Broccoli; the Green Beauty: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

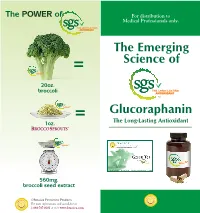

Glucoraphanin the Emerging Science Of

For distribution to Medical Professionals only. The Emerging Science of Glucoraphanin The Long-Lasting Antioxidant ©Brassica Protection Products For more information, call us toll-free at 1-866-747-0001 or visit www.brassica.com Cancer Carcinogen Detoxification Potential to detoxify carcinogens. An elevated level of In 1992, scientists at Johns Hopkins University School hepatitis virus and environmental toxins results in a very of Medicine identified sulforaphane (SF) as a naturally high prevalence of liver cancer in a rural area of China. occurring compound in broccoli that produces long- Scientists from Johns Hopkins University and Qidong lasting antioxidant and detoxification activity and Liver Cancer Institute performed a clinical test to assess appeared to be responsible for the epidemiological whether broccoli sprouts influenced the body’s abilities findings that diets rich in broccoli and cruciferous vegetables were correlated with lower levels of cancer. to detoxify carcinogens. In a single-blinded placebo- These scientists subsequently determined that the controlled trial, 100 test and 100 control subjects drank compound present in the broccoli plant was the a water extract of 3-day-old broccoli sprouts or a placebo glucosinolate precursor of sulforaphane—known as daily over a period of two weeks. The broccoli sprouts glucoraphanin (GR) and available as . group showed a significant decrease in aflatoxin-DNA adduct (a biomarker of DNA damage) levels with increas- In 1997, this research group demonstrated that glucoraphanin ing levels of broccoli sprout consumption. The change content of mature broccoli was highly variable. Further, there is in these biomarkers signals an enhanced detoxification no way for consumers to detect this variability and know whether (neutralization) of carcinogens from the human body they are getting high-concentration broccoli or not. -

Broccoli (Brassica Oleracea L

foods Article Broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica) Sprouts as the Potential Food Source for Bioactive Properties: A Comprehensive Study on In Vitro Disease Models Thanh Ninh Le, Hong Quang Luong , Hsin-Ping Li, Chiu-Hsia Chiu and Pao-Chuan Hsieh * Department of Food Science, National Pingtung University of Science and Technology, Pingtung 91207, Taiwan; [email protected] (T.N.L.); [email protected] (H.Q.L.); [email protected] (H.-P.L.); [email protected] (C.-H.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-08-7740240 Received: 14 October 2019; Accepted: 23 October 2019; Published: 30 October 2019 Abstract: Broccoli sprouts are an excellent source of health-promoting phytochemicals such as vitamins, glucosinolates, and phenolics. The study aimed to investigate in vitro antioxidant, antiproliferative, apoptotic, and antibacterial activities of broccoli sprouts. Five-day-old sprouts extracted by 70% ethanol showed significant antioxidant activities, analyzed to be 68.8 µmol Trolox equivalent (TE)/g dry weight by 2,20-azino-bis-3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic (ABTS) assay, 91% scavenging by 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay, 1.81 absorbance by reducing power assay, and high phenolic contents by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Thereafter, sprout extract indicated considerable antiproliferative activities towards A549 (lung carcinoma cells), HepG2 (hepatocellular carcinoma cells), and Caco-2 (colorectal adenocarcinoma cells) using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, with IC50 values of 0.117, 0.168 and 0.189 mg/mL for 48 h, respectively. Furthermore, flow cytometry confirmed that Caco-2 cells underwent apoptosis by an increase of cell percentage in subG1 phase to 31.3%, and a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential to 19.3% after 48 h of treatment. -

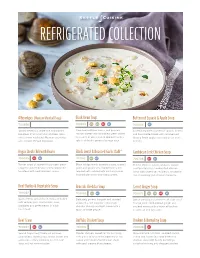

KC Refrigerated Product List 10.1.19.Indd

Created 3.11.09 One Color White REFRIGERATEDWhite: 0C 0M 0Y 0K COLLECTION Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Black Bean Soup Butternut Squash & Apple Soup 700856 700820 VN VG DF GF 700056 GF Savory meatballs, white rice and vibrant Slow-cooked black beans, red peppers, A blend of puréed butternut squash, onions tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken stock roasted sweet corn and diced green chilies and handcrafted stock with caramelized infused with traditional Mexican aromatics in a purée of vine-ripened tomatoes with a Granny Smith apples and a pinch of fresh and a touch of fresh lime juice. splash of fresh-squeezed orange juice. nutmeg. Angus Steak Chili with Beans Black Lentil & Roasted Garlic Dahl* Caribbean Jerk Chicken Soup 700095 DF GF 701762 VG GF 700708 DF GF Tender strips of seared Angus beef, green Black beluga lentils, sautéed onions, roasted Tender chicken, sweet potatoes, carrots peppers and red beans in slow-simmered garlic and ginger slow-simmered in a rich and tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken tomatoes with Southwestern spices. tomato broth, infused with warming spices, stock with white rice, red beans, traditional finished with butter and heavy cream. jerk seasoning and a hint of molasses. Beef Barley & Vegetable Soup Broccoli Cheddar Soup Carrot Ginger Soup 700023 700063 VG GF 700071 VN VG DF GF Seared strips of lean beef and pearl barley Delicately puréed broccoli and sautéed Sweet carrots puréed with fresh-squeezed with red peppers, mushrooms, peas, onions in a rich blend of extra sharp orange juice, hand-peeled ginger and tomatoes and green beans in a rich cheddar cheese and light cream with a sautéed onions with a touch of toasted beef stock. -

Does Selenium Fortification of Kale and Kohlrabi Sprouts Change

Does selenium fortification of kale and kohlrabi sprouts change significantly their biochemical and cytotoxic properties? Pawel Zagrodzki, Pawel Paśko, Agnieszka Galanty, Malgorzata Tyszka-Czochara, Renata Wietecha-Posluszny, Pol Rubió, Henryk Bartoń, Ewelina Prochownik, Bożena Muszyńska, Katarzyna Sulkowska-Ziaja, et al. To cite this version: Pawel Zagrodzki, Pawel Paśko, Agnieszka Galanty, Malgorzata Tyszka-Czochara, Renata Wietecha- Posluszny, et al.. Does selenium fortification of kale and kohlrabi sprouts change significantly their biochemical and cytotoxic properties?. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology, Elsevier, 2020, 59, pp.126466. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126466. hal-03133477 HAL Id: hal-03133477 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03133477 Submitted on 17 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Does selenium fortification of kale and kohlrabi sprouts change significantly their biochemical and cytotoxic properties? Paweł Zagrodzkia Paweł Paśkoa Agnieszka Galanty bMałgorzataTyszka-Czocharaa Renata Wietecha- Posłusznyc -

Concentrated Broccoli Seed Extract

Concentrated Broccoli Seed Extract Clinical Applications The 3rd Opinion Inc. Distributed by: P. • Provides Concentrated Glucoraphanin from Broccoli Seed Extract O. Box 10 • Supports Healthy Cell-Life Cycles* • Supports Phase II Detoxification Enzymes* • Supports Extended Antioxidant Activity* • Supports the Body’s Normal Response to Inflammation* ™ SGS broccoli seed extract is obtained using a patented process to extract glucoraphanin (also known as sulforaphane Chattanooga, OK 7352 glucosinolate or “sgs”) from its most concentrated cruciferous source—broccoli seeds. Glucoraphanin is enzymatically 1-800-431-7902 converted to the extensively researched isothiocyanate known as sulforaphane (SFN). Research suggests that SFN supports long-lasting antioxidant activity and the production of detoxification enzymes. It also extends support to the immune, nervous, and cardiovascular systems, addressing the maintenance of good health throughout adult life. Concentrated Broccoli Seed Extract provides 30 mg of glucoraphanin per capsule and Concentrated Broccoli Seed Extract ES provides 100 mg of glucoraphanin per capsule.* 8 All 3rd Opinion Inc. Formulas Meet or Exceed cGMP Quality Standards Discussion Glucoraphanin (also known as sulforaphane glucosinolate or “sgs”) is a naturally occurring phytochemical found in cruciferous vegetables Broccoli Seed Extract Concentrated and in Concentrated Broccoli Seed Extract formulas. Glucoraphanin, which is heat stable and water soluble, is metabolized in the body to the biologically active isothiocyanate sulforaphane (SFN). Scientists at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine isolated sulforaphane in 1992 and identified glucoraphanin as its precursor. Since their discovery, over 500 scientific studies have been conducted on SFN and glucoraphanin, documenting their positive effects on antioxidant activity, detoxification, cellular metabolism, and cell-life regulation.[1-3] Glucoraphanin and SFN appear to be the “missing link” that correlates a diet rich in cruciferous vegetables (from the Brassicaceae family) with good health. -

Differential Effects of Low Light Intensity on Broccoli Microgreens Growth and Phytochemicals

agronomy Article Differential Effects of Low Light Intensity on Broccoli Microgreens Growth and Phytochemicals Meifang Gao , Rui He, Rui Shi, Yiting Zhang, Shiwei Song , Wei Su and Houcheng Liu * College of Horticulture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China; [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (R.H.); [email protected] (R.S.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (W.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-020-85-280-464 Abstract: To produce high-quality broccoli microgreens, suitable light intensity for growth and phytochemical contents of broccoli microgreens in an artificial light plant factory were studied. Broccoli microgreens were irradiated under different photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD): 30, 50, 70 and 90 µmol·m−2·s−1 with red: green: blue = 1:1:1 light-emitting diodes (LEDs). The broccoli microgreens grown under 50 µmol·m−2·s−1 had the highest fresh weight, dry weight, and moisture content, while the phytochemical contents were the lowest. With increasing light intensity, the chlorophyll content increased, whereas the carotenoid content decreased. The contents of soluble protein, soluble sugar, free amino acid, flavonoid, vitamin C, and glucosinolates except for progoitrin in broccoli microgreens were higher under 70 µmol·m−2·s−1. Overall, 50 µmol·m−2·s−1 was the optimal light intensity for enhancement of growth of broccoli microgreens, while 70 µmol·m−2·s−1 was more feasible for improving the phytochemicals of broccoli microgreens in an artificial light plant factory. -

Broccoli in a Salad

North Carolina Healthy Serving Ideas • Dice and toss raw broccoli in a salad. • Pour lemon juice or sprinkle lowfat parmesan cheese over steamed broccoli to add and vary flavor. • For a healthy snack, chop raw broccoli into pieces and serve with a fat free vegetable dip. • Add broccoli and other vegetables to soups, pastas, omelets, and casseroles. STEPS TO HEALTH Home Grown Facts The North Carolina Harvest of Zesty Asian Chicken Salad • Broccoli was first grown in Italy and the Month featured vegetable is Makes 4 servings. 1 cup per serving. Prep time: 20 minutes called brocco, which means branch or arm. Ingredients: • 3 boneless, skinless chicken • The name broccoli is plural and refers breasts, cooked and chilled to the numerous flower-like shoots that • 3 green onions, sliced form the head of the plant. • 1½ cups small broccoli florets broccoli • 2 medium carrots, peeled and cut • Broccoli is a cool-season crop, closely into strips related to cabbage, cauliflower, kale, • 1 red bell pepper, cut into strips and mustard. • 2 cups shredded cabbage • 1/2 cup fat free Asian or sesame • In North Carolina, broccoli can be seed salad dressing grown in the spring or the fall. In the • 1/4 cup 100% orange juice spring, broccoli grows in the coast • 1/4 cup chopped fresh cilantro plains, piedmont, or mountain regions of NC. While in the fall, broccoli Directions: 1. Cut chicken breasts into small only grows in the coastal plains and Health and Learning Success strips. Place in a medium bowl piedmont regions of NC. Go Hand-in-Hand with onions, broccoli, carrots, bell • Because it is very easy to grow, broccoli peppers, and cabbage. -

NEAT Broccoli Fact Sheet

SY 17 February NEAT Broccoli Fact Sheet Overview: Broccoli was developed from leafy Brassica forms, commonly known as "Calabrese broccoli," found in the northeastern Mediterranean and southern Europe. It can be produced commercially throughout Georgia, but proper scheduling must be followed due to its preference for cooler temperatures and mildly acidic soil needs. Bravo, Green Duke, Premium Crop, Green Hornet, Green Comet and Gem grow best in our state. Fun Fact!! Broccoli is part of the cabbage family. Varieties: Sprouting Broccoli: Most common in the US Broccolini: Cross between broccoli and kale. Broccoflower: Cross between broccoli and cauliflower. Broccoli Sprouts Nutrition: Broccoli is high in fiber, folate, Vitamin C, A, and K. One cup of cooked broccoli has a mere 40 calories of energy, 4g fiber, 90% of the daily value (DV) of Vitamin A and 230% DV vitamin C. Broccoli, especially broccoli sprouts, are a very good source of sulforaphane (sul-for-a-fain), which some studies have suggested may reduce cancer risk. This compound may also help ward off heart problems by reducing inflammation and plaque buildup in arteries as seen in atherosclerosis. Sources: http://panend7.lightsky.net/sites/default/files/SNAC/SNAC_English_newsletter/broccoli_newsletter2.pdf http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.cfm?number=C764 http://www.cdc.gov/features/heartmonth/ http://healthfinder.gov/nho/februarytoolkit.aspx SY 17 February NEAT American Heart Health Month Heart Disease Heart disease is the leading cause of death for both men and women; every 1 in 4 deaths are caused by heart disease. Heart disease can be prevented through adopting a healthy lifestyle with exercise and healthy eating. -

Extract of Broccoli Sprouts May Protect Against Bladder Cancer 28 February 2008

Extract of broccoli sprouts may protect against bladder cancer 28 February 2008 A concentrated extract of freeze dried broccoli humans. It is possible that ITC doses much lower sprouts cut development of bladder tumors in an than those given to the rats in this study may be animal model by more than half, according to a adequate for bladder cancer prevention,” he said. report in the March 1 issue of Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Zhang and his colleagues tested the ability of the Research. concentrate to prevent bladder tumors in five groups of rats. The first group acted as a control, This finding reinforces human epidemiologic while the second group was given only the broccoli studies that have suggested that eating cruciferous extract to test for safety. The remaining three vegetables like broccoli is associated with reduced groups were given a chemical, N-butyl- risk for bladder cancer, according to the study’s N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine (BBN) in drinking senior investigator, Yuesheng Zhang, MD, PhD, water, which induces bladder cancer. Two of these professor of oncology at Roswell Park Cancer groups were given the broccoli extract in diet, Institute. “Although this is an animal study, it beginning two weeks before the carcinogenic provides potent evidence that eating vegetables is chemical was delivered. beneficial in bladder cancer prevention,” he said. In the control group and the group given only the There is strong evidence that the protective action extract, no tumors developed, and there was no of cruciferous vegetables derives at least in part toxicity from the extract in the rats. -

Increasing Antioxidant Content of Broccoli Sprouts Using Essential Oils During Cold Storage

Agriculture (Poľnohospodárstvo), 62, 2016 (3): 111−126 DOI: 10.1515/agri-2016-0012 Original paper INCREASING ANTIOXIDANT CONTENT OF BROCCOLI SPROUTS USING ESSENTIAL OILS DURING COLD STORAGE AML A. EL-AWADY*1, WESAM I. A. SABER2, NABIL M. ABDEL HAMID3 AND HANAA A. HASSAN4 1Department of Vegetable Postharvest and Handling Research, Horticulture Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt 2Microbial Activity Unit, Microbiology Department, Soils, Water and Environment Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt 3Biochemistry Department, Pharmacy College, Kafrelsheikh University, Egypt 4Department of Zoology, Division of Physiology, Faculty of Science, Mansoura University, Mansoura, Egypt AML A. EL-AWADY – WESAMI I.A. SABER – NABIL M. ABDEL HAMID – HANAA A. HASSAN: Increasing antioxidant content of broccoli sprouts using essential oils during cold storage. Agriculture (Poľnohospodárstvo), vol. 62, 2016, no. 3, pp. 111–126. Broccoli sprouts are natural functional foods for cancer prevention because of their high content of glucosinolate and antioxidant. Sprouts and mature broccoli are of potential importance in devising chemoprotective strategies in humans.The aim of the investigation was to study the effect of essential oils on broccoli seed germination, increase their antioxidant content and determine the glucosinolate concentration and other phytochemical parameters in 3-day -old sprouts during cold storage at 4°C and 95% RH for 15 days. The results showed that all treatments of essential oils increased germination index, seed germination percentage, seedling length, seedling vigour index, yield and the antioxidant content of broccoli sprout and reduced the microbial load compared to the control. Fortunately, the co- liform bacteria was not detected in all treatments. Different essential oils of fennel, caraway, basil, thyme and sage were tested. -

Brassica Spp.) – 151

II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) – 151 Chapter 3. Brassica crops (Brassica spp.) This chapter deals with the biology of Brassica species which comprise oilseed rape, turnip rape, mustards, cabbages and other oilseed crops. The chapter contains information for use during the risk/safety regulatory assessment of genetically engineered varieties intended to be grown in the environment (biosafety). It includes elements of taxonomy for a range of Brassica species, their centres of origin and distribution, reproductive biology, genetics, hybridisation and introgression, crop production, interactions with other organisms, pests and pathogens, breeding methods and biotechnological developments, and an annex on common pathogens and pests. The OECD gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Dr. R.K. Downey (Canada), the primary author, without whom this chapter could not have been written. The chapter was prepared by the OECD Working Group on the Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology, with Canada as the lead country. It updates and completes the original publication on the biology of Brassica napus issued in 1997, and was initially issued in December 2012. Data from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and FAOSTAT have been updated. SAFETY ASSESSMENT OF TRANSGENIC ORGANISMS: OECD CONSENSUS DOCUMENTS, VOLUME 5 © OECD 2016 152 – II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) Introduction The plants within the family Brassicaceae constitute one of the world’s most economically important plant groups. They range from noxious weeds to leaf and root vegetables to oilseed and condiment crops. The cole vegetables are perhaps the best known group. Indeed, the Brassica vegetables are a dietary staple in every part of the world with the possible exception of the tropics. -

Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley

Special Report 1064 January 2006 S 105 .E55 no. 1064 Jan 2006 Copy 2 Uutcros sing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley DOES NOT CIRCULATE Oregon State University Received on: 06-28-06 Oregon State I Extension Special report UNIVERSITY Service t1t41 I yt!r_.4.3 a Oregon State University Extension Service Special Report 1064 January 2006 Outcrossing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley James R. Myers Oregon State University Outcrossing Potential for Brassica Species and Implications for Vegetable Crucifer Seed Crops of Growing Oilseed Brassicas in the Willamette Valley James R. Myers Summary The oilseed mustards known as canola or rapeseed (Brassica napus and B. rapa) are the same species as some vegetable crucifers and are so closely related to others that interspecific and intergeneric crossing can occur. Intraspecific crosses (within the same species) readily occur among the following: • B. napus canola with rutabaga and Siberian kale • B. rapa canola with Chinese cabbage, Chinese mustard, pai-tsai, broccoli raab, and turnip Interspecific crosses (between different species) can occur among the following: • Occur readily: B. napus canola with Chinese cabbage, Chinese mustard, pai-tsai, broccoli raab, and turnip • Occur more rarely: B. napus or B. rapa canola with the B. oleracea cole crops (cabbage, kohlrabi, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, cauliflower, collards, and kale) Intergeneric crosses (between species of different genera) are possible with varying degrees of probability: • B. napus or B. rapa canola with wild and cultivated radish (Raphanus raphanis- trum and R.