The Human Genome Project and Molecular Anthropology Mark Stoneking 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington University Record, April 1, 1993

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Washington University Record Washington University Publications 4-1-1993 Washington University Record, April 1, 1993 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record Recommended Citation "Washington University Record, April 1, 1993" (1993). Washington University Record. Book 615. http://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/record/615 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington University Publications at Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Record by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS iecord Vol. 17 No. 25 April 1,1993 Architecture class teaches universal design, sensitivity Architecture students recently tried experiencing the world from the perspective of people with disabilities. For a few hours, students maneuvered in wheelchairs, wore blindfolds over their eyes or plugs in their ears to try to get a sense of the needs of people with physi- cal impairments. Some students also spent an entire day in wheelchairs. One took the bus to the St. Louis Galleria, another tried to go out to dinner. For Michele Lewis, a graduate stu- dent in the course, just being at home was difficult. "I even had trouble getting into my building, and there are people living there who are in wheelchairs," she said. "The hallways are too skinny, I couldn't reach my toothbrush and the stove is too high. How are you supposed to know when your water is boiling when you can't see it?" This empathic experience is part of a course taught by Mary Ann Lazarus, vice president at Hellmuth, Obata, and Kassabaum (HOK), an international Sophomore Becky Sladky signs up to be a host for April Welcome, an expanded student recruitment program. -

AMPK Against NASH Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) Is Activation Were Elevated in LAKO Mice the Most Severe Form of Non-Alcoholic on NASH-Inducing Diets

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS collected from people representing published the first report of Journal Club all major global populations. mtDNA mutations causing a The most important discovery of disease — Leber’s hereditary optic mtDNA IN THE CROSSROADS OF their work was that the highest neuropathy. As disease- causing EVOLUTION AND DISEASE degree of mtDNA variation was mutations are amenable to natural found among Africans, attesting to selection, how could one consider Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) their anti quity. The other finding the mtDNA to be merely a neutral sequences are currently studied was that although mtDNA from marker? It was this contradiction mainly by three disciplines: across the globe contained African that drew me into studying molecular evolution (including types, Africans had many unique mitochondrial biology and to anthropology), functional mtDNA types. discovering that even common genomics and analyses of genetic These two findings, in addition population variants of mtDNA are disorders. Strangely, these discip- to other data, prompted Cann et al. both subjected to natural selection lines can use the relatively short mtDNA (1987) to propose that the origin and alter the tendency to develop sequence of mtDNA in opposing has been of all current human populations genetic disorders. manners, by attributing to it either considered (at least the maternal lineage) is Dan Mishmar Department of Life Sciences, lack of function, as is the case an excellent likely African. Many criticized in (some) molecular evolution this study, especially because Ben- Gurion University of the Negev, marker for Be’er- Sheva, Israel. studies, or conversely, functional their African samples originated e- mail: [email protected] mainly from Afro-Americans relevance in the aetiology of tracing ancient The author declares no competing interests genetic disorders. -

Recent Human Evolution

A common ancestor at 500 ka? H. heid. in Europe and Africa LCA of Nea. and sapiens? The origin of our species (H. sapiens) TWO origins to explain: 1.The shared (species) features 2. Non-shared (regional/racial) features Origins of modern human behaviour? Complex technology “Houses Networking” Symbolic burials Art Models of modern human origins 1984 1970 1987: Mitochondrial Eve hits the headlines! Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution Nature 325, 31-36 Rebecca L. Cann, Mark Stoneking & Allan C. Wilson (1987) African female ancestor ~200ka The pendulum starts swinging! 2000 1995 1995 1984 1970 The African record H. sapiens: fossils suggest an African origin for the modern pattern ~ 150-200ka? Age ka ~260 ~150? ~160? ~195? >130 Tim White Lieberman Pinnacle Point Howiesonspoort Microliths Klasies Twin Rivers Enakpune Mumba ya Muto Shellfishing Grotta Moscerini Ochre Kapthurin Twin Rivers Klasies Qafzeh Blombos 300 ka 200 150 100 50 0 Taforalt Shell beads Skhul Enakpune Blombos ya Muto Early H. sapiens fossils Omo Kibish Herto “Modern” anatomy and behaviour have deep roots in Africa… ~60 ka: Modern Humans start to leave Africa… ? Out of Africa Mitochondrial DNA Out of Africa Y-chromosome DNA The evolution of regionality (“race”) DNA benetton Natural selection Bottlenecks + Founder Effects Sexual/cultural selection We are all the same (species), but we all look different (individuals, ♀/♂, regions, “races”). Species Individuals (Homo sapiens) large brain Natural Selection body shape high round skull Sexual Selection skin colour small face hair -

Unique Features of Human Skin

Center for Academic Research & Training in Anthropogeny (CARTA) Unique Features of Human Skin Public Symposium ! Friday, October 16, 2015 Chairs: Nina Jablonski, Pennsylvania State University Pascal Gagneux, UC San Diego This CARTA symposium is sponsored by: The G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation ABSTRACTS Skin: A Window into the Evolution of the Human Super-Organism Richard Gallo, UC San Diego All life must establish an external barrier that simultaneously interacts with and defends itself from the outside world. Skin is our most important barrier, and human skin has many functions that are in common with other animals but also unique to our species. General skin functions include sensing danger, regulation of internal temperature, maintaining fluid balance and mounting visual sexual displays. Human life also depends on the capacity of our skin to protect us from specific environmental dangers and pathogens unique to us. The central teachings of the medical specialty of Dermatology have been that health is defined by the capacity of skin to perform all these functions while constantly resisting entry of microbial pathogens. However, a recent revolution in understanding skin biology has revealed that normal skin functions are performed not only by cells of human origin, but also by specialized microbes that have co-evolved with us to live in a mutually beneficial relationship. This presentation will provide an overview of the multiple cell types, both human and microbial, that comprise the human skin super-organism. Understanding this relationship changes how we should think about evolution, gene transfer and the impact of current hygiene and antibiotic therapies. -

Patterns of Human Diversity, Within and Among Continents, Inferred from Biallelic DNA Polymorphisms

Letter Patterns of Human Diversity, within and among Continents, Inferred from Biallelic DNA Polymorphisms Chiara Romualdi,1,2,7 David Balding,3,8 Ivane S. Nasidze,4 Gregory Risch,5 Myles Robichaux,5 Stephen T. Sherry,5 Mark Stoneking,4 Mark A. Batzer,5,6 and Guido Barbujani1,9 1 Department of Biology, University of Ferrara, Ferrara I-44100, Italy; 2 Department of Statistics, University of Padua, Padua I-35121, Italy; 3 Department of Applied Statistics, University of Reading, Reading RG6 6FN, United Kingdom; 4 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, D-04103 Germany; 5 Department of Pathology, Stanley S. Scott Cancer Center, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana 70112, USA; 6 Department of Biological Sciences, Biological Computation and Visualization Center, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA Previous studies have reported that about 85% of human diversity at Short Tandem Repeat (STR) and Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) autosomal loci is due to differences between individuals of the same population, whereas differences among continental groups account for only 10% of the overall genetic variance. These findings conflict with popular notions of distinct and relatively homogeneous human races, and may also call into question the apparent usefulness of ethnic classification in, for example, medical diagnostics. Here, we present new data on 21 Alu insertions in 32 populations. We analyze these data along with three other large, globally dispersed data sets consisting of apparently neutral biallelic nuclear markers, as well as with a -globin data set possibly subject to selection. We confirm the previous results for the autosomal data, and find a higher diversity among continents for Y-chromosome loci. -

The New Science of Human Evolution - Newsweek Technology -

The New Science of Human Evolution - Newsweek Technology - ... http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/17542627/site/newsweek/print/1/dis... MSNBC.com The New Science of Human Evolution The new science of the brain and DNA is rewriting the history of human origins. B y Sh ar on Be gl ey Newsweek March 19, 2007 issue - Unlike teeth and skulls and other bones, hair is no match for the pitiless ravages of weather, geologic upheaval and time. So although skulls from millions of years ago testify to the increase in brain size as one species of human ancestor evolved into the next, and although the architecture of spine and hips shows when our ancestors first stood erect, the fossil record is silent on when they fully lost their body hair and replaced it with clothing. Which makes it fortunate that Mark Stoneking thought of lice. Head lice live in the hair on the head. But body lice, a larger variety, are misnamed: they live in clothing. Head lice, as a species, go back millions of years, while body lice are a more recent arrival. Stoneking, an evolutionary anthropologist, had a hunch that he could calculate when body lice evolved from head lice by comparing the two varieties' DNA, which accumulates changes at a regular rate. (It's like calculating how long it took a typist to produce a document if you know he makes six typos per minute.) That fork in the louse's family tree, he and colleagues at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology concluded, occurred no more than 114,000 years ago. -

Mitochondrial Eve and Y-Chromosome Adam: Who Do Your Genes Come From? 28 July 2010

Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? 28 July 2010. Joe Felsenstein Evening At The Genome Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.1/39 Evolutionary trees from molecular sequences from Amrine-Madsen, H. et al., 2003, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.2/39 My ancestor? Charles the Great born 747 (Charlemagne) about 44 more generations 1850s Cornelia John Maud William Itzhak Jacob 1880s Helen Will Sheimdel Lev 1910s Eleanor Jake 1942 Joe Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.3/39 Crossing over (recombination) Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.4/39 Did someone at General Motors take a biology course? The GMC Hybrid logo. Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.5/39 Chromosome 1, back up one lineage −6 (none) −5 −4 −3 −2 −1 now Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.6/39 The “mitochondrial Eve” study in 1987 Rebecca Cann, Mark Stoneking, and the late Allan Wilson. In 1987 they made a molecular tree of mitochondria from humans. Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.7/39 One female ancestor? of what? When? Where? Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.8/39 The “Out Of Africa” hypothesis Europe Asia (vertical scale is not time or evolutionary change) Africa Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.9/39 “Scientists find Eve” Mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosome Adam: Who do your genes come from? – p.10/39 Who was where when Out Of Africa happened? Africa Asia Europe now 100k H. -

Joint Segregation of Biochemical Loci in Salmonidae

JOINT SEGREGATION OF BIOCHEMICAL LOCI IN SALMONIDAE. 11. LINKAGE ASSOCIATIONS FROM A HYBRIDIZED SALVELINUS GENOME (S. NAMAYCUSH x S. FONTZNALZS) * BERNIE MAY, MARK STONEKING AND JAMES E. WRIGHT, JR. Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 Manuscript received September 11, 1979 Revised copy received April 7, 1980 ABSTRACT The results of more than 300 painvise examinations of biochemical loci for joint segregation in brook trout (Salvelinus fontimlis) and in the hybrid- ized genome of lake trout (S. namaycush) x brook trout are summarized. Nineteen loci have been assigned to the following eight linkage groupings on the basis of nonrandom assortment, including cases of both classical linkage and pseudolinkage: ODH with PMI with PGI-3, PGI-2 with SDH, ADA-I with AGP-2, AAT-(1,2) with AGP-I with MDH-I, MDH-3 with MDH-4, LDH-3 with LDH-4, IDH-3 with ME-2 and GUS with CPK-I. Pseudolinkage (an excess of nonparental progeny types) was observed only for male testcross parents. The results suggest that this phenomenon involves homeologous chromosome arms as evidenced by the de novo association of presumed dupli- cate loci in each case. Classical linkage has not been found for the five pairs of duplicate loci examined in Salvelinus, suggesting that not all of the eight metacentrics in the haploid complement involve fusions of homeologous chromosomes. Females consistently showed a greater degree of recombination. is accepted by most authors that the Salmonidae (trouts, salmons, chars, ':raylings and whitefishes) are the derivatives of a tetraploid lineage. It is clear from extensive inheritance and population studies of biochemical loci that (1) segregation is strictly disomic (BAILEYet al. -

Ancient DNA from Guam and the Peopling of the Pacific

Ancient DNA from Guam and the peopling of INAUGURAL ARTICLE the Pacific Irina Pugacha, Alexander Hübnera,b, Hsiao-chun Hungc, Matthias Meyera, Mike T. Carsond,1, and Mark Stonekinga,1 aDepartment of Evolutionary Genetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, D04103 Leipzig, Germany; bDepartment of Archaeogenetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, D04103 Leipzig, Germany; cDepartment of Archaeology and Natural History, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; and dMicronesian Area Research Center, University of Guam, 96923 Mangilao, Guam This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2020. Contributed by Mark Stoneking, November 12, 2020 (sent for review October 26, 2020; reviewed by Geoffrey K. Chambers, Elizabeth A. Matisoo-Smith, and Glenn R. Summerhayes) Humans reached the Mariana Islands in the western Pacific by by Polynesian ancestors until they ventured into eastern Polynesia ∼3,500 y ago, contemporaneous with or even earlier than the ini- within the past 1,000 y (2, 6). tial peopling of Polynesia. They crossed more than 2,000 km of Where these intrepid voyagers originated, and how they relate open ocean to get there, whereas voyages of similar length did to Polynesians, are open questions. Mariana Islanders are un- not occur anywhere else until more than 2,000 y later. Yet, the usual in many respects when compared with other Micronesians settlement of Polynesia has received far more attention than the and Polynesians. Chamorro, the indigenous language of Guam, settlement of the Marianas. There is uncertainty over both the or- is classified as a Western Malayo-Polynesian language within the igin of the first colonizers of the Marianas (with different lines of evidence suggesting variously the Philippines, Indonesia, New Austronesian language family, along with the languages of ’ Guinea, or the Bismarck Archipelago) as well as what, if any, rela- western Indonesia (the islands west of Wallace s Line) (Fig. -

The Paternal and Maternal Genetic History Of

The paternal and maternal genetic history of Vietnamese populations Enrico Macholdt, Leonardo Arias, Nguyen Thuy Duong, Nguyen Dang Ton, Nguyen Van Phong, Roland Schröder, Brigitte Pakendorf, Nong Van Hai, Mark Stoneking To cite this version: Enrico Macholdt, Leonardo Arias, Nguyen Thuy Duong, Nguyen Dang Ton, Nguyen Van Phong, et al.. The paternal and maternal genetic history of Vietnamese populations. European Journal of Human Genetics, Nature Publishing Group, 2020, 28 (5), pp.636-645. 10.1038/s41431-019-0557-4. hal-02559765 HAL Id: hal-02559765 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02559765 Submitted on 30 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. European Journal of Human Genetics (2020) 28:636–645 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0557-4 ARTICLE The paternal and maternal genetic history of Vietnamese populations 1 1 2 2 2 Enrico Macholdt ● Leonardo Arias ● Nguyen Thuy Duong ● Nguyen Dang Ton ● Nguyen Van Phong ● 1 3 2 1 Roland Schröder ● Brigitte Pakendorf ● Nong Van Hai ● Mark Stoneking Received: 13 June 2019 / Revised: 14 October 2019 / Accepted: 17 November 2019 / Published online: 11 December 2019 © The Author(s) 2019. -

Biographical Memoirs of Henry Harpending

Henry C. Harpending 1944–2016 A Biographical Memoir by Alan R. Rogers ©2018 National Academy of Sciences. Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. HENRY COSAD HARPENDING January 13, 1944–April 3, 2016 Elected to the NAS, 1996 Henry Harpending grew up in the small town of Dundee, New York, where his ancestors had lived since 1811. He finished high school at age 17, graduated from Hamilton College at age 20, and then took his time in Harvard grad- uate school, finishing his Ph.D. at age 28. He is hard to categorize: a population geneticist, but also a demog- rapher, an ethnographer, and a sociobiologist. He made fundamental contributions that continue to shape several disciplines. Henry did a total of 43 months of fieldwork, from 1967 through 1992, in the Kalahari Desert of Botswana and Namibia. He worked first with the Ju/’hoansi (formerly known as the !Kung) and later with the Herero. Many of his By Alan R. Rogers most innovative ideas grew out of these field experiences. As a graduate student in the 1960s, he was part of the Harvard Kalahari Project. He travelled widely across the Kalahari, studying populations of Ju/’hoansi. Some were mobile foragers; others, who lived near cattle posts, were seden- tary. The ecological differences between mobile and sedentary Ju/’hoansi would eventu- ally shape much of Henry’s career. At the time, however, his focus was on their genetics and demography. Population Genetics in the 1970s It was a time of enthusiasm within human population genetics. -

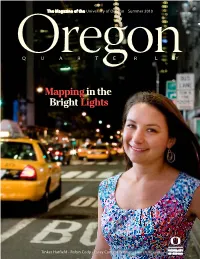

Mapping Inthe Brightlights

The Magazine of the University of Oregon Summer 2010 Mapping in the Bright Lights Tinker Hatfield • Robin Cody • Essay Contest Winner • Lauren Kessler The Magazine of the University of Oregon Summer 2010 • Volume 89 Number 4 24 Tinker, Architect and Designer OregonQuarterly.com Features Departments 24 2 editor’s note tinker 4 Letters by Todd Schwartz Excerpts, Exhibits, A former Duck pole vault record holder, 8 upfront | Tinker Hatfield still enjoys reaching for Explorations, Ephemera Familiar Stranger the sky in his ubiquitous designs for Nike. h uck finn on the colu mbi a 29 by Robin Cody 29 t he terrible teens by Lauren Kessler disappearing act a champion’s take on by Jennifer Meyer athletics and academics In the winning essay of the 2010 Oregon by Andy Drukarev Quarterly Northwest Perspectives Essay Contest, a daughter tries to cope with 14 upfront | News, Notables, the way Alzheimer’s disease changes her Innovations mother. t he great debate: pacifica forum Reason to Believe 32 32 Many cooks, delicious soup vEr HA d ear diary . S day in court N to by Ellen Waterston profile: kathleen karlyn AL W LIE Contesting a speeding ticket gives the a round the Block ; Ju writer a glimpse into the changing culture of Central Oregon. 42 oLd oregon Made for standup Madras Pioneer Madras , 36 t rack-and-field Master HENY t f inding eve, Virgin flies, mA Maps for the times and the origin of clothes SAN by Kimber Williams ; Su Mapping Ideas r t rials of the Links and EYE 36 Erin Aigner mixes data and maps to illus- diamonds r m trate the news in ingenious ways for one of COVer | New York Times cartographer Erin uo alumni calendar the icons of the information industry.