Magic Weapons and Armour in the Middle Ages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magic Wand Represents the Wandabsolute Will of the Magician

The Magic Wand represents the Wandabsolute will of the magician. This potent magical agic tool can be used for almost any energy-directing purpose, The M tinos which includes healing, the charging of other magical implements, and y Konstan the evocation of benevolent spirits (malevolent entities should be called with B the magic sword, which is explained below). Over the years, several occult orders and magical traditions have each developed specific magic wands for use in their rituals. The Golden Dawn, for example, had a different wand for every officer of the temple (Chief Adept's Wand, Praemonstrator's Wand, etc.), a wand for invoking the element of Fire (described above), and a Lotus Wand that was useful for many types of rituals. As a solitary ceremonial magician, however, you only need to concern yourself with the already explained Fire weapon and one other type of wand, the Magic Wand, which is used for directing energy and willpower. This Magic Wand does not have any particular elemental or astrological correspondences associated with it, therefore it is free of markings, unlike the Golden Dawn Elemental Weapons. The Magic Wand is a universal instrument, and can be used within the context of any magical current or tradition. When charging and consecrating your other magical weapons, this is the instrument you will use to help you direct energy and Divine Light into them. The type of material selected for a Magic Wand's construction is very important. Over the centuries, several different woods have been used and the ones recommended here are used almost universally. -

Author Book(S) Own Read Anderson, Poul the Broken Sword (1954)

Author Book(s) Own Read Anderson, Poul The Broken Sword (1954) The High Crusade (1960) Three Hearts and Three Lions (1953) Bellairs, John The Face in the Frost (1969) Brackett, Leigh * Sea-Kings of Mars and Otherworldly Stories Brown, Fredric * From these Ashes: The Complete Short SF of Fredric Brown Burroughs, Edgar Rice Mars series: A Princess of Mars (1912) The Gods of Mars (1914) The Warlord of Mars (1918) Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1920) The Chessmen of Mars (1922) The Master Mind of Mars (1928) A Fighting Man of Mars (1931) Swords of Mars (1936) Synthetic Men of Mars (1940) Llana of Gathol (1948) John Carter of Mars (1964) Pellucidar series: At the Earth’s Core (1914) Pellucidar (1923) Tanar of Pellucidar (1928) Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929) Back to the Stone Age (1937) Land of Terror (1944) Savage Pellucidar (1963) Venus series: Pirates of Venus (1934) Lost on Venus (1935) Carson of Venus (1939) Escape on Venus (1946) The Wizard of Venus (1970) Carter, Lin World’s End series: The Warrior of World’s End (1974) The Enchantress of World’s End (1975) The Immortal of World’s End (1976) The Barbarian of World’s End (1977) The Pirate of World’s End (1978) Giant of World’s End (1969) de Camp, L. Sprague Fallible Fiend (1973) Lest Darkness Fall (1939) de Camp, L. Sprague & Pratt, Fletcher Carnelian Cube (1948) Harold Shea series: The Roaring Trumpet (1940) The Mathematics of Magic (1940) The Castle of Iron (1941) The Wall of Serpents (1953) The Green Magician (1954) Derleth, August * The Trail of Cthulhu (1962) Dunsany, Lord * The King of -

Skaði Njörður Baldur + Ævintýrin

Grímnismál Einars Pálssonar. Þrymheimur Skaði, Breiðablik Baldur Skaði, skýr brúður goða (Baltasar) Sumar konur eru ráðríkar. Skaði er tákn um mikinn framkvæmdavilja, dugnað og drifkraft. -Það þýðir ekki að standa hér einsog hengilmæna. Farðu út og gerðu eitthvað í málinu. Goþrún dimmblá skráir mál litlu kjaftforu völvu Óðsmál in fornu ISBN 978-9935-409-40-9 1 21. ISBN 978-9935-409-20-1 Skaði Njörður Baldur og ævintýrin Göia goði, Óðsmál, http://www.mmedia.is/odsmal [email protected]; [email protected] Norræn menning ***************************************** +354 694 1264; +354 552 8080 Goþrún Dimmblá setur hér spássíukrot: Í Reykajvík var mikið af baldursbrá í gamla daga. Notuð var hún sem spájurt, sagði amma mín, þannig, að gott væri síldarár, mikil síldveiði, það árið sem mikið væri um baldursbrá. Baldursbráin heitir á ensku day’s eye, dags auga, sem úr verður daisy. Hún vex í sendnum og malarbornum jarðvegi við sjóinn. Ég sá erlenda ferðamenn taka nærmyndir af villtum blómum á Sæbrautinni. Smá og harðger fjörublóm voru þar í þúsundatali. Lág og jarðlæg, með fögur lítil blóm, sem sáust vart nema maður krypi á kné. 2 Þau nota oft litla steina sér til skjóls, en teygja smáar krónur sínar til birtunnar. Tigulegur njólinn, harðger og seigur, sást vel. Baldursbráin teygði sig upp í sólina. Heilu breiðurnar opnuðu krónur í átt til sólar, í austur að morgni, í suður yfir daginn, í vestur þegar degi tók að halla. Þessar jurtir eru einsog Íslendingar: beina augum til sólar, og láta salt særok ekki hafa áhrif á sig. Margar fjörujurtir, auk þangs og þara, voru manneldi gott í gegnum aldirnar. -

Song of El Cid

Eleventh Century Spain was fragmented into kingdoms and other domains on both the Christian and Muslim sides. These realms were continually at war among themselves. El Cid was a soldier- adventurer of this time whose legend endured through the centuries and became a symbol of the Christian Reconquest. This is his story as told by himself in the guise of a medieval troubadour – but with some present-day anachronisms creeping in. Song of El Cid I’m Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar; Prince Sancho was the one I served, my fame has spread to lands afar. my qualities were well observed, that’s why you’re sitting here with me so when he became the king in turn to listen to my soliloquy. I had but little left to learn about the matters of warfare, To Moors I’m known as El Sayyid and to him allegiance I did swear. (though I am no Almorávide). El Cid, the lord or leader who As his royal standard bearer, I is invincible in warfare too. was one on whom he could rely to wage the battles against his kin, To Christians I’m El Campeador, which it was paramount to win. now what that means you can be sure. I’m champion of the field of battle, For in the will of Ferdinand, reducing all my foes to chattel! he had divided all his land; to García - Galicia, to Elvira – Toro, Confuse me not with Charlton Heston, to Alfonso - León, to Urraca - Zamora. my story’s not just any Western. His culture centers round the gun, So Sancho was left with Castile alone but I have owned not even one. -

The Prose Edda

THE PROSE EDDA SNORRI STURLUSON (1179–1241) was born in western Iceland, the son of an upstart Icelandic chieftain. In the early thirteenth century, Snorri rose to become Iceland’s richest and, for a time, its most powerful leader. Twice he was elected law-speaker at the Althing, Iceland’s national assembly, and twice he went abroad to visit Norwegian royalty. An ambitious and sometimes ruthless leader, Snorri was also a man of learning, with deep interests in the myth, poetry and history of the Viking Age. He has long been assumed to be the author of some of medieval Iceland’s greatest works, including the Prose Edda and Heimskringla, the latter a saga history of the kings of Norway. JESSE BYOCK is Professor of Old Norse and Medieval Scandinavian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Professor at UCLA’s Cotsen Institute of Archaeology. A specialist in North Atlantic and Viking Studies, he directs the Mosfell Archaeological Project in Iceland. Prof. Byock received his Ph.D. from Harvard University after studying in Iceland, Sweden and France. His books and translations include Viking Age Iceland, Medieval Iceland: Society, Sagas, and Power, Feud in the Icelandic Saga, The Saga of King Hrolf Kraki and The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. SNORRI STURLUSON The Prose Edda Norse Mythology Translated with an Introduction and Notes by JESSE L. BYOCK PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN CLASSICS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., -

La Tizona En Palacio

MILIIARIA, Revista de Cultura Militar ISSN: 0214-5765 2000. 14.157-167 La Tizona en Palacio Juan Antonio MARRERO CABRERA «Larga, pesada y fatal», casi como esta manía de los sucesivos gobiernos de llevarse de Madrid el Museo del Ejército, era la espada del gran emperador Carlomagno. La célebre Joyosa que con tanta belleza describe la primera can- ción de gesta francesa, El Cantar de Roldón: «Esta espada muda de reflejos treinta veces al día. Mucho podríamos hablar de la lanza con la que Nuestro Señor fue herido en la cruz. Carlos, por la gracia de Dios, posee su punta y la hizo engastar en la dorada empuñadura; y por este honor y por esta bondad la espada recibió el nombre de Joyosa. Los barones franceses no lo deben olvidar; por ella tienen el grito de guerra «Monjoya», y por ello ninguna gente puedeoponérsele»’. Dura, implacable, imposible de quebrantar como la voluntad oficial de qui- tarle a los madrileños uno de sus más importantes y venerados depósitos históri- cos, despojándoles de su Museo del Ejército, era la espada de Roldán. La famo- sa Durandarte que en vano trató de destruir el orgullo de la caballería andante, cuando se vio morir junto a los Doce Pares de Francia a manos de los españoles en la derrota de Roncesvalles, que tan sentidamente narra el cantar de gesta: «Roldán golpeó en una grisácea piedra y la hinde más de lo que se deciros. Cruje la espada, pero no se quiebra ni se rompe, sino que rebota hacia el cielo. Cuando el conde ve que no podrá romperla, muy dulcemente se lamenta...» «¡Ah, buena Durandarte malograda fuiste!.. -

A Welsh Classical Dictionary

A WELSH CLASSICAL DICTIONARY DACHUN, saint of Bodmin. See s.n. Credan. He has been wrongly identified with an Irish saint Dagan in LBS II.281, 285. G.H.Doble seems to have been misled in the same way (The Saints of Cornwall, IV. 156). DAGAN or DANOG, abbot of Llancarfan. He appears as Danoc in one of the ‘Llancarfan Charters’ appended to the Life of St.Cadog (§62 in VSB p.130). Here he is a clerical witness with Sulien (presumably abbot) and king Morgan [ab Athrwys]. He appears as abbot of Llancarfan in five charters in the Book of Llandaf, where he is called Danoc abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 179c), and Dagan(us) abbas Carbani Uallis (BLD 158, 175, 186b, 195). In these five charters he is contemporary with bishop Berthwyn and Ithel ap Morgan, king of Glywysing. He succeeded Sulien as abbot and was succeeded by Paul. See Trans.Cym., 1948 pp.291-2, (but ignore the dates), and compare Wendy Davies, LlCh p.55 where Danog and Dagan are distinguished. Wendy Davies dates the BLD charters c.A.D.722 to 740 (ibid., pp.102 - 114). DALLDAF ail CUNIN COF. (Legendary). He is included in the tale of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ as one of the warriors of Arthur's Court: Dalldaf eil Kimin Cof (WM 460, RM 106). In a triad (TYP no.73) he is called Dalldaf eil Cunyn Cof, one of the ‘Three Peers’ of Arthur's Court. In another triad (TYP no.41) we are told that Fferlas (Grey Fetlock), the horse of Dalldaf eil Cunin Cof, was one of the ‘Three Lovers' Horses’ (or perhaps ‘Beloved Horses’). -

Gylfaginning Codex Regius, F

Snorri Sturluson Edda Prologue and Gylfaginning Codex Regius, f. 7v (reduced) (see pp. 26/34–28/1) Snorri Sturluson Edda Prologue and Gylfaginning Edited by ANTHONY FAULKES SECOND EDITION VIKING SOCIETY FOR NORTHERN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON 2005 © Anthony Faulkes 1982/2005 Second Edition 2005 First published by Oxford University Press in 1982 Reissued by Viking Society for Northern Research 1988, 2000 Reprinted 2011 ISBN 978 0 903521 64 2 Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter Contents Codex Regius, fol. 7v ..........................................................Frontispiece Abbreviated references ....................................................................... vii Introduction ..........................................................................................xi Synopsis ..........................................................................................xi The author ..................................................................................... xii The title ....................................................................................... xvii The contents of Snorri’s Edda ................................................... xviii Models and sources ........................................................................ xx Manuscripts .............................................................................. xxviii Bibliography ...............................................................................xxxi Text ....................................................................................................... -

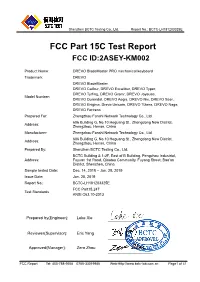

FCC Part 15C Test Report

Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E FCC Part 15C Test Report FCC ID:2ASEY-KM002 Product Name: DREVO BladeMaster PRO mechanical keyboard Trademark: DREVO DREVO BladeMaster DREVO Calibur, DREVO Excalibur, DREVO Typer, DREVO Tyrfing, DREVO Gramr, DREVO Joyeuse, Model Number: DREVO Durendal, DREVO Aegis, DREVO Nix, DREVO Seer, DREVO Enigma, Drevo Unicorn, DREVO Tizona, DREVO Naga, DREVO Fortress Prepared For: Zhengzhou Fanshi Network Technology Co., Ltd. 606 Building G, No.10 Heguang St., Zhengdong New District, Address: Zhengzhou, Henan, China Manufacturer: Zhengzhou Fanshi Network Technology Co., Ltd. 606 Building G, No.10 Heguang St., Zhengdong New District, Address: Zhengzhou, Henan, China Prepared By: Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. BCTC Building & 1-2F, East of B Building, Pengzhou Industrial, Address: Fuyuan 1st Road, Qiaotou Community, Fuyong Street, Bao’an District, Shenzhen, China Sample tested Date: Dec. 14, 2018 – Jan. 28, 2019 Issue Date: Jan. 28, 2019 Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E FCC Part15.247 Test Standards ANSI C63.10-2013 Prepared by(Engineer): Leke Xie Reviewer(Supervisor): Eric Yang Approved(Manager): Zero Zhou FCC Report Tel: 400-788-9558 0755-33019988 Web:Http://www.bctc-lab.com.cn Page1 of 41 Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E This device described above has been tested by BCTC, and the test results show that the equipment under test (EUT) is in compliance with the FCC requirements. The test report is effective only with both signature and specialized stamp.This result(s) shown in this report refer only to the sample(s) tested. Without written approval of Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd, this report can’t be reproduced except in full.The tested sample(s) and the sample information are provided by the client. -

Journey Planet 57—January 2021 ~Table of Contents~ 2

Arthur, King of the Britons Editors Chris Garcia, Chuck Serface, James Bacon Journey Planet 57—January 2021 ~Table of Contents~ 2 Page 5 King Arthur Plays Vegas: The Excalibur Editorial by Christopher J. Garcia by Christopher J. Garcia Page 38 Page 7 In Time of Despair and Great Darkness Letters of Comment by Ken Scholes by Lloyd Penney Page 49 Page 12 Camelot Instant Fanzine Article: Arthur and Merlin by Laura Frankos by Christopher J. Garcia and Chuck Serface Page 55 Page 16 A Retro-Review: Monty Python’s Spamalot The Story of Arthur by Steven H Silver Retold by Bob Hole Page 58 Page 19 Arthurs for Our Time: Recent Interpretations Arthur, Alfred, and the Myth of England of the Legend by Julian West by Chuck Serface Page 62 Page 23 Lady Charlotte and King Arthur Two Cups of Blood: Dracula vs. King Arthur by Cardinal Cox by Derek McCaw Page 64 Page 29 From a Certain Point of View: Merlin & Nimue Knights of Pendragon: The Other Arthurian Comic by Steven H Silver by Helena Nash Page 31 Page 75 Interview with Dorsey Armstrong Tristan, Isolde, and Camelot 3000 by Christopher J. Garcia by Christopher J. Garcia Page 35 King Arthur in Fifteen Stamps Page 77 by Bob Hole “It’s Only a CGI Model”: Arthurian Movies of the Twenty-First Century Page 36 by Tony Keen Arthur, King of the Britons 3 ~Table of Contents~ Page 81 Cover by Vanessa Applegate Terry Gilliam's The Fisher King by Neil Rest Page 1—DeepDreamGenerator Combination of Page 84 King Arthur Tapestry of the Nine Worthies and My Barbarian’s “Morgan Le Fey” . -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Image and Reality In

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Image and Reality in Medieval Weaponry and Warfare: Wales c.1100 – c.1450 Colcough, Samantha Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 BANGOR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HISTORY, WELSH HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY Note: Some of the images in this digital version of the thesis have been removed due to Copyright restrictions Image and Reality in Medieval Weaponry and Warfare: Wales c.1100 – c.1450 Samantha Jane Colclough Note: Some of the images in this digital version of the thesis have been removed due to Copyright restrictions [i] Summary The established image of the art of war in medieval Wales is based on the analysis of historical documents, the majority of which have been written by foreign hands, most notably those associated with the English court. -

The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Christopher R

Gettysburg College Faculty Books 2-2016 The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Christopher R. Fee Gettysburg College David Leeming University of Connecticut Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, and the Religion Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Fee, Christopher R., and David Leeming. The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother. London, England: Reaktion Press, 2016. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/books/95 This open access book is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Goddess: Myths of the Great Mother Description The Goddess is all around us: Her face is reflected in the burgeoning new growth of every ensuing spring; her power is evident in the miracle of conception and childbirth and in the newborn’s cry as it searches for the nurturing breast; we glimpse her in the alluring beauty of youth, in the incredible power of sexual attraction, in the affection of family gatherings, and in the gentle caring of loved ones as they leave the mortal world. The Goddess is with us in the everyday miracles of life, growth, and death which always have surrounded us and always will, and this ubiquity speaks to the enduring presence and changing masks of the universal power people have always recognized in their lives.