Broccoli, Cauliflower, and Cabbage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Antimicrobial Activity Study of Brassica Oleceracea †

Proceedings Comparative Antimicrobial Activity Study of Brassica oleceracea † Sandeep Waghulde *, Nilofar Abid Khan *, Nilesh Gorde, Mohan Kale, Pravin Naik and Rupali Prashant Yewale Konkan Gyanpeeth Rahul Dharkar College of Pharmacy and Research Institute, Karjat, Dist-Raigad, Pin code 410201, India; [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (R.P.Y.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (N.A.K.) † Presented at the 22nd International Electronic Conference on Synthetic Organic Chemistry, 15 November– 15 December 2018. Available Online: https://sciforum.net/conference/ecsoc-22. Published: 14 November 2018 Abstract: Medicinal plants are in rich source of antimicrobial agents. The present study was carried out to evaluate the antimicrobial effect of plants from the same species as Brassica oleceracea namely, white cabbage and red cabbage. The preliminary phytochemical analysis was tested by using a different extract of these plants for the presence of various secondary metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, glycosides, steroids, carbohydrates, and amino acids. The in vitro antimicrobial activity was screened against clinical isolates viz gram positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, gram negative bacteria Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Extracts found significant inhibition against all the pathogens. Keywords: plant extract; phytochemicals; antibacterial activity; antifungal activity 1. Introduction Despite great progress in the development of medicines, infectious diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites are still a major threat to public health. The impact is mainly observed in developing countries due to relative unavailability of medicines and the emergence of widespread drug resistance [1]. -

Kohlrabi, Be Sure It Your Money Stays Locally and Is Is No Larger Than 2 1/2” in Diameter, Recirculated in Your Community

Selection Why Buy Local? When selecting kohlrabi, be sure it Your money stays locally and is is no larger than 2 1/2” in diameter, recirculated in your community. with the greens still attached. Fresh fruits and vegetables are The greens should be deep green more flavorful, more nutritious all over with no yellow spots. and keeps more of its vitamins and Yellow leaves are an indicator that minerals than processed foods. the kohlrabi is no longer fresh. You are keeping farmers farming, which protects productive farmland from urban sprawl and being developed. What you spend supports the family farms who are your neighbors. Care and Storage Always wash your hands for 20 seconds with warm water and soap before and after preparing produce. Wash all produce before eating, FOR MORE INFORMATION... cutting, or cooking. Contact your local Extension office: Kohlrabi can be kept for up to a month in the refrigerator. Polk County UW-Extension Drying produce with a clean 100 Polk County Plaza, Suite 190 cloth or paper towel will further Balsam Lake, WI 54810 help to reduce bacteria that may (715)485-8600 be present. http://polk.uwex.edu Keep produce and meats away Kohlrabi from each other in the refrigerator. Originally developed by: Jennifer Blazek, UW Extension Polk County, Balsam Lake, WI; Colinabo http://polk.uwex.edu (June, 2014) Uses Try It! Kohlrabi is good steamed, Kohlrabi Sauté barbecued or stir-fried. It can also be used raw by chopping and INGREDIENTS putting into salads, or use grated or 4 Medium kohlrabi diced in a salad. -

Broccoli; the Green Beauty: a Review

A. I. Owis /J. Pharm. Sci. & Res. Vol. 7(9), 2015, 696-703 Broccoli; The Green Beauty: A Review A. I. Owis Department of Pharmacognosy, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef,Egypt Telephone: +202-01202500017 Abstract Context: Plants are nature′s blessing to mankind to make malady free sound life, and assume an essential part to protect our wellbeing. Broccoli - Brassica oleracea L.var. italica Plenk (Brassicaceae) - is considered as a nutritional powerhouse. The present review comprises the phytochemical and therapeutic potential of broccoli. Objective: This aim of this review to collect results obtained from various studies in order to spot more light towards the surprising green world of broccoli. In addition to, a number of recommendations that will help to secure a more sound „proof- of-concept‟ to complete the whole picture providing significant information could be used as a dietary guideline that encourage broccoli consumption for the management of various diseases. Methods: This review has been compiled using references from major databases such as Chemical Abstracts, ScienceDirect, SciFinder, PubMed, Henriette′s Herbal Homepage and Google scholars Databases. Results: An extensive survey of literature revealed that broccoli is a good source of health promoting compounds such as glucosinolates, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids and vitamins. Moreover, broccoli is the kind of nutrient that has so many wonderful applications including gastroprotective, antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, hepatoprotective, cardioprotective, anti-obesity, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities. Conclusion: There are still missing areas need further in-depth investigation such as effect of broccoli on central nervous system. Keywords: biological activities, Brassica oleracea, Brassicaceae, phytochemistry. INTRODUCTION leaves. -

Morphological Characterisation of White Head Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea Var. Capitata Subvar. Alba) Genotypes in Turkey

NewBalkaya Zealand et al.—Morphological Journal of Crop and characterisation Horticultural ofScience, white head2005, cabbage Vol. 33: 333–341 333 0014–0671/05/3304–0333 © The Royal Society of New Zealand 2005 Morphological characterisation of white head cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata subvar. alba) genotypes in Turkey AHMET BALKAYA Keywords cabbage; classification; morphological Department of Horticulture variation; Brassica oleracea; Turkey Faculty of Agriculture University of Ondokuz Mayis Samsun, Turkey INTRODUCTION email: [email protected] Brassica oleracea L. is an important vegetable crop RUHSAR YANMAZ species which includes fully cross-fertile cultivars or Department of Horticulture form groups with widely differing morphological Faculty of Agriculture characteristics (cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, University of Ankara collards, Brussel sprouts, kohlrabi, and kale). His- Ankara, Turkey torical evidence indicates that modern head cabbage email: [email protected] cultivars are descended from wild non-heading brassicas originating from the eastern Mediterranean AYDIN APAYDIN and Asia Minor (Dickson & Wallace 1986). It is HAYATI KAR commonly accepted that the origin of cabbage is the Black Sea Agricultural Research Institute north European countries and the Baltic Sea coast Samsun, Turkey (Monteiro & Lunn 1998), and the Mediterranean region (Vural et al. 2000). Zhukovsky considered that the origin of the white head cabbage was the Van Abstract Crops belonging to the Brassica genus region in Anatolia and that the greatest cabbages of are widely grown in Turkey. Cabbages are one of the the world were grown in this region (Bayraktar 1976; most important Brassica vegetable crops in Turkey. Günay 1984). The aim of this study was to determine similarities In Turkey, there are local cultivars of cabbage (B. -

Ornamental Cabbage and Kale, Brassica Oleracea in the Fall, Chyrsanthemums and Pansies Are the Predominant Plants Offered for Seasonal Color

A Horticulture Information article from the Wisconsin Master Gardener website, posted 3 Sept 2007 Ornamental Cabbage and Kale, Brassica oleracea In the fall, chyrsanthemums and pansies are the predominant plants offered for seasonal color. But another group of cold-tolerant plants without fl owers can help brighten the fall garden when almost ev- erything else is looking tired and ready for winter. Ornamental cabbage and kale are the same species as edible cabbages, broccoli, and caulifl ower (Bras- sica oleracea) but have much fancier and more col- orful foliage than their cousins from the vegetable garden. While these plants are sometimes offered as “fl owering” cabbage and kale, they are grown for their large rosettes of colorful leaves, not the fl owers. These plants are very showy and come in a variety of colors, ranging from white to pinks, purples or reds. Even though they are technically all kales (kale does not produce a head; instead, it produces leaves in a tight rosette), by convention those types with deeply- cut, curly, frilly or ruffl ed leaves are called ornamen- Ornamental kale makes a dramatic massed planting. tal kale, while the ones with broad, fl at leaves often edged in a contrasting color are called ornamental cabbage. The plants grow about a foot wide and 15” tall. Ornamental cabbages and kales do not tolerate summer heat, and plants set out in spring will likely have bolted or declined in appearance, so it is necessary to either start from seed in mid-summer or purchase trans- plants for a good fall show. -

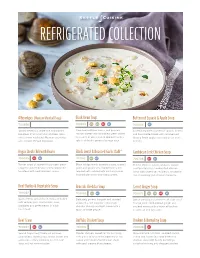

KC Refrigerated Product List 10.1.19.Indd

Created 3.11.09 One Color White REFRIGERATEDWhite: 0C 0M 0Y 0K COLLECTION Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Black Bean Soup Butternut Squash & Apple Soup 700856 700820 VN VG DF GF 700056 GF Savory meatballs, white rice and vibrant Slow-cooked black beans, red peppers, A blend of puréed butternut squash, onions tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken stock roasted sweet corn and diced green chilies and handcrafted stock with caramelized infused with traditional Mexican aromatics in a purée of vine-ripened tomatoes with a Granny Smith apples and a pinch of fresh and a touch of fresh lime juice. splash of fresh-squeezed orange juice. nutmeg. Angus Steak Chili with Beans Black Lentil & Roasted Garlic Dahl* Caribbean Jerk Chicken Soup 700095 DF GF 701762 VG GF 700708 DF GF Tender strips of seared Angus beef, green Black beluga lentils, sautéed onions, roasted Tender chicken, sweet potatoes, carrots peppers and red beans in slow-simmered garlic and ginger slow-simmered in a rich and tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken tomatoes with Southwestern spices. tomato broth, infused with warming spices, stock with white rice, red beans, traditional finished with butter and heavy cream. jerk seasoning and a hint of molasses. Beef Barley & Vegetable Soup Broccoli Cheddar Soup Carrot Ginger Soup 700023 700063 VG GF 700071 VN VG DF GF Seared strips of lean beef and pearl barley Delicately puréed broccoli and sautéed Sweet carrots puréed with fresh-squeezed with red peppers, mushrooms, peas, onions in a rich blend of extra sharp orange juice, hand-peeled ginger and tomatoes and green beans in a rich cheddar cheese and light cream with a sautéed onions with a touch of toasted beef stock. -

How to Grow Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea) Cabbage Varieties Come in a Spectrum of Colors, from Light Green to Dark Purple

How to Grow Cabbage (Brassica oleracea) Cabbage varieties come in a spectrum of colors, from light green to dark purple. The scientific name of cabbage is Brassica oleracea, a species that also includes broccoli, cauliflower, kale, and Brussels sprouts. Time of Planting: Sow cabbage seeds indoors 4-6 weeks before transplanting seedlings outdoors. Transplant cabbage seedlings outdoors just before the last frost. Spacing Requirements: Sow seeds ¼ inch deep. Space cabbages at least 24-36 inches apart in even spacing or 12-14 inches apart in rows spaced 36-44 inches apart. Time to Germination: 7-12 days. Special Considerations: When growing for seed, increase spacing to 18-24 inches apart in rows that are at least 36 inches apart. Staking is recommended. Common Pests and Diseases (and how to manage): Cabbage can suffer from a number of pests and diseases including flea beetles, cabbage moths, aphids, leaf miner bugs, slugs, and black rot. Early season insect pests, such as flea beetles, can be deterred by growing transplants underneath row cover. Harvest (when and how): Cut the head at the base of the plant with a harvesting knife or pruning shears as soon as the cabbage head feels solid. Trim off the loose outer leaves and store heads in a cool place. Eating: Raw cabbage can be used in fresh salads like coleslaw. It can also be enjoyed roasted, braised, stewed, and stir fried. Cabbage is often fermented to make sauerkraut and kimchi. Storing: Cabbage will keep for about four months at a temperature between 32-40 degrees F and a relative humidity of 80-90%. -

Broccoli in a Salad

North Carolina Healthy Serving Ideas • Dice and toss raw broccoli in a salad. • Pour lemon juice or sprinkle lowfat parmesan cheese over steamed broccoli to add and vary flavor. • For a healthy snack, chop raw broccoli into pieces and serve with a fat free vegetable dip. • Add broccoli and other vegetables to soups, pastas, omelets, and casseroles. STEPS TO HEALTH Home Grown Facts The North Carolina Harvest of Zesty Asian Chicken Salad • Broccoli was first grown in Italy and the Month featured vegetable is Makes 4 servings. 1 cup per serving. Prep time: 20 minutes called brocco, which means branch or arm. Ingredients: • 3 boneless, skinless chicken • The name broccoli is plural and refers breasts, cooked and chilled to the numerous flower-like shoots that • 3 green onions, sliced form the head of the plant. • 1½ cups small broccoli florets broccoli • 2 medium carrots, peeled and cut • Broccoli is a cool-season crop, closely into strips related to cabbage, cauliflower, kale, • 1 red bell pepper, cut into strips and mustard. • 2 cups shredded cabbage • 1/2 cup fat free Asian or sesame • In North Carolina, broccoli can be seed salad dressing grown in the spring or the fall. In the • 1/4 cup 100% orange juice spring, broccoli grows in the coast • 1/4 cup chopped fresh cilantro plains, piedmont, or mountain regions of NC. While in the fall, broccoli Directions: 1. Cut chicken breasts into small only grows in the coastal plains and Health and Learning Success strips. Place in a medium bowl piedmont regions of NC. Go Hand-in-Hand with onions, broccoli, carrots, bell • Because it is very easy to grow, broccoli peppers, and cabbage. -

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: the Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture by Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Depa

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: The Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture By Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Department University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 03/01/2016 Approved: _______________________ Karen Auerbach: Advisor _______________________ Chad Bryant: Advisor Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 4 Chapter 1 12 Preparation: The Making of American Jewish Food Culture Chapter 2 31 Consumption: The Impact of Migration on Holocaust Survivor Food Culture Chapter 3 48 Interpretation: The Impact of the Holocaust on American-Jewish Food Culture Conclusion 66 2 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my correspondents, Jay Ipson, Esther Lederman, and Kaja Finkler. Without each of your willingness to invite me into your homes and share your stories, this thesis would not have been possible. Kaja, I thank you especially for your continued support and guidance. Next, I want to give a shout-out to my family and friends, especially my fellow thesis writers, who listened to me talk about my thesis constantly and without a doubt saw the bulk of my negative stress reactions. Thank you all for being such a great support system. It is my hope that at least one of you will read this- here’s looking at you, Mom. Third, I would like to thank Professor Waterhouse for sticking with me throughout this entire process. I could not have done this without your constant kind words and encouragement (though I could have done without your negative commentary about Billy Joel). Thank you for making this possible. Finally, I extend the largest thank you to my wonderful thesis advisors, Professor Karen Auerbach and Professor Chad Bryant. -

KOHLRABI and CABBAGE SALAD with MAPLE LEMON DRESSING Ingredients 4 Medium Bulbs Kohlrabi 3 Cups Shredded Cabbage ¼ Cup Dried Cr

KOHLRABI AND CABBAGE SALAD WITH MAPLE LEMON DRESSING Ingredients 3 tbsp pure maple syrup 4 medium bulbs kohlrabi Zest of 1 lemon 3 cups shredded cabbage Juice of 2 lemons ¼ cup dried cranberries 1 garlic clove, minced ¼ cup sunflower seeds ¼ tsp kosher salt 1/3 tsp freshly ground ¼ cup coarsely chopped fresh dill ¼ cup extra virgin olive oil black pepper DIRECTIONS 1. Using a sharp knife, remove long stems & greens from kohlrabi 2. Using a peeler, trim away the thick green skin until you reach the light green part that is free of tough fibers. Shred on the medium holes of a box greater or in a food processor fitted with the shredder disk. 3. Combine the kohlrabi, cabbage, cranberries, sunflower seeds, and dill in a large serving bowl. In a small jar with a tight-fitting lid, combine the olive oil, maple syrup, lemon zest, lemon juice, garlic, salt, and pepper. 4. Shake to thoroughly combine. Pour the dressing over the salad and toss to coat well. Let sit for about 20 minutes before serving. NUTRITION INFORMATION Per serving: 195 calories, 12g fat, 21.8g carbs, 5.6g fiber, 14.4g sugars,3.4g protein, 126.2mg sodium Recipe & photo courtesy of: The Kitchn RDA: 0% Vitamin A, 33%Vitamin C, 3% Calcium, 4% Iron KOHLRABI AND CABBAGE SALAD WITH MAPLE LEMON DRESSING Ingredients 3 tbsp pure maple syrup 4 medium bulbs kohlrabi Zest of 1 lemon 3 cups shredded cabbage Juice of 2 lemons ¼ cup dried cranberries 1 garlic clove, minced ¼ cup sunflower seeds ¼ tsp kosher salt ¼ cup coarsely chopped fresh dill 1/3 tsp freshly ground black ¼ cup extra virgin olive oil pepper DIRECTIONS 1. -

Sterols, Triglycerides and Essential Fatty Acid Constituents of Brassica Oleracea Varieties, Brassica Juncea and Raphanus Sativus

Available online www.jocpr.com Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, 2013, 5(12):1237-1243 ISSN : 0975-7384 Research Article CODEN(USA) : JCPRC5 Sterols, triglycerides and essential fatty acid constituents of Brassica oleracea varieties, Brassica juncea and Raphanus sativus Consolacion Y. Ragasa 1*, Vincent Antonio S. Ng 2, Oscar B. Torres 2, Nicole Samantha Y. Sevilla 2, Kim Valerie M. Uy 2, Ma. Carmen S. Tan 2, Marissa G. Noel 2 and Chien-Chang Shen 3 1Chemistry Department, De La Salle University Science & Technology Complex Leandro V. Locsin Campus, Biñan City, Laguna, Philippines 2Chemistry Department De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 3National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine, 155-1, Li-Nong St., Sec. 2, Taipei 112, Taiwan _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT The dichloromethane extracts of the leaves of Brassica oleracea var capitata f. rubra L (red cabbage) and Brassica oleracea L (green/white cabbage) and the stem of Brassica oleracea L var. italic (broccoli) afforded β-sitosterol ( 1) and unsaturated triglycerides ( 2). The red cabbage also afforded stigmasterol ( 3), while the green/white cabbage and broccoli stem also yielded the essential fatty acid, linoleic acid ( 4). Brassica juncea (mustard) leaves and Raphanus sativus (radish) roots afforded 1, and the essential fatty acids 4 and α-linolenic acid ( 6). Mustard leaves also yielded trilinolenin ( 5), lutein ( 7) and β-carotene ( 8), while radish roots also afforded -

Cabbage English

North Carolina Healthy Serving Ideas • Cabbage can be steamed, baked, or stuffed as well as eaten raw. • Add raw cabbage to salads like coleslaw or tossed salads. • Serve cooked and seasoned cabbage with meats like beef, chicken, and low-fat sausages. • Other vegetables to pair with cabbage include potatoes, leeks, onions, and carrots. • Substitute cabbage for lettuce in sandwiches and tacos. www.fns.usda.gov STEPS TO HEALTH Home Grown Facts The North Carolina Harvest of Rainbow Coleslaw • Cabbage is grown in most NC counties the Month featured vegetable is Makes 12 servings. 1/2 cup per because it can grow in a variety of soil serving. types. Counties with the most cabbage Prep time: 15 minutes grown are in Pasquotank, Columbus, Ingredients: Robeson, Alleghany, and Ashe counties • 2 cups thinly sliced red cabbage in North Carolina. Cabbage grows • 2 cups thinly sliced green cabbage from March through May and August • 1/2 cup chopped yellow or red through December in NC with peak bell pepper harvest in May and December. • 1/2 cup shredded carrots cabbage • The word cabbage derives from the • 1/2 cup chopped red onion French word caboche meaning “head.” • 1/2 cup fat free mayonnaise there are more than 400 cabbage • 1 tablespoon red wine vinegar varieties but most common are the • 1/4 teaspoon celery seed green, red, purple, and savoy varieties. (optional) GREEN • 1/2 cup lowfat Cheddar cheese, • Cabbage is a cruciferous vegetable. CABBAGE cubed Other vegetables in this family include bok choy, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, Directions: cauliflower, collard greens, kale, Swiss 1.