Book Review: Filming the Decline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations In

Capturing the Void: The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations in Documentary Films on September 11, 2001 Jodye D. Whitesell Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of Film Studies Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Peterson October 24, 2012 Committee Members: Dr. Jennifer Peterson, Film Studies Dr. Melinda Barlow, Film Studies Dr. Carole McGranahan, Anthropology Table of Contents: Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Part I: The Progression of Documentary Film Production………………………………… 9 Part II: September 11, 2001….…………………………………………………………….. 15 Part III: The Immediate Role of the Media………………………………………………... 18 Part IV: Collective Memories and the Media,,,……………………………………………. 25 Part V: The Turn Towards Documentary…………………………………….……………. 34 (1) Providing a Historical Record…………………………………….……………. 36 (2) Challenging the Official Story…………………………………………………. 53 (3) Memorializing the Fallen………………………………………………………. 61 (4) Recovering from the Trauma…………………………………………………... 68 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 79 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………... 83 2 Abstract: Documentary films have long occupied a privileged role among audiences as the purveyors of truth, offering viewers accurate reproductions of reality. While this classification is debatable, the role of documentaries as vehicles for collective memory is vital to the societal reconstructions of historical events, a connection that must be understood in order to properly assign meaning to the them. This thesis examines this relationship, focusing specifically on the documentaries produced related to trauma (in this case the September 11 attacks on the United States) as a means to enhance understanding of the role these films play in the lives and memories of their collective audiences. Of the massive collection of 9/11 documentaries produced since 2001, twenty-three were chosen for analysis based on national significance, role as a representative of a category (e.g. -

The Controversy Over Climate Change in the Public Sphere

THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN (Under the Direction of Edward Panetta) ABSTRACT The scientific consensus on climate change is not recognized by the public. This is due to many related factors, including the Bush administration’s science policy, the reporting of the controversy by the media, the public’s understanding of science as dissent, and the differing standards of argumentation in science and the public sphere. Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was produced in part as a response to the acceptance of climate dissent by the Bush administration and achieved a rupture of the public sphere by bringing the technical issue forward for public deliberation. The rupture has been sustained by dissenters through the use of argument strategies designed to foster controversy at the expense of deliberation. This makes it incumbent upon rhetorical scholars to theorize the closure of controversy and policymakers to recognize that science will not always have the answers. INDEX WORDS: Al Gore, Argument fields, Argumentation, An Inconvenient Truth, Climate change, Climategate, Controversy, Public sphere, Technical sphere THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN B.A., The University of Wyoming, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 William Mosley-Jensen All Rights Reserved THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN Major Professor: Edward Panetta Committee: Thomas Lessl Roger Stahl Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people that made this project possible through their unwavering support and love. -

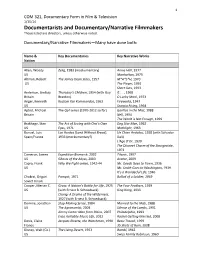

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Professor Daniel A. Nathan "These Days, Sports May Be What Americans AM 234, American Sports/American Culture Talk About Best

Professor Daniel A. Nathan "These days, sports may be what Americans AM 234, American Sports/American Culture talk about best. With the most knowledge. The TLC 301, WF 10:10-11:30 AM most passion. The most humor. The most Office: TLC 300 (580-5023) distance. The most capacity for a cheerful Office Hours: WF, 2:00-3:30 & by appt. change ofmind. When we meet someone for E-mail: [email protected] the first time, it's no accident that sport becomes the subject so often and so quickly. Yes it's an easy, superficial topic-if we want it to be. But talking about sports has also become one of our best ways ofprobing people, sounding their depth, listening for resonances, judging their values." -Thomas Boswell, sports columnist "Sport is a mirror. Sport is life. Through sport we might know ourselves." -David Guterson, writer Course Description & Objectives This course examines the history of American sports and some aspects of the contemporary athletic landscape as a way to consider cultural values. Sports fans beware: this is not a course in sports trivia, nor is it intended to glamorize the games we watch and play. Rather, we will attempt to situate American sports historically and culturally, paying close attention to issues of commercialization, race/ethnicity, gender, and class, among other subjects, such as globalization and fandom. Employing an interdisciplinary approach that makes use ofprimary documents, history, journalism, economics, anthropology, sociology, and film, we will examine recurrent cultural values expressed via American sports and iconic athletes. This course is not intended as a comprehensive survey of American sports. -

Southeastern Ohio's Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil

They Fought the War Together: Southeastern Ohio’s Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil War A Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gregory R. Jones December, 2013 Dissertation written by Gregory R. Jones B.A., Geneva College, 2005 M.A., Western Carolina University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Dr. Leonne M. Hudson, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Bradley Keefer, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Members Dr. John Jameson Dr. David Purcell Dr. Willie Harrell Accepted by Dr. Kenneth Bindas, Chair, Department of History Dr. Raymond A. Craig, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................iv Introduction..........................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: War Fever is On: The Fight to Define Patriotism............................................26 Chapter 2: “Wars and Rumors of War:” Southeastern Ohio’s Correspondence on Combat...............................................................................................................................60 Chapter 3: The “Thunderbolt” Strikes Southeastern Ohio: Hardships and Morgan’s Raid....................................................................................................................................95 Chapter 4: “Traitors at Home”: -

Documentary Movies

Libraries DOCUMENTARY MOVIES The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 10 Days that Unexpectedly Changed America DVD-2043 56 Up DVD-8322 180 DVD-3999 60's DVD-0410 1-800-India: Importing a White-Collar Economy DVD-3263 7 Up/7 Plus Seven DVD-1056 1930s (Discs 1-3) DVD-5348 Discs 1 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green DVD-8778 1930s (Discs 4-5) DVD-5348 Discs 4 70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green c.2 DVD-8778 c.2 1964 DVD-7724 9/11 c.2 DVD-0056 c.2 1968 with Tom Brokaw DVD-5235 9500 Liberty DVD-8572 1983 Riegelman's Closing/2008 Update DVD-7715 Abandoned: The Betrayal of America's Immigrants DVD-5835 20 Years Old in the Middle East DVD-6111 Abolitionists DVD-7362 DVD-4941 Aboriginal Architecture: Living Architecture DVD-3261 21 Up DVD-1061 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House Divided DVD-0001 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 Absent from the Academy DVD-8351 24 City DVD-9072 Absolutely Positive DVD-8796 24 Hours 24 Million Meals: Feeding New York DVD-8157 Absolutely Positive c.2 DVD-8796 c.2 28 Up DVD-1066 Accidental Hero: Room 408 DVD-5980 3 Times Divorced DVD-5100 Act of Killing DVD-4434 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Addicted to Plastic DVD-8168 35 Up DVD-1072 Addiction DVD-2884 4 Little Girls DVD-0051 Address DVD-8002 42 Up DVD-1079 Adonis Factor DVD-2607 49 Up DVD-1913 Adventure of English DVD-5957 500 Nations DVD-0778 Advertising and the End of the World DVD-1460 -

From De-Ba'athification to Daesh: Analyzing the Consequences Of

From De-Ba’athification to Daesh: Analyzing the Consequences of U.S. Policy in Iraq C. J. Dijkstra S1357298 Supervisor: Dr. T. Nalbantian August 2017 Leiden University Faculty of Humanities MA Middle-Eastern Studies: Modern Middle-Eastern Studies Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts 2 Table of contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 State of the field ....................................................................................................................... 6 Pattern of organization ............................................................................................................ 8 Theoretical framework .......................................................................................................... 10 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter 1 – Ottomans and Ba’athists: Historical context of Iraq ................................................. 12 1.1 A brief history of Iraq .......................................................................................................... 12 The Ottoman Empire ............................................................................................................. 12 The British Mandate era ........................................................................................................ 14 Iraq from 1979-2003 ............................................................................................................ -

12Th & Delaware

12th & Delaware DIRECTORS: Rachel Grady, Heidi Ewing U.S.A., 2009, 90 min., color On an unassuming corner in Fort Pierce, Florida, it’s easy to miss the insidious war that’s raging. But on each side of 12th and Delaware, soldiers stand locked in a passionate battle. On one side of the street sits an abortion clinic. On the other, a pro-life outfit often mistaken for the clinic it seeks to shut down. Using skillful cinema-vérité observation that allows us to draw our own conclusions, Rachel Grady and Heidi Ewing, the directors of Jesus Camp, expose the molten core of America’s most intractable conflict. As the pro-life volunteers paint a terrifying portrait of abortion to their clients, across the street, the staff members at the clinic fear for their doctors’ lives and fiercely protect the right of their clients to choose. Shot in the year when abortion provider Dr. George Tiller was murdered in his church, the film makes these FromFrom human rights to popular fears palpable. Meanwhile, women in need cuculture,lt these 16 films become pawns in a vicious ideological war coconfrontnf the subjects that with no end in sight.—CAROLINE LIBRESCO fi dedefine our time. Stylistic ExP: Sheila Nevins AsP: Christina Gonzalez, didiversityv and rigorous Craig Atkinson Ci: Katherine Patterson fifilmmakingl distinguish these Ed: Enat Sidi Mu: David Darling SuP: Sara Bernstein newnew American documentaries. Sunday, January 24, noon - 12DEL24TD Temple Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, noon - 12DEL27YD Yarrow Hotel Theatre, Park City Wednesday, January 27, 9:00 p.m. - 12DEL27BN Broadway Centre Cinemas VI, SLC Thursday, January 28, 9:00 p.m. -

Curriculum Guide Cfi Education Table of Contents Grade Levels 9-12

CURRICULUM GUIDE CFI EDUCATION TABLE OF CONTENTS GRADE LEVELS 9-12 Using this Guide 2 SUBJECTS About the Film 3 • Language Arts Letter from the Filmmakers 3 • Social Studies For the Educator 4 • History Before the Film 4 • Science After the Film 4 • Global Studies Discussion Questions 5 Activities 6 THEMES • Single-use plastics Standards 11 • Environmental justice Resources 12 • Ocean Conservation • Clean Water Handout: • International relationships Documentary Filmmaking • Inequality • Fossil fuel economy • Technology and innovation • Media literacy • Service learning USING THIS GUIDE THE STORY OF PLASTIC challenges students to think critically about how they can contribute to meaningful change when it comes to the way our society regards plastics. Young people have a critical stake in the environmental decisions made today. This standards-aligned study guide helps teachers empower students with tools to become active participants in the public debate over plastic. Teachers can choose from a variety of discussion questions designed to get students talking about themes like media literacy, collective responsibility, and environ- mental justice. Additionally, this guide includes a range of interdisciplinary activities that allow students to apply these concepts to service learning projects that support a global movement to break free from plastics. Curriculum Guide developed by Renée Gasch for CFI Education | © CFI Education 2 THE STORY OF PLASTIC STUDY GUIDE | CFI EDUCATION ABOUT THE FILM Depicting a world rapidly becoming overrun with toxic materials, THE STORY OF PLASTIC brings into focus an alarming, human-made crisis. Striking footage illustrates the ongoing ca- tastrophe: fields full of garbage, veritable mountains of trash; rivers and seas clogged with waste; and skies choked with the poisonous runoff from plastic production and recycling pro- cesses with no end in sight. -

HEAT, FIRE, WATER How Climate Change Has Created a Public Health Emergency Second Edition

By Alan H. Lockwood, MD, FAAN, FANA HEAT, FIRE, WATER How Climate Change Has Created a Public Health Emergency Second Edition Alan H. Lockwood, MD, FAAN, FANA First published in 2019. PSR has not copyrighted this report. Some of the figures reproduced herein are copyrighted. Permission to use them was granted by the copyright holder for use in this report as acknowledged. Subsequent users who wish to use copyrighted materials must obtain permission from the copyright holder. Citation: Lockwood, AH, Heat, Fire, Water: How Climate Change Has Created a Public Health Emergency, Second Edition, 2019, Physicians for Social Responsibility, Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Acknowledgments: The author is grateful for editorial assistance and guidance provided by Barbara Gottlieb, Laurence W. Lannom, Anne Lockwood, Michael McCally, and David W. Orr. Cover Credits: Thermometer, reproduced with permission of MGN Online; Wildfire, reproduced with permission of the photographer Andy Brownbil/AAP; Field Research Facility at Duck, NC, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers HEAT, FIRE, WATER How Climate Change Has Created a Public Health Emergency PHYSICIANS FOR SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY U.S. affiliate of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Recipient of the 1985 Nobel Peace Prize 1111 14th St NW Suite 700, Washington, DC, 20005 email: [email protected] About the author: Alan H. Lockwood, MD, FAAN, FANA is an emeritus professor of neurology at the University at Buffalo, and a Past President, Senior Scientist, and member of the Board of Directors of Physicians for Social Responsibility. He is the principal author of the PSR white paper, Coal’s Assault on Human Health and sole author of two books, The Silent Epidemic: Coal and the Hidden Threat to Health (MIT Press, 2012) and Heat Advisory: Protecting Health on a Warming Planet (MIT Press, 2016). -

US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army

Intelligence and National Security Vol. 25, No. 1, 76–85, February 2010 US Blunders in Iraq: De-Baathification and Disbanding the Army JAMES P. PFIFFNER ABSTRACT In May 2003 Paul Bremer issued CPA Orders to exclude from the new Iraq government members of the Baath Party (CPA Order 1) and to disband the Iraqi Army (CPA Order 2). These two orders severely undermined the capacity of the occupying forces to maintain security and continue the ordinary functioning of the Iraq government. The decisions reversed previous National Security Council judgments and were made over the objections of high ranking military and intelligence officers. The article concludes that the most likely decision maker was the Vice President. Early in the occupation of Iraq two key decisions were made that gravely jeopardized US chances for success in Iraq: (1) the decision to bar from government work Iraqis who ranked in the top four levels of Sadam’s Baath Party or who held positions in the top three levels of each ministry; (2) the decision to disband the Iraqi Army and replace it with a new army built from scratch. These two fateful decisions were made against the advice of military and CIA professionals and without consulting important members of the President’s staff and cabinet. This article will first examine the de- Baathification order and then take up the even more far reaching decision to disband the Iraqi Army. Both of these decisions fueled the insurgency by: (1) alienating hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who could not support themselves or their families; (2) by undermining the normal infrastructure necessary for social and economic activity; (3) by ensuring that there was not sufficient security to carry on normal life; and (4) by creating insurgents who were angry at the US, many of whom had weapons and were trained to use them. -

Brews and Stews by Nicole Feliciano Inter Has Still Got a Firm Grip on New York City

2.24.11 p01-12_Layout 1 2/23/11 8:22 PM Page 1 OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF THE PARK SLOPE FOOD COOP Established 1973 Volume FF, Number 4 February 24, 2011 Brews and Stews By Nicole Feliciano inter has still got a firm grip on New York City. For W many of us, it’s a perfect time to tuck into a hearty winter stew. There’s ample inspiration at the Coop thanks to a plentiful selection of root vegetables and dark leafy greens. But there’s more than just vegetables to generate excitement in the kitchen. To spice up your cooking, consid- er a secret ingredient—beer! The Magic Ingredient vegetables, carrots and The Coop has a wide onions, in this chili. assortment of craft beers that can liven up winter meals. Chefs, Take Note Thanks to the Coop’s intrigu- In a dish like this chili PHOTO COURTESY OF STONYFIELD FARM ing selection, your cooking (recipe to follow), don’t Gary Hirshberg, “CE-YO” of Stonyfield Farm. can get livelier without hav- dump in any old brew: the ing to rely on spices. Sim- A Crisis for Organics ply add beer to a recipe in lieu of broth, The Movement Against water or wine and you’ll change the Engineered Alfalfa character of your favorite By Hayley Gorenberg dish. rganics advocates have raised a chorus of objections following the Beer can enhance fla- U.S. Department of Agriculture’s decision on January 27 to allow vors, add O PHOTO BY KEVIN RYAN nuance to deregulation of genetically engineered alfalfa, the hay many grass-fed cows Ingredients for a hearty winter stew.