Introduction Matthew H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brookings Institution

1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION Brookings Briefing PUBLIC PHILOSOPHY: WHY MORALITY MATTERS IN POLITICS Tuesday, January 24, 2006 MICHAEL SANDEL WILLIAM GALSTON CHARLES KRAUTHAMMER E.J. DIONNE, JR., Moderator [TRANSCRIPT PRODUCED FROM A TAPE RECORDING] MILLER REPORTING CO., INC. 735 8th STREET, S.E. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20003-2802 (202) 546-6666 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. DIONNE: [In progress] —become important to their time not by seeking in a contrived and silly way something called relevance, they become important to their time by thinking clearly systematically and insightfully about public issues and public problems. And by that measure, Mike Sandel is truly one of our moment's most important political and public philosophers. So I loved it when Mike finally put out this collection called "Public Philosophy," of which we in general and, I personally believe, liberals in particular are very much in search of. I just want to read one brief passage from the beginning of Mike's book, which gives you a sense of how relevant his discussion is to our moment. He notes that the Democrats have been struggling for awhile over what some call the "moral values thing." "When Democrats in recent times have reached for moral and religious resonance," he writes, "their efforts have taken two forms, neither wholly convincing. Some, following the example of George W. Bush, have sprinkled their speeches with religious rhetoric and biblical references. So intense was the competition for divine favor in the 2000 and 2004 campaigns that a Web site, beliefnet.com, established a God-o- meter to track the candidates' references to God. -

The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations In

Capturing the Void: The Importance of Collective Visual Memories in the Representations in Documentary Films on September 11, 2001 Jodye D. Whitesell Undergraduate Honors Thesis Department of Film Studies Advisor: Dr. Jennifer Peterson October 24, 2012 Committee Members: Dr. Jennifer Peterson, Film Studies Dr. Melinda Barlow, Film Studies Dr. Carole McGranahan, Anthropology Table of Contents: Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Part I: The Progression of Documentary Film Production………………………………… 9 Part II: September 11, 2001….…………………………………………………………….. 15 Part III: The Immediate Role of the Media………………………………………………... 18 Part IV: Collective Memories and the Media,,,……………………………………………. 25 Part V: The Turn Towards Documentary…………………………………….……………. 34 (1) Providing a Historical Record…………………………………….……………. 36 (2) Challenging the Official Story…………………………………………………. 53 (3) Memorializing the Fallen………………………………………………………. 61 (4) Recovering from the Trauma…………………………………………………... 68 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………. 79 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………... 83 2 Abstract: Documentary films have long occupied a privileged role among audiences as the purveyors of truth, offering viewers accurate reproductions of reality. While this classification is debatable, the role of documentaries as vehicles for collective memory is vital to the societal reconstructions of historical events, a connection that must be understood in order to properly assign meaning to the them. This thesis examines this relationship, focusing specifically on the documentaries produced related to trauma (in this case the September 11 attacks on the United States) as a means to enhance understanding of the role these films play in the lives and memories of their collective audiences. Of the massive collection of 9/11 documentaries produced since 2001, twenty-three were chosen for analysis based on national significance, role as a representative of a category (e.g. -

Cinema of the Dark Side Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship

Cinema of the Dark Side Atrocity and the Ethics of Film Spectatorship Shohini Chaudhuri CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 1 26/09/2014 16:33 © Shohini Chaudhuri, 2014 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ www.euppublishing.com Typeset in Monotype Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 4263 2 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 0042 8 (paperback) ISBN 978 0 7486 9461 7 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 0043 5 (epub) The right of Shohini Chaudhuri to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 2 26/09/2014 16:33 Contents Acknowledgements iv List of Figures viii Introduction 1 1 Documenting the Dark Side: Fictional and Documentary Treatments of Torture and the ‘War On Terror’ 22 2 History Lessons: What Audiences (Could) Learn about Genocide from Historical Dramas 50 3 The Art of Disappearance: Remembering Political Violence in Argentina and Chile 84 4 Uninvited Visitors: Immigration, Detention and Deportation in Science Fiction 115 5 Architectures of Enmity: the Israeli–Palestinian Conflict through a Cinematic Lens 146 Conclusion 178 Bibliography 184 Index 197 CHAUDHURI 9780748642632 PRINT.indd 3 26/09/2014 16:33 Introduction n the science fiction film Children of Men (2006), set in a future dystopian IBritain, a propaganda film plays on a TV screen on a train. -

A Pilot Method for Movie Selection and Initial Results

Movies for use in Public Health Training: A Pilot Method for Movie Selection and Initial Results Nick Wilson,* Rachael Cowie, Michael G Baker, Philippa Howden-Chapman Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand October 2009 *Correspondence to: Dr Nick Wilson Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington PO Box 7343 Wellington South, New Zealand. Phone (64)-4-385 5541 ext. 6469 Fax (64)-4-389 5319 Email: [email protected] Abstract Background: A method for systematically identifying, selecting, and ranking high quality movies for public health training does not exist. We therefore aimed to pilot a method and use it to generate an initial selection of suitable movies in a range of public health categories. Methods: To identify possible movies, systematic searches were undertaken of two large movie databases. If meeting minimal criteria for entertainment value (using public and critic ratings), the movies were then systematically evaluated for training suitability. Results: Using the search strategy we developed, it appeared feasible to systematically identify movies of potential educational value for public health training. Out of a total of 29 movies selected for viewing and more detailed assessment, the top ranked 15 were selected as having reasonable potential for training. There was a high correlation between scores of the movie assessors (Spearman’s rho = 0.80, p<0.00001). Also 75% of the top 15 movies were found to be referred to in Medline-indexed publications. Conclusion: This pilot study was able to develop a method for systematically identifying and selecting movies that could potentially be used for public health training. -

A Call for Change: the Evolution of the Modern Documentary From

England | 1 A Call for Change: The Evolution of the Modern Documentary from Informative Media to Persuasive Platform Valerie England San Jose State University Communication Studies 145i: Rhetorical Criticism Gina Firenzi December 14, 2011 Abstract England | 2 In the past several years, new documentaries have begun to evolve from informative media to persuasive platform as a result of changing cultural contexts and ideologies. These four films – Sicko, Food Inc., Waiting for Superman, and Inside Job effectively utilize common narratives and themes to present audiences with calls for reform in critical areas such as food safety, quality education, access to healthcare, and financial regulation. This shift reflects a transformation of the valuation of knowledge and how it serves various conflicting group interests. In an increasingly materialistic and visual culture, where media holds hegemonic sway over mass audiences through its reinforcement of dominant meanings and perspectives, the “success” of a film is often understood by the public in terms of sales. Documentaries have suddenly become rather lucrative in the last several years and are enjoying large gains at the box office. Michael Moore’s Sicko , for example, wowed at $24.5 million in the United States alone. Others would argue that their success is rather limited, pointing out the one-sidedness of directors’ perspectives and apparent unwillingness to present all aspects to an issue. Success from this perspective is defined not by commercial gains but by objectivity and faithful representation of facts outside of personal belief or political agenda. The new documentaries shown in movie theatres are anything but; controversy surrounds many current releases, with sparks flying between critics who laud – or denigrate – the relative fairness of truths and conclusions presented to audiences. -

Hulu No Longer for Sale, Owners Say 14 October 2011, by RYAN NAKASHIMA , AP Business Writer

Hulu no longer for sale, owners say 14 October 2011, By RYAN NAKASHIMA , AP Business Writer After months of being courted by technology giants launching the premium tier last November. CEO and TV signal providers, online video service Hulu Jason Kilar has said Hulu is on track to make is no longer for sale, its media company owners around $500 million in revenue this year, up from said Thursday. $263 million in 2010, and that the company is profitable. The Walt Disney Co., News Corp., Comcast Corp. and Providence Equity Partners had been In comparison, Netflix had 24.6 million paying shopping the site since June after receiving an subscribers at the end of June, but it warned last unsolicited takeover offer. month that it expected a net 600,000 to leave by the end of September after a series of unpopular They tested the waters for other interest, and decisions. They included hiking prices as much as dozens of companies, from Internet giants Google 60 percent on millions of customers and splitting its Inc. and Yahoo Inc. to satellite TV providers Dish streaming and DVD-by-mail services into two Network Corp. and DirecTV, began circling. separately-billed operations, a move it has since reversed. But the owners said in a joint statement Thursday that Hulu "holds a unique and compelling strategic Hulu's value may have fallen after consumers were value to each of its owners" and that they would seen railing against Netflix's price increase and refocus on "mapping out its path to even greater Netflix balked at paying an estimated $300 million a success." year for Disney and Sony movies through pay TV channel Starz, said Needham & Co. -

The Controversy Over Climate Change in the Public Sphere

THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN (Under the Direction of Edward Panetta) ABSTRACT The scientific consensus on climate change is not recognized by the public. This is due to many related factors, including the Bush administration’s science policy, the reporting of the controversy by the media, the public’s understanding of science as dissent, and the differing standards of argumentation in science and the public sphere. Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth was produced in part as a response to the acceptance of climate dissent by the Bush administration and achieved a rupture of the public sphere by bringing the technical issue forward for public deliberation. The rupture has been sustained by dissenters through the use of argument strategies designed to foster controversy at the expense of deliberation. This makes it incumbent upon rhetorical scholars to theorize the closure of controversy and policymakers to recognize that science will not always have the answers. INDEX WORDS: Al Gore, Argument fields, Argumentation, An Inconvenient Truth, Climate change, Climategate, Controversy, Public sphere, Technical sphere THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN B.A., The University of Wyoming, 2008 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2010 © 2010 William Mosley-Jensen All Rights Reserved THE CONTROVERSY OVER CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE PUBLIC SPHERE by WILLIAM MOSLEY-JENSEN Major Professor: Edward Panetta Committee: Thomas Lessl Roger Stahl Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2010 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people that made this project possible through their unwavering support and love. -

A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2007 Art and Persuasion: A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film Lauren Elizabeth Freeman Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Freeman, Lauren Elizabeth, "Art and Persuasion: A Communication Study of Contemporary Documentary Film" (2007). Honors Theses. 2004. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2004 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ART AND PERSUASION: A COMMUNICATION STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY DOCUMENTARY FILM By Lauren Elizabeth Freeman A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford May 2007 Approved by , , L Ad^or: Professor Joe Atkins Readei1p^fessoLPmch£ll££maiiuel,PhD Reader: Professor Charles Gates, PhD ©2007 Lauren Elizabeth Freeman ALL RIGHTS RESRERVED ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author of this paper incurs many debts of gratitude throughout the long and tedious process of completing this honors senior thesis. A special expression of gratitude goes to my thesis adviser, Professor Joseph Atkins, for his supportive direction throughout the preparation of this research project. Sincere appreciation is extended to niy thesis readers. Dr. Michelle Emanuel and Dr. Charles Gates, and to those filmmakers who shared their time and thoughts with me on documentary filmmaking. I extend my heartfelt gratitude to my family and fnends for their continued support and encouragement. -

485 Svilicic.Vp

Coll. Antropol. 37 (2013) 4: 1327–1338 Original scientific paper The Popularization of the Ethnological Documentary Film at the Beginning of the 21st Century Nik{a Svili~i}1 and Zlatko Vida~kovi}2 1 Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia 2 University of Zagreb, Academy of Dramatic Art, Zagreb, Croatia ABSTRACT This paper seeks to explain the reasons for the rising popularity of the ethnological documentary genre in all its forms, emphasizing its correlation with contemporary social events or trends. The paper presents the origins and the de- velopment of the ethnological documentary film in the anthropological domain. Special attention is given to the most in- fluential documentaries of the last decade, dealing with politics: (Fahrenheit 9/1, Bush’s Brain), gun control (Bowling for Columbine), health (Sicko), the economy (Capitalism: A Love Story), ecology An Inconvenient Truth) and food (Super Size Me). The paper further analyzes the popularization of the documentary film in Croatia, the most watched Croatian documentaries in theatres, and the most controversial Croatian documentaries. It determines the structure and methods in the making of a documentary film, presents the basic types of scripts for a documentary film, and points out the differ- ences between scripts for a documentary and a feature film. Finally, the paper questions the possibility of capturing the whole truth and whether some documentaries, such as the Croatian classics: A Little Village Performance and Green Love, are documentaries at all. Key words: documentary film, anthropological topics, script, ethnographic film, methods, production, Croatian doc- umentaries Introduction This paper deals with the phenomenon of the popu- the same time, creating a work of art. -

1997 Sundance Film Festival Awards Jurors

1997 SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL The 1997 Sundance Film Festival continued to attract crowds, international attention and an appreciative group of alumni fi lmmakers. Many of the Premiere fi lmmakers were returning directors (Errol Morris, Tom DiCillo, Victor Nunez, Gregg Araki, Kevin Smith), whose earlier, sometimes unknown, work had received a warm reception at Sundance. The Piper-Heidsieck tribute to independent vision went to actor/director Tim Robbins, and a major retrospective of the works of German New-Wave giant Rainer Werner Fassbinder was staged, with many of his original actors fl own in for forums. It was a fi tting tribute to both Fassbinder and the Festival and the ways that American independent cinema was indeed becoming international. AWARDS GRAND JURY PRIZE JURY PRIZE IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Documentary—GIRLS LIKE US, directed by Jane C. Wagner and LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY (O SERTÃO DAS MEMÓRIAS), directed by José Araújo Tina DiFeliciantonio SPECIAL JURY AWARD IN LATIN AMERICAN CINEMA Dramatic—SUNDAY, directed by Jonathan Nossiter DEEP CRIMSON, directed by Arturo Ripstein AUDIENCE AWARD JURY PRIZE IN SHORT FILMMAKING Documentary—Paul Monette: THE BRINK OF SUMMER’S END, directed by MAN ABOUT TOWN, directed by Kris Isacsson Monte Bramer Dramatic—HURRICANE, directed by Morgan J. Freeman; and LOVE JONES, HONORABLE MENTIONS IN SHORT FILMMAKING directed by Theodore Witcher (shared) BIRDHOUSE, directed by Richard C. Zimmerman; and SYPHON-GUN, directed by KC Amos FILMMAKERS TROPHY Documentary—LICENSED TO KILL, directed by Arthur Dong Dramatic—IN THE COMPANY OF MEN, directed by Neil LaBute DIRECTING AWARD Documentary—ARTHUR DONG, director of Licensed To Kill Dramatic—MORGAN J. -

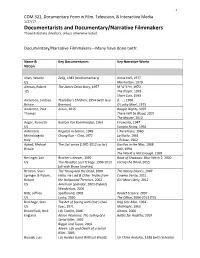

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012

Copyright by Leah Michelle Ross 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Leah Michelle Ross Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Barry Brummett, Co-Supervisor Richard Cherwitz Dana Cloud Andrew Garrison A Rhetoric of Instrumentality: Documentary Film in the Landscape of Public Memory by Leah Michelle Ross, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2012 Dedication For Chaim Silberstrom, who taught me to choose life. Acknowledgements This dissertation was conceived with insurmountable help from Dr. Katherine Arens, who has been my champion in both my academic work as well as in my personal growth and development for the last ten years. This kind of support and mentorship is rare and I can only hope to embody the same generosity when I am in the position to do so. I am forever indebted. Also to William Russell Hart, who taught me about strength in the process of recovery. I would also like to thank my dissertation committee members: Dr Barry Brummett for his patience through the years and maintaining a discipline of cool; Dr Dana Cloud for her inspiring and invaluable and tireless work on social justice issues, as well as her invaluable academic support in the early years of my graduate studies; Dr. Rick Cherwitz whose mentorship program provides practical skills and support to otherwise marginalized students is an invaluable contribution to the life of our university and world as a whole; Andrew Garrison for teaching me the craft I continue to practice and continuing to support me when I reach out with questions of my professional and creative goals; an inspiration in his ability to juggle filmmaking, teaching, and family and continued dedication to community based filmmaking programs.