Use and Abuse of Oral Evidence Roy Hay Introduction People Have Always Been Concerned to Find out About the Past and Have Devise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Battle for the Floodplains

Battle for the Floodplains: An Institutional Analysis of Water Management and Spatial Planning in England Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Karen Michelle Potter September 2012 Abstract Dramatic flood events witnessed from the turn of the century have renewed political attention and, it is believed, created new opportunities for the restoration of functional floodplains to alleviate the impact of flooding on urban development. For centuries, rural and urban landowning interests have dominated floodplains and water management in England, through a ‘hegemonic discourse alliance’ on land use development and flood defence. More recently, the use of structural flood defences has been attributed to the exacerbation of flood risk in towns and cities, and we are warned if water managers proceeded with ‘business as usual’ traditional scenarios, this century is predicted to see increased severe inconveniences at best and human catastrophes at worst. The novel, sustainable and integrated policy response is highly dependent upon the planning system, heavily implicated in the loss of floodplains in the past, in finding the land for restoring functioning floodplains. Planners are urged to take this as a golden opportunity to make homes and businesses safer from flood risk, but also to create an environment with green spaces and richer habitats for wildlife. Despite supportive changes in policy, there are few urban floodplain restoration schemes being implemented in practice in England, we remain entrenched in the engineered flood defence approach and the planner’s response is deemed inadequate. The key question is whether new discourses and policy instruments on sustainable, integrated water management can be put into practice, or whether they will remain ‘lip-service’ and cannot be implemented after all. -

Culture Club Announced Alongside Jessica Mauboy, Dami Im and Paul Kelly for 6Th AACTA Awards Presented by Foxtel

MEDIA RELEASE Strictly embargoed until 12.01am on Tuesday 22 November 2016 Culture Club announced alongside Jessica Mauboy, Dami Im and Paul Kelly for 6th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel In the lead up to Australia’s biggest film and television Awards, the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) has announced that iconic UK pop group Culture Club will be performing at the 6th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel, alongside Australian artists Paul Kelly, Jessica Mauboy and Dami Im like you’ve never seen her before. Culture Club’s performance at the Awards Ceremony will be their only televised performance and will feature the original band line up: singer Boy George, guitarist and keyboardist Roy Hay, bassist Mikey Craig and drummer Jon Moss. Culture Club are returning to Australia for an Encore Tour in mid- December, which will see them perform in some capital cities and several winery shows. Australia’s love affair with Culture Club continues and their June tour saw them sell out shows and perform to rave reviews. Boy George said he was “Thrilled to be coming back to Australia and to be performing at Australia’s biggest celebration of film and television.” The Grammy Award winning group will bring their own unique style and performance to the AACTA Awards. Selling more than 150 million records worldwide, with multiple worldwide number one singles including Do You Really Want to Hurt Me and the BRIT Award-winning Karma Chameleon, Culture Club are one of the true icons of the world music scene. ARIA Award winning actress and Sony Music recording artist Jessica Mauboy will return to perform at the AACTAs four years since her show-stopping performance at the 2nd AACTA Awards, where she also won the AACTA Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in THE SAPPHIRES. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

Book Review Register

BOOK REVIEW REGISTER July 2019 2 Table of Contents 1. Book Review Register for Sporting Traditions 3 2. Review Guidelines for Sporting Traditions 5 3. Sample Book Reviews for Sporting Traditions 7 5. Reviews of Australian Society for Sports History Publications 12 3 Book Review Register for Sporting Traditions The following is a register of books for which reviews are needed. The general policy is to allocate no more than one book at a time per reviewer. This will hopefully improve the turnover time for reviews and potentially broaden the pool of reviewers. Regular updates of the Register will be posted on the Society’s website at http://www.sporthistory.org/. The Book Review Register is arranged in alphabetical order by author surname. Further information provides a link to more details about the book that may assist you in your selection. Link to Additional Author (s) Title Information Adogame, Afe, Watson, N. J. and Parker, Andrew Global Perspectives on Sports and (eds) Christianity, Routledge, London, 2018 Further information Cazaly: The Legend, Slattery Media Allen, Robert Group, Melbourne, 2017 Further information Anderson, Jennifer & Hockey: Challenging Canada's Game, Further information Ellison, Jenny (eds) University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, 2018 A Life in Sport and Other Things: A Memoir, Manchester Metropolitan University Centre for Research into Bale, John Coaching, Crewe, Cheshire, 2013. The Northies’ Saga: Fifty Years of Club Cricket with North Canberra Barrow, Graeme Gungahlin, 2013. Tourism and Cricket: Travels to the Baum, Tom and Boundary, Channel View Publications, Butler, Richard (eds) Bristol, 2014. $24.95 Further information Cold War Games, Echo Publishing, Blutstein, Harry Richmond, 2017. -

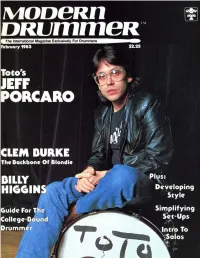

February 1983

VOL. 7 NO. 2 Cover Photo by Rick Malkin FEATURES JEFF PORCARO After having been an in-demand studio drummer for sev- eral years, Jeff Porcaro recently cut back on his studio activities in order to devote more energy to his own band, Toto. Here, Jeff describes the realities of the studio scene and the motivation that led to Toto. by Robyn Flans 8 CLEM BURKE If a group is going to continue past the first couple of albums, it is imperative that each member grow and de- velop. In the case of Blondie, Clem Burke has lived up to the responsibility by exploring his music from a variety of directions, which he discusses in this recent conversation with MD. by Rick Mattingly 12 DRUMS AND EDUCATION Jazz Educators' Roundtable / Choosing a School — And Getting ln / Thoughts On College Auditions by Rick Mattingly and Donald Knaack 16 BILLY HIGGINS The Encyclopedia of Jazz calls Billy Higgins: "A subtle drummer of unflagging swing, as at home with [Ornette] Coleman as with Dexter Gordon." In this MD exclusive, Billy talks about his background, influences and philoso- phies. by Charles M. Bernstein 20 LARRY BLACKMON Soul Inspiration by Scott Fish 24 Photo by Gary Evans Leyton COLUMNS STRICTLY TECHNIQUE EDUCATION Open Roll Exercises PROFILES by Dr. Mike Stephens 76 UNDERSTANDING RHYTHM SHOP TALK Half-Note Triplets Paul Jamieson by Nick Forte 28 RUDIMENTAL SYMPOSIUM by Scott Fish . 36 A Prescription For Accentitus UP AND COMING CONCEPTS by Nancy Clayton 78 Anton Fig Visualizing For Successful Performance by Wayne McLeod 64 by Roy Burns 34 TEACHER'S FORUM Introducing The Drum Solo NEWS ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Harry Marvin 86 Same Old 16ths? UPDATE by John Xepoleas 48 by Robyn Flans 94 INDUSTRY 96 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC EQUIPMENT Developing Your Own Style by Mark Van Dyck 50 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP DEPARTMENTS Pearl Export 052-Pro Drumkit EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 2 ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr. -

Boy George (George O'dowd) (B

Boy George (George O'Dowd) (b. 1961) by Tina Gianoulis Boy George performing Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. in London in 2001. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Photograph by Jessica Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Hansson. Image appears under the Boy George is, like many middle-aged queers, a survivor. And, like many pop icons, Creative Commons Attribution ShareAlike one of the main trials he has had to survive is his own fame. License Version 2.5. The Boy George persona, which came to international attention with the success of the band Culture Club in the early 1980s, threatened to overshadow completely Boy George the performer. However, George's talent, resilience, and genuine affability have seen him through his band's breakup, his own drug addiction, an unexpected solo comeback, and a 1998 reunion with Culture Club. Retaining his sense of style and eclecticism throughout, George has proved he is not merely a stage persona, but also a real original and a gay pioneer. Born in Bexleyheath, a cheerless section of South London, on June 14, 1961, George Alan O'Dowd was the third of six children born to working class Irish parents. His father, a builder and boxing coach, and his mother, who worked in a nursing home, had little attention to spare to give emotional support to their children, especially little George, who showed signs of being "different" from a very early age. He often showed up at church in outlandish hats and platform shoes. Indeed, the eccentric clothes he wore to school got him assigned to a class for incorrigibles. -

Making Waves – the Newsletter of the Contact [email protected] with Any Feedback on the New Sites

makingwaves news from the International Marine Contractors Association issue 47 – May 2008 Putting people first IMCA brings together contractors, training establishments and agency representatives to identify industry needs, discuss training provision and tackle the skills shortage together. Trinity Hall in Aberdeen was the venue from training providers and agencies. for an IMCA seminar dedicated to They covered issues such as the balance training and related issues which took between standardised and bespoke place on 27 February and attracted courses, consistency both between over 75 eager delegates. contractors and between schools, along with the critical role agencies play in The event had been organised by the supplying appropriately trained and HR Specialist Workgroup, under the competent personnel to support the TCPC committee, to facilitate better industry’s work. communication between contractors and training establishments on current Four presentations from training training needs and delivery. establishments in the four technical divisions – diving, marine, offshore survey Roy Hay of Technip, the workgroup’s and ROV – set out the variety of courses chairman, opened the event by outlining on offer and how in each area training this objective. He noted that a primary providers looked to work together with objective was for contractors and industry for the benefit of all. training establishments to work together to identify the ‘log jams’ that were Delegates then split into sector-specific hindering training and retention of workshops to address the practical personnel, such as the difficulties in issues being faced in each part of the getting bed space for trainees offshore industry before reconvening for a final (see page 4 for more on this issue). -

Some Albums Well Worth Buyin; A; Mannequin; Eomance

Fcp 12 Monday, November 21, KZ3 A ft' (O 2 . ri 0 11 New band, The Kydz, t plays diverse music. By Stephanie Zink The Kydz, one of Lincoln's newest bands, consists of four very differentmusicians who got together to create their own unique sound. i v Mary Mullins and Carleen Kreitler were members of the now-defun- ct Dick and Janes. They still wanted to be in a group, if not to perform, then to just play, Kreitler said. They also enlisted drummer Eric Shanks and guitarist. Dan Shoemaker, who have since departed from the group. The Kydz wa3 formed in late June. 6t Kreitler, Shoemaker and Shanks are students at UNL The group's purpose, Kreitler said, is to make people nappy and to have a good time. "Everybody just puts in all they can," Kreitler said. She said it is hard for the band members to coordi- Some albums well worth buyin; with nate what are doing what the ether 4iirv, fc 1 3! m, they TI f George. The flamboyant lead singer is just part of members are doing because they sometimes play Club's overall sound. too fast Culture New music hatnt been hard to come by lately, but Roy Hay's keyboard work is a very strong point on "There are few real musicians (in Lincoln) who has. Many albums that have been released the album, especially on "It's a Miracle." More syn- said. He said Kreitler is one money can really play," Shanks arent worth the vinyl they were printed on, but a thesizer and electronics are used than previously. -

0812 Life.Qxd (Page 1)

THE BUZZ HouseWorks: Wednesday, August 12, 2015 D Health 101: Compiled from H&R staff and They were news service reports National Immunization Herald&Review Aug. 12 birthdays all good ideas Former Sen. Dale Bumpers, D- Awareness Ark., 90; actor George Hamilton, 76; at the Life actress Dana Ivey, 74; actress Jen- nifer Warren, 74; rock singer-musi- Month/Thursday cian Mark Knopfler time/D2 (Dire Straits), 66; actor Jim Beaver, 65; singer Questions or comments regarding this section? Contact Life Editor Jeana Matherly at (217) 421-6974 www.herald-review.com Kid Creole, 65; jazz musician Pat Methe- 30TH ANNIVERSARY ny, 61; actor Sam J. Jones, 61; actor Bruce Hamilton Greenwood, 59; coun- try singer Danny Shirley, 59; pop musi- cian Roy Hay (Culture Club), 54; rapper Sir Mix-A-Lot, 52; actor Peter Krause, 50; actor Brent Sexton, Krause 48; International Ten- nis Hall of Famer Pete Sampras, 44; actor-comedian Sophia Dawson and Dariana Lamb were not the only Vanilla Ice wows the crowd Saturday night on Cameron Carter checks out the competition in the Michael Ian Black, 44; actress Yvette ones screaming as they rode the God of Thunder dur- the Funfest Stage. Baby Mister portion of the Adorable Baby Contest Nicole Brown, 44; actress Rebecca ing the preview for the Decatur Celebration carnival. at the celebration. Gayheart, 44; actor Casey Affleck, 40; rock musician Bill Uechi (Save Ferris), 40; actress Maggie Lawson, 35; actress Dominique Swain, 35; actress Leah Pipes (TV: "The Origi- nals"), 27; actress Imani Hakim, 22. Today in history In 1985, the world's worst single- aircraft disaster occurred as a crip- pled Japan Airlines Boeing 747 on a domestic flight crashed into a moun- tain, killing 520 people. -

Boy George and Culture Club Announce 40-City, 2016 Tour Including Milwaukee

Boy George and Culture Club Announce 40-city, 2016 Tour Including Milwaukee The Iconic Band Comes to the Marcus Center’s Uihlein Hall on Saturday, July 23 at 8:00 pm April 25, 2016 (Milwaukee) – Overwhelming excitement and outstanding reviews caused by Boy George and Culture Club's performances from last year's mini-tour across the U.S, has driven the group to announce their first full tour in more than 12 years spanning 40 cities throughout the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Australia and Asia. Known for dominating the charts worldwide with their classic hits including “Karma Chameleon,” “Do You Really Want To Hurt Me” and “Miss Me Blind,” the iconic band will kick-off their tour on June 6, 2016 at Adelaide Entertainment Centre in Adelaide, Australia. Culture Club is making a stop in Milwaukee at the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts on Saturday, July 23 at 8:00 pm. Tickets go on sale this Friday, April 29 at 12:00 pm at the Marcus Center Box Office. Tickets can be purchased in person at 929 North Water Street, Downtown Milwaukee, by phone at 414-273- 7206, all Ticketmaster outlets and online at Ticketmaster.com or MarcusCenter.org. This performance is being presented by ACG. Throughout Culture Club’s 2015 mini-tour, the band received rave reviews from some of music’s toughest critics: “But if you like to go out, if you like to feel good, if you like to be transported by music, if you’re in search of authenticity in a land inundated by fake. -

Culture Club to Play at the Hanover Theatre This Summer

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Culture Club to Play at The Hanover Theatre This Summer Worcester, Mass. (May 23, 2016) One of the biggest pop bands of the 80s, UK sensation Culture Club is coming to The Hanover Theatre this summer. Join all the members you know and love, including Boy George, Mikey Craig, Roy Hay and Jon Moss, as Culture Club reunites for the first time in over a decade for their North American tour. Culture Club is playing at The Hanover Theatre on August 31 at 8 p.m. Tickets go on sale to members on Thursday, May 26. Tickets go on sale to the public on Friday, May 27. Culture Club is known for selling more than 50 million records worldwide, led by their classic hits “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me,” “Karma Chameleon” and “I’ll Tumble 4 Ya.” Central to the band’s appeal is the front man Boy George, whose cross-dressing and heavy make-up created an image completely unique to the pop scene. The group enjoyed major success in the 90s, racking up seven straight top hits in the United Kingdom and nine top 10 singles in the United States. Culture Club was the first band since The Beatles to achieve three top 10 hits from their debut album on the Billboard chart. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s list of 500 songs that shape rock and roll includes their hit single “Time (Clock of the Heart).” Tickets to Culture Club start at $45. Discounts are available to members of The Hanover Theatre and groups of 10 or more. -

By JULIA and Brad M.Bucklin All Rights Reserved 2019 Alexandra

1 A REQUEM FOR ALLI – Overdose or Murder ? By JULIA and Brad M.Bucklin All rights reserved 2019 Alexandra Hagedorn died of a suspected overdose on January 31, 2007 in the Tokyo Princess Hotel, Encino California. The Coroner s report is effectively the only public record that Alexandra Hagedorn ever existed. Alli, as she was called, was not a prostitute, a Hollywood wanna be, a desperate drug abuser, she was the daughter of a Billionaire business man and the girlfriend of a Rock N Roll icon. Her death went unnoticed in the rush of the world; and while her twenty-three-year-old life was extinguished from the record they could not eliminate the memories of the people who knew her in her final hours. Yet what happened in those final hours is steeped in mystery and involves a cast of characters right out of the movies some of them have produced. It is a story immersed in a culture that has lingered around Hollywood for almost as long as there has been a Hollywood. In the first half of the 20th century during the heyday of the studio system, Hollywood stars were regularly supplied with barbiturates both legal and illegal in order to keep them working through grueling schedules; a pill to get them up and a pill to bring them down. Drugs permeated the business and the town; drug use was even endorsed by the medical profession. Cocaine was praised as a miracle cure and infused in a new drink, Coca-Cola. Heroin was sold to the public by the Bayer company as early as 1898.Perhaps it was the outlawing of 2 drugs that caused the real problems, but it is definitely a fact that many, many actors, artists, musicians succumbed, as Alli did, to the effects of Heroin, cocaine and other drugs that have flooded the Entertainment business.