A Brief Account of Bensen Ülger and Ülgeren Bense

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ballad of Mulan Report and Poem

Wolfe !1 Brady Wolfe Dr. Christensen CHIN 343 December 8, 2015 Mulan China to me for many years was defined by the classic story of Mulan. It was a foreign land as far away from me as anything I could fathom, yet it was so fascinating to me that I would of- ten even pretend I could speak Chinese, and I still remember the excitement I felt when as a young child I first watched Disney’s retelling of Mulan. I watched it over and over again, and when I went to China for the first time, I was honestly quite surprised to find that today’s China was quite different from my childhood imaginations inspired by that movie. For this reason, when I discovered that the legend of Mulan originates from an ancient Chinese poem, I decided it would be appropriate and enjoyable for me to choose this poem as the subject of my translation and research project. The core of this project is my own translation of the classic poem, and addi- tionally I will discuss a little bit about the history of the poem, and analyze its structure and for- mat. The original source for the poem of Mulan has been lost, but it was transcribed into the Music Bureau Collections, an anthology by Guo Maoqing put together sometime during the Song dy- nasty around the 11th or 12th century A.D., and a note is given by Guo saying that the source from which it was taken and transcribed into the collection was a compilation made during the beginning of the Tang dynasty, more or less 6th century A.D., called the Musical Records of Old and New, (Project Gutenberg). -

Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis

arts Article Cultural “Authenticity” as a Conflict-Ridden Hypotext: Mulan (1998), Mulan Joins the Army (1939), and a Millennium-Long Intertextual Metamorphosis Zhuoyi Wang Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures, Hamilton College, Clinton, NY 13323, USA; [email protected] Received: 6 June 2020; Accepted: 7 July 2020; Published: 10 July 2020 Abstract: Disney’s Mulan (1998) has generated much scholarly interest in comparing the film with its hypotext: the Chinese legend of Mulan. While this comparison has produced meaningful criticism of the Orientalism inherent in Disney’s cultural appropriation, it often ironically perpetuates the Orientalist paradigm by reducing the legend into a unified, static entity of the “authentic” Chinese “original”. This paper argues that the Chinese hypotext is an accumulation of dramatically conflicting representations of Mulan with no clear point of origin. It analyzes the Republican-era film adaptation Mulan Joins the Army (1939) as a cultural palimpsest revealing attributes associated with different stages of the legendary figure’s millennium-long intertextual metamorphosis, including a possibly nomadic woman warrior outside China proper, a Confucian role model of loyalty and filial piety, a Sinitic deity in the Sino-Barbarian dichotomy, a focus of male sexual fantasy, a Neo-Confucian exemplar of chastity, and modern models for women established for antagonistic political agendas. Similar to the previous layers of adaptation constituting the hypotext, Disney’s Mulan is simply another hypertext continuing Mulan’s metamorphosis, and it by no means contains the most dramatic intertextual change. Productive criticism of Orientalist cultural appropriations, therefore, should move beyond the dichotomy of the static East versus the change-making West, taking full account of the immense hybridity and fluidity pulsing beneath the fallacy of a monolithic cultural “authenticity”. -

The Real Story of Mulan By: the Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011

The Real Story of Mulan By: The Scribe on Friday, June 17, 2011 Many people have seen the Disney movie Mulan and do not realize that it is actually telling the story of an ancient Chinese poem titled the Ballad of Mulan. Because it is a legend, it is unknown when Mulan may have lived although she was believed to have lived during theNorthern Wei dynasty which lasted from 386CE to 534CE. In the movie, Mulan is depicted as being unskilled with weapons. The “real” Mulan, on the other hand, was said to have practiced with many different weapons. The area in which she was believed to have lived was known for practicing martial arts such as Kung Fu and for being skilled with the sword. In the legend, the real Mulan (whose name was actually Hua Mulan) rode horses and shooting arrows. In the movie as well as in the poem, there was no male child. This caused problems when the Emperor (or Khan as he is called in the poem) began to call up troops to fight the invading Mongol and nomadic tribes. If there had been a son he could have gone in his father’s place as it was only up to the family to provide one man to fight. Whether it was the father or the son did not matter; all they needed to do was provide one person to join the army. As in the Disney movie, Mulan chose to enlist in her father’s place as he was too old to fight. At the age of eighteen she joined the army and prepared to fight against the Mongolian and nomadic tribes that wanted to invade China. -

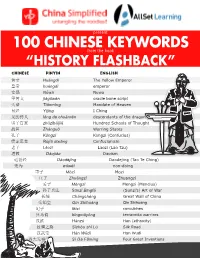

100 Chinese Keywords

present 100 CHINESE KEYWORDS from the book “HISTORY FLASHBACK” Chinese Pinyin English 黄帝 Huángdì The Yellow Emperor 皇帝 huángdì emperor 女娲 Nǚwā Nuwa 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén oracle bone script 天命 Tiānmìng Mandate of Heaven 易经 Yìjīng I Ching 龙的传人 lóng de chuánrén descendants of the dragon 诸子百家 zhūzǐbǎijiā Hundred Schools of Thought 战国 Zhànguó Warring States 孔子 Kǒngzǐ Kongzi (Confucius) 儒家思想 Rújiā sīxiǎng Confucianism 老子 Lǎozǐ Laozi (Lao Tzu) 道教 Dàojiào Daoism 道德经 Dàodéjīng Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) 无为 wúwéi non-doing 墨子 Mòzǐ Mozi 庄子 Zhuāngzǐ Zhuangzi 孟子 Mèngzǐ Mengzi (Mencius) 孙子兵法 Sūnzǐ Bīngfǎ (Sunzi’s) Art of War 长城 Chángchéng Great Wall of China 秦始皇 Qín Shǐhuáng Qin Shihuang 妃子 fēizi concubines 兵马俑 bīngmǎyǒng terracotta warriors 汉族 Hànzú Han (ethnicity) 丝绸之路 Sīchóu zhī Lù Silk Road 汉武帝 Hàn Wǔdì Han Wudi 四大发明 Sì Dà Fāmíng Four Great Inventions Chinese Pinyin English 指南针 zhǐnánzhēn compass 火药 huǒyào gunpowder 造纸术 zàozhǐshù paper-making 印刷术 yìnshuāshù printing press 司马迁 Sīmǎ Qiān Sima Qian 史记 Shǐjì Records of the Grand Historian 太监 tàijiàn eunuch 三国 Sānguó Three Kingdoms (period) 竹林七贤 Zhúlín Qīxián Seven Bamboo Sages 花木兰 Huā Mùlán Hua Mulan 京杭大运河 Jīng-Háng Dàyùnhé Grand Canal 佛教 Fójiào Buddhism 武则天 Wǔ Zétiān Wu Zetian 四大美女 Sì Dà Měinǚ Four Great Beauties 唐诗 Tángshī Tang poetry 李白 Lǐ Bái Li Bai 杜甫 Dù Fǔ Du Fu Along the River During the Qingming 清明上河图 Qīngmíng Shàng Hé Tú Festival (painting) 科举 kējǔ imperial examination system 西藏 Xīzàng Tibet, Tibetan 书法 shūfǎ calligraphy 蒙古 Měnggǔ Mongolia, Mongolian 成吉思汗 Chéngjí Sīhán Genghis Khan 忽必烈 Hūbìliè Kublai -

The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang

_full_journalsubtitle: International Journal of Chinese Studies/Revue Internationale de Sinologie _full_abbrevjournaltitle: TPAO _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0082-5433 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 1568-5322 (online version) _full_issue: 1-2 _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien J2 voor dit article en vul alleen 0 in hierna): Manling Luo _full_alt_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, hier invullen): The Politics of Place-Making _full_is_advance_article: 0 _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 T’OUNG PAO The Politics of Place-Making T’oung Pao 105 (2019) 43-75 www.brill.com/tpao 43 The Politics of Place-Making in the Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang Manling Luo Indiana University The Luoyang qielan ji 洛陽伽藍記 (Records of Buddhist Monasteries in Luoyang; hereafter Records), compiled by Yang Xuanzhi 楊衒之 (fl. 547) in roughly 547 CE, commemorates the ruined capital city of the North- ern Wei dynasty 北魏 (386-534).1 One of the few major works to survive from the period, the Records has received much critical attention, with topics ranging from its textual history to its historical and literary value. This essay focuses on what I call the “politics of place-making” in the memoir, that is, engagements with Luoyang’s space as expressions of power before and after the city’s abandonment, as represented and un- derstood by Yang. These ignored aspects shed light on the central con- cerns that motivated his writing, thereby revealing his perspective on the intersections of place, power, and human agency. The analysis al- lows us to better understand his innovations in pioneering an unofficial, space-centered historiography that defines historical agents as place- makers whose deeds and lives are anchored spatially as much as tempo- rally. -

Empresses, Bhikṣuṇῑs, and Women of Pure Faith

EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH EMPRESSES, BHIKṢUṆῙS, AND WOMEN OF PURE FAITH: BUDDHISM AND THE POLITICS OF PATRONAGE IN THE NORTHERN WEI By STEPHANIE LYNN BALKWILL, B.A. (High Honours), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © by Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, July 2015 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2015) Hamilton, Ontario (Religious Studies) TITLE: Empresses, Bhikṣuṇīs, and Women of Pure Faith: Buddhism and the Politics of Patronage in the Northern Wei AUTHOR: Stephanie Lynn Balkwill, B.A. (High Honours) (University of Regina), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. James Benn NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 410. ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the contributions that women made to the early development of Chinese Buddhism during the Northern Wei Dynasty 北魏 (386–534 CE). Working with the premise that Buddhism was patronized as a necessary, secondary arm of government during the Northern Wei, the argument put forth in this dissertation is that women were uniquely situated to play central roles in the development, expansion, and policing of this particular form of state-sponsored Buddhism due to their already high status as a religious elite in Northern Wei society. Furthermore, in acting as representatives and arbiters of this state-sponsored Buddhism, women of the Northern Wei not only significantly contributed to the spread of Buddhism throughout East Asia, but also, in so doing, they themselves gained increased social mobility and enhanced social status through their affiliation with the new, foreign, and wildly popular Buddhist tradition. -

Koguryŏ's Puyŏ-Sŏng

Appendix B Koguryŏ’s Puyŏ-sŏng urviving written sources do not state precisely when Koguryŏ occupied the Puyŏ core Sregion, but this most likely occurred shortly after 346 and certainly before about 390. Records describing events of later centuries reveal the presence of a Koguryŏ fortress called Puyŏ-sŏng, which is usually understood to indicate a Koguryŏ fortification in the old Puyŏ core region. Such a fortress may have been constructed in the early years of the Koguryŏ occupation of the area, but surviving records do not indicate its existence prior to the end of the sixth century. The earliest mention of Puyŏ-sŏng is in fact to be found in the records concerning Koguryŏ’s reoccupation of the Puyŏ territory and the expul- sion of Tudiji and his followers, and it is possible that such a fortress was not built until this time. It is also possible that the term “Puyŏ-sŏng” more broadly indicated the forti- fied lands around and including the ruins of the old Puyŏ capital, but this will not be assumed in the present study. In this appendix I will outline and evaluate current promi- nent hypotheses regarding Koguryŏ’s Puyŏ-sŏng and will propose that Longtanshan in Jilin is by far the most likely site for this northernmost of Koguryŏ fortifications.1 Sources Records describing three specific events are all that survive to provide clues to the loca- tion of Puyŏ-sŏng. The first, as noted above, concerns Koguryŏ’s expulsion of certain Sumo Mohe groups from the Puyŏ region. The original text was included in the now-lost Beifan fengsu ji, portions of which are cited in various other works, including the Taiping huanyu ji. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future. -

A Study on the Geographical Environment of the Battle of Da Fei Chuan

2020 International Conference on Social Science, Education and Management (ICSSEM 2020) A Study on the Geographical Environment of the Battle of Da Fei Chuan Li Wenping1, Yan Liang2 1College of History and Culture, Northwest Minzu University, Lanzhou, Gansu Province,730030; 2Doctor/Associate Professor of Tibet University, Lhasa, Tibet, 852000 Keywords: Da Fei Chuan; Historical geography; Plateau diseases; Influence Abstract: By using historical documents, this paper probes into the influence of geographical environment factors on the war process during the war of Da Fei Chuan between Tang and Tubo. It is believed that diseases caused by geographical environment limit the expansion of living space for both Tang and Tubo. Plateau diseases and tactical errors are one of the main reasons for Tang army's failure, and also an important reason for Tang army's being trapped in Qinghai and unable to go further. Through the modern medical concept, the cold disease and altitude reaction are re-analyzed, and the place where Da Fei Chuan War took place is verified, so as to determine the actual influence of geographical environment problems and the constraints of altitude environment on both Tang and Tubo. Throughout the history of world civilization, diseases and environment change the development trend of human society, which is not a special case of a certain place. Such natural environmental factors include diseases caused by internal geographical environment, thus restricting the flow and migration of foreign population. There is also reverse transmission of epidemic diseases caused by the movement and migration of foreign population. However, whether it is positive restriction caused by natural environmental factors or reverse destruction, it is an important factor that cannot be ignored in observing the rise and fall of human civilization. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5033

Chapter 6 Tang and Korea: Expansion and Withdrawal While the Turks, as the dominant contemporary nomad power in Mongolia, were inescapably a major concern in Chinese foreign relations until the mid-eighth century, Chinese rulers from Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty to Gaozong of the Tang dynasty were also obsessed with the con quest of Koguryo. They launched massive and costly military expeditions against Koguryo on a scale unprecedented in previous Sino-Korean rela tions. The wars with Koguryo are a prime example of the use of aggres sive force as an instrument of Chinese foreign policy. Although ultimately successful tmder Tang Gaozong in the sense that Koguryo was destroyed, the wars were of questionable long-term benefit to China and instead in advertently contributed to the rise of a unified Korean state which deferred to but was essentially independent of China. As previous scholars have shown, there were pragmatic as well as ideological reasons for the continued interest of the early Tang rulers in Korea. Pulleyblank holds that the presence of strong separatist sentiments in the Hebei region made the Tang court at Chang’an feel threatened by the possibility of close relations between Hebei and its neighbor, Kogu- ryo.^ Somers considers Tang Taizong’s campaigns into the border regions of the Northeast as a necessary step for the extension of imperial rule into the North China Plain and as an important coercive measure for the full consolidation of dynastic power.^ Wechsler concludes that Tang feared that Koguryo would unify the whole Korean peninsula, and so it wanted to keep Korea divided and prevent its alliance with other non-Chinese in eastern Manchuria and in Japan. -

Proquest Dissertations

TO ENTERTAIN AND RENEW: OPERAS, PUPPET PLAYS AND RITUAL IN SOUTH CHINA by Tuen Wai Mary Yeung Hons Dip, Lingnan University, H.K., 1990 M.A., The University of Lancaster, U.K.,1993 M.A., The University of British Columbia, Canada, 1999 A THESIS SUBIMTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Asian Studies) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September 2007 @ Tuen Wai Mary Yeung, 2007 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-31964-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these.