Boy George (George O'dowd) (B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1; Iya WEEKLY

Platinum Blonde - more than just a pretty -faced rock trio (Page 5) Volume 39 No. 23 February 11, 1984 $1.00 :1;1; iyAWEEKLY . Virgin Canada becomes hotti Toronto: Virgin Records Canada, headed Canac by Bob Muir as President, moves into the You I fifth month flying its own banner and has become one of the hottest labels in the Cultu country. action THE PROMISE CONTINUES.... Contributing to the success of the label by th has been Culture Club with their albums of th4 Basil', Kissing To Be Clever and Colour By Num- bers. Also a major contributor is the break- W. out of the UB40 album, Labour Of Love, first ; boosted by the reggae group's cover of the forth Watch for: old Neil Diamond '60s hit, Red Red Wine. sampl "Over100,000 Colour By Numbers also t albums were shipped in the first ten days band' -the new Images In Vogue video of 1984 alone," said Muir. "The last Ulle40 Tt album only did about 13,000 here. Now, The' albun ... with Labour Of Love, we have the first gold Lust for Love album outside of Europe, and the success ships here is opening doors in the U.S. The record and c; broke in Calgary and Edmonton and started Al -Darkroom's tour (with the Payola$) spreading." Colour By Numbers has just surpassed quintuple platinum status in Canada which Ca] ...Feb. 17-29 represents 500,000 units sold, which took Va. about 16 weeks. The album was boosted and a new remixed 7" and 12" of San Paku by the hit singles Church Of The Poison Toros Mind, now well over gold, and the latest based single, Karma Chameleon, now well over of Ca the platinum mark in less than ten weeks prom This - a newsingle by Ann Mortifee of release. -

Academic Probation

i^i^dnO I Volumaj/Number 23 Tuesday, Fabruary 8, 1983 ^4i UTSA Why Some Students Don't Win Mid-term at College Exams (See Pg. 3) '^..u*"^ UTSA Lady Faculty present Lose 1 Roadrunners Semester Take on No. 3 UT Ideas for Academic Goals Task Force Probation Longhorns Tonight at (See Pg. 4) Convocation Center Purpose of S.R.A. shMs VJill Depends on the Sprlnj us •fi'om fhis of Students Laat Wadnaaday, In a regular aaaalon of our atudant govam mant — tha Studant Rapraaantativa Aaaambly, tha SRA again damonatratad Ita waaknaaaaa. Thaaa waaknessas iMalcally cantar around poor organization, a general lack of purpoaa, and a low commlttaa work level. Tha poor organization of our SRA was damonatratad In tha firal important diacuaalon of tha meeting. Ttw diacuaslon cantered around upcoming alaetlona, and whether or not tha alaetlona for praaant vaeanciaa and regular yearly alaetlona cama under the old or naw SRA eonatltution. Last aummar, tha SRA paaaed a naw con- atltutlon vvtiieh supposedly took effect Iha moment It waa paaaed. Tha difficultiaa which ensued from tha naw constitution waa wtMtlwr or not It waa legal, since it had to ba forwarded to tlie Dean of Studenta office, tha President's office, and even the Board of Regent's office for thair "approval." The raaaon It idid pass and supposedly take effect immediately waa bacauaa aoma of tiM rapraaantativas fait that they didn't need Letters to the Editor anyone's approval on how to run their own government. At tha pra aant aoma rapresantativaa faal tiMt tha new eonatltution stiould lie in affect «vhila others feel that It would ba Illegal. -

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 June 2021 Page 1 of 4

BBC 4 Listings for 5 – 11 June 2021 Page 1 of 4 SATURDAY 05 JUNE 2021 Sarah and Jan are convinced that there is a link between fashion and hip-hop scenes that have fed off historic power Nanna's murder and an unsolved case from 15 years earlier. It is struggles and culture clashes, both between ancient empires and SAT 19:00 How the Celts Saved Britain (b00ktrby) now a race against time to nail the evidence. Pernille and Theis against French colonisers. She traces the story of Leopold Salvation are puzzled as they realise the case is far from closed. Troels is Senghor, a poet who became the father of Senegalese counting on winning the election and is willing to put everything independence and redefined what Africa is. She explores cities Provocative two-part documentary in which Dan Snow blows on the line. with exuberant murals and street culture that respond to the the lid on the traditional Anglo-centric view of history and past, and she meets internationally acclaimed choreographer reveals how the Irish saved Britain from cultural oblivion during Germaine Acogny, griot musician Diabel Cissokho and hip-hop the Dark Ages. SAT 00:45 The Killing (b00zth0c) legend DJ Awadi. Series 1 He follows in the footsteps of Ireland's earliest missionaries as they venture through treacherous barbarian territory to bring Episode 18 SUN 23:00 Searching for Shergar (b0b623r9) literacy and technology to the future nations of Scotland and The story of one of the world's most valuable racehorses, England. Sarah and Jan check out an abandoned warehouse to look for Shergar, who disappeared in 1983 at the height of the Troubles. -

Battle for the Floodplains

Battle for the Floodplains: An Institutional Analysis of Water Management and Spatial Planning in England Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Karen Michelle Potter September 2012 Abstract Dramatic flood events witnessed from the turn of the century have renewed political attention and, it is believed, created new opportunities for the restoration of functional floodplains to alleviate the impact of flooding on urban development. For centuries, rural and urban landowning interests have dominated floodplains and water management in England, through a ‘hegemonic discourse alliance’ on land use development and flood defence. More recently, the use of structural flood defences has been attributed to the exacerbation of flood risk in towns and cities, and we are warned if water managers proceeded with ‘business as usual’ traditional scenarios, this century is predicted to see increased severe inconveniences at best and human catastrophes at worst. The novel, sustainable and integrated policy response is highly dependent upon the planning system, heavily implicated in the loss of floodplains in the past, in finding the land for restoring functioning floodplains. Planners are urged to take this as a golden opportunity to make homes and businesses safer from flood risk, but also to create an environment with green spaces and richer habitats for wildlife. Despite supportive changes in policy, there are few urban floodplain restoration schemes being implemented in practice in England, we remain entrenched in the engineered flood defence approach and the planner’s response is deemed inadequate. The key question is whether new discourses and policy instruments on sustainable, integrated water management can be put into practice, or whether they will remain ‘lip-service’ and cannot be implemented after all. -

Weißer Mann, Was Nun?

Freiburg · Mittwoch, 15. Januar 2020 http://www.badische-zeitung.de/weisser-mann-was-nun-die-tagung-queer-pop-in-freiburg Weißer Mann, was nun? Die Tagung „Queer Pop“ in Freiburg will nicht nur die Grenzen des Geschlechter-Denkens erweitern, sondern stellt dem Denken auch das Tanzen zur Seite F F O O T T O Als die Pet Shop Boys 1984 mit ihrem Al- ordnung als das Selbstverständnis quee- Unis Seminare zu Queer Pop stattgefun- O : : A C N bum „West End Girls“ ihre erfolgreichste rer Popstars wider, das immerzu chan- den, sondern die Party wird mit Perfor- H N R I E S T T T Zeit erlebten, waren sie noch Teil einer giert, sich neu erfindet und starres Scha- mances Studierender eröffnen, die quee- O E P K H O S schwul-lesbischen Subkultur, die sich in R blonen-Denken bewusst durchkreuzt. re Ästhetik auf die Bühne bringen. Dar- C O H L M Codes ausdrückte. Für das Publikum, das L Bei „Queer Pop“ geht es nicht nur um auf, wie auch heterosexuelle Menschen I D T sie an die Spitze der Charts hievte, stand Musik: Queere Strategien finden sich in sich queer inszenieren, darf man ge- ( D P A die geschlechtliche Identität der Musiker allen medialen Bereichen, vom Film über spannt sein, doch weist diese Frage auch ) zumindest nicht im Vordergrund. Anders Literatur und Mode bis zur Kunst und auf einen anderen Umstand hin: Queeres war das bei Boy George und seiner Band Fotografie. „Wir wollen uns mit queerer Denken hat sich von der reinen Auseinan- Culture Club, die etwa zur gleichen Zeit Ästhetik beschäftigen, aber auch aufzei- dersetzung mit Genderrollen hin zu durch ihr androgynes Auftreten zu welt- gen, wie diese inzwischen Diskussionen grundlegenden sozialkritischen Fragen weiten Pop-Ikonen wurden. -

Culture Club Announced Alongside Jessica Mauboy, Dami Im and Paul Kelly for 6Th AACTA Awards Presented by Foxtel

MEDIA RELEASE Strictly embargoed until 12.01am on Tuesday 22 November 2016 Culture Club announced alongside Jessica Mauboy, Dami Im and Paul Kelly for 6th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel In the lead up to Australia’s biggest film and television Awards, the Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts (AACTA) has announced that iconic UK pop group Culture Club will be performing at the 6th AACTA Awards presented by Foxtel, alongside Australian artists Paul Kelly, Jessica Mauboy and Dami Im like you’ve never seen her before. Culture Club’s performance at the Awards Ceremony will be their only televised performance and will feature the original band line up: singer Boy George, guitarist and keyboardist Roy Hay, bassist Mikey Craig and drummer Jon Moss. Culture Club are returning to Australia for an Encore Tour in mid- December, which will see them perform in some capital cities and several winery shows. Australia’s love affair with Culture Club continues and their June tour saw them sell out shows and perform to rave reviews. Boy George said he was “Thrilled to be coming back to Australia and to be performing at Australia’s biggest celebration of film and television.” The Grammy Award winning group will bring their own unique style and performance to the AACTA Awards. Selling more than 150 million records worldwide, with multiple worldwide number one singles including Do You Really Want to Hurt Me and the BRIT Award-winning Karma Chameleon, Culture Club are one of the true icons of the world music scene. ARIA Award winning actress and Sony Music recording artist Jessica Mauboy will return to perform at the AACTAs four years since her show-stopping performance at the 2nd AACTA Awards, where she also won the AACTA Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in THE SAPPHIRES. -

Radiotimes-July1967.Pdf

msmm THE POST Up-to-the-Minute Comment IT is good to know that Twenty. Four Hours is to have regular viewing time. We shall know when to brew the coffee and to settle down, as with Panorama, to up-to- the-minute comment on current affairs. Both programmes do a magnifi- cent job of work, whisking us to all parts of the world and bringing to the studio, at what often seems like a moment's notice, speakers of all shades of opinion to be inter- viewed without fear or favour. A Memorable Occasion One admires the grasp which MANYthanks for the excellent and members of the team have of their timely relay of Die Frau ohne subjects, sombre or gay, and the Schatten from Covent Garden, and impartial, objective, and determined how strange it seems that this examination of controversial, and opera, which surely contains often delicate, matters: with always Strauss's s most glorious music. a glint of humour in the right should be performed there for the place, as with Cliff Michelmore's first time. urbane and pithy postscripts. Also, the clear synopsis by Alan A word of appreciation, too, for Jefferson helped to illuminate the the reporters who do uncomfort- beauty of the story and therefore able things in uncomfortable places the great beauty of the music. in the best tradition of news ser- An occasion to remember for a Whitstabl*. � vice.-J. Wesley Clark, long time. Clive Anderson, Aughton Park. Another Pet Hate Indian Music REFERRING to correspondence on THE Third Programme recital by the irritating bits of business in TV Subbulakshmi prompts me to write, plays, my pet hate is those typists with thanks, and congratulate the in offices and at home who never BBC on its superb broadcasts of use a backing sheet or take a car- Indian music, which I have been bon copy. -

Culture Club Kissing to Be Clever Mp3, Flac, Wma

Culture Club Kissing To Be Clever mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Kissing To Be Clever Country: Hong Kong Released: 1982 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1555 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1338 mb WMA version RAR size: 1628 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 536 Other Formats: MP4 MMF AHX VOX AAC VQF FLAC Tracklist Hide Credits White Boy (Dance Mix) 1 4:41 Engineer [Assistant] – Gordon Milne 2 You Know I'm Not Crazy 3:37 3 I'll Tumble 4 Ya 2:36 4 Take Control 3:11 Love Twist 5 4:21 Featuring – Captain Crucial 6 Boy Boy (I'm The Boy) 3:51 7 I'm Afraid Of Me (Remix) 3:17 8 White Boys Can't Control It 3:44 Do You Really Want To Hurt Me 9 4:24 Vocals [Additional] – Helen Terry Bonus Tracks 10 Love Is Cold 4:24 Murder Rap Trap 11 4:23 Featuring – Captain Crucial 12 Time (Clock Of The Heart) 3:45 13 Romance Beyond The Alphabet 3:49 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Virgin Records Ltd. Published By – EMI Music Publishing Ltd. Engineered At – Red Bus Recording Studio Pressed By – EMI Uden Credits Backing Vocals – Colin Campsie, Denise Spooner, Phil Pickett Bass, Other [Heavy Culture] – Michael Craig Cover, Design, Typography – Jik Graham Drums, Percussion, Drum Programming [Linn Drum] – Jon Moss Guitar, Keyboards, Piano, Sitar [Electric] – Roy Hay Keyboards [Additional] – Phil Pickett Mixed By – Jon Moss, Steve Levine Photography By – Mark Lebon Producer, Engineer – Steve Levine Saxophone, Flute, Harmonica – Nick Payne* Synthesizer [Synclavier Ii], Programmed By [Synclavier Ii] – Keith Miller Vocals – Boy George Vocals [Talkover Dub Star] – Captain Crucial Written-By, Performer – Culture Club Notes All tracks remaster ℗ 2003 Virgin Records Ltd except tracks 3, 5, 9, 11 & 12 digital remaster ℗ 2002 Virgin Records Ltd. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 41 SEPTEMBER 11TH, 2017 Welcome to Copper #41! The title isn't to announce a James Taylor retrospective---sorry to crush your hopes--- but is just what I see in today's weather reports. The Pacific Northwest, where I'm bound for a long-delayed vacation, is up in flames, along with many other parts of the tinder-dry US. Meanwhile, back in my former home of Florida...they've already had nearly two feet of rain, and Hurricane Irma is not even close to the state yet. Stay safe, everyone. I'm really pleased and excited to have Jason Victor Serinus back with us, with the first part of an intensive introduction to art song. Jason brings tremendous knowledge of the field, and provides plenty of recorded examples to listen to, and in the case of videos, watch. There are many stunning performances here, and I hope you enjoy this extraordinary resource. We'll have Part 2 in Copper #42. Dan Schwartz is again in the lead-off spot with the second in his series of articles on encounters–this one, with Phil Lesh and crew; Seth Godin tells us how control is overrated; Richard Murison hears a symphony; Duncan Taylor takes us to Take 1; Roy Hall tells about a close encounter of the art kind; Anne E. Johnson introduces indie artist Anohni; and I worry about audio shows (AGAIN, Leebs??), and conclude my look at Bang & Olufsen. Industry News tells of the sale of audiophile favorite, Conrad-Johnson; Gautam Raja is back with an amazing story that I think you'll really enjoy, all about Carnatic music, overlooked heritage, and the universal appeal of rock music; and Jim Smith takes another warped look at LPs. -

Book Review Register

BOOK REVIEW REGISTER July 2019 2 Table of Contents 1. Book Review Register for Sporting Traditions 3 2. Review Guidelines for Sporting Traditions 5 3. Sample Book Reviews for Sporting Traditions 7 5. Reviews of Australian Society for Sports History Publications 12 3 Book Review Register for Sporting Traditions The following is a register of books for which reviews are needed. The general policy is to allocate no more than one book at a time per reviewer. This will hopefully improve the turnover time for reviews and potentially broaden the pool of reviewers. Regular updates of the Register will be posted on the Society’s website at http://www.sporthistory.org/. The Book Review Register is arranged in alphabetical order by author surname. Further information provides a link to more details about the book that may assist you in your selection. Link to Additional Author (s) Title Information Adogame, Afe, Watson, N. J. and Parker, Andrew Global Perspectives on Sports and (eds) Christianity, Routledge, London, 2018 Further information Cazaly: The Legend, Slattery Media Allen, Robert Group, Melbourne, 2017 Further information Anderson, Jennifer & Hockey: Challenging Canada's Game, Further information Ellison, Jenny (eds) University of Ottawa Press, Ottawa, 2018 A Life in Sport and Other Things: A Memoir, Manchester Metropolitan University Centre for Research into Bale, John Coaching, Crewe, Cheshire, 2013. The Northies’ Saga: Fifty Years of Club Cricket with North Canberra Barrow, Graeme Gungahlin, 2013. Tourism and Cricket: Travels to the Baum, Tom and Boundary, Channel View Publications, Butler, Richard (eds) Bristol, 2014. $24.95 Further information Cold War Games, Echo Publishing, Blutstein, Harry Richmond, 2017. -

Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Glam Rock By Barney Hoskyns There's a new sensation A fabulous creation, A danceable solution To teenage revolution Roxy Music, 1973 1: All the Young Dudes: Dawn of the Teenage Rampage Glamour – a word first used in the 18th Century as a Scottish term connoting "magic" or "enchantment" – has always been a part of pop music. With his mascara and gold suits, Elvis Presley was pure glam. So was Little Richard, with his pencil moustache and towering pompadour hairstyle. The Rolling Stones of the mid-to- late Sixties, swathed in scarves and furs, were unquestionably glam; the group even dressed in drag to push their 1966 single "Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" But it wasn't until 1971 that "glam" as a term became the buzzword for a new teenage subculture that was reacting to the messianic, we-can-change-the-world rhetoric of late Sixties rock. When T. Rex's Marc Bolan sprinkled glitter under his eyes for a TV taping of the group’s "Hot Love," it signaled a revolt into provocative style, an implicit rejection of the music to which stoned older siblings had swayed during the previous decade. "My brother’s back at home with his Beatles and his Stones," Mott the Hoople's Ian Hunter drawled on the anthemic David Bowie song "All the Young Dudes," "we never got it off on that revolution stuff..." As such, glam was a manifestation of pop's cyclical nature, its hedonism and surface show-business fizz offering a pointed contrast to the sometimes po-faced earnestness of the Woodstock era. -

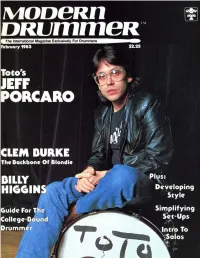

February 1983

VOL. 7 NO. 2 Cover Photo by Rick Malkin FEATURES JEFF PORCARO After having been an in-demand studio drummer for sev- eral years, Jeff Porcaro recently cut back on his studio activities in order to devote more energy to his own band, Toto. Here, Jeff describes the realities of the studio scene and the motivation that led to Toto. by Robyn Flans 8 CLEM BURKE If a group is going to continue past the first couple of albums, it is imperative that each member grow and de- velop. In the case of Blondie, Clem Burke has lived up to the responsibility by exploring his music from a variety of directions, which he discusses in this recent conversation with MD. by Rick Mattingly 12 DRUMS AND EDUCATION Jazz Educators' Roundtable / Choosing a School — And Getting ln / Thoughts On College Auditions by Rick Mattingly and Donald Knaack 16 BILLY HIGGINS The Encyclopedia of Jazz calls Billy Higgins: "A subtle drummer of unflagging swing, as at home with [Ornette] Coleman as with Dexter Gordon." In this MD exclusive, Billy talks about his background, influences and philoso- phies. by Charles M. Bernstein 20 LARRY BLACKMON Soul Inspiration by Scott Fish 24 Photo by Gary Evans Leyton COLUMNS STRICTLY TECHNIQUE EDUCATION Open Roll Exercises PROFILES by Dr. Mike Stephens 76 UNDERSTANDING RHYTHM SHOP TALK Half-Note Triplets Paul Jamieson by Nick Forte 28 RUDIMENTAL SYMPOSIUM by Scott Fish . 36 A Prescription For Accentitus UP AND COMING CONCEPTS by Nancy Clayton 78 Anton Fig Visualizing For Successful Performance by Wayne McLeod 64 by Roy Burns 34 TEACHER'S FORUM Introducing The Drum Solo NEWS ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Harry Marvin 86 Same Old 16ths? UPDATE by John Xepoleas 48 by Robyn Flans 94 INDUSTRY 96 ROCK 'N' JAZZ CLINIC EQUIPMENT Developing Your Own Style by Mark Van Dyck 50 PRODUCT CLOSE-UP DEPARTMENTS Pearl Export 052-Pro Drumkit EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 2 ROCK CHARTS by Bob Saydlowski, Jr.