The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Controversy Over Climate Change in the Public Sphere

THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN (Under the Direction of Edward Panetta) ABSTRACT The scientific consensus on climate change is not recognized by the public. This is due to many related factors, including the Bush administration’s science policy, the reporting of the controversy by the media, the public’s understanding of science as dissent, and the differing standards of argumentation in science and the public sphere. Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was produced in part as a response to the acceptance of climate dissent by the Bush administration and achieved a rupture of the public sphere by bringing the technical issue forward for public deliberation. The rupture has been sustained by dissenters through the use of argument strategies designed to foster controversy at the expense of deliberation. This makes it incumbent upon rhetorical scholars to theorize the closure of controversy and policymakers to recognize that science will not always have the answers. INDEX WORDS: Al Gore, Argument fields, Argumentation, An Inconvenient Truth, Climate change, Climategate, Controversy, Public sphere, Technical sphere THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN B.A., The University of Wyoming, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 William Mosley-Jensen All Rights Reserved THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN Major Professor: Edward Panetta Committee: Thomas Lessl Roger Stahl Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people that made this project possible through their unwavering support and love. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Our Changing Identity

Being American: Our Changing Identity By Nathan A. Bronstein An Honors Capstone for General University Honors (Spring 2012) Capstone Advisor: Gary Weaver School of International Service 1 Table of Contents 3, Introduction 9, Chapter 1: Culture is an Orange 15, Chapter 2: What… Erm… Who... is American 39, Chapter 3: When in Doubt, Dawn Your Cape 56, Chapter 4: This Land is My Land and Your Land 67, Chapter 5: Technology and us… are In a Relationship 77, Chapter 6: Our Moment 87, Chapter 7: Ah, That’s my Fancy Private School Learnin’ 95, Chapter 8: The Civically Engaged Generation 111, Chapter 9: You’re Hearing Me, Not Listening! 117, Chapter 10: Have Faith 124, Chapter 11: Up, Up, and Abroad! 130, Chapter 12: Renewable Family 137, Chapter 13: Looking Ahead, Now and Then 147, References 2 Introduction: “We go forth all to seek America. And in seeking we create her.” –Waldo Frank I was wearing my Captain America sweatshirt in near 100° weather and I felt good. It was red, white and blue day at the summer camp I have been working at almost every summer since I was 16. The same camp I had attended for five years from 8 to 12. My “leadership” professor, yes, I have a leadership professor, told me that this camp is like cookies and milk; something comforting from my childhood, but something I should move on from. Well… at 22 years of age I love cookies in milk; but I digress. The sweatshirt had been given to me as a Christmas gift from my Student Government staff back at American University in Washington DC. -

Professor Daniel A. Nathan "These Days, Sports May Be What Americans AM 234, American Sports/American Culture Talk About Best

Professor Daniel A. Nathan "These days, sports may be what Americans AM 234, American Sports/American Culture talk about best. With the most knowledge. The TLC 301, WF 10:10-11:30 AM most passion. The most humor. The most Office: TLC 300 (580-5023) distance. The most capacity for a cheerful Office Hours: WF, 2:00-3:30 & by appt. change ofmind. When we meet someone for E-mail: [email protected] the first time, it's no accident that sport becomes the subject so often and so quickly. Yes it's an easy, superficial topic-if we want it to be. But talking about sports has also become one of our best ways ofprobing people, sounding their depth, listening for resonances, judging their values." -Thomas Boswell, sports columnist "Sport is a mirror. Sport is life. Through sport we might know ourselves." -David Guterson, writer Course Description & Objectives This course examines the history of American sports and some aspects of the contemporary athletic landscape as a way to consider cultural values. Sports fans beware: this is not a course in sports trivia, nor is it intended to glamorize the games we watch and play. Rather, we will attempt to situate American sports historically and culturally, paying close attention to issues of commercialization, race/ethnicity, gender, and class, among other subjects, such as globalization and fandom. Employing an interdisciplinary approach that makes use ofprimary documents, history, journalism, economics, anthropology, sociology, and film, we will examine recurrent cultural values expressed via American sports and iconic athletes. This course is not intended as a comprehensive survey of American sports. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Literature, Peda

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE STUDENTS OF HUMAN RIGHTS: LITERATURE, PEDAGOGY, AND THE LONG SIXTIES IN THE AMERICAS A Dissertation in Comparative Literature by Molly Appel © 2018 Molly Appel Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 ii The dissertation of Molly Appel was reviewed and approved* by the following: Rosemary Jolly Weiss Chair of the Humanities in Literature and Human Rights Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Thomas O. Beebee Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Comparative Literature and German Charlotte Eubanks Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Japanese, and Asian Studies Director of Graduate Studies John Ochoa Associate Professor of Spanish and Comparative Literature Sarah J. Townsend Assistant Professor of Spanish and Portuguese Robert R. Edwards Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of English and Comparative Literature Head of the Department of Comparative Literature *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT In The Students of Human Rights, I propose that the role of the cultural figure of the American student activist of the Long Sixties in human rights literature enables us to identify a pedagogy of deficit and indebtedness at work within human rights discourse. My central argument is that a close and comparative reading of the role of this cultural figure in the American context, anchored in three representative cases from Argentina—a dictatorship, Mexico—a nominal democracy, and Puerto Rico—a colonially-occupied and minoritized community within the United States, reveals that the liberal idealization of the subject of human rights relies upon the implicit pedagogical regulation of an educable subject of human rights. -

The Reel World: Contemporary Issues on Screen

The Reel World: Contemporary Issues on Screen Films • “Before the Rain” (Macedonia 1994) or “L’America” (Italy/Albania 1994) • “Earth” (India 1998) • “Xiu-Xiu the Sent Down Girl” (China 1999) • (OPTIONAL): “Indochine” (France/Vietnam 1992) • “Zinat” (Iran 1994) • “Paradise Now” (Palestine 2005) • “Hotel Rwanda” (Rwanda 2004) • (OPTIONAL): “Lumumba” (Zaire 2002) • “A Dry White Season” (South Africa 1989) • “Missing” (US/Chile 1982) • “Official Story” (Argentina 1985) • “Men With Guns” (Central America 1997) Books • We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will be Killed With Our Families: Stories from Rwanda by Philip Gourevitch • (OPTIONAL/RECOMMENDED): A Dry White Season by André Brink Course Goals There are several specific goals to achieve for the course: Students will learn to view films historically as one of a number of sources offering an interpretation of the past Students will acquire a knowledge of the key terms, facts, and events in contemporary world history and thereby gain an informed historical perspective Students will take from the class the skills to critically appraise varying historical arguments based on film and to clearly express their own interpretations Students will develop the ability to synthesize and integrate information and ideas as well as to distinguish between fact and opinion Students will be encouraged to develop an openness to new ideas and, most importantly, the capacity to think critically Course Activities and Procedures This course is taught in conjunction with “The Contemporary World,” although that course is not a prerequisite. We will use material from that course as background and context for the films we see. Students who have already taken “The Contemporary World” can review the material to refresh their memories before watching the relevant titles if they feel the need to do so. -

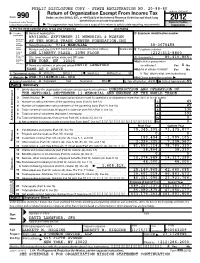

2012 Form 990 Or 990‐EZ

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY - STATE REGISTRATION NO. 20-88-80 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2012 Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service | The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. Inspection A For the 2012 calendar year, or tax year beginning and ending B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable: NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL & MUSEUM Address change AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER FOUNDATION,INC Name change Doing Business As 9/11 MEMORIAL 38-3678458 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Termin- ated ONE LIBERTY PLAZA, 20TH FLOOR (212)312-8800 Amended return City, town, or post office, state, and ZIP code G Gross receipts $ 85,416,865. Applica- tion NEW YORK, NY 10006 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer:DAVID LANGFORD for affiliates? Yes X No SAME AS C ABOVE H(b) Are all affiliates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )§ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: | WWW.911MEMORIAL.ORG H(c) Group exemption number | K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other | L Year of formation: 2003 M State of legal domicile: NY Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATION OF THE NATIONAL SEPTEMBER 11 MEMORIAL AND MUSEUM AT THE WORLD TRADE 2 Check this box | if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Southeastern Ohio's Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil

They Fought the War Together: Southeastern Ohio’s Soldiers and Their Families During the Civil War A Dissertation Submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gregory R. Jones December, 2013 Dissertation written by Gregory R. Jones B.A., Geneva College, 2005 M.A., Western Carolina University, 2007 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2013 Approved by Dr. Leonne M. Hudson, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Bradley Keefer, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Members Dr. John Jameson Dr. David Purcell Dr. Willie Harrell Accepted by Dr. Kenneth Bindas, Chair, Department of History Dr. Raymond A. Craig, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements.............................................................................................................iv Introduction..........................................................................................................................7 Chapter 1: War Fever is On: The Fight to Define Patriotism............................................26 Chapter 2: “Wars and Rumors of War:” Southeastern Ohio’s Correspondence on Combat...............................................................................................................................60 Chapter 3: The “Thunderbolt” Strikes Southeastern Ohio: Hardships and Morgan’s Raid....................................................................................................................................95 Chapter 4: “Traitors at Home”: