Detailprogramm Der Tagung

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Gruntz Aus Der Rille

2 Aus der Rille George Gruntz Ein Beitrag von Thomas König Nomen est omen! Oder wenn Orden schmücken den Weg von war. Die Arbeiterfamilie Gruntz presste ein Pianist, Komponist, Band- George Gruntz in der zweiten Hälfte George in eine Maschinenzeichnerleh- leader, Leiter, Lehrer oder ein- des letzten Jahrhunderts, vom zweit- re, schliesslich sollte man einen anstän- fach Musikmacher und -orga- höchsten Orden der Bundesrepublik digen Beruf erlernen, war die einstim- nisator seit mehr als 50 Jahren Deutschland bis zum Kulturpreis seines mig familiäre Meinung. Die schloss er der ganzen Welt zeigt, dass Wohnkantons, dem Baselbiet, welchen 1951 auch mit besonderer Anerken- die Schweiz mehr zu bieten hat er 1994 erhielt. nung ab, aber eigentlich lebte er zu die- als Milch, Kühe, Schokolade, ser Zeit für das Klavier und dessen Un- Berge, Uhren und Banken… terricht, den er sich beim bekannten Leh- rer am Basler Konservatorium, Eduard Henneberger, leisten konnte. So wurde das «Wohltemperierte Klavier» zum Pflichtstudium des jungen George, der zu jener Zeit primär seinem Vorbild Bud Powell nachzueifern trachtete, aber mit klassischen Mitteln seine Technik ver- bessern wollte und konnte. Auch die Berufslehre machte ihm durchaus Spass, aber es waren vor al- lem auch Lebenserfahrungen, wie zum Beispiel Ausflüge nach Paris, welche den jungen Maschinenzeichner faszi- nierten und sowohl menschlich wie mu- sikalisch weiter brachten. Da konnte er MPS 21 22188-1 George Gruntz: Als weisser Neger geboren – Ein Leben für den Jazz sowohl bei einer Jamsession einsteigen ISBN 3-9522460-1-8 und mitmachen, wie auch im Pigalle Vieles tun und doch nur etwas die Bekanntschaft mit liebeserfahrenen wollen Wenn der Anfang nicht nur Damen machen… schwer ist, sondern zu einer Fast ein Vierteljahrhundert hat er die Frage der Existenz wird. -

Franco Ambrosetti Jazz-Trompeter Im Gespräch Mit Roland Spiegel

Sendung vom 7.3.2016, 20.15 Uhr Franco Ambrosetti Jazz-Trompeter im Gespräch mit Roland Spiegel Spiegel: Herzlich willkommen zum alpha-Forum. Ich freue mich heute auf einen Gast, der jahrzehntelang ein sehr, sehr spannendes Doppelleben geführt hat, nämlich eines als Industrieller und eines als weltberühmter Jazztrompeter. Herzlich willkommen, Franco Ambrosetti. Ambrosetti: Vielen Dank für die Einladung. Spiegel: Herr Ambrosetti, gleich am Anfang die Frage, wie es eigentlich möglich ist, zugleich ein Unternehmen zu führen und trotzdem auf dem Instrument so intensiv zu üben, dass man auf allerhöchstem Niveau mithalten kann über Jahrzehnte hinweg. Ambrosetti: Üben, das ist die erste Antwort. Aber ich muss auch sagen, dass ich als Student ziemlich lange studiert habe, sechs, sieben Jahre. Und in dieser Zeit habe ich hauptsächlich Trompete gespielt. Die Universität habe ich dabei fast nie von innen gesehen, bis mein Vater eines Tages gesagt hat: "So, jetzt ist es genug, jetzt musst du dich entscheiden. Entweder bist du Musiker oder du wirst Unternehmer." In diesen Jahren damals habe ich wirklich fünf bis sechs Stunden pro Tag geübt. Als ich dann nach dem Studienabschluss angefangen habe zu arbeiten als Unternehmer, habe ich eine Stunde pro Tag geübt, vielleicht auch mal Eineinviertel- oder Eineinhalbstunden oder halt weniger, wenn es nicht anders ging. Das Problem ist, dass man jeden Tag üben muss. Wenn man auf Geschäftsreise ist, dann ist es schon ein bisschen kompliziert, in den Hotels zu üben: Die Leute mögen das nicht so gerne. Ich habe dann aber herausgefunden, dass es ein System gibt, durch das ich das machen kann: Ich habe angefangen, in den Kleiderschrank zu spielen. -

The Band Directed by George Gruntz

The Band Live At The Schauspielhaus mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Live At The Schauspielhaus Country: Germany Released: 1976 Style: Big Band, Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1359 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1512 mb WMA version RAR size: 1946 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 573 Other Formats: MP1 MP4 DTS MPC MOD RA MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits Triple Hip Trip Composed By – Daniel HumairFeaturing, Bass Saxophone – Howard Johnson Featuring, A1 7:36 Synthesizer [Arp 2600] – George GruntzSoloist, Tenor Saxophone – Alan SkidmoreSoloist, Trumpet – Benny Bailey Epitaph For A Friend A2 Composed By, Soloist, Flugelhorn – Franco AmbrosettiFeaturing, Clarinet – Eddie 11:27 DanielsSoloist, Soprano Saxophone – Charlie MarianoSoloist, Trombone – Jimmy Knepper Nix Tango-Time A3 Composed By – The Band Soloist, Percussion – Dom Um RomaoSoloist, Tuba – Howard 3:15 Johnson Alpen Honky-Fonk B1 4:47 Composed By – Flavio AmbrosettiSoloist, Trumpet – Franco Ambrosetti El Commendador B2 Composed By, Soloist, Soprano Saxophone – Flavio AmbrosettiSoloist, Flugelhorn – Palle 10:37 MikkelborgSoloist, Flute – Eddie Daniels The Mazurka Composed By – George GruntzFeaturing, Drums – Daniel HumairFeaturing, Tuba – B3 6:48 Howard Johnson Soloist, Reeds [Nagaswaram] – Charlie MarianoSoloist, Trumpet – Jon Faddis Companies, etc. Recorded At – Schauspielhaus Zürich Recorded At – Tonstudio Bauer Credits Arranged By, Directed By, Leader [Co-leader], Electric Piano [Rhodes], Synthesizer – George Gruntz Bass – Niels H.Ø. Petersen* Design [Coverdesign] -

Jazzletter 27

swissjazzorama jazzletter Nr. 27, März 2013 EDITORIAL GEORGE GRUNTZ Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser Noch nie gab es einen Jazzletter, 24.6.1932 –10.1.2013 in dem wir über den Tod so vieler Schweizer Jazzgrössen zu berichten hatten. Gleich auf unserer Titelseite ehren wir George Gruntz, einen Musiker von herausragender Bedeutung. Die vielen Zeugnisse seines Schaffens sollen bei uns PIANIST sicher erhalten bleiben. BANDLEADER Kaum ein Freund von Jazz und ARRANGEUR Blues hat mit soviel Konsequenz all das gesammelt, was während Jahr- KOMPONIST zehnten in irgendeiner Weise den Jazz in der Schweiz dokumentiert DIRIGENT hat. Was Hans Philippi geleistet hat, auch er ein Basler wie George RADIOMODERATOR Gruntz, stellen wir Ihnen auf den FESTIVALLEITER Seiten 2 und 3 vor und berichten darüber, wie sich Mario Schnee- BERLINER JAZZTAGE berger bemüht hat, Philippis Rie- senmenge an Dokumenten in einen CONCERT JAZZ BAND geordneten Rahmen zu bringen. ZÜRCHER SCHAUSPIELHAUS Hier auf alles hinzuweisen, was es NEWPORT JAZZFESTIVAL in diesem Jazzletter zu lesen gibt, ginge zu weit. Sie werden bei der WORLD JAZZ OPERA Lektüre feststellen, dass wir auch dieses Mal in der Wahl unserer AUTOBIOGRAFIE: Beiträge die ganze Bandbreite von Jazz und Blues berücksichtigt ALS WEISSER NEGER GEBOREN haben. WA Herzlich Es wäre vermessen, hier ausführlich sehr nahe stand, war tatsächlich, beschreiben zu wollen, was der ein- wie Uli Bernays am 14. Januar zigartige George Gruntz in seinem in seiner Würdigung in der NZZ Antworten waren so bedeutungs- Leben als Musiker alles geschaffen geschrieben hat, der international voll, dass wir sie mindestens teil- hat. Am 10. Januar ist er nach langer erfolgreichste Jazzmusiker der weise in einer ausführlichen Würdi- Krankheit im Kreise seiner Familie Schweiz. -

George Gruntz.Pdf

Kultur «Wer nur von Jazz etwas versteht, der versteht nichts von Jazz» Interview mit mit George Gruntz von Niggi Freundlieb Mit einem Paukenschlag wird das diesjährige Jazzfestival Basel am 30. April eröffnet: George Gruntz tritt mit seiner Concert Jazz Band auf und unterstreicht damit die Bedeutung des Festivals als eines der mittlerweile wichtigsten Europas. Es ist aber auch ein Wiedersehen und -hören mit dem bedeutendsten Schweizer Musiker, Kom- ponisten, Arrangeur und Bandleader der Gegenwart, der in seiner langen Karriere als Mittler zwischen den musikalischen Welten als einer der Pioniere der Transformation des Jazz zur Weltmusik gilt. eorge Gruntz’ musikalische Ver- dienste aufzuzählen, hiesse, Trom- peten nach New Orleans zu tragen und würde den Rahmen des vorlie- gendenG Artikels sprengen. Einige Highlights des in Allschwil, ein paar Meter von der Kan- tonsgrenze zu Basel, lebenden 79-Jährigen, der zwar den Baselbieter Kulturpreis, aber noch nie dessen baselstädtisches Pendant er- halten hat (!) – er freut er sich jedoch ebenso über den Titel des «Ehrenspalenberglemers» oder viele andere Auszeichnungen, wie zum Beispiel das «Verdienstkreuz erster Klasse des Verdienstordens der Bundesrepublik Deutsch- land» – seien aber dennoch festgehalten: Geschäftsführer 01/2011 110113_rona_layout_auswahl_RZ.indd 1 1/14/2011 9:41:27 AM Kultur Man kann ihm nur zu «seinem» Festival gratulieren und sich dafür bedanken, was er für den Jazz tut. George Gruntz über Urs Blindebacher George Gruntz’ internationale Karriere star- Internationalen Musikfestwochen -

Final Programme ECTES 2012 13Th European Congress of Trauma & Emergency Surgery Many Ways – One Goal

Final_Programme_2012 24.04.12 15:29 Seite U1 Final Programme ECTES 2012 13th European Congress of Trauma & Emergency Surgery many ways – one goal May 12 – 15, 2012 Basel / Switzerland © Standortmarketing Basel Organised by European Society for Trauma & Emergency Surgery In cooperation with SGTV: Swiss Society of Traumatology and Insurance Medicine SGACT: Swiss Society for General Surgery and Traumatology SGACT SSCGT Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Allgemeinchirurgie und Traumatologie Société Suisse de Chirurgie Générale et de Traumatologie Società Svizzera di Chirurgia Generale e Traumatologia www.estesonline.org Final_Programme_2012 24.04.12 15:29 Seite U2 *smith&nephew TRIGEN™ SAFE Distal Locking without Fluoroscopy SURESHOT™ Distal Targeting System CONVENIENT Surgeon is in full control ACCURATE Enhanced Distal Screw Alignment Contact your local Smith & Nephew representative for more information Smith & Nephew Orthopaedics AG | Schachenalle 29 | 5001 Aarau | Switzerland | Phone +41 (0)62 832 06 06 | www.smith-nephew.com ™ Trademark of Smith & Nephew Final_Programme_2012 24.04.12 15:29 Seite 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome . 2 Important Addresses . 4 Organisation & Committees . 6 ESTES Board of Directors . 7 Acknowledgements of Guest Societies . 8 Sponsor Acknowledgements . 9 Exhibition . 10 Exhibition Floor Plan . 11 Registration Area . 12 Congress Information . 14 Congress Guidelines & Information . 16 Opening Hours Preview Centre . 16 If you are a Chairperson . 16 If you are a Speaker in a Session . 16 If you are presenting a Poster/in a Poster Session . 17 Official Social Programme . 18 Tours & Excursions . 21 General Information Basel . 22 ESTES Society . 25 Scientific Congress Programme at a Glance . 27 Scientific Congress Programme . 30 Sunday, May 13 . .30 Monday, May 14 . 56 Tuesday, May 15 . -

LS Break in Jazz.Indd

Milano Break in Jazz Piazza dei Mercanti Giovedì 06/13/20.IX.07 Tony Arco Time Percussion ore 13 Franco D’Andrea pianoforte Franco Cerri Guitar Ensemble Bruno De Filippi armonica a bocca Workshop Big Band dei Civici Corsi di jazz dell’Accademia Internazionale della Musica 5° Fabio Jegher direttore Franco Ambrosetti tromba Torino Milano Festival Internazionale della Musica 03_27.IX.07 Prima edizione SettembreMusica Break in Jazz Giovedì 06.IX ore 13 Tony Arco Time Percussion con gli studenti dei Civici Corsi di Jazz dell’Accademia Internazionale della Musica Con la partecipazione di Franco D’Andrea, pianoforte Giovedì 13.IX ore 13 Franco Cerri Guitar Ensemble con gli studenti dei Civici Corsi di Jazz dell’Accademia Internazionale della Musica Con la partecipazione di Bruno De Filippi, armonica a bocca Giovedì 20.IX ore 13 Workshop Big Band dei Civici Corsi di Jazz dell’Accademia Internazionale della Musica Fabio Jegher, direttore Con la partecipazione di Franco Ambrosetti, tromba In collaborazione con Fondazione Scuole Civiche di Milano Associazione Culturale Musica Oggi La Musica e l’Economia, percorso realizzato con Camera di Commercio di Milano, partner istituzionale di MITO SettembreMusica Break in Jazz Tony Arco Testo a cura di Maurizio Franco Percussioni Musica Oggi Break in Jazz è una manifestazione che da undici anni, da maggio a giugno, Nato a Milano nel 1965, Tony Arco inizia lo studio dello strumento all’età di propone nell’orario del “break” (dalle ore 13 alle ore 14) il complesso e tredici anni sotto la guida del Maestro Lucchini. A sedici anni incontra Tullio articolato lavoro didattico degli studenti dei Civici Corsi di Jazz di Milano. -

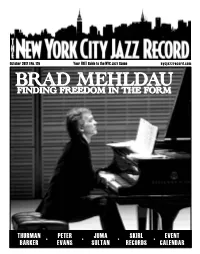

Finding Freedom in the Form Brad Mehldau

October 2012 | No. 126 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com FINDING FREEDOM IN THE FORM BRAD MEHLDAU THURMAN • PETER • JUMA • SKIRL • EVENT BARKER EVANS SULTAN RECORDS CALENDAR CHUSEOK JOHN SCOFIELD TRIO RAY GELATO GRP 30TH ANNIVERSARY GADI LEHAVI YOUNGJOO SONG & FT. STEVE SWALLOW & BILL STEWART 10/8 FT. DAVE GRUSIN, LEE RITENOUR & 10/15 SANGMIN LEE 10/2-7 DIANE SCHUUR 10/1 10/9-14 DIZZY GILLESPIETM IMANI UZURI BANN BUIKA ALUMNI ALL-STARS 10/22 JIMMY HEATH 86TH SEAMUS BLAKE, JAY ANDERSON, 10/30, 11/1 - 2 FT. PAQUITO D’RIVERA & BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION OZ NOY, ADAM NUSSBAUM CYRUS CHESTNUT 10/23-28 10/29 10/16-21 LATE NIGHT GROOVE SERIES: SUNDAY BRUNCH SERIES: BIG BROOKLYN RED 10/5 NYU JAZZ: COMBO NUVO 10/7 SPARKPLUG 10/6 ASSAF KEHATI TRIO 10/14 ANDY MILNE & DAPP THEORY 10/12 CECILE McLORIN SALVANT W/ AARON DIEHL TRIO 10/21 GORDON CHAMBERS 10/13 JUILLIARD JAZZ: TRIBUTE TO ART BLAKEY GABRIEL JOHNSON 10/19 AND THE JAZZ MESSENGERS 10/28 WYLLYS FEATURING PETER APFELBAUM 10/20 JEREMY MAGE 10/26 MELISSA NADEL 10/27 TELECHARGE.COM TERMS, CONDITIONS AND RESTRICTIONS APPLY One of the things that makes jazz so appealing is that, despite being a ‘genre’ unto itself, across its century-plus history, it has incorporated pretty much every other style imaginable, transmogrifying the most unlikely sources into fodder for New York@Night improvisation. That eclecticism is not an accident; most musicians attracted to jazz 4 are open-minded by nature and bring with them a panoply of influences. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis Zu "Two Roads, Both Taken"

Inhalt JeffLevenson Two Roads, Both Taken Roland Spiegel The gentleman with the finely-contoured tone Franco Ambrosetti - musician, industrialist, and a story-teller with a serene and refined style Childhood and Adolescence My father • Music • My mother • Toots Thielemans * The revelation • Trumpet for ever • An uphill climb • Boarding school • The first time • P.S. The Sixties - Part One Welcome to Zurich • The Africana • Baroque music and jazz: improvisation • Flavio Ambrosetti All Stars • Zurich by night • University • P.S. The Sixties - Part Two Big festivals • Comblain-la-Tour • Warsaw • Prague • Festival of Bologna and Mingus • Mingus • P.S. • Milan, the Derby and Miles • Villa Pirla • Miles and Herbie • Vienna: the contest • The award ceremony • In California ♦ Doubts persist • P.S. The Sixties - Part Three Basel and graduation at last! • Thoughts and dilemmas • Vita nova-A new life • Graduatuion • Gift and choice • P.S. Bibliografische Informationen http://d-nb.info/1204323941 The Seventies - Part One 63 Two professions and the battle with time • Digressions on dichotomy • Back to Ticino • The Band and the George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band • P. S.: Gianluca and Flavia The Seventies - Part Two 71 PDU, the steady quartet and Umbria Jazz * Trumpet Machine • Sleeping Gipsy • Berliner Jazzfest • Enja and New York City * P.S. The Roaring Eighties 81 C.M.R. • How to manage a lack of time • Advice for all trumpet players, dichotomous or not • The most successful projects of the decade • Heart Bop • Wings • P. S. • Tentets • Movies und Movies Too * The Salami Section and Ravas earful • Third Stream • P.S. The Nineties 99 A whirlwind of events • Sooner or later it happens • Silli • Twenty years of romance • P.S. -

Die Frühen Jahre Des Jazz in Der Schweiz Forum 2017

ling 20 üh 18 Fr ANALOGUE AUDIO SWITZERLAND ASSOCIATION Verein zur Erhaltung und Förderung der analogen Musikwiedergabe Rückblick: Analog-Forum 2017 in Basel Music in the brain – Die Musik spielt im Kopf Die frühen Jahre des Jazz in der Schweiz Forum 2017 Die frühen Jahre des Jazz in der Schweiz Referat von Beat Blaser am Analog-Forum 2017 Text: Urs Mühlemann Der Schweizer Jazzmusiker (Alt- und Baritonsaxophon, u.a. «Interkantonale Blasabfuhr», «Aargauer Saxophonquartett») und Musikjournalist Beat Blaser ist Redaktor für Jazz beim Schweizer Radio (SRF 2), wo er auch die Sendung «Jazz aktuell» moderiert. Er hat uns freundlicherweise die Folien zu seiner Präsentation zur Verfügung gestellt, die als Grundlage für den nachfolgenden Bericht dienten. Ergän- zungen mit weiterführenden Informationen sowie Fotos stammen aus den verschiedensten Internet- Quellen. Begleitet wurde das Referat von verschiedenen Tonbeispielen. Original Dixieland Jazz Band: die erste Jazz-Aufnahme erfolgte 1917 in New York Ankunft mit Verspätung Ernest Ansermet Jazz kam relativ spät in die Schweiz. Weil das Land neutral blieb und nicht am Ersten Weltkrieg teilnahm, Geburtshilfe via Klassische Musik kamen weder US-Bands zu uns, noch ergaben sich Die erste wirkliche Begegnung mit Jazz in der Schweiz Kontakte zu amerikanischen Musikern. Zudem ist die ergab sich durch einen Artikel des Dirigenten Ernest Schweiz ein Binnenland ohne Häfen und weist keine Ansermet in der «Revue Romande» vom 15. Okto- wirklichen Metropolen auf. Es gibt auch keine sprach- ber 1919 über das «Southern Syncopating Orchestra» liche Verwandtschaft; England hatte dadurch einen von Will Marion Cook. Er erkannte «blue notes» («des Vorteil, da die US-Musiker sich eben dort niederlies- tiercés ni majeur ni mineur», ungewohnte Folgen von sen oder dort auftraten. -

Aktuelle Jazzszene Schweiz = La Scène Actuelle Du Jazz En Suisse

Aktuelle Jazzszene Schweiz = La scène actuelle du jazz en Suisse Autor(en): Solothurnmann, Jürg Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Die Schweiz = Suisse = Svizzera = Switzerland : offizielle Reisezeitschrift der Schweiz. Verkehrszentrale, der Schweizerischen Bundesbahnen, Privatbahnen ... [et al.] Band (Jahr): 62 (1989) Heft 5: Jazz : in der Schweiz bewegt er sich = ce qui bouge en Suisse = in Svizzera si muove = how Switzerland got rhythm PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-774159 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Aktuelle Jazzszene Schweiz Von Jürg Solothurnmann Die fünfziger Jahre bedeuteten für die Schweizer Jazzszene einen Anregend für junge Musiker wirkt der Graubündner Saxophonist Neubeginn. -

EFG LUGANO ESTIVAL JAZZ 2019 41Esima Edizione - Piazza Della Riforma

[email protected] EFG LUGANO ESTIVAL JAZZ 2019 41esima edizione - Piazza della Riforma Giovedì 4.7 Marcin Patrzalek “Ho iniziato per caso. La scuola stava finendo e mio padre mi ha iscritto a un corso di chitarra per evitare che mi annoiassi troppo durante le vacanze…”. Così in un’intervista Marcin Patrzslek, il 19enne polacco, giovanissimo e straordinario chitarrista e compositore. Lo scorso anno Marcin ha vinto l’edizione italiana di “Tu si que vales” conquistando il premio di 100mila euro che gli permetterà di continuare a studiare e perfezionare talento per la chitarra acustica. Suona con incredibile virtuosismo la Classica (dalla V Sinfonia di Beethoven ai Capricci di Paganini) ma anche il Flamenco e il Jazz: pagine acustiche che esegue in maniera impeccabile applicando lo stile tradizionale accanto a un gioco percussivo sorprendente, un “tapping” velocissimo e affascinante grazie al quale riesce a sfruttare appieno la tastiera e le corde dello strumento. Marcin si esibisce da solo in apertura della prima serata di Estival, un preludio per l’ingresso dell’Orchestra della Svizzera italiana (OSI) con il suo prestigioso ospite. RAY LEMA Orchestra della Svizzera italiana (OSI) Conductor: Mariano Chiacchiarini feat. Etienne Mbappe Ray Lema Pianista, chitarrista e compositore, Ray Lema è forse fra gli artisti più eclettici e inclassificabili, fra i più conosciuti al mondo, un’icona della musica africana. Una tipologia ideale per il tradizionale e suggestivo incontro con l’OSI a Estival. La sua musica è un insieme di Jazz, Afro-Beat e Classica: tutto ciò che ha accompagnato la sua vita. Compongo al pianoforte, racconta Ray, e un buon compositore impara a sognare al passo sinfonico e a suonare leggendo le partiture.