Interrogation Nation: Refugees and Spies in Cold War Germany Douglas Selvage / Office of the Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation

Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1993 In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation Janet Ainsworth Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Janet Ainsworth, In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation, 103 YALE L.J. 259 (1993). https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles In a Different Register: The Pragmatics of Powerlessness in Police Interrogation Janet E. Ainswortht CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 260 II. How WE Do THINGS WITH WORDS .............................. 264 A. Performative Speech Acts ................................. 264 B. Indirect Speech Acts as Performatives ......................... 267 C. ConversationalImplicature Modifying Literal Meaning ............. 268 H. GENDER AND LANGUAGE USAGE: A DIFFERENT REGISTER .............. 271 A. Characteristicsof the Female Register ........................ 275 1. Hedges ........................................... 276 2. Tag Questions ...................................... 277 t Associate Professor of Law, University of Puget Sound School of Law. B.A. Brandeis University, M.A. Yale University, J.D. Harvard Law School. My appreciative thanks go to Harriet Capron and Blain Johnson for their able research assistance. I am also indebted to Melinda Branscomb, Jacqueline Charlesworth, Annette Clark, Sid DeLong, Carol Eastman, Joel Handler, Robin Lakoff, Debbie Maranville, Chris Rideout, Kellye Testy, Austin Sarat, and David Skover for their helpful comments and suggestions. -

Project: Natural and Artificial Systems for Recharge and Infiltration (NASRI)

Project: Natural and Artificial Systems for Recharge and Infiltration (NASRI) Induced by well abstraction, surface water infiltrates into Berlin aquifers and is used for drinking water production. The advantage of bank filtration is the capability of the subsurface to remove contaminants. Because a large proportion of the surface water in Berlin originates from treated effluents, the system is a semi-closed water cycle relying partly on indirect wastewater reuse. Processes accompanying bank filtration and artificial recharge are currently studied in Berlin within a multidisciplinary project initiated by the KWB (Kompetenzzentrum Wasser Berlin) as a cooperation of the Berlin Water Works (BWB), the Technical and the Free University of Berlin, the German Environmental Protection Agency (UBA) and the Institute of Ecohydrology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) named Nasri (Natural and Artificial Systems for Recharge and Infiltration). It focuses on the behaviour and removal of, for example, pathogens, microsystens, organic pollutants as well as pharmaceutically active compounds during underground passage. Within NASRI, the Free University evaluates the hydrogeology, hydraulics, geochemistry and hydrochemistry of the field sites. Wastewater indicators (e.g. Cl-, B, EDTA, Gd-EDPA), stable isotopes (18O, 2H) and Tritium/Helium age dating are used to calculate travel times to drinking water wells and proportions of bank filtrate in individual wells. The tracer results serve as a basis for the interpretation of the fate and behaviour of potential contaminants (e.g. drug residues or organic pollutants) analysed by project partners. http://www.kompetenzwasser.de/Natural-and-Artificial-Systems-for.23.0.html?&L=1 Project: Evaluation of transport processes in the Oderbruch aquifer using the tritium/helium age dating method Detailed groundwater monitoring was carried out within a previous research project in an anoxic, river recharged, pleistocene aquifer in the Oderbruch polder in Germany. -

Ten Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center Conveys MITRE’S Expertise on Accumulated Expertise on Enterprise-Grade Computer Network Defense

Bleed rule--remove from file Bleed rule--remove from file MITRE’s accumulated Ten Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations Center conveys MITRE’s expertise on accumulated expertise on enterprise-grade computer network defense. It covers ten key qualities enterprise- grade of leading Cybersecurity Operations Centers (CSOCs), ranging from their structure and organization, computer MITRE network to processes that best enable effective and efficient operations, to approaches that extract maximum defense Ten Strategies of a World-Class value from CSOC technology investments. This book offers perspective and context for key decision Cybersecurity Operations Center points in structuring a CSOC and shows how to: • Find the right size and structure for the CSOC team Cybersecurity Operations Center a World-Class of Strategies Ten The MITRE Corporation is • Achieve effective placement within a larger organization that a not-for-profit organization enables CSOC operations that operates federally funded • Attract, retain, and grow the right staff and skills research and development • Prepare the CSOC team, technologies, and processes for agile, centers (FFRDCs). FFRDCs threat-based response are unique organizations that • Architect for large-scale data collection and analysis with a assist the U.S. government with limited budget scientific research and analysis, • Prioritize sensor placement and data feed choices across development and acquisition, enteprise systems, enclaves, networks, and perimeters and systems engineering and integration. We’re proud to have If you manage, work in, or are standing up a CSOC, this book is for you. served the public interest for It is also available on MITRE’s website, www.mitre.org. more than 50 years. -

Tradecraft Primer: a Framework for Aspiring Interrogators

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 9 Number 4 Volume 9, No. 4, Special Issue Winter 2016: Understanding and Article 11 Resolving Complex Strategic Security Issues Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. Mark J. Roberts Subject Matter Expert Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 139-141 Recommended Citation Roberts, Mark J.. "Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016.." Journal of Strategic Security 9, no. 4 (2016) : 139-141. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.9.4.1576 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol9/iss4/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol9/iss4/11 Roberts: Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Pau Tradecraft Primer: A Framework for Aspiring Interrogators. By Paul Charles Topalian. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2016. ISBN 978-1-4987-5114-8. Photographs. Figures. Sources cited. Index. Pp. xv, 140. $59.95. Interrogation is a word fraught with many inferences and implications. Revelations of waterboarding, incidents in Abu Graib and Guantanamo, and allegations of police impropriety in obtaining confessions have all cast the topic in a negative light in recent years. -

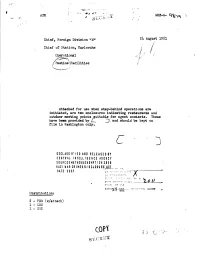

• (OP1 Si ,C1-R"T .L.A%

AIR MG —A— (A %-1 ) Chief, Foreign Division oll" 24 August 1951 . / Chief of . Station, Karlsruhe Operational. IPastime\Facilities Attached for use when star-behind operations are initiated, are two enclosures indicating restaurants and outdoor meeting points suitable for agent contacts. These have been provided by J. should be kept on file in Washington only. C DECLASS IF I ED AND RELEASED BY CENTRAL I NTELL IS ENCE AGENCY SOURCES METHOOSEX EHPT ION MO NAZI WAR CR IMES 01 SCLODURrADL.,,, DATE 20 07 • P'J! U1E104a___, t7.7 77; o Distributiont 2 - FDA (w/attach) 1 - COS 1 - BOB • (OP1 si ,C1-r"T .L.A% POINTS IN BERLIN SUITABLF, FOR OUTDOOR mtEmlis 1. Berlin-Britz Telephone booth in front of Post Office on the corner of . Chaussee Strasse and Tempelhofer Weg. 2. Berlin-Charlottenburg Streetcar stop for the line towards Charlottenburg in front Of S-Bahnhof Westend.. 3. Berlin-Friedenau Telephone booth on the corner of Handjery Strasse and Isolde Strasse (Maybach Platz). 4. Berlin-Friedrichsfelde Pillar used for posters on the corner of Schloss StrasSe and Wilhelm Strasse. 5. .Berlin=Friedrichshain Streetcar stop for line 65 in the direction of Lichtenberg located on Lenin Platz. 6. Derlin-Grffnau Final stop for bus lines A 36 and 38 in Grffnau. 7. Berlin-Gruneuald Ticket counter in S-Bahnhof Halensee. 8. Berlin-Heinersdorf Pillar used for posters on the corner of Stiftsweg and Dreite Strasse. 9. Berlin-Hermsdorf Ticket counter located inside S-Bahnhof Hermsdorf. 10. Berlin-Lankuitz Pillar used for posters on the corner of Marienfelde Strasse and Emmerich Strasse. -

Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques

Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques Anne Daugherty Miles Analyst in Intelligence and National Security Policy July 9, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43906 Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation Techniques Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Perspectives on EITs and Torture..................................................................................................... 7 Perspectives on EITs and Values .................................................................................................... 10 Perspectives on EITs and Effectiveness ......................................................................................... 11 Additional Steps ............................................................................................................................. 14 Appendixes Appendix A. CIA Standard Interrogation Techniques (SITs) ........................................................ 15 Appendix B. CIA Enhanced Interrogation Techniques (EITs) ....................................................... 17 Contacts Author Contact Information........................................................................................................... 18 Congressional Research Service Perspectives on Enhanced Interrogation -

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other Books in the Current Controversies Series

Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Other books in the Current Controversies series: The Abortion Controversy Issues in Adoption Alcoholism Marriage and Divorce Assisted Suicide Medical Ethics Biodiversity Mental Health Capital Punishment The Middle East Censorship Minorities Child Abuse Nationalism and Ethnic Civil Liberties Conflict Computers and Society Native American Rights Conserving the Environment Police Brutality Crime Politicians and Ethics Developing Nations Pollution The Disabled Prisons Drug Abuse Racism Drug Legalization The Rights of Animals Drug Trafficking Sexual Harassment Ethics Sexually Transmitted Diseases Family Violence Smoking Free Speech Suicide Garbage and Waste Teen Addiction Gay Rights Teen Pregnancy and Parenting Genetic Engineering Teens and Alcohol Guns and Violence The Terrorist Attack on Hate Crimes America Homosexuality Urban Terrorism Illegal Drugs Violence Against Women Illegal Immigration Violence in the Media The Information Age Women in the Military Interventionism Youth Violence Espionage and Intelligence Gathering Louise I. Gerdes, Book Editor Daniel Leone,President Bonnie Szumski, Publisher Scott Barbour, Managing Editor Helen Cothran, Senior Editor CURRENT CONTROVERSIES San Diego • Detroit • New York • San Francisco • Cleveland New Haven, Conn. • Waterville, Maine • London • Munich © 2004 by Greenhaven Press. Greenhaven Press is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Greenhaven® and Thomson Learning™ are trademarks used herein under license. For more information, contact Greenhaven Press 27500 Drake Rd. Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 Or you can visit our Internet site at http://www.gale.com ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means—graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems—without the written permission of the publisher. -

Digital Forensics: Methods and Tools for Retrieval and Analysis of Security

NORGES TEKNISK-NATURVITENSKAPELIGE UNIVERSITET FAKULTET FOR INFORMASJONSTEKNOLOGI, MATEMATIKK OG ELEKTROTEKNIKK MASTEROPPGAVE Kandidatens navn: Andreas Grytting Furuseth Fag: Datateknikk Oppgavens tittel (norsk): Oppgavens tittel (engelsk): Digital Forensics: Methods and tools for re- trieval and analysis of security credentials and hidden data. Oppgavens tekst: The student is to study methods and tools for retrieval and analysis of security credentials and hidden data from different media (including hard disks, smart cards, and network traffic). The student will perform prac- tical experiments using forensic tools and attempt to identify possibilities for automating evidence analysis with respect to e.g. passwords, crypto- graphic keys, encrypted data, steganography, etc. The student will also study the correlation of identified security credentials from different media in order to improve the possibility of successful identification and decryp- tion of encrypted data. Oppgaven gitt: 28. Januar 2005 Besvarelsen leveres innen: 1. August 2005 Besvarelsen levert: 15. Juli 2005 Utført ved: Institutt for datateknikk og informasjonsvitenskap Q2S - Centre for Quantifiable Quality of Service in Communication Systems Veileder: Andr´e Arnes˚ Trondheim, 15. Juli 2005 Torbjørn Skramstad Faglærer Abstract Steganography is about information hiding; to communicate securely or conceal the existence of certain data. The possibilities provided by steganography are appealing to criminals and law enforcement need to be up-to-date. This master thesis provides investigators with insight into methods and tools for steganog- raphy. Steganalysis is the process of detecting messages hidden using steganography and is examined together with methods to detect steganography usage. This report proposes digital forensic methods for retrieval and analysis of steganog- raphy during a digital investigation. -

Dorf Pankow Prenzlauer Berg Marzahn

Berlin Legende Information S- und U-Bahn-Linie Verkehrsverbund Schnellbahn Liniennetz Tarifbereich Berlin tariff area of Berlin mit Umsteigemöglichkeit Berlin-Brandenburg GmbH Rapid transit route map Suburban train and underground Infocenter line, changing trains optional Hardenbergplatz 2, 10623 Berlin O (030) 25 41 41 41 Linie des Regionalverkehrs Wittenberge Stralsund/Rostock Eberswalde/Frankfurt (Oder) OE60 Line of regional train Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) Kremmen Templin Stadt Groß Schönebeck NE27 10773 Berlin Schwedt/Stralsund Linie bzw. Bahnhof wird nicht regelmäßig bedient O (030) 19 44 9 Vehlefanz C Sachsenhausen C C Schmachtenhagen NE27 Wandlitzsee C Line/Station served seasonal or at weekends only S-Bahn Berlin GmbH Oranienburg 4A Kundenbüro C Wensickendorf NE27 Wandlitz C d Bärenklau C C C Strecke in Bau Invalidenstr. 19, 10115 Berlin Lehnitz d C d Zühlsdorf Rüdnitz d OHV d 4 A Bernau Transportation lines under O (030) 2974 33 33 Velten Borgsdorf C d d C Basdorf construction Hohen d 4A Bernau-Friedenstal Neuendorf West C Birkenwerder 4A d Fernbahnhof DB Regio AG Region Nordost d C RE6 RB20 RB20 RE5 RB12 Schönwalde Long-distance railway station O (0331) 235 68-81, 82 Hohen d Zepernick BAR 4A Schöner- Barrierefreier Zugang NEB Betriebsgesellschaft mbH d 4A Neuendorf Bergfelde Schönfließ Mühlenbeck- d 4A Hennigsdorf d 4A Mönchmühle C d d C linde Röntgental Good wheelchair access O (030) 39 60 11 31 4A Frohnau 4A d C Barrierefreier Zugang nur zu den Buch angegebenen Verkehrsmitteln Ostdeutsche Eisenbahn GmbH 4A Heiligensee -

Die Berliner Bezirke, Altbezirke Und Ortsteile

Geschäftsstelle des Gutachterausschusses für Grundstückswerte in Berlin Die Berliner Bezirke, Altbezirke und Ortsteile Aktuelle Bezirke Altbezirke Aktuelle Ortsteile Gebiets- Stadt- gruppe lage Nr. Name Name Name Name 01 Mitte Mitte Mitte City Ost Tiergarten Moabit City West Hansaviertel City West Tiergarten City West Wedding Wedding Nord West Gesundbrunnen Nord West 02 Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Friedrichshain Friedrichshain City Ost Kreuzberg Kreuzberg City West 03 Pankow Prenzlauer Berg Prenzlauer Berg City Ost Weißensee Weißensee Nord Ost Blankenburg Nord Ost Heinersdorf Nord Ost Karow Nord Ost Malchow Nord Ost Pankow Pankow Nord Ost Blankenfelde Nord Ost Buch Nord Ost Französisch Buchholz Nord Ost Niederschönhausen Nord Ost Rosenthal Nord Ost Wilhelmsruh Nord Ost 04 Charlottenburg-Wilmers- Charlottenburg Charlottenburg City West dorf Westend Südwest West Charlottenburg-Nord Nord West Wilmersdorf Wilmersdorf City West Schmargendorf Südwest West Grunewald Südwest West Halensee City West Stand:05.03.2020 Seite 1 / 3 Geschäftsstelle des Gutachterausschusses für Grundstückswerte in Berlin 05 Spandau Spandau Spandau West West Haselhorst West West Siemensstadt West West Staaken West West Gatow West West Kladow West West Hakenfelde West West Falkenhagener Feld West West Wilhelmstadt West West (West-Staaken)* West Ost 06 Steglitz-Zehlendorf Steglitz Steglitz Südwest West Lichterfelde Südwest West Lankwitz Südwest West Zehlendorf Zehlendorf Südwest West Dahlem Südwest West Nikolassee Südwest West Wannsee Südwest West 07 Tempelhof-Schöneberg Schöneberg -

Berlin District Centres of Adult Education

Urban Sustainability, Orientation Theory and Adult Education Infrastructure in the District – A Common Approach in the Case of the Berlin District Centres of Adult Education vorgelegt von Frau Dipl.-Ing. Anastasia Zefkili von der Fakultät VI Planen Bauen Umwelt der Technischen Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaft -Dr.-Ing. – genehmigte Dissertation Promotionsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Henckel Berichter: Prof. Pahl-Weber Berichter: Dr. Dienel Tag der wissenschaftlichen Aussprache: 10.09.2010 Berlin 2011 D 83 Acknowledgements The present work would not be possible without the support of a number of people with whom I had the pleasure to cooperate. I would like to express my gratitude to the experts and to the employees of the Berlin Volkshochschule, who dedicated their time and shared their knowledge and experience for the purpose of the current research. I would also like to thank my supervisors, Prof. Elke Pahl-Weber and Dr. Hans- Liudger Dienel, for their support, as well as Prof. Hartmut Bossel for his comments on my work. Furthermore, I am grateful to the Bakala Foundation for the financing of my studies and to the Women's Affairs Office for the Central University Administration for their support towards the conclusion of my thesis. In particular, I would like to thank Dr. Marcello Barisonzi, who supported me with technical advice and read my thesis. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Adult Education in Sustainable District Development . 1 1.2 Urban Issues at the District Level . 4 1.3 Trends in Adult Education . 10 1.3.1 Educational Infrastructure in the District . -

The Cold War

Konrad H. Jarausch, Christian F. Ostermann, Andreas Etges (Eds.) The Cold War The Cold War Historiography, Memory, Representation Edited by Konrad H. Jarausch, Christian F. Ostermann, and Andreas Etges An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-049522-5 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049617-8 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049267-5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover Image: BlackBox Cold War – Exhibition at Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin. Typesetting: Dr. Rainer Ostermann, München Printing: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Acknowledgements This volume grew out of an international conference on the history, memory and representation of the Cold War in Berlin. The editors would like to thank the following co-sponsors: the Berlin city government, the European Academy Berlin, the German Historical Institutes in Moscow, London, and Washington, the Centre for Contemporary History in Potsdam, the Military History Research Institute in Potsdam, the Allied Museum in Berlin, the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst, the Berlin Wall Foundation, the Airlift Gratitude Foundation (Stiftung Luftbrückendank) in Berlin, and the John F.