Rein Taagepera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level)

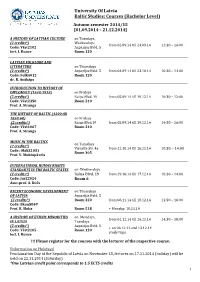

University Of Latvia Baltic Studies: Courses (Bachelor Level) Autumn semester 2014/15 [01.09.2014 – 21.12.2014] A HISTORY OF LATVIAN CULTURE on Tuesdays, (2 credits*) Wednesdays from 02.09.14 till 24.09.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst2102 Azpazijas Bvld. 5 lect. I. Runce Room 120 LATVIAN FOLKLORE AND LITERATURE on Thursdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. 5 from 04.09.14 till 23.10.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: Folk4012 Room 120 dr. R. Auškāps INTRODUCTION TO HISTORY OF DIPLOMACY (1648-1918) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 10:30 – 12:00 Code: Vēst2350 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga THE HISTORY OF BALTIC (1200 till 1850-60) on Fridays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd.19 from 05.09.14 till 19.12.14 14:30 – 16:00 Code: Vēst1067 Room 210 Prof. A. Stranga MUSIC IN THE BALTICS on Tuesdays (2 credits*) Visvalža Str. 4a from 21.10.14 till 16.12.14 10:30. – 14:00 Code : MākZ1031 Room 305 Prof. V. Muktupāvels INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS STANDARTS IN THE BALTIC STATES on Wednesdays (2 credits*) Raiņa Blvd. 19 from 29.10.14 till 17.12.14 10:30 – 14:00 Code: JurZ2024 Room 6 Asoc.prof. A. Kučs RECENT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT on Thursdays OF LATVIA Azpazijas Bvld. 5 (2 credits*) Room 320 from 06.11.14 till 18.12.14 12:30 – 16:00 Code: Ekon5069 Prof. B. Sloka Room 518 + Monday, 10.11.14 A HISTORY OF ETHNIC MINORITIES on Mondays, from 01.12.14 till 16.12.14 14:30 – 18:00 IN LATVIA Tuesdays (2 credits*) Azpazijas Bvld. -

The Right of Self-Determination After Helsinki and Its Significance for the Baltic Nations Boris Meissner

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 13 | Issue 2 1981 The Right of Self-Determination after Helsinki and Its Significance for the Baltic Nations Boris Meissner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Boris Meissner, The Right of Self-Determination after Helsinki and Its Significance for the Baltic Nations, 13 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 375 (1981) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol13/iss2/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. The Right of Self-Determination After Helsinki and its Significance for the Baltic Nations* by Boris Meissnert I. INTRODUCTION 11HE CONFERENCE FOR Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) was concluded on August 1, 1975 with the adoption of a Final Act (the Helsinki Accords) by the 35 participating States in Helsinki.1 This Final Act has been used since then as the basis for Implementation Conferences in Belgrade and Madrid. The Accords were prefaced by a Declaration of Principles in which the right of peoples to self-determina- tion is the Eighth Principle. Its formulation corresponds to the definition of the right of self-determination in Article 1 of the two U.N. Covenants on Human Rights of December 16, 1966 which have also been ratified by most of the Communist nations, including the Soviet Union.2 The international legal nature of the right of self-determination has long been disputed. -

Arend Lijphart and the 'New Institutionalism'

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu March and Olsen (1984: 734) characterize a new institutionalist approach to politics that "emphasizes relative autonomy of political institutions, possibilities for inefficiency in history, and the importance of symbolic action to an understanding of politics." Among the other points they assert to be characteristic of this "new institutionalism" are the recognition that processes may be as important as outcomes (or even more important), and the recognition that preferences are not fixed and exogenous but may change as a function of political learning in a given institutional and historical context. However, in my view, there are three key problems with the March and Olsen synthesis. First, in looking for a common ground of belief among those who use the label "new institutionalism" for their work, March and Olsen are seeking to impose a unity of perspective on a set of figures who actually have little in common. March and Olsen (1984) lump together apples, oranges, and artichokes: neo-Marxists, symbolic interactionists, and learning theorists, all under their new institutionalist umbrella. They recognize that the ideas they ascribe to the new institutionalists are "not all mutually consistent. Indeed some of them seem mutually inconsistent" (March and Olsen, 1984: 738), but they slough over this paradox for the sake of typological neatness. Second, March and Olsen (1984) completely neglect another set of figures, those -

PSC13 Introduction to Comparative Politics Course Description

PSC13 Introduction to Comparative Politics Instructor: Richard S. Conley, PhD Office hours: TBA Email: [email protected] Teaching Assistant: Li Shao Course Description This course introduces students to the discipline of comparative politics, a subfield in political science. Students of comparative politics study politics in countries around the world. Our course will focus on several important themes in the subfield including the science and the art of comparative politics, ideology and culture, political development, democracy and democratization, and the political economy of development. The approach in the class will be global in three senses of the term: 1) it provides broad coverage with select cases in Europe, Asia, North and South America, the Middle East, and Africa, 2) it offers conceptual comprehensiveness, and 3) it promotes critical thinking. Learning Objectives: The general objective of this course is to increase the students knowledge of political realities all aver the world. Students will learn the many ways governments operate and the various ways people behave in political life. By the end of the term students should be able to: accurately describe political life in select countries in all of the world’s geographic regions; show a familiarity with a wide range of substantive issues in comparative politics and be able to discuss them critically; demonstrate mastery of the main theoretical and analytical approaches to the study of comparative politics. Required Text Mark Kesselmen, Joel Krieger, William Joseph (eds.). Introduction to Comparative Politics (6th Edition, 2012). Available as an Electronic Book. ISBN-10: 1111831823; ISBN-13: 978- 1111831820. Other texts will be available as electronic files Course Hours The course has 26 class sessions in total. -

POL 224Y1: Canada in Comparative Perspective Course Outline Fall 2015 & Winter 2016 (Section L5101)

Department of Political Science University of Toronto POL 224Y1: Canada in Comparative Perspective Course Outline Fall 2015 & Winter 2016 (Section L5101) Class Time: Tuesdays, 6{8 PM Class Location: MS 3153 (Medical Sciences Building 3153) Instructor: Prof. Ludovic Rheault Email: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays, 3{5 PM Office Location: Sidney Smith 3005 Course Description This course introduces students to Canadian politics using a comparative approach. It pro- vides essential knowledge about the variety of political regimes around the world, with con- crete examples emphasizing the comparison of Canada with other countries. Topics covered include the evolution of democracies, political institutions, electoral systems, voting, ideology, the role of the state in the economy, as well as contemporary issues such as social policies, representation and inequalities. The objective of the course is twofold. First, the aim is for students to acquire practi- cal knowledge about the functioning of democracies and their implications for society, the Canadian society in particular. Second, the goal is to get acquainted with the core theories of political science. By extension, this implies becoming familiar with the scientific method, from the conception of theoretical arguments to data analysis and empirical testing. By the end of this course, students should have gained considerable expertise about politics and be more confident about their scientific skills. Course Format The course comprises lectures given in class on Tuesdays, combined with tutorials chaired by teaching assistants (TAs) roughly every two weeks. The precise schedule for tutorials will be determined at the beginning of the course. Tutorials provide students with opportunities to participate actively in the discussions undertaken during the lectures, and to prepare for evaluations. -

An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’S Transition from Socialism to Capitalism

De oeconomia ex natione: An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’s Transition from Socialism to Capitalism Thomas Marvin Denson IV Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science Besnik Pula, Committee Chair Courtney I.P. Thomas Charles L. Taylor 2 May 2017 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Estonia, post-Soviet, post-socialist, neoliberalism, nationalism, nationalist economy, soft nativism Copyright © 2017 by Thomas M. Denson IV De oeconomia ex natione: An Examination of the Role of Nationalism in Estonia’s Transition from Socialism to Capitalism Thomas Marvin Denson IV Abstract This thesis explores the role played by nationalism in Estonia’s transition to capitalism in the post-Soviet era and the way it continues to impact the Estonian economy. I hypothesize that nationalism was the key factor in this transition and that nationalism has placed a disproportionate economic burden on the resident ethnic Russians. First, I examine the history of Estonian nationalism. I examine the Estonian nationalist narrative from its beginning during the Livonian Crusade, the founding of Estonian nationalist thought in the late 1800s with a German model of nationalism, the conditions of the Soviet occupation, and the role of song festivals in Estonian nationalism. Second, I give a brief overview of the economic systems of Soviet and post-Soviet Estonia. Finally, I examine the impact of nationalism on the Estonian economy. To do this, I discuss the nature of nationalist economy, the presence of an ethno-national divide between the Estonians and Russians, and the impact of nationalist policies in citizenship, education, property rights, and geographical location. -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Nationwide Threshold of Representation Rein Taagepera *

Electoral Studies 21 (2002) 383–401 www.elsevier.com/locate/electstud Nationwide threshold of representation Rein Taagepera * School of Social Sciences, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA Abstract How large must parties be to achieve minimal representation in a national assembly? The degree of institutional constraints is reflected indirectly by the number of seat-winning parties (n) and more directly by the threshold of representation (T), defined as the vote level at which parties have a 50–50 chance to win their first seat. The existing theoretical threshold formulas use district-level reasoning and therefore overestimate the nationwide threshold. This study extends the theory to the nationwide level. In addition to district magnitude (M), the number of electoral districts and hence assembly size (S) emerge as important variables. When all seats are allocated in M-seat districts, T=75%/[(M+1)(S/M)0.5] and n=(MS)0.25. T and n are connected by T=75%/[n2+(S/n2)]. These theoretical expectation values are tested with 46 dur- able electoral systems. 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Effective thresholds; Number of parties; District and national levels; Small party representation 1. The problem As shown by Duverger (1954), electoral systems affect party systems. In Sartori’s (1976) terminology, electoral systems can be “feeble” or “strong”, meaning that they can be permissive or inhospitable to small parties. How large should parties be, to be entitled to representation in a national assembly? Should 1% of the nationwide votes suffice, or 3 or 5%? And if a certain cutoff level is felt desirable, then how can it be approached through institutional design? One obvious means is to stipulate a nationwide legal threshold, but this has been used relatively rarely. -

Rasma Karklins CV

CURRICULUM VITAE RASMA KARKLINS 2/5/2007 OFFICE ADDRESS HOME ADDRESS University of Illinois at Chicago 6166 N. Sheridan Rd., apt. 12H Department of Political Science (MC276) Chicago, Il., 60660 1007 W. Harrison USA Chicago, Il., 60607 Tel: 312-996-2396 Fax: 312-413-0440 e-mail: [email protected] FIELDS OF SPECIALIZATION Comparative Politics; East European Politics; Politics of USSR and Successor States; Transitions to Democracy; Comparative Public Policy; Corruption in Post-Communist Systems; Protest and Collective Action; Political Participation, Comparative Ethnic Relations; Citizenship and Integration, European Union Neighborhood Policy. ACADEMIC TRAINING 1975, Ph.D. Political Science, The University of Chicago 1971, M.A. International Relations, The University of Chicago 1969 “Diplom-Politologe,” Free University of Berlin, Germany ACADEMIC POSITIONS/GENERAL 1994-to date Professor of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago 1987-94 Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago 1980-87 Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago 1976-77 Adjunct Assistant Professor, Boston University Overseas Graduate Program in International Relations, Italy and Germany 1975-76 Assistant Professor of Political Science, Boston University ACADEMIC POSITIONS/ADMINISTRATIVE 2003-04 Associate Dean, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago 1999-2001 Head, Department of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago 1994-96 Chair, Department of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago 1 AWARDS and PROFESSIONAL DISTINCTIONS 2004-05 Ed Hewett Public Policy Fellow, National Council for Eurasian and East European Research 2002-03 Visiting Member, School of Social Sciences, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, NJ 2002-02 Participant, “Honesty and Trust Project,” Collegium Budapest, Institute for Advanced Study, February 1996 Scholar in Residence, Rockefeller Center, Bellagio, Italy. -

The Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 4 Issue 9 || September. 2015 || PP.30-32 The Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science Nils-Axel Mörner Patron of the Skytte Foundation, Uppsala, Sweden Abstract:Johan Skytte was a true scholar of the 17th century in Sweden. In 1622 he instituted a new professorship in Eloquence and Politics financed by a separate patronage donation. It has survived all through the years and will soon celebrate its 400 years’ anniversary. In 1994, the foundation running the practical/economical parts of the donation founded an international prize: The Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science. This year, the 21st prize goes to Francis Fukuyama. Keywords:Political Science, Johan Skytte, the Johan Skytte Prize in Political Science, Skytte Foundation, Uppsala University. I. JOHAN SKYTTE AND HIS DONATION IN 1622 Johan Skytte (Figure 1) was born in 1577, son of a merchant. Duke Karl, later to become King Karl IX, understood that the young boy was unusually gifted and intelligent, and he paid for his education abroad[1].He staid abroad for 9 years, visiting different universities in Germany, and travelling to France, England and Scotland. In 1598 he took his thesis in Marburg. He was deeply taken by ramism, the philosophy by Petrus Ramus [1, 2]. According to Ramus all sciences were based on the depth and sharpness in intellectual thinking as expressed by eloquence. Eloquence was the base for everything. It could turn and twist the human heart in whatever direction wanted. -

Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001

Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg Wolfgang Zellner/Randolf Oberschmidt/Claus Neukirch (Eds.) Comparative Case Studies on the Effectiveness of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities Margit Sarv Integration by Reframing Legislation: Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001 Working Paper 7 Wolfgang Zellner/Randolf Oberschmidt/Claus Neukirch (Eds.) Comparative Case Studies on the Effectiveness of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities Margit Sarv∗ Integration by Reframing Legislation: Implementation of the Recommendations of the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities to Estonia, 1993-2001 CORE Working Paper 7 Hamburg 2002 ∗ Margit Sarv, M.Phil., studied Political Science at the Central European University in Budapest. Currently Ms. Sarv works as a researcher at the Institute of International and Social Studies in Tallinn. 2 Contents Editors' Preface 5 List of Abbreviations 6 Chapter 1. Introduction 8 Chapter 2. The Legacies of Soviet Rule: A Brief History of Estonian-Russian Relations up to 1991 11 Chapter 3. Estonia after Independence: The Radicalized Period from 1991 to 1994 19 3.1 From Privileges to Statelessness: The Citizenship Issue in Estonia in 1992 19 3.2 Estonia's Law on Citizenship and International Reactions 27 3.3 HCNM Recommendations on the Law on Citizenship of 1992 29 3.4 Language Training - the Double Responsibility Towards Naturalization and Integration 35 3.5 New Restrictions, -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1This study uses ‘Estonian Veterans’ League’ as the most practical translation of the Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Liit (‘Veterans’ League of the Estonian War of Independence’). The popular term for a Veterans’ League member was vaps (plural: vapsid), or vabs, derived from vabadussõjalane (‘War of Independence veteran’). This often appears mistakenly capitalized as VAPS. A term for the Veterans frequently found in historical literature is ‘Freedom Fighters’, the direct translation of the German Freiheitskämpfer. Another unsatisfactory translation which appears in older literature is ‘Liberators’. It should be noted that until 11 August 1933 the organization was formally called Eesti Vabadussõjalaste Keskliit (‘The Estonian War of Independence Veterans’ Central League’). 2 Ernst Nolte, The Three Faces of Fascism (London, 1965), p. 12. 3 Eduard Laaman, Vabadussõjalased diktatuuri teel (Tallinn, 1933); Erakonnad Eestis (Tartu, 1934), pp. 54–62; ‘Põhiseaduse kriisi arenemine 1928–1933’, in Põhiseadus ja Rahvuskogu (Tallinn, 1937), pp. 29–45; Konstantin Päts. Poliitika- ja riigimees (Stockholm, 1949). 4 Märt Raud, Kaks suurt: Jaan Tõnisson, Konstantin Päts ja nende ajastu (Toronto, 1953); Evald Uustalu, The History of Estonian People (London, 1952); Artur Mägi, Das Staatsleben Estlands während seiner Selbständigkeit. I. Das Regierungssystem (Stockholm, 1967). 5 William Tomingas, Vaikiv ajastu Eestis (New York, 1961). 6 Georg von Rauch, The Baltic States: The Years of Independence 1917–1940 (London, 1974); V. Stanley Vardys, ‘The Rise of Authoritarianism in the Baltic States’, in V. Stanley Vardys and Romuald J. Misiunas, eds., The Baltic States in War and Peace (University Park, Pennsylvania, 1978), pp. 65–80; Toivo U. Raun, Estonia and the Estonians (Stanford, 1991); John Hiden and Patrick Salmon, The Baltic Nations and Europe: Estonia, Latvia & Lithuania in the Twentieth Century (London, 1991).