XUN XU's FIRST POSTS, CA. 248–265 We Know Next to Nothing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 32. Last

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 32. Last time, Yuan Shao had mobilized his forces to attack Cao Cao, who responded by leading an army to meet Yuan Shao’s vanguard at the city of Baima (2,3). However, Cao Cao’s operation ran into a roadblock by the name of Yan Liang, Yuan Shao’s top general who easily slayed two of Cao Cao’s lesser officers. Feeling the need for a little more firepower, Cao Cao sent a messenger to the capital to summon Guan Yu. When Guan Yu received the order, he went to inform his two sisters-in-law, who reminded him to try to find some news about Liu Bei on this trip. Guan Yu then took his leave, grabbed his green dragon saber, hopped on his Red Hare horse, and led a few riders to Baima to see Cao Cao. “Yan Liang killed two of my officers and his valor is hard to match,” Cao Cao said. “That’s why I have invited you here to discuss how to deal with him.” “Allow me to observe him first,” Guan Yu said. Cao Cao had just laid out some wine to welcome Guan Yu when word came that Yan Liang was challenging for combat. So Guan Yu and Cao Cao went to the top of the hill to observe their enemy. Cao Cao and Guan Yu both sat down, while all the other officers stood. In front of them, at the bottom of the hill, Yan Liang’s army lined up in an impressive and disciplined formation, with fresh and brilliant banners and countless spears. -

Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880S-1940S

Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hashimoto, Satoru. 2014. Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:13064962 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s A dissertation presented by Satoru Hashimoto to The Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of East Asian Languages and Civilizations Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2014 ! ! © 2014 Satoru Hashimoto All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor David Der-Wei Wang Satoru Hashimoto Afterlives of the Culture: Engaging with the Trans-East Asian Cultural Tradition in Modern Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese Literatures, 1880s-1940s Abstract This dissertation examines how modern literature in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan in the late-nineteenth to the early-twentieth centuries was practiced within contexts of these countries’ deeply interrelated literary traditions. -

Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5

JCC: Romance of the Three Kingdoms 三國演義 Cao Cao Dossier 曹操 Crisis Director: Matthew Owens, Charles Miller Email: [email protected], [email protected] Chair: Harjot Singh Email: [email protected] Table of Contents: 1. Front Page (Page 1) 2. Table of Contents (Page 2) 3. Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier (Pages 3-4) 4. Cao Pi (Pages 5-6) 5. Cao Zhang (Pages 7-8) 6. Cao Zhi (Pages 9-10) 7. Lady Bian (Page 11) 8. Emperor Xian of Han (Pages 12-13) 9. Empress Fu Shou (Pages 14-15) 10. Cao Ren (Pages 16-17) 11. Cao Hong (Pages 18-19) 12. Xun Yu (Pages 20-21) 13. Sima Yi (Pages 22-23) 14. Zhang Liao (Pages 24-25) 15. Xiahou Yuan (Pages 26-27) 16. Xiahou Dun (Pages 28-29) 17. Yue Jin (Pages 30-31) 18. Dong Zhao (Pages 32-33) 19. Xu Huang (Pages 34-35) 20. Cheng Yu (Pages 36-37) 21. Cai Yan (Page 38) 22. Han Ji (Pages 39-40) 23. Su Ze (Pages 41-42) 24. Works Cited (Pages 43-) Introduction to the Cao Cao Dossier: Most characters within the Court of Cao Cao are either generals, strategists, administrators, or family members. ● Generals lead troops on the battlefield by both developing successful battlefield tactics and using their martial prowess with skills including swordsmanship and archery to duel opposing generals and officers in single combat. They also manage their armies- comprising of troops infantrymen who fight on foot, cavalrymen who fight on horseback, charioteers who fight using horse-drawn chariots, artillerymen who use long-ranged artillery, and sailors and marines who fight using wooden ships- through actions such as recruitment, collection of food and supplies, and training exercises to ensure that their soldiers are well-trained, well-fed, well-armed, and well-supplied. -

P020110307527551165137.Pdf

CONTENT 1.MESSAGE FROM DIRECTOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 03 2.ORGANIZATION STRUCTURE …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 05 3.HIGHLIGHTS OF ACHIEVEMENTS …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 Coexistence of Conserve and Research----“The Germplasm Bank of Wild Species ” services biodiversity protection and socio-economic development ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 06 The Structure, Activity and New Drug Pre-Clinical Research of Monoterpene Indole Alkaloids ………………………………………… 09 Anti-Cancer Constituents in the Herb Medicine-Shengma (Cimicifuga L) ……………………………………………………………………………… 10 Floristic Study on the Seed Plants of Yaoshan Mountain in Northeast Yunnan …………………………………………………………………… 11 Higher Fungi Resources and Chemical Composition in Alpine and Sub-alpine Regions in Southwest China ……………………… 12 Research Progress on Natural Tobacco Mosaic Virus (TMV) Inhibitors…………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Predicting Global Change through Reconstruction Research of Paleoclimate………………………………………………………………………… 14 Chemical Composition of a traditional Chinese medicine-Swertia mileensis……………………………………………………………………………… 15 Mountain Ecosystem Research has Made New Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 Plant Cyclic Peptide has Made Important Progress ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 17 Progresses in Computational Chemistry Research ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 18 New Progress in the Total Synthesis of Natural Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Download (3MB)

Lipsey, Eleanor Laura (2018) Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/32199 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Music motifs in Six Dynasties texts Eleanor Laura Lipsey Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2018 Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures China & Inner Asia Section SOAS, University of London 1 Abstract This is a study of the music culture of the Six Dynasties era (220–589 CE), as represented in certain texts of the period, to uncover clues to the music culture that can be found in textual references to music. This study diverges from most scholarship on Six Dynasties music culture in four major ways. The first concerns the type of text examined: since the standard histories have been extensively researched, I work with other types of literature. The second is the casual and indirect nature of the references to music that I analyze: particularly when the focus of research is on ideas, most scholarship is directed at formal essays that explicitly address questions about the nature of music. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

University of California Riverside

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Xi Tian August 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson Dr. Paul Pickowicz Dr. Yenna Wu Copyright by Xi Tian 2014 The Dissertation of Xi Tian is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Uncertain Satire in Modern Chinese Fiction and Drama: 1930-1949 by Xi Tian Doctor of Philosophy, Graduate Program in Comparative Literature University of California, Riverside, August 2014 Dr. Perry Link, Chairperson My dissertation rethinks satire and redefines our understanding of it through the examination of works from the 1930s and 1940s. I argue that the fluidity of satiric writing in the 1930s and 1940s undermines the certainties of the “satiric triangle” and gives rise to what I call, variously, self-satire, self-counteractive satire, empathetic satire and ambiguous satire. It has been standard in the study of satire to assume fixed and fairly stable relations among satirist, reader, and satirized object. This “satiric triangle” highlights the opposition of satirist and satirized object and has generally assumed an alignment by the reader with the satirist and the satirist’s judgments of the satirized object. Literary critics and theorists have usually shared these assumptions about the basis of satire. I argue, however, that beginning with late-Qing exposé fiction, satire in modern Chinese literature has shown an unprecedented uncertainty and fluidity in the relations among satirist, reader and satirized object. -

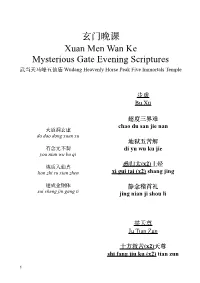

救苦(X2)天尊 Shi Fang Jiu Ku (X2) Tian Zun

玄门晚课 Xuan Men Wan Ke Mysterious Gate Evening Scriptures 武当天马峰五仙庙 Wudang Heavenly Horse Peak Five Immortals Temple 步虚 Bu Xü 超度三界难 chao du san jie nan ⼤道洞玄虚 da dao dong xuan xu 地狱五苦解 有念无不契 di yu wu ku jie you nian wu bu qi (x2) 炼质入仙真 悉归太 上经 lian zhi ru xian zhen xi gui tai (x2) shang jing 遂成⾦钢体 静念稽⾸礼 sui cheng jin gang ti jing nian ji shou li 举天尊 Ju Tian Zun ⼗⽅救苦(x2)天尊 shi fang jiu ku (x2) tian zun !1 吊挂 便是升天(x2)得道⼈ Diao Gua bian shi sheng tian (x2) de dao ren 种种无名(x2)是苦(x2)根 zhong zhong wu ming (x2) shi ku (x2)gen ⾹供养 苦根除尽(x2)善根存 Xiang Gong Yang ku gen chu jin (x2) shan gen (only on 1st and 15th) cun ⾹供养太⼄(x2)救苦天尊 但凭慧剑(x2)威神(x2)⼒ xiang gong yang tai yi (x2) jiu dan ping hui jian (x2)wei ku tian zun shen (x2) li 跳出轮回(x2)无苦门 提纲 tiao chu lun hui(x2) wu ku Ti Gang men (only on 1st and 15th) 道以无⼼(x2)度有(x2)情 ⼀柱真⾹烈⽕焚 dao yi wu xin (x2) du you (x2) yi zhu zhen xiang lie huo fen qing ⾦童⽟女上遥闻 ⼀切⽅便(x2)是修真 jin tong yu nü shang yao wen yi qie fang bian (x2) shi xiu zhen 此⾹径达青华府 ci xiang jing da qing hua fu 若皈圣智(x2)圆通(x2)地 ruo gui sheng zhi (x2) yuan 奏启寻声救苦尊 tong(x2) di zou qi xun sheng jiu ku zun !2 反八天 提纲 Fan Ba Tian Ti Gang (only on 1st and 15th) 道场众等 dao chang zhong deng 救苦天尊妙难量 jiu ku tian zun miao nan liang ⼈各恭敬 ren ge gong jing 开化⼈天度众⽣ kai hua ren tian du zhong 恭对道前 sheng gong dui dao qian 存亡两途皆利济 诵经如法 cun wang liang tu jie li ji song jing ru fa 众等讽诵太上经 zhong deng feng song tai shang jing !3 玄蕴咒 真⼈无上德 Xuan Yun Zhou zhen ren wu shang de 寂寂至无宗 世世为仙家 ji ji zhi wu zong shi shi wei xian jia 虚峙劫仞阿 xu zhi jie ren e 豁落洞玄⽂ huo luo dong xuan wen 谁测此幽遐 -

Remaking History: the Shu and Wu Perspectives in the Three Kingdoms Period

Remaking History: The Shu and Wu Perspectives in the Three Kingdoms Period The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Xiaofei Tian. 2016. “Remaking History: The Shu and Wu Perspectives in the Three Kingdoms Period.” Journal of the American Oriental Society 136 (4): 705. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.4.0705. Published Version doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.4.0705 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34390354 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Remaking History: The Shu and Wu Perspectives in the Three Kingdoms Period XIAOFEI TIAN HARVARD UNIVERSITY Of the three powers—Wei, Shu, and Wu—that divided China for the better part of the third century, Wei has received the most attention in the standard literary historical accounts. In a typical book of Chinese literary history in any language, little, if anything, is said about Wu and Shu. This article argues that the consider- ation of the literary production of Shu and Wu is crucial to a fuller picture of the cultural dynamics of the Three Kingdoms period. The three states competed with one another for the claim to political legitimacy and cultural supremacy, and Wu in particular was in a position to contend with Wei in its cultural undertakings, notably in the areas of history writing and ritual music. -

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This Is Episode 29. When

Welcome to the Romance of the Three Kingdoms Podcast. This is episode 29. When we last left off, Cao Cao and Yuan Shao were in a standoff in Hebei (2,3), while in Xu Province, Liu Bei had captured one of the two lowly officers Cao Cao had sent to attack him, and Zhang Fei had the other officer, Liu (2) Dai (4), so scared that he won’t come out of his camp to fight. After a few days of hurling all the insults he could think of to try to spur Liu Dai to give battle, Zhang Fei had an idea. He sent out word to his men that they were to prepare for a night raid around 9 o’clock that night. During the day, however, Zhang Fei sat in his tent and drank, and after a few drinks, he pretended to be drunk. He then found some excuse to get ticked off at some unfortunate soldier and gave him a good whipping. After the beating, Zhang Fei ordered the soldier to be tied up. “When I set out on my raid tonight,” Zhang Fei said, “I will kill him as a sacrifice to my banner.” But at the same time, he also secretly instructed the guards to be rather derelict of their duty. The condemned man, seeing an opening, slipped out and escaped to Liu Dai’s camp, where he spilled the beans about Zhang Fei’s plans for a night raid. Liu Dai, seeing the very real wounds on this informant, believed him, so he set up an ambush where he left his camp empty and had his soldier lie in wait outside. -

The Lyrics of Zhou Bangyan (1056-1121): in Between Popular and Elite Cultures

THE LYRICS OF ZHOU BANGYAN (1056-1121): IN BETWEEN POPULAR AND ELITE CULTURES by Zhou Huarao A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Zhou Huarao, 2014 The Lyrics of Zhou Bangyan (1056-1121): In between Popular and Elite Cultures Huarao Zhou Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Successfully synthesizing all previous styles of the lyric, or ci, Zhou Bangyan’s (1056-1121) poems oscillate between contrasting qualities in regard to aesthetics (ya and su), generic development (zheng and bian), circulation (musicality and textuality), and literary value (assumed female voice and male voice, lyrical mode and narrative mode, and the explicit and the implicit). These qualities emerged during the evolution of the lyric genre from common songs to a specialized and elegant form of art. This evolution, promoted by the interaction of popular culture and elite tradition, paralleled the canonization of the lyric genre. Therefore, to investigate Zhou Bangyan’s lyrics, I situate them within these contrasting qualities; in doing so, I attempt to demonstrate the uniqueness and significance of Zhou Bangyan’s poems in the development and canonization of the lyric genre. This dissertation contains six chapters. Chapter One outlines the six pairs of contrasting qualities associated with popular culture and literati tradition that existed in the course of the development of the lyric genre. These contrasting qualities serve as the overall framework for discussing Zhou Bangyan’s lyrics in the following chapters. Chapter Two studies Zhou Bangyan’s life, with a focus on how biographical factors shaped his perspective about the lyric genre. -

Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2003 Number 129 Article 6 2-1-2003 Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans Sheau-yueh J. Chao Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chao, Sheau-yueh J. (2003) "Researching Your Asian Roots for Chinese-Americans," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2003 : No. 129 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2003/iss129/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. researching YOUR ASIAN ROOTS CHINESE AMERICANS sheau yueh J chao baruch college city university new york introduction situated busiest mid town manhattan baruch senior colleges within city university new york consists twenty campuses spread five boroughs new york city intensive business curriculum attracts students country especially those asian pacific ethnic background encompasses nearly 45 entire student population baruch librarian baruch college city university new york I1 encountered various types questions serving reference desk generally these questions solved without major difficulties however beginning seven years ago unique question referred me repeatedly each new semester began how I1 find reference book trace my chinese name resource english help me find origin my chinese surname