Issue 172 - November 2011 Printable Version | for Free Subscription | Previous Issues Also Available in French, Portuguese and Spanish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sustainable Biofuel Contributions to Carbon Mitigation and Energy Independence

Forests 2011, 2, 861-874; doi:10.3390/f2040861 OPEN ACCESS forests ISSN 1999-4907 www.mdpi.com/journal/forests Article Sustainable Biofuel Contributions to Carbon Mitigation and Energy Independence Bruce Lippke 1,*, Richard Gustafson 1, Richard Venditti 2, Timothy Volk 3, Elaine Oneil 1, Leonard Johnson 4, Maureen Puettmann 5 and Phillip Steele 6 1 Anderson Hall, Room 107, School of Forest Resources, College of Environment, University of Washington, P.O. Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.G.); [email protected] (E.O.) 2 Department of Forest Biomaterials, College of Natural Resources, North Carolina State University, 2820 Faucette Drive, Raleigh, NC 27695-8005, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Forest and Natural Resources Management, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Leonard Johnson and Associates, 1205 Kamiaken, Moscow, ID 83843, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 WoodLife Environmental Consultants, LLC, 8200 NW Chaparral Drive, Corvallis, OR 97330, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Forest Products, Building 1, Room 1201, Department of Forest Products, Mississippi State University, P.O. Box 9820, Mississippi State, MS 39762-9820, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-543-8684; Fax: +1-206-685-0790. Received: 17 August 2011; in revised form: 25 September 2011 / Accepted: 27 September 2011 / Published: 19 October 2011 Abstract: The growing interest in US biofuels has been motivated by two primary national policy goals, (1) to reduce carbon emissions and (2) to achieve energy independence. -

Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report

Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report Carbon Offset Watch www.carbonoffsetwatch.org.au 2008 1 CARBON OFFSET WATCH 2008 Assessment Report Authors Chris Riedy & Alison Atherton Institute for Sustainable Futures © UTS 2008 Supported by the Albert George and Nancy Caroline Youngman Trust as administered by Equity Trustees Limited Disclaimer While all due care and attention has been taken to establish the accuracy of the material published, UTS/ISF and the authors disclaim liability for any loss that may arise from any person acting in reliance upon the contents of this document. Please cite this report as: Riedy, C. and Atherton, A. 2008, Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report. The Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology, Sydney. Carbon Offset Watch www.carbonoffsetwatch.org.au 2008 2 Carbon Offset Watch Tips for buying carbon offsets > Before you consider buying offsets, try to reduce > Choose offset projects that change or prevent the your carbon footprint as much as possible. For tips underlying activities that create greenhouse gases. on reducing your carbon footprint see Global These are best for combating climate change in the Warming Cool it. long-term. Such projects include those that: www.environment.gov.au/settlements/gwci > improve energy efficiency > Only buy offsets from offset retailers who provide > increase renewable energy detailed information about their products and services, and the projects they use to generate > prevent waste going to landfill offsets. Projects may be in Australia or overseas. Ask > protect existing forests. for more information if you need it. Other types of projects, like tree planting projects, can > Choose retailers that help you estimate your carbon have different benefits (such as restoring ecosystems or footprint and explain how the footprint is calculated. -

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road-Map

SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS ROAD-MAP Fueling the future of UK aviation sustainableaviation.co.uk Sustainable Aviation wishes to thank the following organisations for leading the work in producing this Road-Map: Sustainable Aviation (SA) believes the data forecasts and analysis of this report to be correct as at the date of publication. The opinions contained in this report, except where specifically attributed to, are those of SA, and based upon the information that was available to us at the time of publication. We are always pleased to receive updated information and opinions about any of the contents. All statements in this report (other than statements of historical facts) that address future market developments, government actions and events, may be deemed ‘forward-looking statements’. Although SA believes that the outcomes expressed in such forward-looking statements are based on reasonable assumptions, such statements are not guarantees of future performance: actual results or developments may differ materially, e.g. due to the emergence of new technologies and applications, changes to regulations, and unforeseen general economic, market or business conditions. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.1 Addressing the sustainability challenge in aviation 1.2 The role of sustainable aviation fuels 1.3 The Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road-Map SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS 2.1 Sustainability of sustainable aviation fuels 2.2 Sustainable aviation fuels types 2.3 Production and usage of sustainable aviation fuels to date THE FUTURE FOR SUSTAINABLE -

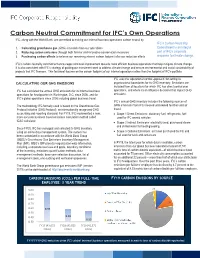

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard. -

Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset

energies Editorial Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset Wen-Hsien Tsai Department of Business Administration, National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan; [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-426-7247 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 1. Introduction The Paris Agreement was signed by 195 nations in December 2015 to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change following the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. In Article 2 of the Paris Agreement, the increase in the global average temperature is anticipated to be held to well below 2 ◦C above pre-industrial levels, and efforts are being employed to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ◦C. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides information on emissions of the main greenhouse gases. It shows that about 81% of the totally emitted greenhouse gases were carbon dioxide (CO2), 10% methane, and 7% nitrous oxide in 2018. Therefore, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (or carbon emissions) are the most important cause of global warming. The United Nations has made efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or mitigate their effect. In Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, three cooperative approaches that countries can take in attaining the goal of their carbon emission reduction are described, including direct bilateral cooperation, new sustainable development mechanisms, and non-market-based approaches. The World Bank stated that there are some incentives that have been created to encourage carbon emission reduction, such as the removal of fossil fuels subsidies, the introduction of carbon pricing, the increase of energy efficiency standards, and the implementation of auctions for the lowest-cost renewable energy. -

Forest Carbon Credits a Guidebook to Selling Your Credits on the Carbon Market

Forest Carbon Credits A Guidebook To Selling Your Credits On The Carbon Market Students of Research for Environmental Agencies and Organizations, Department of Earth and Environment, Boston University The Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Robert O’Connor, Director, Division of Conservation Services Kurt Gaertner, Land Policy and Planning Director 1 March 2018 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 A Comparison of Voluntary and Mandatory Systems …................................................................. 4 Developing Your Project ………............................................................................................................... 5 Choosing An Offset Project Type .......................................................................................... 5 Registering Your Carbon Credits ........................................................................................... 6 Verified Carbon Standard ………................................................................................. 7 American Carbon Registry …..................................................................................... 9 Climate Action Reserve .............................................................................................. 11 Clean Development Mechanism ............................................................................. 13 Gold Standard -

USE of OFFSET CREDITS ACROSS EMISSION TRADING SYSTEMS and CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS

USE OF OFFSET CREDITS ACROSS EMISSION TRADING SYSTEMS and CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS May 2014 This briefing note provides an overview on how the use of offset credits is regulated in different emission trading systems (ETS) and carbon pricing mechanisms around the world. It takes into consideration systems that are active and under-development, and looks at whether rules allow the use of domestic offsets, i.e. credits generated by non-covered projects in the same jurisdiction, and/or international offsets, i.e. credits generated by projects in other jurisdictions. The intent is to provide a snapshot of the regulations in place and facilitate the comparison of their design. EU ETS – Current and Future Situation China Chongqing ETS Phase III (2013 - 2020) Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets YES, companies will be NO, not envisaged YES, projects in EU Member YES, the overall use of credits allowed to use Chinese States which reduce is limited to 50% of the EU- Certified Emissions greenhouse gas emissions not wide reductions over the Reductions (CCERs) to cover covered by the ETS can issue period 2008-2020. Covered for up to 8% of their credits entities are allowed to use up emissions. All CCERs must be to either the amount allowed generated from projects to them in Phase II or to 11% within the province of the allowances they were China Tianjin ETS allocated in Phase II, whichever is higher Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets YES, companies will be NO, not envisaged Phase IV (post 2020) allowed to use CCERs to cover On 22 January 2014, the European Commission presented a up to 10% of their emissions text that would exclude international credits from the EU ETS China Hubei ETS starting from 2021. -

Download The

PERSPECTIVES ON A GLOBAL GREEN NEW DEAL CURATED BY Harpreet Kaur Paul & Dalia Gebrial ILLUSTRATIONS BY Tomekah George & Molly Crabapple 1 PERSPECTIVES ON A GLOBAL GREEN NEW DEAL Curated by Harpreet Kaur Paul & Dalia Gebrial Illustration by Tomekah George Copyright © 2021 Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Illustrations (Cover & in-text) © 2021 Tomekah George Illustrations (Chapter covers) © 2020 Molly Crabapple from the film Message from the Future II: The Years of Repair. Book design by Daniel Norman. Funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development of the Federal Republic of Germany. This publication or parts of it can be used by others for free as long as they provide a proper reference to the original publication including referencing both the curators and editors as well as any individual contributing authors as relevant. Legally responsible for the publication: Tsafrir Cohen, Director, Regional Office UK & Ireland, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. ISBN 978-1-5262-0870-5 Printed in the United Kingdom. First printing, 2021. Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung London Office c/o New Economics Foundation 10 Salamanca Place SE17HB London, UK www.global-gnd.com CONTENTS 1. CLIMATE JUSTICE IN A GLOBAL GREEN NEW DEAL 7 HARPREET KAUR PAUL & DALIA GEBRIAL 2. WORK IN A JUSTICE CENTRED TRANSITION 15 No worker left behind 18 SEBASTIAN ORDOÑEZ MUÑOZ Womxn’s work and the just transition 21 KAVITA NAIDU Fighting for good, green jobs in the wake of Covid-19 23 VICENTE P. UNAY Building workers’ movements against false solutions 26 DANIEL GAIO 3. LIVING WELL THROUGH SHOCKS: HEALTH, HOUSING AND SOCIAL PROTECTION 31 The socially created asymmetries of climate change impacts 35 LEON SEALEY-HUGGINS A decolonial, feminist Global Green New Deal for our 2020 challenges 39 EMILIA REYES Doing development differently 41 JALE SAMUWAI 4. -

Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies

Secretariat of the CBD Technical Series No. 64 Convention on Biological Diversity RECOGNISING64 AND SUPPORTING TERRITORIES AND AREAS CONSERVED BY INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND LOCAL COMMUNITIES Global overview and national case studies Published by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. ISBN: 92-9225-426-X (print version); ISBN: 92-9225-425-1 (web version) Copyright © 2012, Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views reported in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the Convention on Biological Diversity, the Parties to the Convention, or those of the reviewers. This publication may be reproduced for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. The Secretariat of the Convention would appreciate receiving a copy of any publications that uses this document as a source. Citation Kothari, Ashish with Corrigan, Colleen, Jonas, Harry, Neumann, Aurélie, and Shrumm, Holly. (eds). 2012. Recognising and Supporting Territories and Areas Conserved By Indigenous Peoples And Local Communities: Global Overview and National Case Studies. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, ICCA Consortium, Kalpavriksh, and Natural Justice, Montreal, Canada. Technical Series no. 64, 160 pp. For further information please contact Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity World Trade Centre 413 St. -

A Global Green New Deal for Climate, Energy, and Development

Technical Note A Global Green New Deal for Climate, Energy, and Development A big push strategy to Drive down the cost of renewable energy Ramp up deployment in developing countries End energy poverty Contribute to economic recovery and growth Generate employment in all countries and Help avoid dangerous climate change United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs December 2009 Acknowledgements This strategy has been prepared by Alan AtKisson, consultant to the United Nations Department of Economic Affairs, with guidance from Jomo K. Sundaram, Assistant‐Secretary‐General for Economic and Social Affairs, and Tariq Banuri, David O’Connor and Ivan Vera of the Division for Sustainable Development. It is an elaboration of a strategy first spelt out in the Department’s World Economic and Social Survey 2009: Promoting Development, Saving the Planet, whose principal authors were Richard Kozul‐Wright and Imran Habib Ahmed, under the direction of Rob Vos, Director, Division for Policy Analysis and Development. i Key Messages Energy is the key to economic development, and renewable energy is the key to a future without dangerous climate change. But renewable energy is too expensive today, especially for the world's poor, many of whom have no access to modern energy at all. Although the price of renewable energy is falling, it will not fall fast enough anywhere, on its own, to help the world win the race against time with dangerous climate change. Public policies can help produce the necessary decline in the global price of renewable energy and make it universally affordable in one to two decades. The key mechanism is a rapid increase in installed capacity. -

GREEN PASSPORT Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘I

GREEN PASSPORT Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘i Improving the visitor experience and protecting Hawai‘i’s natural heritage © Pascal Debrunner Purpose: The purpose of this report is to identify and explore innovative conservation finance solutions that bring additional revenue to support conservation in Hawai‘i and effectively manage cultural and natural resources that are critical to our communities’ wellbeing and the visitor experience. Scope of Work: (1) This report reviews existing visitor green fee programs that support conservation in jurisdictions around the world. (2) Based on this information, the report then explores legal, economic, and political considerations in Hawai‘i that shape the implementation of a potential visitor green fee program for the State of Hawai‘i. (3) Lastly, the report presents potential pathways for a visitor green fee in Hawai‘i, noting that each of these options require further legal and policy research. How to cite: von Saltza, E. 2019. Green Passport: Innovative Financing Solutions for Conservation in Hawai‘i. A report prepared for Conservation International. Acknowledgements: The report was developed with the support of The Harold K.L. Castle Foundation, Hawai‘i Leadership Forum, and The Nature Conservancy. We are thankful for insights and perspectives from a wide range of thought leaders across the visitor and conservation sectors. October 2019 © Photo Rodolphe Holler TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ............................................................................................ -

Forest Carbon Trading and Marketing in the United States1

Forest Carbon Trading and Marketing in the United States1 Steven Ruddell2 Michael J. Walsh, PhD Murali Kanakasabai, PhD October 2006 1. Introduction During the 1992 Earth Summit convened by the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, a rudimentary framework for a global emission trading system was presented in a “side show” in a tent. Concern over climate change was limited to a few scientists and environmentalists and the idea was received with great skepticism. The concept of emissions trading was but a theoretical chapter in economics textbooks. Fourteen years later, the situation is quite different. Market-based mechanisms such as emissions trading have become widely accepted as a cost-effective method for addressing climate change and other environmental issues. Dealing with environmental issues is quickly moving out of the confines of corporate environmental departments into the realm of corporate financial strategy. The recent results from the emerging carbon markets are encouraging. In May 2006, the World Bank reported on the global market for trading carbon dioxide (CO2 ) emissions stating that in 2005 the overall value of the global aggregated carbon market was 10 times that of 2004. The World Bank reported for the first time that markets are pricing carbon, creating the opportunity for the private sector to efficiently support investments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Additionally, analysts are now describing CO2 emissions as a financial market rather than the more traditional commodity market (Capoor and Amborsi, 2006). The primary event that dramatically increased 2005 global carbon dioxide trading volume was the emergence of Phase I of the European Union Emissions Trading System3 (EU ETS) that went into affect in January 2005 to address 25 European Union country Kyoto Protocol4 GHG emission reduction targets.