Criminality in Kingston Upon Hull 1846

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOR SALE East Sussex, BN3 2BD 59 Church Road, Hove East Sussex, BN3 2BD

CENTRAL HOVE INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY MIXED USE RETAIL, OFFICE AND RESIDENTIAL BUILDING 59 Church Road, Hove FOR SALE East Sussex, BN3 2BD 59 Church Road, Hove East Sussex, BN3 2BD Key Features • Mixed use freehold opportunity • Available with vacant possession on upper floors • Self-contained ground floor unit • Central Hove location • Rear garden • Offers invited in excess of £675,000 • Mixed use Class E & residential OFFICES IN BRIGHTON, CHICHESTER AND PORTSMOUTH Hove 59 Church Road, Hove East Sussex, BN3 2BD Location & Situation The property is situated in Hove, on the northern side of Church Road, near to Palmeria Square and is located between the seafront and Sussex County Cricket Ground. Numerous bus routes pass along Church Road and there is pay and display parking on the opposite side of the road and side various side roads. Hove railway Station is located to the north just a short walk away. Church Road is a popular retail street in central Hove, home to a high number of cafes, bars and restaurants, as well as various professional and financial services with a mix of office and residential occupiers above. OFFICES IN BRIGHTON, CHICHESTER AND PORTSMOUTH Experian Goad Plan Created: 03/02/2021 50 metres Created By: Flude Commercial For more information on our products and services: Copyright and confidentiality Experian, 2020. © Crown www.experian.co.uk/goad | [email protected] | 0845 601 copyright and database rights 2020. OS 100019885 6011 59 Church Road, Hove East Sussex, BN3 2BD Description & Accommodation The property comprises of a 5 story (including lower ground floor) mid terraced period building. -

Mal Williamson

Embracing entrepreneurship in Hull and East Yorkshire Embracing entrepreneurship 10 2516-8428 842009 ISSN 772516 Business Works Magazine £3.95 Business Works 9 BUSINESSWORKS Autumn 2020 WINDOW SHOPPING Cleaning specialist Andrew Fox on how he grew his one-man operation MAKING A STAND Exhibition designer Rebecca Shipham on the events industry crisis ARCADE FIRED-UP The quirky city centre destination bucking the retail trend Autumn 2020 YOUR TOP 20 Find out who you voted the most inspirational business leaders 010 Style your home with fragrance Candles & Bath Wax Melts & Bath Fragrances Bombs Oil Burners Melts Light & Scent Ltd lives and breathes scents. We are here to reinvigorate you. Our sole purpose is to serve you with the best home fragrance products. www.lightandscent.co.uk [email protected] Light and Scent.indd 1 02/09/2020 20:08 CONTACTS SALES BUSINESSWORKS WELCOME Helen Gowland Managing Director 07854 442741 [email protected] It doesn’t seem like five minutes since I wrote my last editorial, and it has indeed come a bit sooner than usual; with this issue we’re getting our Helen Flintoff schedule back on track after putting the summer 2020 issue on hold for a Commercial Director month due to the lockdown. 0333 0113305 In that time the restrictions have eased considerably, but if I’m honest I [email protected] genuinely don’t know what I am and am not allowed to do any more – how many people can I meet from my household, does it have to be on a Tuesday Joanne Nattress Business Development Manager and do they have to have an R in their name… but I’m fortunate that I can 0333 0117600 still work from home, so I haven’t had to make any agonising decisions. -

Bus Times to Hull Fair Entry to the Museum Is Free

Events & attractions in the City No hassle - just Park and Ride! Hull Fair Friday 10 October 4pm until midnight Saturday 18 October The largest travelling fair in Europe and one of the oldest dating from 1293. Situated on Walton Street car park are stalls filled with the sights and smells of traditional fairground food from hamburgers and hot dogs to candy floss, toffee apples, pomegranates and even hog roast. All can enjoy the fun of the fair with all the most up to date hair raising rides for the thrill-seekers, to the more traditional and children rides. Hull and East Riding Museum Bus Times to Hull Fair Entry to the museum is free. Enter a world where 235 million years of history is brought to life. New From Humber Bridge modern displays take you back to the past. Using original material and monday to friday saturday reconstructed scenes, the displays show just what life was like and how people used to live. first bus runs at 1700 first bus runs at 1300 Opening Times Monday to Saturday 10am until 5pm, Sunday 13.30pm until 4.30pm then up to then up to every 10 mins every 10 mins Streetlife Museum of Transport on demand on demand Entry to the museum is free. until last bus at 2100 until last bus at 2100 Climb aboard at the Streetlife Museum of Transport and enjoy all the sights, sounds and smells of the past. Experience 200 years of transport history as you walk down a 1940’s high street, board a tram or enjoy the pleasures of our carriage ride. -

C TIG Deeds and Historical Papers Relating to 1807-1935 Various Families and Properties in Hull

Hull History Centre: Deeds and historical papers relating to various families and properties in Hull C TIG Deeds and historical papers relating to 1807-1935 various families and properties in Hull Accession number: 06/25 Historical Background: Scott Street, laid out in the late 18th century, was named after the designer, Christopher Scott, a builder, merchant and twice Mayor of Hull, in 1763 and 1776. Custodial history: Records passed by Allen Ticehurt, solicitors of East Grinstead, West Sussex in April 2006 to Hull City Council's Information Governance team, which had been established in 2004. Transferred to the History Centre in May 2006. Description: Deeds, legal and family papers Arrangement : C TIG/1 Deeds, legal and family papers relating to properties on Scott Street 1807-1935 Extent: ½ box Related material: The deeds can also be found at the East Riding Registry of Deeds, which is located at the East Riding of Yorkshire Archives Service at the Treasure House, in Beverley Access conditions: Access will be granted to any accredited reader C TIG/1 Deeds, legal and family papers relating to 1807-1935 properties on Scott Street, Hull 19 items and I bundle C TIG/1/1 Deeds relating to properties on Scott Street, Hull 1807-1935 8 items C TIG/1/1/1 Feoffment of ground in Scott Street, in the Parish of 6 Jul 1807 Sculcoates, County of York i) John Carr, of Dunstan Hill, in the County Palatine of Durham, esquire; Christopher Machell of Beverley in the County of York, esquire and John Alderson of Sculcoates, County of York, doctor of physic -

North Lincolnshire

Archaeological Investigations Project 2003 Post-Determination & Non-Planning Related Projects Yorkshire & Humberside NORTH LINCOLNSHIRE North Lincolnshire 3/1661 (E.68.M002) SE 78700380 DN9 1JJ 46 LOCKWOOD BANK Time Team Big Dig Site Report Bid Dig Site 1845909. 46 Lockwood Bank, Epworth, Doncaster, DN9 1JJ Wilkinson, J Doncaster : Julie Wilkinson, 2003, 13pp, colour pls, figs Work undertaken by: Julie Wilkonson A test pit produced post-medieval pottery and clay pipe stems and a sherd of Anglo-Saxon pottery. [AIP] SMR primary record number:SLS 2725 Archaeological periods represented: EM, PM 3/1662 (E.68.M012) SE 92732234 DN15 9NS 66 WEST END, WINTERINGHAM Report on an Archaeological Watching Brieff Carried out at Plot 3, 66 West End, Winteringham, North Lincolnshire Atkins, C Scunthorpe : Caroline Atkins, 2003, 8pp, figs Work undertaken by: Caroline Atkins Very few finds were made during the period of archaeological supervision, other than fragments of assorted modern building materials, and only one item, a sherd from a bread puncheon, might have suggested activity on the investigated part of the site prior to the twentieth century. [Au(abr)] SMR primary record number:LS 2413 Archaeological periods represented: MO, PM 3/1663 (E.68.M008) SE 88921082 DN15 7AE CHURCH LANE, SCUNTHORPE An Archaeological Watching Brief at Church Lane, Scunthorpe Adamson, N & Atkinson, D Kingston upon Hull : Humber Field Archaeology, 2003, 6pp, colour pls, figs, refs Work undertaken by: Humber Field Archaeology Monitoring of the site strip and excavation of the foundation trench systems revealed the location of a former garden pond. No archaeological features and no residual archaeological material was identified within the upper ground layers. -

THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, 24Th MARCH 1964

186 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE, 24th MARCH 1964 Raymond John Jenkins, of 14 Wilkinson Street North, Elles- John Clifford Chadwick, of 4 Blomfield Road, St. Leomrt mere Port in the county of Chester, and lately residing at on Sea in the county of Sussex, lately residing at Rornw 72 Overpool Road, Ellesmere Port aforesaid, unemployed. Lodge, Ewhurst, Sussex aforesaid, and carrying on busitts in the style of Clifford Chadwick and Co., The Westm William Henry Bolton, residing at 149 Freasley Road, Shard Warehouse, wholesale sundriesman. End, Birmingham 34 in the county of Warwick, Motor Driver, and lately carrying on business from that address William George Sansum, 67 Canons Gate, Little Parndm under the style of " Jack Bolton," mobile grocer and green- Harlow in the county of Essex, a Builder and Decorate grocer. lately carrying on business at 67 Canons Gate, Little Part don, Harlow aforesaid under the style of W. G. Sansin Thoma? Peter Bradley, residing and carrying on business at and Son as a builder and decorator. 76 Timberley Lane, Birmingham 34 in the county of War- wick, Car Body Repairer, formerly carrying on business at Charles Tampion Osborne, 104 Kemball Street, Ipswid, rear of Hawthorn Garage, 62 Chester Road North, Sutton Suffolk, Cleaner, lately carrying on business at 106 Ken- Coldfield in the county of Warwick as a car body repairer ball Street, Ipswich aforesaid, as a general storekeeper. and cellulose sprayer. Donald Clark, of 43 Belgrave Drive in the city and counti A. E. Willis, of Woodside Cottage, The Slough, Studley in of Kingston upon Hull, carrying on business at IDA, 111 the county of Warwick, carrying on business under the Tadman Street, Kingston upon Hull aforesaid, builda style of Willis Electric Co. -

From Partnership to Limited Company 1869-1908

FROM PARTNERSHIP TO LIMITED COMPANY The Story of John Good & Sons Ltd – 175 YEARS OF A FAMILY BUSINESS 12 1869-1908 John Good’s modest ship-owning interests The new business took the name Good An illustration of the obviously stimulated his sons to follow his Brothers & Co, ostensibly because Good & opening of Hull's Albert Dock by the Prince & example, except on a more ambitious scale in Reckitt hardly seemed appropriate for a shipping Princess of Wales in keeping with the emergence of the larger, faster firm, but perhaps the Reckitts wished to mask 1869. (Courtesy of Hull steam ships. In the autumn of 1870 John Good their own involvement. The Carolina was joined Maritime Museum.) noted that Francis and James (later Sir James) in January 1871 by the even larger and more 3 Reckitt, from the Quaker family which had expensive Mont Cenis, 930 tons, 140 bhp and created one of Hull’s most important businesses, costing £30,000 to equip for the sea. The Carolina had approached Joseph and Thomas and asked carried mails to the Cape under Captain MacGarr, whether they would consider a partnership as bringing back cargoes such as cotton seed from steam ship owners. The brothers agreed and, after Alexandria in Egypt, while the Mont Cenis plied at an abortive attempt to acquire a new steamer built first between the UK and India. The life of both in Sunderland, Joseph, with an engineer, travelled vessels was short. On 20 November 1872 the to Holland and bought the 733 ton, 130 bhp Carolina foundered in the North Atlantic on her steamer Carolina, for £16,000. -

Developing Appropriate Strategies for Reducing Inequality in Brighton and Hove

Developing Appropriate Strategies for Reducing Inequality in Brighton and Hove Phase 1 Identifying the challenge: Inequality in Brighton and Hove Phase 1 Final Report December 2007 Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion Ltd (OCSI) EDuce Ltd Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI) 15-17 Middle St Brighton BN1 1AL Tel: 01273 201 345 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ocsi.co.uk EDuce ltd St John’s Innovation Centre Cowley Road Cambridge CB4 0WS Tel: 01223 421 685 Email: [email protected] Web: www.educe.co.uk Developing Appropriate Strategies for Reducing Inequality in Brighton and Hove. Phase 1 Identifying the challenge 2 Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI) and EDuce Ltd Contents Section 1 Executive summary 4 Section 2 Introduction and context 9 Section 3 Key issues coming out of our analysis 14 Appendix A The Brighton and Hove context 54 Appendix B LAA theme: Developing a prosperous and sustainable economy 74 Appendix C LAA theme: Ensuring all our children and young people have the best possible start in life 98 Appendix D LAA theme: A healthy city that cares for vulnerable people and tackles deprivation and injustice 117 Appendix E LAA theme: A safe city that values our unique environment 138 Appendix F Key indicator maps 154 Appendix G Bibliography of sources 155 Appendix H Geography of Brighton and Hove 163 Appendix I Small cities comparator areas 168 Appendix J Acknowledgements 177 Developing Appropriate Strategies for Reducing Inequality in Brighton and Hove. Phase 1 Identifying the challenge 3 Oxford Consultants for -

Highways Agency Project Support Framework A63 Castle Street Improvements, Hull

Highways Agency Project Support Framework A63 Castle Street Improvements, Hull Scheme Assessment Report (Options Selection Stage) Document Reference: W11189/T11/05 Final Rev 6 FEBRUARY 2010 HIGHWAYS AGENCY PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (OPTIONS SELECTION STAGE) FEBRUARY 2010 PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS – HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (W11189/T11/05) A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (OPTIONS SELECTION STAGE) FEBRUARY 2010 Revision Record Revision Ref Date Originator Checked Approved Status 1 14/12/09 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 2 08/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 3 13/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Draft 4 25/01/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final 5 17/02/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final 6 26/02/10 C Riley N Rawcliffe N Rawcliffe Final This report is to be regarded as confidential to our Client and it is intended for their use only and may not be assigned. Consequently and in accordance with current practice, any liability to any third party in respect of the whole or any part of its contents is hereby expressly excluded. Before the report or any part of it is reproduced or referred to in any document, circular or statement and before its contents or the contents of any part of it are disclosed orally to any third party, our written approval as to the form and context of such a publication or disclosure must be obtained. Prepared for: Prepared by: Highways Agency Pell Frischmann Consultants Ltd Major Projects National George House Lateral George Street 8 City Walk Wakefield Leeds WF1 1LY LS11 9AT Tel: 01924 368 145 Fax: 01924 376 643 PROJECT SUPPORT FRAMEWORK A63 CASTLE STREET IMPROVEMENTS - HULL SCHEME ASSESSMENT REPORT (W11189/T11/05) CONTENTS 1. -

Future of Stormwater Lagoon Hull

Future of Stormwater Lagoon Hull LAGOON HULL A1165 N HULL 1km River front development A1033 opportunity areas BALANCED Victoria Dock Consent ready outer A63 harbour development 26-41% REDUCTION IN New four lane highway TRAFFIC ON THE A63 (9.6km) Outer harbour DEFENCE (2km!) 100% The ambitious Lagoon Hull project aims to protect Hessle IMPOUNDED LAGOON (5KM!) Tidal flood protection the city from flooding, while improving transport for at least 100 years connectivity and reinvigorating the local economy. Y £300M U A R Journey time savings Nadine Buddoo reports. E S T E R M B 1,600 100% THROUGH TRAFFIC H U MOVED TO LAGOON ROAD Construction jobs ull is one of the cities estuary – on the southern edge of in the UK which are Hull – compounds its vulnerability £1bn Gross value added most vulnerable cities KEY FACTS to flooding. per annum to coastal flooding “The city is almost trapped by Bridge Humber and rising sea levels. £1.5bn water,” says Hatley. “There has been But the proposed pluvial flooding, which we saw in Lagoon Hull project aims to change Cost of Lagoon 2007, where a massive downpour one or two types of flooding, but Hull is Hall that. into saturated land led to surface vulnerable to all of them. It is a perfect The £1.5bn scheme will involve the water runoff just pooling everywhere storm of all the risk factors.” construction of an 11km causeway in throughout the city before it even got Lagoon Hull aims to deliver a holistic the Humber estuary, creating a non- 11km to the drains. -

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons

Appendix 6 Performance Indicator and CIPFA Data Comparisons BVPI Comparisons Southend-on-Sea vs CPA Environment High Scorers / Nearest Neighbours / Unitaries BV 106: Percentage of new homes built on previously developed land 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Southend-on-Sea 100 100 100 CPA 2002 Environment score 3 or 4 in unitary authorities, by indicator 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Derby 51 63 n/a East Riding of Yorkshire 24.08 16.64 n/a Halton 27.48 49 n/a Hartlepool 40.8 56 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Kingston-upon-Hull 40 36 n/a Luton 99 99.01 n/a Middlesbrough 74.3 61 n/a Nottingham 97 99 n/a Peterborough 79.24 93.66 n/a Plymouth 81.3 94.4 n/a South Gloucestershire 41 44.6 n/a Stockton-on-Tees 33 29.34 n/a Stoke-on-Trent 58.4 61 n/a Telford & Wrekin 54 55.35 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a CIPFA 'Nearest Neighbour' Benchmark Group 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Blackpool 56.8 63 n/a Bournemouth 94 99 n/a Brighton & Hove 99.7 100 n/a Isle of Wight 84 86 n/a Portsmouth 98.6 100 n/a Torbay 39 58.57 n/a Unitaries 2001/02 2002/03 2003/04 Unitary 75th percentile 94 93.7 n/a Unitary Median 70 65 n/a Unitary 25th percentile 41 52.3 n/a Average 66.3 68.7 n/a Source: ODPM website BV 107: Planning cost per head of population. -

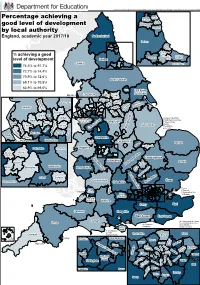

Percentage Achieving a Good Level of Development by Local Authority

Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO © Crown copyright and database right 2018 All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100038433 North Newcastle Tyneside Percentage achieving a upon Tyne South Tyneside good level of development Gateshead Sunderland by local authority England, academic year 2017/18 Northumberland Durham Ha rtle po ol Stockton- on- % achieving a good Tees Redcar & Darlington Middles- Cleveland level of development Durham brough Cumbria North Yorkshire 74.5% to 91.7% 72.7% to 74.4% 70.9% to 72.6% North Yorkshire 69.1% to 70.8% 63.9% to 69.0% York East Riding of Yorkshire Blackpool Lancashire Bradford Leeds 1 w B i t la Calderdale d h s iel c f D k e ke h Calderdale le a ort e a b W N ir u k r sh r ir te ln w r s co n K y a Lin 2 Lancashire e rnsle nc n Ba R o o D S t K h h i e e rk f r e Rochdale fie h r le l a i e d m Bury s h Bolton s Oldham m 1 Kingston Upon Hull Cheshire West st a 2 North East Lincolnshire Wigan a h g 3 Stoke-on-Trent r & Chester E Derbyshire n Sefton Salford e e i K t ir t 4 Derby s h t n Lincolnshire St Helens e Tameside s 5 Nottingham o e o h w d h L r c N 6 Leicester i o e C v s ff n ir e l a h 3 r e ra s p y T M y o b 5 o Warrington Stockport r l e 4 Wirral D Halton Staffordshire Cheshire West & Chester Cheshire East Telford & Wrekin Leicestershire nd Norfolk tla 6 Ru Peterborough Staffordshire Leicestershire Shropshire Wolver- Walsall ire hampton sh W on Cambridgeshire o pt rc Warwickshire am Sandwell es rth Suffolk te o Bedford rs N Warwickshire h n s to e