Berlin District Centres of Adult Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Die Heidekrautbahn: Über Wilhelmsruh Nach Gesundbrunnen Ursprünglicher Ausgangspunkt Der Heide- Krautbahn War Der Bahnhof Wilhelmsruh

FAKTEN ZUR REAKTIVIERUNG DER STAMMSTRECKE DIE HEIDEKRAUTBAHN: ÜBER WILHELMSRUH NACH GESUNDBRUNNEN URSPRÜNGLICHER AUSGANGSPUNKT DER HEIDE- KRAUTBAHN WAR DER BAHNHOF WILHELMSRUH. ES BESTEHEN ÜBERLEGUNGEN, DIE URSPRÜNGLICHE VERBINDUNG WIEDER AUFZUNEHMEN. EINFÜHRUNG Die Niederbarnimer Eisenbahn-AG (NEB) betreibt nördlich von Berlin die Infra - struktur für die Regionalbahnlinie RB27 Berlin-Karow/Berlin Gesundbrunnen – Basdorf – Groß Schönebeck/Schmachtenhagen. In der Öffentlich keit ist die allgemeine Bezeichnung für diese Strecke Heidekrautbahn. Historischer Ausgangspunkt der Heidekrautbahn in Berlin war der Bahnhof Wilhelmsruh, an der Grenze zwischen den Bezirken Reinickendorf und Pankow. Die Strecke – in Betrieb genommen 1901 – führt in nördlicher bzw. nordöst- licher Richtung über Berlin-Blankenfelde, Schildow, Mühlenbeck und Schön- walde nach Basdorf, wo sie sich verzweigt. Mit dem Bau der Berliner Mauer wurde der Bahnhof Wilhelmsruh geschlossen und die Strecke in diesem Bereich abgebaut. In Schönwalde stellt bis heute eine 1950 gebaute Verbindungsstrecke den Anschluss an die S-Bahn in Berlin- Karow her. Seit vielen Jahren ist es politisches Ziel, die ursprüngliche Verbindung Richtung Berlin-Wilhelmsruh für den Personenverkehr wieder aufzunehmen. Hierzu wurde in den letzten Jahren eine umfangreiche grundlegende theoretische, „DIE WACHSENDE REGION BRAUCHT DRINGEND konzeptionelle und planerische Vorarbeit geleistet. Die Wiederinbetrieb- ATTRAKTIVERE ÖPNV-VERBINDUNG NACH BERLIN. nahme der Verbindung nach Berlin-Wilhelms ruh erfolgt mit dem -

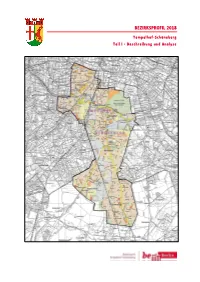

Bezirksprofil Tempelhof-Schöneberg (07)

BEZIRKSPROFIL 2018 Tempelhof-Schöneberg Teil I - Beschreibung und Analyse Impressum Herausgebend: Bezirksamt Tempelhof-Schöneberg von Berlin Koordination: Ulrich Binner (SPK DK), Tel.: (030) 90277-6651 Bildnachweis: SPK DK oder wie angegeben Bearbeitungsstand: beschlossen durch AG SRO am 18.08.2018 beschlossen durch Bezirksamt Tempelhof-Schöneberg am 18.12.2018 Datenstand: KID & DGZ 12/2016, ergänzende Daten wie angegeben Inhaltsverzeichnis 0 Vorbemerkungen .......................................................................................................... 1 0.1 Aufbau und Gliederung .................................................................................................................................... 1 0.2 Ergänzungen und erweiterte Auswertungen ................................................................................................. 2 1 Portrait des Bezirks und seiner Bezirksregionen .............................................................. 3 1.1 Schöneberg Nord (070101) .............................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Schöneberg Süd (070202) ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.3 Friedenau (070303) .......................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Tempelhof (070404) ..................................................................................................................................... -

Intensivversorgung Tracheotomierter Patienten Mit Und Ohne Beatmung – Bedarfsgerechtigkeit Regionaler Angebote

Intensivversorgung tracheotomierter Patienten mit und ohne Beatmung – Bedarfsgerechtigkeit regionaler Angebote Susanne Stark, Yvonne Lehmann, Michael Ewers Working Paper No. 19-01 Berlin, April 2019 Institut für Gesundheits- und Pflegewissenschaft Zitierhinweis: Stark S, Lehmann Y, Ewers M (2019): Intensivversorgung tracheotomierter Patienten mit und ohne Beatmung – Bedarfsgerechtigkeit regionaler Angebote Working Paper No. 19-01 der Unit Gesundheitswissenschaften und ihre Didaktik. Berlin: Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin Impressum: Working Paper No. 19-01 der Unit Gesundheitswissenschaften und ihre Didaktik Berlin, April 2019 ISSN 2193-0902 Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin Institut für Gesundheits- und Pflegewissenschaft CVK – Augustenburger Platz 1 13353 Berlin | Deutschland Tel. +49 (0)30 450 529 092 Fax +49 (0)30 450 529 900 http://igpw.charite.de Intensivversorgung tracheotomierter Patienten mit und ohne Beatmung Abstract Tracheotomierte Patienten mit und ohne Beatmung benötigen aufgrund ihrer komplexen Prob- lem- und Bedarfslagen häufig eine multiprofessionelle, auf Integration und Kontinuität ange- legte Intensivversorgung. Diese geht mit hohen Anforderungen an die fachliche Expertise, Ko- ordination und Kooperation der beteiligten Sektoren, Organisationen und Professionen einher. Vorliegenden Erkenntnissen zufolge werden diese hohen Anforderungen noch selten erfüllt. Patienten und Angehörige, aber auch Versorgungskoordinatoren und Fallmanager haben oft- mals erhebliche Probleme, bedarfsgerechte Versorgungsangebote ausfindig -

Blankenfelde-Mahlow En Tdecken, Erleben, G Estalten Willkommen in Blankenfelde-Mahlow, Willkommen Im Musikerviertel!

Blankenfelde-Mahlow entdecken, erleben, g estalten Willkommen in Blankenfelde-Mahlow, willkommen im Musikerviertel! Hier hat Ihre Zukunft ein Zuhause Das Musikerviertel in Mahlow-West ist eines der größten Baugebiete im südlichen Umland der Hauptstadt – nur wenige Kilometer von der Stadtgrenze Berlins entfernt, in einer der attraktivsten, charmantesten und infrastrukturell hervorragend angebundenen Gemeinden des Landkreises Teltow-Fläming. Sie sind herzlich willkommen – ob als Investor, als Anleger oder als privater Eigenheimbauer. Alle Grundstücke sind bauträgerfrei, komplett erschlossen und freuen sich auf ihre neuen Besitzer und Bauherren. Informieren Sie sich, schauen Sie sich bei uns um! Sie werden begeistert sein – vom Land, von den Leuten und von einer erstklassigen Lage! www.musikerviertel.com Interview mit dem Bürgermeister Welche städtebaulichen Projekte werden jetzt und in naher Zukunft in Blankenfelde-Mahlow realisiert? Nachdem wir in den vergangenen Jahren unsere sozialen Einrich- tungen entsprechend dem gewachsenen Bedarf modernisiert, erweitert und teilweise neu gebaut haben, möchten wir nun gerne in den kommenden Jahren den Bebauungsplan „Zentrum Blankenfelde“ umsetzen. Dessen Herzstück ist die Errichtung eines neuen Rathauses, das den gestiegenen Erfordernissen unserer großen Gemeinde gerecht wird. Unsere Wohnungsverwaltungs- und Baugesellschaft Blanken- felde mbH, WOBAB, befi ndet sich gegenwärtig in der Bau- planungs phase für ein Objekt „Betreutes Wohnen“. Im Norden und im Süden unserer Gemeinde möchten wir zwei neue Wohn- gebiete für mehrere Tausend neue Bürger entwickeln. Außerdem soll das noch der Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben gehö- Bürgermeister Ortwin Baier rende Gelände der ehemaligen Blankenfelder Kaserne renaturiert und teilweise mit Einfamilienhäusern bebaut werden. Blankenfelde-Mahlow entdecken, erleben, gestalten – Werden in Blankenfelde-Mahlow weiterhin was bedeutet dieses Motto für Sie? neue Arbeitsplätze geschaff en? Wir sind eine sehr lebendige Gemeinde. -

Wohnen in Berlin Und Pankow

INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung ............................................................................................................................. 4 Wohnen in Berlin und Pankow ........................................................................................... 5 Mieterhöhung bei Sanierung und Modernisierung begrenzen, Verdrängung verhindern! ... 5 Masterplan „Attraktive Mietwohnungen und Quartiere in Pankow“ ..................................... 6 Bildung im Bezirk Pankow .................................................................................................. 7 Frühkindliche Bildung und Ganztagsbetreuung für alle – Chancen für Kinder und Eltern verbessern ......................................................................................................................... 8 Schule ............................................................................................................................... 9 Kulturelle Bildung ..............................................................................................................11 Musikschule ..................................................................................................................11 Museum ........................................................................................................................11 Bibliotheken ..................................................................................................................11 Volkshochschule ...........................................................................................................12 -

I DDR-Elitens Højborg

Kristeligt Dagblad Lørdag 5. april 2014 Denne side er redigeret af Mie Petersen Rejser&Kultur | 23 I DDR-elitens højborg I det tidligere Østtyskland boede eliten i villaerne ved Majakowskiring i Berlin. Bag skarpt bevæbnede vagter og høje mure levede de adskilt fra folket AF JENS MALLING ter kontrollerede mange gan- Ved festlige lejligheder som række rykkede derefter ind i vandledes området til et me- [email protected] ge stemplede og underskrev- den 1. maj eller Østtysklands villaerne på Majakowskiring, re normalt boligkvarter. Man- ne besøgstilladelser. En høj nationaldag, den 7. oktober, herunder et stort antal Stasi- ge år efter kunne man dog Ved første øjekast synes der mur omkransede området og har de måske delt en flaske af medarbejdere. stadig støde ind i det heden- ikke at være andet at komme forhindrede adgang for kam- den udmærkede DDR-cham- DDR begyndte at slå gangne Østtysklands aller- efter i villakvarteret end ren merater, der ikke var så højt pagne Rotkäppchen – som sprækker i slutningen af mest prominente personager idyl. Det fremstår fredfyldt og oppe i samfundshierarkiet. stadig er i produktion – med 1980’erne, og den folkelige på de hyggelige villaveje. harmonisk. Russerne tog også initiativ deres hustruer. revolution, der brød ud i maj Manden, der kortvarigt hav- At dømme efter husenes til at omdøbe vejene i kvarte- 1989, markerede, at den pri- de generalsekretærposten ef- størrelse residerer her Berlins ret efter kulturpersonlighe- Det gode sammenhold var vilegerede kommunistiske ter Honecker, Egon Krenz, bedre borgerskab. Skiltene der i deres hjemland. Således dog truet. Opstande mod de livsstil i kvarteret var ved at blev tvunget ud af sit hjem på ved siden af dørklokkerne hedder de stadig Boris-Pa- kommunistiske regimer i være omme. -

Die Welt Kauft in Dieser Stadt Einwohnern Laut Zensus 2011 Die Niederlassungsleiter Berlin Des Bera- Auch Mietsteigerungen Begrenzen

52 TRENDVIERTEL TRENDVIERTEL 53 WOCHENENDE, 7./8./9. JUNI 2013, NR. 107 WOCHENENDE, 7./8./9. JUNI 2013, NR. 107 1 1 ddp images Bauwert ZB picture-alliance/ Pressebild Berlin, Fernsehturm am Alexanderplatz: Alles, was Geld hat, Die Rosengärten Im Westteil der Stadt: Teuer wohnen im Kreuzung in Prenzlauer Berg: Böse Zungen behaupten, dass im beliebten Projekt Living 108 an der Chausseestraße in Mitte: Luxus strebt in die Mitte. alten Zentrum. Wohnkiez um den Kollwitzplatz mehr Schwaben als Berliner leben. über Luxus, entwickelt von der Peach-Property-Group. BERLIN sagt Maren Kern, die Chefin des Ver- in Lichtenberg, in Karlshorst und im Um- Euro pro Quadratmeter aus – in Mün- bands BBU, dessen Mitgliedsunterneh- BERLIN IN ZAHLEN feld des Wissenschaftsparks Adlershof. chen ist er fast doppelt so hoch. Auch men 40 Prozent der Berliner Mietwoh- Allerdings will der Berliner Senat nicht seien die Kaufpreise „im Vergleich zu an- nungen verwalten. Auch André Adami, Berlin ist mit knapp 3,3 Millionen nur den Wohnungsbau fördern, sondern deren Hauptstädten sehr günstig“, sagt Die Welt kauft in dieser Stadt Einwohnern laut Zensus 2011 die Niederlassungsleiter Berlin des Bera- auch Mietsteigerungen begrenzen. So Thomas Zabel vom Maklerunternehmen tungsunternehmens Bulwien Gesa, rät, größte deutsche Stadt. 2011 und hat er sofort von der neuen gesetzlichen Berlin Capital Investments. sich nicht auf das Stadtzentrum zu be- 2012 gewann die Stadt jeweils Möglichkeit Gebrauch gemacht, den Im Übrigen, berichtet Zabel, sei je- Berlin zieht viele internationale Investoren an. Dadurch sind schränken: „Alle Lagen, die nicht weiter rund 40 000 Einwohner hinzu. Bis Mieterhöhungsspielraum innerhalb von der ausländische Kaufinteressent, als 500 Meter von einem S- oder U-Bahn- zum Jahr 2030 erwarten die drei Jahren auf 15 Prozent zu deckeln. -

Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany Douglas Selvage / Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records

Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany Douglas Selvage / Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records In Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany, historian Keith R. Allen analyzes the “overlooked story of refugee screening in West Germany” (p. xv). Building upon his previous German-language study focused on such screening at the Marienfelde Refugee Center in West Berlin (Befragung - Überprüfung - Kontrolle: die Aufnahme von DDR- Flüchtlingen in West-Berlin bis 1961, Berlin: Ch. Links, 2013), Allen examines the places, personalities, and practices of refugee screening by the three Western Powers, as well as the German federal government, in West Berlin and throughout West Germany. The topic is particularly timely since, as Allen notes, many of “the screening programs established during the darkest days of the Cold War” (p. xv) continue today, although their targets have shifted. The current political debates about foreign and domestic intelligence activities in Germany, including the issue of refugee screening, echo earlier disputes from the years of the Bonn Republic. The central questions remain: To what extent have citizenship rights and the Federal Republic’s sovereignty been compromised by foreign and domestic intelligence agencies – largely with the consent of the German government – in the name of security? BERLINER KOLLEG KALTER KRIEG | BERLIN CENTER FOR COLD WAR STUDIES 2017 Douglas Selvage Interrogation Nation Allen divides his study into three parts. In Part I, he focuses on “places” – the various sites in occupied West Berlin and western Germany where refugees were interrogated. He sifts through the alphabet soup of acronyms of US, British, French, and eventually West German civilian and military intelligence services and deciphers the cover names of the institutions and locations at which they engaged in screening activities during the Cold War and beyond. -

Netzelement N 1 Der Verkehrslösung Heinersdorf & Kita Hödurstraße Im

Planungsstudie Netzelement N 1 der Verkehrslösung Heinersdorf & Kita Hödurstraße im Ortskern Heinersdorf Auszüge unserer Recherche Verkehrslösung Heinersdorf Hintergrund und Stand der Dinge Kita-Grundstück Ende 2015 haben wir in der Hödurstraße 8, 10 ein 3.000 qm großes Grundstück erworben. Darauf soll ein Kita-Neubau mit 150 Betreuungs- N4 plätzen entstehen, der in der Bezirksregion (Kategorie 1 im Kita-Bedarfsatlas der Senatsverwaltung) dringend benötigt und von Seiten des Bezirksjugendamtes befürwortet wird. Gewerbegebiet Vorbereitende Untersuchung, Verkehrslösung und Rahmenplanung Heinersdorf Mit dem Bau der Kita kann noch nicht begonnen werden, solange erforderliche planungsrechtliche Klärungen wie nachstehend noch offen N1 Heinersdorf sind. Das Grundstück liegt im Geltungsbereich eines Bebauungsplans im Aufstellungsbeschluss (B-Plan XVIII-32 (WA, MI GRÜN, SPIEL, SCHU- LE, JUGEND, VERKEHR). Weiterhin liegt es im Untersuchungsgebiet der ´Vorbereitenden Untersuchung´ zum Wohngebiet `Blankenburger Quelle: www.Zukunftswerkstatt Heinersdorf.de N2 Pflasterweg´ sowie im Kerngebiet der aktuell in Arbeit befindlichen ´Rahmenplanung Heinersdorf´. Neben konkreten Planungsinhalten für den Bebauungsplan ist hierbei zunächst die übergeordnete Verkehrsführung (Straßennetz und ÖPNV) ausschlaggebend- unser Grundstück Heinersdorf ist hiervon unmittelbar betroffen (siehe dazu „Verkehrslösung Heinersorf“). Bevor es mit konkreten Maßnahmen im Ortskern losgehen kann, sind die Ergebnisse der Untersuchung abzuwarten. Ungeachtet dessen ist eine Bebauung des Grundstücks nach § 34 BauGB derzeit in Prü- N3 fung. Alte Gärtnerei/ eigene Planungsstudien zum Ortskern/ Netzelement N1 Kartengrundlage: Karte von Berlin 1:5.000 (K5) Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen / Abteilung III Vor zwei Jahren haben wir begonnen, im Dialog mit Bezirk und Senat in Verhandlungen mit dem einstmalig verkaufswilligen Eigentümer Verkehrslösung Heinersdorf. Quelle: www SenStadt/ Verkehrslösung Heinersdorf des Grundstücks „Alte Gärtnerei“ (unserem Nachbargrundstück) zu treten. -

Bus Linie X83 Fahrpläne & Netzkarten

Bus Linie X83 Fahrpläne & Netzkarten X83 Königin-Luise-Str./Clayallee ◄ ► Nahariyastr. Im Website-Modus Anzeigen Die Bus Linie X83 (Königin-Luise-Str./Clayallee ◄ ► Nahariyastr.) hat 3 Routen (1) Königin-Luise-Str./clayallee: 00:03 - 23:43 (2) Lichtenrade, Nahariyastr.: 00:06 - 23:46 Verwende Moovit, um die nächste Station der Bus Linie X83 zu ƒnden und, um zu erfahren wann die nächste Bus Linie X83 kommt. Richtung: Königin-Luise-Str./Clayallee Bus Linie X83 Fahrpläne 33 Haltestellen Abfahrzeiten in Richtung Königin-Luise-Str./clayallee LINIENPLAN ANZEIGEN Montag 00:03 - 23:43 Dienstag 00:03 - 23:43 Nahariyastr. Nahariyastraße, Berlin Mittwoch 00:03 - 23:43 Nahariyastr. Donnerstag 00:03 - 23:43 Nahariyastraße, Berlin Freitag 00:03 - 23:43 Skarbinastr. Samstag 00:03 - 23:43 Nahariyastraße 19, Berlin Sonntag 00:03 - 23:43 Rennsteig Groß-Ziethener Straße 83, Berlin Taunusstraße Groß-Ziethener Straße 71, Berlin Bus Linie X83 Info Richtung: Königin-Luise-Str./Clayallee Im Domstift/Groß-Ziethener Str. Stationen: 33 Groß-Ziethener Straße 44, Berlin Fahrtdauer: 45 Min Linien Informationen: Nahariyastr., Nahariyastr., Lichtenrader Damm/Barnetstr. Skarbinastr., Rennsteig, Taunusstraße, Im Lichtenrader Damm/Barnetstraße, Berlin Domstift/Groß-Ziethener Str., Lichtenrader Damm/Barnetstr., Barnetstr./Steinstr., Simpsonweg, Barnetstr./Steinstr. S Schichauweg, Egestorffstraße, Sperenberger Str., Barnetstraße/Steinstraße, Berlin Nunsdorfer Ring Süd, Nunsdorfer Ring Nord, Nahmitzer Damm/Motzener Str., Nahmitzer Simpsonweg Damm/Marienfelder Allee, Friedenfelser Str., Vom Simpsonweg, Berlin Guten Hirten, Friedrichrodaer Str., Marchandstr., Emmichstr., Am Gemeindepark, Lankwitz Kirche, S S Schichauweg Lankwitz, Steglitzer Damm/Bismarckstr., S+U Schichauweg 1, Berlin Rathaus Steglitz [Albrechtstr.], Grunewaldstr./Lepsiusstr., Schmidt-Ott-Str., Königin- Egestorffstraße Luise-Platz/Botanischer Garten, Arnimallee, Edwin- Egestorffstraße, Berlin Redslob-Str., U Dahlem-Dorf, U Dahlem-Dorf Sperenberger Str. -

Mitte Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Pankow

► Vorwort 5 Mitte 1 Das »himmelbeet« in Wedding 6 2 Einkäufen im Mini-Kaufhaus in Wedding 8 3 Smart Eating in der Data Kitchen 10 4 Bibliothek am Luisenbad 12 5 Gleim-Oase: die grüne Insel im Wedding 14 6 Leckere Burger in ausgefallener Location 16 7 Franzose mit witzigem Menü-Konzept 18 8 Cocktail trinken in einer versteckten Bar 20 9 Katz Orange: Restaurant in alter Brauerei 22 10 Staunen in der Wunderkammer Olbricht 24 11 Die Dachterrasse des Hotel AMANO 26 12 Brötchen holen in Sarah Wieners Bio-Bäckerei 26 13 Cowshed Spa im Soho House 28 14 Tadshikische Teestube: märchenhaft Tee genießen 30 15 Kennedy Museum: in der Jüdischen Mädchenschule 32 16 Beeindruckende Boros Collection 34 17 Entspannen über den Dächern der Stadt 36 18 Alter Grenzturm am Potsdamer Platz 36 19 Ein Tag Luxus, bitte! 38 Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg 20 Sonnenuntergang auf der Modersohnbrücke 40 21 Das beliebteste Outlet der Stadt 42 22 Minigolf bei Schwarzlicht 44 23 Street Food Thursday 46 24 Panoramablick über Kreuzberg 46 25 Akupunktur, die sich jeder leisten kann 47 26 Ein Besuch im Pfefferhaus 48 27 Die kleinste Disko der Welt 50 28 Crazy Hot Dogs 50 29 Kalifornien zum Schlecken 52 Pankow 30 Erinnerungen in der Alten Bäckerei Pankow 54 31 Die Ruine des Kinderkrankenhauses in Weißensee 56 32 Lustige Tischtennis-Bar im Prenzlauer Berg 56 33 Türkische Küche - modern interpretiert 58 34 Stulle essen bei Suicide Sue 60 35 Onkel Philipp's Spielzeugwerkstatt 62 36 Verwunschene Oase auf dem Friedhof 64 37 Zur Ruhe kommen im Stadtkloster Segen 66 38 Entspannen im Ruhepool -

In the Name of My Father

Page 1 of 6 From DIE ZEIT, a German nationwide weekly newspaper, January 15, 2009 Looted art In the name of my father Hans Sachs, a Jewish dentist, owned the world’s most important collection of posters. It was looted by the Nazis and locked up by East Germans. The son is now intent on recovering this treasure from the state by Kerstin Kohlenberg It smells of linoleum and harsh cleaners. The steps echo against the thick walls. Cold neon lights the floor. Behind five identical doors lies the treasure, now at the center of an all-out dispute. A security key is gotten. A door opens onto 24 closed grey metal drawer cabinets. They contain heavy folders with 100-year old posters, interleaved with acid- absorbing paper. The posters promote films, exhibitions, consumer products – they are a piece of German history reflected in the graphic arts of advertising. A collection that with its 12,500 posters was once the largest in the world and whose 4,000 remaining posters are estimated to have a value of several million euros. It is the collection of Hans Sachs, a Jewish dentist, who brought this assortment together in the years between 1896 and 1938 when it was confiscated by the Nazis. After the war the posters were long considered lost but then turned up in an East Berlin basement and now have been housed for some time in the former Friedrich-Engels barracks in Berlin- Mitte, the poster storage facility for the Deutsche Historische Museum (German Historical Museum). The climate control equipment on the cabinets is ticking softly, but the tranquility is deceptive.