayma, Imène, Kenza and Abir To my best friend Doudou with love i Acknowledgements First of all,I would like to thank ‘A llah’ who guides and gives me the courage and Patience for conducting this research.. I would like to express my deep appreciation to my supervisor Miss Hafsa Naima who traced the path for this dissertation. This work would have never existed without her guidance and help. Special thanks to my examiner Miss Stiti Rinad who accepted to evaluate my work. In a more personal vein I would like to thank my mother thousand and one thanks for her patience and unconditional support that facilitated the completion of my graduate work. Last but not least, I acknowledge the help of my generous teacher Mr. Bouri who believed in me and lifted up my spirits. Thank you for everyone who believed in me. ii ا ا أن اوات ا اد ر ر دة اطل , د ه اوات ا . -

Disney Magic Becomes a Little Less Magical and a Little More

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo HOHONU 2019 Vol. 17 majority of Disney films often bequeath the antagonist of Disney Magic Becomes a Little the storyline with a non-American accent, exemplified Less Magical and a Little More by Shere Khan’s British accent in The Jungle Book. The protagonists of the films, like Mowgli in The Jungle Book, Discriminatory are almost always portrayed with the Standard American Kaleigh Anderson accent. It has been a common pattern within Disney’s animated features that characters who speak with non- Storytelling is a crucial part for humankind as well Standard American accents are portrayed as outsiders, as in oral history. Movie adaptations have also become and are selfish and corrupt with the desire to seek or a key ingredient in relaying certain messages to people obtain power. This analysis is clearly displayed in one of of all ages. However, children watching movies and Disney’s most popular animated feature films, The Lion absorbing stories are susceptible and systematically King. In this Hamlet-inspired tale, the main characters’ exposed to a standard (or specific) language ideology accents bring attention to which characters fall into by means of linguistic stereotypes in films and television the “good guy” versus “bad guy” stereotype. Simba, shows. These types of media specifically, provide a the prized protagonist in the film, and Nala, his love wider view on people of different races or nationalities interest, both speak Standard American dialects. Through to children (Green, 1997). Disney films, for instance, linguistic production, Simba’s portrayal as the Lion King are superficially cute, innocent and lighthearted, but translates an underlying message to children viewers through a deeper analysis , the details of Disney movies that characters who are portrayed as heroes or heroines provide, a severe, and discriminating image. -

Animated Stereotypes –

Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Alexander Lindgren, 36761 Pro gradu-avhandling i engelska språket och litteraturen Handledare: Jason Finch Fakulteten för humaniora, psykologi och teologi Åbo Akademi 2020 ÅBO AKADEMI – FACULTY OF ARTS, PSYCHOLOGY AND THEOLOGY Abstract for Master’s Thesis Subject: English Language and Literature Author: Alexander Lindgren Title: Animated Stereotypes – An Analysis of Disney’s Contemporary Portrayals of Race and Ethnicity Supervisor: Jason Finch Abstract: Walt Disney Animation Studios is currently one of the world’s largest producers of animated content aimed at children. However, while Disney often has been associated with themes such as childhood, magic, and innocence, many of the company’s animated films have simultaneously been criticized for their offensive and quite problematic take on race and ethnicity, as well their heavy reliance on cultural stereotypes. This study aims to evaluate Disney’s portrayals of racial and ethnic minorities, as well as determine whether or not the nature of the company’s portrayals have become more culturally sensitive with time. To accomplish this, seven animated feature films produced by Disney were analyzed. These analyses are of a qualitative nature, with a focus on imagology and postcolonial literary theory, and the results have simultaneously been compared to corresponding criticism and analyses by other authors and scholars. Based on the overall results of the analyses, it does seem as if Disney is becoming more progressive and culturally sensitive with time. However, while most of the recent films are free from the clearly racist elements found in the company’s earlier productions, it is quite evident that Disney still tends to rely heavily on certain cultural stereotypes. -

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

From Snow White to Frozen

From Snow White to Frozen An evaluation of popular gender representation indicators applied to Disney’s princess films __________________________________________________ En utvärdering av populära könsrepresentations-indikatorer tillämpade på Disneys prinsessfilmer __________________________________________________ Johan Nyh __________________________________________________ Faculty: The Institution for Geography, Media and Communication __________________________________________________ Subject: Film studies __________________________________________________ Points: 15hp Master thesis __________________________________________________ Supervisor: Patrik Sjöberg __________________________________________________ Examiner: John Sundholm __________________________________________________ Date: June 25th, 2015 __________________________________________________ Serial number: __________________________________________________ Abstract Simple content analysis methods, such as the Bechdel test and measuring percentage of female talk time or characters, have seen a surge of attention from mainstream media and in social media the last couple of years. Underlying assumptions are generally shared with the gender role socialization model and consequently, an importance is stated, due to a high degree to which impressions from media shape in particular young children’s identification processes. For young girls, the Disney Princesses franchise (with Frozen included) stands out as the number one player commercially as well as in customer awareness. -

{PDF} Mulan: a Story in Chinese and English

MULAN: A STORY IN CHINESE AND ENGLISH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Li Jian,Yijin Wert | 42 pages | 19 May 2014 | BetterLink Press Incorporated | 9781602209862 | English, Chinese | New York, United States Chinese Tale: Mulan (Original) Chen also says that the title of the poem and the fact that it is named for the female character reflects the respected status that women held in these nomadic societies. One may say the true meaning of the name Mulan is a forgotten legacy of the Tuoba. For around a thousand years, the story more or less stayed the same, a simple, easy-to-understand folk poem popular with the Chinese people. The first known adaptation was in the 16th century, by playwright Xu Wei. It emphasized footbinding, which is not mentioned in the original, as the custom was not widely practiced during the Northern Wei dynasty. The character was later included in a popular 17th-century novel about the Sui and early Tang dynasties, which was a marked departure from the poem. Here, Mulan commits suicide rather than live under a foreign ruler, meeting a tragic end. This version played on gender as well as ideas of national identity against a complicated political backdrop, and some have argued that the renewed interest it sparked in the Mulan story was partly due to its nationalistic overtones and critique of the occupation. Looking back at the original Mulan legend helps explain the criticism over certain stylistic choices in the film, such as the costume and the architecture. For some, the questions over adaptation and historical accuracy are inextricable from the issue of representation, both onscreen and behind the camera. -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

An Analysis of Moral Values in Zootopia Movie

AN ANALYSIS OF MORAL VALUES IN ZOOTOPIA MOVIE THESIS Submitted by: MAULIDIA HUMAIRA Student of Department of English Language Education Faculty of Education and Teacher Training Reg. No: 231324225 FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND TEACHER TRAINING AR-RANIRY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY DARUSSALAM-BANDA ACEH 2018/1439 H ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Alhamdulillah, All praises be to Allah ‘azzawajalla, the most gracious, the most merciful, andthe most beneficent who has given me love and blessing that made me able to finish this research and writing this thesis. Peace and salutation be upon our beloved prophet Muhammad SAW, his family and companions has struggled whole heartedly to guide ummah to the right path. On this occasion with great humility, I would like to thank to all of those who help me and guidance, so that this thesis can be finished in time. Completion of writing this thesis, I would like to thanks Dr. Muhammad Nasir, M.Hum and Mr. T. Murdani, S.Ag, M.IntlDev as my supervisor forgiving the useful supervision, guidance and constructive ideas during the process of completing this thesis. Also I would like to express my gratitude and high appreciation to my beloved father Burhanuddin, and my lovely mother Rasunah for their wisdom, patience, love, attention, support and care. I also bestow my thankfulness to my beloved sisters Puspitasari and Safrida , my brothers Hafidh Kurniawan and Muhammad Irfan, and my cousins Putri Nabila Ulfa and Maulizahra, for their endless love who inspired and motivated me all along accomplishing this thesis. My special thanks to my academic advisor Mr. Dr.Syarwan, M.LIS, who has supervised me since I was first semester until now. -

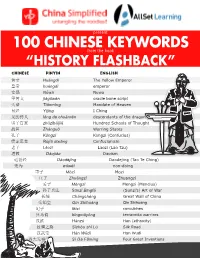

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 1-2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Manling Luo _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Politics of Place-Making _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Politics of Place-Making T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 43-75 www.brill.com/tpao 43 The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang Manling Luo Indiana University The Luoyang qielan ji 洛陽伽藍記 (Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang; hereafter Records), compiled by Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (fl. 547) in roughly 547 CE, commemorates the ruined capital city of the North- ern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534).1 One of the few major works to survive from the period, the Records has received much critical attention, with topics ranging from its textual history to its historical and literary value. This essay focuses on what I call the “politics of place-making” in the memoir, that is, engagements with Luoyang’s space as expressions of power before and after the city’s abandonment, as represented and un- derstood by Yang. These ignored aspects shed light on the central con- cerns that motivated his writing, thereby revealing his perspective on the intersections of place, power, and human agency. The analysis al- lows us to better understand his innovations in pioneering an unofficial, space-centered historiography that defines historical agents as place- makers whose deeds and lives are anchored spatially as much as tempo- rally. -

Empresses, Bhikṣuṇῑs, and Women of Pure Faith

EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH: BUDDHISM AND THE POLITICS OF PATRONAGE IN THE NORTHERN WEI By STEPHANIE LYNN BALKWILL, B.A. (High Honours), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, July 2015 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Empresses, Bhikṣuṇīs, and Women of Pure Faith: Buddhism and the Politics of Patronage in the Northern Wei AUTHOR: Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, B.A. (High Honours) (University of Regina), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 410. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the contributions that women made to the early development of Chinese Buddhism during the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏 (386–534 CE). Working with the premise that Buddhism was patronized as a necessary, secondary arm of government during the Northern Wei, the argument put forth in this dissertation is that women were uniquely situated to play central roles in the development, expansion, and policing of this particular form of state-sponsored Buddhism due to their already high status as a religious elite in Northern Wei society. Furthermore, in acting as representatives and arbiters of this state-sponsored Buddhism, women of the Northern Wei not only significantly contributed to the spread of Buddhism throughout East Asia, but also, in so doing, they themselves gained increased social mobility and enhanced social status through their affiliation with the new, foreign, and wildly popular Buddhist tradition.