GLADIUS (CUBIERTA).Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song of El Cid

Eleventh Century Spain was fragmented into kingdoms and other domains on both the Christian and Muslim sides. These realms were continually at war among themselves. El Cid was a soldier- adventurer of this time whose legend endured through the centuries and became a symbol of the Christian Reconquest. This is his story as told by himself in the guise of a medieval troubadour – but with some present-day anachronisms creeping in. Song of El Cid I’m Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar; Prince Sancho was the one I served, my fame has spread to lands afar. my qualities were well observed, that’s why you’re sitting here with me so when he became the king in turn to listen to my soliloquy. I had but little left to learn about the matters of warfare, To Moors I’m known as El Sayyid and to him allegiance I did swear. (though I am no Almorávide). El Cid, the lord or leader who As his royal standard bearer, I is invincible in warfare too. was one on whom he could rely to wage the battles against his kin, To Christians I’m El Campeador, which it was paramount to win. now what that means you can be sure. I’m champion of the field of battle, For in the will of Ferdinand, reducing all my foes to chattel! he had divided all his land; to García - Galicia, to Elvira – Toro, Confuse me not with Charlton Heston, to Alfonso - León, to Urraca - Zamora. my story’s not just any Western. His culture centers round the gun, So Sancho was left with Castile alone but I have owned not even one. -

La Tizona En Palacio

MILIIARIA, Revista de Cultura Militar ISSN: 0214-5765 2000. 14.157-167 La Tizona en Palacio Juan Antonio MARRERO CABRERA «Larga, pesada y fatal», casi como esta manía de los sucesivos gobiernos de llevarse de Madrid el Museo del Ejército, era la espada del gran emperador Carlomagno. La célebre Joyosa que con tanta belleza describe la primera can- ción de gesta francesa, El Cantar de Roldón: «Esta espada muda de reflejos treinta veces al día. Mucho podríamos hablar de la lanza con la que Nuestro Señor fue herido en la cruz. Carlos, por la gracia de Dios, posee su punta y la hizo engastar en la dorada empuñadura; y por este honor y por esta bondad la espada recibió el nombre de Joyosa. Los barones franceses no lo deben olvidar; por ella tienen el grito de guerra «Monjoya», y por ello ninguna gente puedeoponérsele»’. Dura, implacable, imposible de quebrantar como la voluntad oficial de qui- tarle a los madrileños uno de sus más importantes y venerados depósitos históri- cos, despojándoles de su Museo del Ejército, era la espada de Roldán. La famo- sa Durandarte que en vano trató de destruir el orgullo de la caballería andante, cuando se vio morir junto a los Doce Pares de Francia a manos de los españoles en la derrota de Roncesvalles, que tan sentidamente narra el cantar de gesta: «Roldán golpeó en una grisácea piedra y la hinde más de lo que se deciros. Cruje la espada, pero no se quiebra ni se rompe, sino que rebota hacia el cielo. Cuando el conde ve que no podrá romperla, muy dulcemente se lamenta...» «¡Ah, buena Durandarte malograda fuiste!.. -

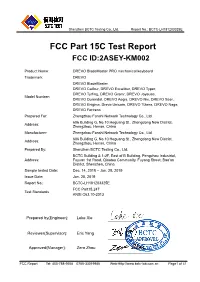

FCC Part 15C Test Report

Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E FCC Part 15C Test Report FCC ID:2ASEY-KM002 Product Name: DREVO BladeMaster PRO mechanical keyboard Trademark: DREVO DREVO BladeMaster DREVO Calibur, DREVO Excalibur, DREVO Typer, DREVO Tyrfing, DREVO Gramr, DREVO Joyeuse, Model Number: DREVO Durendal, DREVO Aegis, DREVO Nix, DREVO Seer, DREVO Enigma, Drevo Unicorn, DREVO Tizona, DREVO Naga, DREVO Fortress Prepared For: Zhengzhou Fanshi Network Technology Co., Ltd. 606 Building G, No.10 Heguang St., Zhengdong New District, Address: Zhengzhou, Henan, China Manufacturer: Zhengzhou Fanshi Network Technology Co., Ltd. 606 Building G, No.10 Heguang St., Zhengdong New District, Address: Zhengzhou, Henan, China Prepared By: Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. BCTC Building & 1-2F, East of B Building, Pengzhou Industrial, Address: Fuyuan 1st Road, Qiaotou Community, Fuyong Street, Bao’an District, Shenzhen, China Sample tested Date: Dec. 14, 2018 – Jan. 28, 2019 Issue Date: Jan. 28, 2019 Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E FCC Part15.247 Test Standards ANSI C63.10-2013 Prepared by(Engineer): Leke Xie Reviewer(Supervisor): Eric Yang Approved(Manager): Zero Zhou FCC Report Tel: 400-788-9558 0755-33019988 Web:Http://www.bctc-lab.com.cn Page1 of 41 Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd. Report No.: BCTC-LH181203325E This device described above has been tested by BCTC, and the test results show that the equipment under test (EUT) is in compliance with the FCC requirements. The test report is effective only with both signature and specialized stamp.This result(s) shown in this report refer only to the sample(s) tested. Without written approval of Shenzhen BCTC Testing Co., Ltd, this report can’t be reproduced except in full.The tested sample(s) and the sample information are provided by the client. -

El Cid Recupera Su Espada, La Tizona 20MINUTOS.ES / EFE

http://www.20minutos.es/noticia/238479/0/cid/espada/tizona/ El Cid recupera su espada, la Tizona 20MINUTOS.ES / EFE. 24.05.2007 - 08:17h La Tizona, espada del Cid, en el museo del Ejército (Juan Antonio Martínez / EFE). • La ha comprado la Junta de Castilla y León a su actual dueño, el marqués de Falces. • Su precio: 1,6 millones de euros. • Será depositada junto a los restos del Cid, en la catedral de Burgos. La Junta de Castilla y León ha adquirido por 1,6 millones de euros la Tizona , la espada del Cid Campeador (1043-1099), que de forma provisional ha sido depositada en el Museo de Burgos, aunque su destino final será previsiblemente la catedral de la ciudad, donde se encuentran los restos mortales del Campeador. La espada, hasta ahora propiedad de José Ramón Suárez de Otero, marqués de Falces, se encontraba en el Museo del Ejército de Madrid hasta su reciente cierre. Su dueño la ofreció primero al ministerio de Cultura, según explicó a Efe la consejera de Cultura y Turismo de Castilla y León, Silvia Clemente. Sin embargo, el ministerio la rechazó, por lo que el marqués de Falces comunicó a la Junta su intención de venderla. La Tizona será la pieza protagonista de la exposición que comenzará el próximo septiembre en la catedral de Burgos sobre Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, con motivo de la conmemoración del octavo centenario del Cantar de Mío Cid . Una de las dos espadas del Cid Según cuenta la leyenda, el Cid Campeador recibió la Tizona de manos de sus yernos, los infantes de Carrión, justo antes de que se desposaran con sus hijas, doña Elvira y doña Sol. -

Bugbear Distinct from Other Goblinoids, Bugbear Name Their Offspring After Any Number of Things

INTRODUCTION For some Dungeon Masters, one of the trickiest parts of running a campaign is coming up with consistent character names, especially on the fly. Every dungeon master has been in that situation at one point or another; the players have a longer conversation with Village Guard #3 than you anticipated, get invested in them, and want to know their name. This book takes that issue and extends it to some of the less common Dungeons and Dragons races which have been released through officially published material. Why Use This Book? Name generators found online are an invaluable tool for dungeon masters, but finding the right one can be very hit and miss. This book strives to have names which are consistently themed, flavorful, and able to be pronounced at a glance. Using This Book This book has two main table types to roll on: Percentile and Double-Sixty. Percentile tables contain 100 names all ready to go. Simply roll a percentile die or a pair of d10s and go to that point in the table to get your name. Double-Sixty tables have 120 entries divided into two 6x10 blocks. Each entry is one half of the name with the top block going first and the bottom block going second. Roll a d6 to determine the column and a d10 to find the row for the first half, then repeat for the second half. Finally, combine the two halves to get your name. Thank You! To everyone who bought this book, told their friends, or shared it with someone, your support is encouraging me to make bigger and better projects! Thank you! ~J.L. -

Magic Weapons and Armour in the Middle Ages

1 ‘No weapon could bite him’ – Magic weapons and armour in the middle ages Magic weapons and armour are things we usually associate with the realms of myth or fantasy rather than history. And yet, in semi-historical and even historical sources throughout the medieval period we find accounts of magic weapons which bring down foes or inspire comrades, or of shields and armour which protect the wearer no matter what they faced. What is more, it is clear that there is a historical reality at play in such mythological accounts and we can see a clear development of how mundane equipment came to be considered magical. ‘I shall call thee …’ The tradition of named weapons The tradition of named weapons is well known – Siegfried’s sword Balmung (or Nothung), Thor’s hammer Mjölnir, Arthur’s Excalibur, or Attila’s ‘Sword of Mars’ (Jordanes Getica 35) and many, many others. As can be seen in these examples we can easily transition from myth to semi- historical, and into historical characters, all of whom had named weapons. Indeed, the history of named weapons dates back to antiquity and there are literally hundreds of them across all cultures where swords, and any other weapon type you care to name, were used: Scandanavian, Near Eastern, Indian, South-East Asian, Greek and Roman, Germanic and Celtic. In a similar vein, the history of named ships is an old one and one which continues today. In the medieval period we have Arthur’s ship, with the same name as his shield, Prydwen (meaning ‘fair-face’), and the Norse god Baldur’s ship Hringhorni, the greatest of all ships, and others. -

Reinventing the Sword

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan Charles Edward Ethridge Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Ethridge, Charles Edward, "Reinventing the sword: a cultural comparison of the development of the sword in response to the advent of firearms in Spain and Japan" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 3729. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3729 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REINVENTING THE SWORD: A CULTURAL COMPARISON OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE SWORD IN RESPONSE TO THE ADVENT OF FIREARMS IN SPAIN AND JAPAN A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Charles E. Ethridge B.A., Louisiana State University, 1999 December 2007 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Fredrikke Scollard, whose expertise, understanding, and patience added considerably to my graduate experience. I appreciate her knowledge of Eastern cultures and her drive to promote true ‘cross-cultural’ research. -

The Sword of the Spirit, the Word of God

The Sword of the Spirit, the Word of God The sixth piece of armor Paul mentions in Ephesians 6 is "the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God." How does a Roman soldier's sword help us understand how to use the Bible to win our spiritual battles? The Bible, in Judges 7, records the story of Gideon and his 300 men: Gideon and 32,000 Israelite troops gathered near the Midianite camp, but they were severely outnumbered by their 135,000 oppressors. Gideon was ready to do battle, but God had other plans. He was about to show His people just how powerful a God He was. God told Gideon to let anyone who was afraid of the upcoming battle return home. Twenty-two thousand men took the opportunity to leave their ranks, leaving only 10,000 remaining. But God was looking for a smaller group still. God then told Gideon to have the remainder drink from the spring, and all those who lapped the water like a dog would remain, while the rest were sent home. Finally, with only 300 men, Gideon and his little army surrounded the Midianites. On signal they blew trumpets, broke the pitchers covering their torches and shouted, "The sword of the Lord and of Gideon!" (Judges 7:20). Then the unthinkable happened. These 300 men—holding not swords, but torches and trumpets—routed the entire Midianite camp. Scripture records that God "set every man's sword against his companion throughout the whole camp" (Judges 7:22). So before the Israelites even had a chance to reach for swords, God plunged the enemy camp into chaos and wild defeat. -

De La Edad De Los Imperios a La Guerra Total: Medievo Y Videojuegos

ISBN 978-84-944757-9-5 ISBN 978-84-944757-9-5 Colección Historia y Videojuegos 9788494 475795 9788494 475795 3 DE LA EDAD DE LOS IMPERIOS A LA GUERRA TOTAL: MEDIEVO Y VIDEOJUEGOS Juan Francisco Jiménez Alcázar DE LA EDAD LOS IMPERIOS A GUERRA TOTAL: MEDIEVO Y VIDEOJUEGOS Proyecto de investigación I+D+I: Proyecto de investigación I+D+I: Historia y videojuegos: el impacto Historia y videojuegos: el impacto de los nuevos medios de ocio de los nuevos medios de ocio sobre el conocimiento del pasado sobre el conocimiento del pasado medieval (HAR2011-25548) medieval (HAR2011-25548) 3 Juan Francisco Jiménez Alcázar De la Edad de los Imperios a la Guerra Total: Medievo y videojuegos Colección Historia y Videojuegos nº 3 Primera edición, 2016 Reservados todos los derechos. El contenido de esta obra está protegido por la Ley, que establece penas de prisión y/o multa, además de las correspondientes indemnizaciones por daños y perjuicios, para quienes reprodujesen, plagien, distribuyan o comuniquen públicamente, en todo o en parte, una obra literaria, artística o científica, o su transformación, interpretación o ejecución artística fijada en cualquier tipo de soporte o comunicada a través de cualquier medio, sin la preceptiva autorización. Proyecto de investigación I+D+I: Historia y videojuegos: el impacto de los nuevos medios de ocio sobre el conocimiento del pasado medieval (HAR2011-25548). Financiado por el Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad del Gobierno de España. Colección Historia y Videojuegos, 3 Edición a cargo de Compobell, S.L. © Juan Francisco Jiménez Alcázar I.S.B.N.: 978-84-944757-9-5 Depósito Legal: MU 392-2016 Diseño e impresión: Compobell, S.L. -

The Armour of God the Sword of the Spirit, the Word Of

The Great Teachings of the Bible and What They Mean for You: The Armour of God The apostle Paul listed many defensive pieces of the armour of God, but only one was an offensive weapon. What does God want us to learn from the sword of the Spirit? In this lesson, let's explore what the Bible says about the sword of the Spirit, the Word of God. The Sword of the Spirit, the Word of God The sixth piece of armour Paul mentions in Ephesians 6 is "the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God." How does a Roman soldier's sword help us understand how to use the Bible to win our spiritual battles? The Bible, in Judges 7, records the story of Gideon and his 300 men: Gideon and 32,000 Israelite troops gathered near the Midianite camp, but they were severely outnumbered by their 135,000 oppressors. Gideon was ready to do battle, but God had other plans. He was about to show His people just how powerful a God He was. God told Gideon to let anyone who was afraid of the upcoming battle return home. Twenty-two thousand men took the opportunity to leave their ranks, leaving only 10,000 remaining. But God was looking for a smaller group still. God then told Gideon to have the remainder drink from the spring, and all those who lapped the water like a dog would remain, while the rest were sent home. Finally, with only 300 men, Gideon and his little army surrounded the Midianites. -

Famed Magical Swords of the Isle of Delrith

FAMED MAGICAL SWORDS OF THE ISLE OF DELRITH [Player’s note: These swords range significantly in power. The first are the most famous swords of the isle, the last are famous only in the south, some only in the west of Grozney.] LEGENDARY MAGICAL SWORDS LONGSWORDS Unless otherwise noted, all longswords are between 39 and 41 inches long and have a blade 33 to 35 inches long. Joyuese: The sword of king Delrith. A silver bladed longsword of fine quality, rumored to be a great bane to evil creatures and the goblin races. The sword has a diamond set in the hilt and a platinum falcon head on each quillón. Grus: An ancient sword belonging to the old high king of the isle before the coming of the Companions. A wide longsword with upturned quillóns, the pommel is a lion’s head, the hilt is made of bronze and the blade is black as death. Legend says the lion’s eyes are made of fire. This sword is often copied. Heaven’s Will: The sword used by the paladin Dunstan when he helped drive out the demon hordes of Demigorgon almost 600 years ago. The sword has a 7-sided pommel, and qullóns ending in a platinum dragon’s head, each eye deep set with an emerald. The blade shines as silver and places a silvery light throughout the surrounding area. Fragarach: Another famous sword of a former high king, this sword passes through armour and shields as if they were not there, allows the wielder to control the wind, and forces those to whom it is raised to speak the truth. -

Iron, Steel and Swords Script

2. Swords, Iron and Steel 2.1 Swords 2.1.1 What, Beyond the Obvious, are Swords? What, exactly, are swords? Stupid question - don't we all know? Well, we shall see about that. Just to give you a taste treat of what follows, I make this claim: Some swords are pieces of art and part of your cultural heritage. Read on if you do believe me, and in particular if you don't believe me. Some swords are pieces of art, not all. You will find examples of the former on display in major museums. While most of those museum pieces were also perfect weapons for combat, changes are that they have never been used for killing or wounding people. Be that as it may, it is also absolutely necessary to point out that most swords were not primarily pieces of art but just tools for killing or wounding "the enemy". Most of those "utility" swords have rusted away by now or get dusty in attics and minor museums (including army museums). If you think a bit about that you realize that killing or wounding people is pretty much the only direct use of a sword. You could kill or wound people with your knife too, not to mention your car. But in contrast to your knife, you can't use your sword to butter your bread, to cut your steak, to clean your fingernails or to cut a hiking staff from the next hazelnut bush. I want to be very clear about the following: Swords are evil objects if you consider only their intended or actual use as weapons.