Glam Rock by Barney Hoskyns 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cic004 Bowie.Pdf

4 Conversations in Creativity Explorations in inspiration Bowie • 2016 creativelancashire.org Creative Lancashire is a service provided by Lancashire County Council through its economic development company - Lancashire County Developments Ltd (LCDL). They support creative and digital businesses and work with all sectors to realise creative potential. Hemingway Design Lemn Sissay In 2011, Creative Lancashire with local design agencies Wash and JP74 launched ‘Conversations in Creativity’ - a network and series of events where creatives from across the crafts, trades and creative disciplines explore how inspiration from Simon Aldred (Cherry Ghost) around the world informs process. Previous events have featured Hemingway Design, Gary Aspden (Adidas), Pete Fowler (Animator & Artist), Donna Wilson (Designer), Cherry Ghost, I am Kloot, Nick Park (Aardman), Lemn Sissay (Poet) and Jeanette Winterson (Author) - hosted by Dave Haslam & John Robb. Donna Wilson Who’s Involved www.wash-design.co.uk www.jp74.co.uk Made You Look www.sourcecreative.co.uk Pete Fowler THE VERY BEST OF BRITANNIA 1. 2. 3. David Bowie:1947-2016 A wave of sadness and loss rippled through the This provides the context for our next creative world after legendary star man David Conversations in Creativity talk at Harris Bowie (David Robert Jones), singer, songwriter Museum as part of the Best of Britannia (BOB) and actor died on 10 January 2016. North 2016 programme, Bowie’s creative process evolved throughout his As a companion piece to the event we’ve 40+ year career, drawing inspirations from the collaborated with artists and designers including obvious to the obscure. Stephen Caton & Howard Marsden at Source Creative, and Andy Walmsley at Wash and artists; 4. -

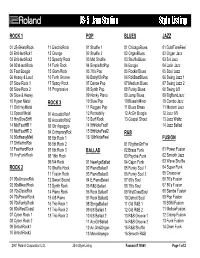

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing

PTSVNWU JS-5 Jam Station Style Listing ROCK 1 POP BLUES JAZZ 01 JS-5HardRock 11 ElectricRock 01 Shuffle 1 01 ChicagoBlues 01 DublTimeFeel 02 BritHardRck1 12 Grunge 02 Shuffle 2 02 OrganBlues 02 Organ Jazz 03 BritHardRck2 13 Speedy Rock 03 Mid Shuffle 03 ShuffleBlues 03 5/4 Jazz 04 80'sHardRock 14 Funk Rock 04 Simple8btPop 04 Boogie 04 Latin Jazz 05 Fast Boogie 15 Glam Rock 05 70's Pop 05 Rockin'Blues 05 Soul Jazz 06 Heavy & Loud 16 Funk Groove 06 Early80'sPop 06 RckBeatBlues 06 Swing Jazz 1 07 Slow Rock 1 17 Spacy Rock 07 Dance Pop 07 Medium Blues 07 Swing Jazz 2 08 Slow Rock 2 18 Progressive 08 Synth Pop 08 Funky Blues 08 Swing 6/8 09 Slow & Heavy 09 Honky Piano 09 Jump Blues 09 BigBandJazz 10 Hyper Metal ROCK 3 10 Slow Pop 10 BluesInMinor 10 Combo Jazz 11 Old HvyMetal 11 Reggae Pop 11 Blues Brass 11 Modern Jazz 12 Speed Metal 01 AcousticRck1 12 Rockabilly 12 AcGtr Boogie 12 Jazz 6/8 13 HvySlowShffl 02 AcousticRck2 13 Surf Rock 13 Gospel Shout 13 Jazz Waltz 14 MidFastHR 1 03 Gtr Arpeggio 14 8thNoteFeel1 14 Jazz Ballad 15 MidFastHR 2 04 CntmpraryRck 15 8thNoteFeel2 R&B 16 80sHeavyMetl 05 8bt Rock 1 16 16thNoteFeel FUSION 17 ShffleHrdRck 06 8bt Rock 2 01 RhythmGtrFnk 18 FastHardRock 07 8bt Rock 3 BALLAD 02 Brass Funk 01 Power Fusion 19 HvyFunkRock 08 16bt Rock 03 Psyche-Funk 02 Smooth Jazz 09 5/4 Rock 01 NewAgeBallad 04 Cajun Funk 03 Wave Shuffle ROCK 2 10 Shuffle Rock 02 PianoBallad1 05 Funky Soul 1 04 Super Funk 11 Fusion Rock 03 PianoBallad2 06 Funky Soul 2 05 Crossover 01 90sGrooveRck 12 Sweet Sound 04 E.PianoBalad 07 60's Soul 06 -

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Dec. 22, 2015 Snd. Tech. Album Arch

SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) Affinity-Affinity S=Trident Studio SOHO, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R=1970 (Vertigo) E=Frank Owen, Robin Geoffrey Cable P=John Anthony SOURCE=Ken Scott, Discogs, Original Album Liner Notes Albion Country Band-Battle of The Field S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Island Studio, St. Peter’s Square, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=1973 (Carthage) E=John Wood P=John Wood SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Albion Dance Band-The Prospect Before Us S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. (PARTIALLY TRACKED. MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Olympic Studio #1 Studio, Barnes, London (PARTIAL TRACKING) R=Mar.1976 Rel. (Harvest) @ Sound Techniques, Olympic: Tracks 2,5,8,9 and 14 E= Victor Gamm !1 SOUND TECHNIQUES RECORDING ARCHIVE (Albums recorded and mixed complete as well as partial mixes and overdubs where noted) P=Ashley Hutchings and Simon Nicol SOURCE: Original Album liner notes/Discogs Alice Cooper-Muscle of Love S=Sunset Sound Recorders Hollywood, CA. Studio #2. (TRACKED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) S=Record Plant, NYC, A&R Studio NY (OVERDUBS AND MIX) R=1973 (Warner Bros) E=Jack Douglas P=Jack Douglas and Jack Richardson SOURCE: Original Album liner notes, Discogs Alquin-The Mountain Queen S= De Lane Lea Studio Wembley, London (TRACKED AND MIXED: SOUND TECHNIQUES A-RANGE) R= 1973 (Polydor) E= Dick Plant P= Derek Lawrence SOURCE: Original Album Liner Notes, Discogs Al Stewart-Zero She Flies S=Sound Techniques Studio Chelsea, London. -

Mott the Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - the Biography Free Download

MOTT THE HOOPLE AND IAN HUNTER: ALL THE YOUNG DUDES - THE BIOGRAPHY FREE DOWNLOAD Campbell Devine | 423 pages | 09 Aug 2007 | Cherry Red Books | 9781901447958 | English | London, United Kingdom Ian Hunter (singer) Jonesy and Coop went and when I finally tracked them down for a full report, their eyes were still ricocheting around like pinballs, all fan-boy struck and gloating more than just a little bit. Hunter and Ronson then parted professionally, reportedly due to Hunter's refusal to deal with Ronson's manager, Tony DeFries. The new lineup toured in lateand the concerts were documented on 's Mott the Hoople Live. No trivia or quizzes yet. Ditto Bender, with a pair of his own with the criminally overlooked and underappreciated Widowmaker not the wanky Dee Snider outfit. Greg Reeves marked it as to-read Nov 29, Jane marked it as to-read Jun 07, Mott The Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - The Biography they were interviewed extensively for the book, following publication both Dale Griffin and Overend Watts disowned the book and were scathing about it and the Mott The Hoople and Ian Hunter: All the Young Dudes - The Biography. An album of the same name was released on Columbia Records in the fall, and it became a hit in the U. Lauren Griffin marked it as to-read Dec 30, Queenonce an opening act for Mott the Hoople, provided backing vocals on one track. Hunter's entry into the music business came after a chance encounter with Colin York and Colin Broom at a Butlin's Holiday Campwhere the trio won a talent competition performing " Blue Moon " on acoustic guitars. -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse http://www.lipulse.com/blog/article/mixed-media-december-online-supp... currently 43°F and mostly cloudy on Long Island search advertise | subscribe | free issue Mixed Media December Online Supplement Published: Wednesday, December 09, 2009 U.K. Music Travelouge Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out and Gimmie Shelter As a followup to our profile of rock photographer Ethan Russell in the November issue, we will now give a little more information on the just-released Rolling Stones projects we discussed with Russell. First up is the reissue of the Rolling Stones album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!. What many consider the best live rock concert album of all time is now available from Abcko in a four-disc box set. Along with the original album there is a disc of five previously unreleased live performances and a DVD of those performances. There is a also a bonus CD of five live tracks from B.B. King and seven from Ike & Tina Turner, who were the opening acts on the tour. There is also a beautiful hardcover book with an essay by Russell, his photographs, fans’ notes and expanded liner notes, along with a lobby card-sized reproduction of the tour poster. Russell’s new book, Let It Bleed (Springboard), is now finally out and it’s a stunning visual look back on the infamous tour and the watershed Altamont concert. Russell doesn’t just provide his historic photos (which would be sufficient), but, like in his previous Dear Mr. Fantasy book, he serves as an insightful eyewitness of the greatest rock tour in history and rock music’s 60’s live Waterloo. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Dee Quits Four Month

11EWS shed press officer Annie Branson, prom- otion man Paul Sargent and regional£40,000 TV Deals Dee quits promotion chief Trish Connolly. Dee was said tbe leaving to concentrate onspend for Polly Brown's Nia net a erhis ownaoctiviies. Meanwhile Lynne Peacock, who hasLeo Sayer LP belated token four monthS been with Magnet for some time, has been promoted, and her new areas ofCHRYSALIS RECORDS is mounting DAVE DEE has left Magnet Recordsresponsibility have been extended toa £40,000 test TV campaign in the after just four months as head of presscover national promotion, marketingGranada area next week to promote Leo and promotion. and press, working with a team report-Sayer's World Radio album - first His departure coincides with a rash ofing directly to her from each of thesereleased in mid -May. redundancies at the label, which has alsoareas. The campaign breaks on July 28 and runs for three weeks. There will be a mix of 60, 20 and ten second spots making a total of 21 spots altogether. If success- Secondary boost for Digance ful, the push will then roll into the INDEPENDENT COAST Records hasa joint promotion with the eating houseCentral TV area. moved into the secondary merchandis-chain running. A 50 -off voucher is Display packs for the album are ing field with a Richard Digance cassetteincluded with the package entitling theavailable from PolyGram free of charge.GOOD LUCK token: Polly Brown designed to be sold through the chain ofpurchaser to a discount on mail -order-Order number is DPLS5. receives a belated silver disc from the roadside Happy Eater cafes, called Mr.ing Backwater. -

SLAP Supporting Local Arts & Performers

Issue 42 SLAP Supporting Local Arts & Performers Welcome to the November issue of SLAP Magazine and another packed issue it is too. If you thought for one minute things might start to go quiet around these parts then think again! We’ve spent some time burning the midnight oil to bring you all the latest goings on from the local arts community including our feature on long established local artist Chris Bourke, as well as amongst others, our very own Katie Foulkes and her debut photography exhibition. Nov 2014 With loads of Theatre news, CD and gig reviews, interviews and previews to the many exciting shows coming up in your area, there’s something within these pages for everyone. We also meet local singer/song writer Tom Forbes, strongly SLAP MAGAZINE tipped for greater things, who also provides our colourful front Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, cover imagery ahead of his latest release ‘Wallflower’. Worcester WR1 2RS I have to mention two sad losses to the music world which Telephone: 01905 26660 certainly took the shine off deadlining on another issue of [email protected] SLAP this October. Former Cream bass player and solo artist For advertising enquiries, please contact: Jack Bruce who was a big influence to many died from Liver [email protected] Failure at the age of 71. And Alvin Stardust who lost his fight EDITORIAL Mark Hogan against Prostrate Cancer at the age of 72. Only last week Alvin Kate Cox - Arts editor was entertaining fans at the Regal Cinema in Evesham. CONTRIBUTORS Andy O’Hare On a more positive note Wilko Johnson declared himself Chris Bennion cured of pancreatic cancer at the Q Awards following surgery Mel Hall earlier this year. -

MUSIC WEEK MARCH 25, 1978 P. D 0 KD N

MUSIC WEEK MARCH 25, 1978 0 D P. n D K JOHNTAVENER ROBERT GORDON and The Whale. Ring o' Records 2320 LINK VVRAY 104. Producer: Michael Bremner. Fresh Fish Special. Private Stock This is Tavcner's fantasy on the PVLP 1038. Producers: Richard Biblical allegory of Jonah and the Gottehrer and Robert Gordon. This Albums of the week Whale, with the London Sinfonietta duo from the States caused apparently playing everything considerable reaction on their recent including the kitchen sink in European tour. Solid rock 'n' roll, passages and mezzo Anna Reynolds with Gordon often sounding like and baritone Raimund Herincx, plus early Elvis. In the world of rock Alvar Lidell delivering interesting guitarists, VVray has become facts about the whale species at the something of a legend with his start of Side 2. Tavener plays organ own distinctive, always loud, I ' . and Hammond organ, and the style. Included on this album is album is an intricate, complex Gordon's latest single, the Bruce *3^ proposition quite likely to interest Springstein tune, Fire. your contemporary classics freaks but no one else. BETHNAL Dangerous Time. Vertigo 9102 020. Marketed by Phonogram. Produced QUANTUM JUMP by Kenny Laguna. One of the belter Quantum Jump. Electric TRIX 1. bands to emerge from IQTT's 'New Barracuda. Electric TRIX 3. Both Wave'. Energetic, liverly rock albums produced by Rupert Hine. centred around the electric violin A Two re-releases from the Cube and lead vocals of George Csapo. , m Electric catalogue. Note that Cube Includes current single We've Gotta Electric product is now available Get Out Of This Place.