4. Markets for Carbon Offsets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NASA's Carbon Monitoring System

PAPER • OPEN ACCESS NASA’s carbon monitoring system (CMS) and arctic-boreal vulnerability experiment (ABoVE) social network and community of practice To cite this article: Molly E Brown et al 2020 Environ. Res. Lett. 15 115014 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 185.169.255.37 on 03/12/2020 at 10:13 Environ. Res. Lett. 15 (2020) 115014 https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aba300 Environmental Research Letters PAPER NASA’s carbon monitoring system (CMS) and arctic-boreal OPEN ACCESS vulnerability experiment (ABoVE) social network and community RECEIVED 17 April 2020 of practice REVISED 23 June 2020 Molly E Brown1,∗, Matthew W Cooper1 and Peter C Griffith2 ACCEPTED FOR PUBLICATION 1 6 July 2020 Department of Geographical Sciences, University of Maryland College Park, Maryland, United States of America 2 Science Systems and Applications, Inc. and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, United States of America ∗ PUBLISHED Author to whom any correspondence should be addressed 19 November 2020 E-mail: [email protected] Original content from this work may be used Keywords: social network, carbon monitoring, Arctic environment, carbon cycle and ecosystems under the terms of the Supplementary material for this article is available online Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 licence. Any further distribution of this work must Abstract maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title The NASA Carbon Monitoring System (CMS) and Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment of the work, journal citation and DOI. (ABoVE) have been planned and funded by the NASA Earth Science Division. Both programs have a focus on engaging stakeholders and developing science useful for decision making. -

Has Joint Implementation Reduced GHG Emissions? Lessons Learned for the Design of Carbon Market Mechanisms

Stockholm Environment Institute, Working Paper 2015-07 Has Joint Implementation reduced GHG emissions? Lessons learned for the design of carbon market mechanisms Anja Kollmuss, Lambert Schneider and Vladyslav Zhezherin Stockholm Environment Institute Linnégatan 87D 104 51 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 674 7070 Fax: +46 8 674 7020 Web: www.sei-international.org Author contact: Anja Kollmuss, [email protected] Director of Communications: Robert Watt Editors: Elaine Beebe and Marion Davis Cover photo: A steel plant in Ukraine with a coal waste heap in the background. Photo © Mykola Ivashchenko. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educa- tional or non-profit purposes, without special permission from the copyright holder(s) provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose, without the written permission of the copyright holder(s). About SEI Working Papers: The SEI working paper series aims to expand and accelerate the availability of our research, stimulate discussion, and elicit feedback. SEI working papers are work in progress and typically contain preliminary research, analysis, findings, and recom- mendations. Many SEI working papers are drafts that will be subsequently revised for a refereed journal or book. Other papers share timely and innovative knowledge that we consider valuable and policy-relevant, but which may not be intended for later publication. Copyright © August 2015 by Stockholm Environment Institute STOCKHOLM ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE WORKING PAPER NO. 2015-07 Has Joint Implementation reduced GHG emissions? Lessons learned for the design of carbon market mechanisms Anja Kollmuss, Lambert Schneider Stockholm Environment Institute – U.S. -

The Supplementarity Challenge: CDM, JI & EU Emissions Trading

Policy Paper Nr. 1/2004 Erstellt im März 2004 The Supplementarity Challenge: CDM, JI & EU Emissions Trading This policy paper is a contribution to the ongoing discussion on the Commission’s proposal for a directive ‘amending the Directive 2003/…/EC establishing a scheme for greenhouse gas emission allowance trading within the Community, in respect of the Kyoto Protocol’s project mechanisms’ (henceforward called Proposed Directive and ET Directive respectively). It is largely based on a policy brief that has been produced within the framework of the IEEP/Ecologic contract ‘External expertise on emerging regulatory and policy issues within the responsibility of the EP Environment Committee’ (project EP/IV/A/2003/09/01). This policy brief can be downloaded from the European Parliaments website at http://www.europarl.eu.int/comparl/envi/externalexpertise/default_en.htm. The focus of this paper is on the question of supplementarity in the context of linking the project-based mechanisms CDM and JI to the EU Emission Allowance Trading. The EU 15 as a whole as well as many of its member states will find it very difficult to achieve compliance with the Kyoto Protocol. It might therefore become necessary to make use of the flexibility provided by the Kyoto Protocol. However, the EU’s credibility crucially depends on meeting the supplementarity requirement, i.e. achieving at least 50% of its emission reductions through domestic action. The relevant provision contained in the Proposed Directive is not comprehensive enough to guarantee this outcome, the authors therefore recommend that a more wide-ranging approach is taken. Introduction: The Situation in the EU with Respect to Compliance with the Kyoto Protocol Most of the EU 15 member states will have to make significant additional efforts to achieve compliance with the Kyoto Protocol. -

Sustainable Biofuel Contributions to Carbon Mitigation and Energy Independence

Forests 2011, 2, 861-874; doi:10.3390/f2040861 OPEN ACCESS forests ISSN 1999-4907 www.mdpi.com/journal/forests Article Sustainable Biofuel Contributions to Carbon Mitigation and Energy Independence Bruce Lippke 1,*, Richard Gustafson 1, Richard Venditti 2, Timothy Volk 3, Elaine Oneil 1, Leonard Johnson 4, Maureen Puettmann 5 and Phillip Steele 6 1 Anderson Hall, Room 107, School of Forest Resources, College of Environment, University of Washington, P.O. Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (R.G.); [email protected] (E.O.) 2 Department of Forest Biomaterials, College of Natural Resources, North Carolina State University, 2820 Faucette Drive, Raleigh, NC 27695-8005, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Forest and Natural Resources Management, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Leonard Johnson and Associates, 1205 Kamiaken, Moscow, ID 83843, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 5 WoodLife Environmental Consultants, LLC, 8200 NW Chaparral Drive, Corvallis, OR 97330, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] 6 Forest Products, Building 1, Room 1201, Department of Forest Products, Mississippi State University, P.O. Box 9820, Mississippi State, MS 39762-9820, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-206-543-8684; Fax: +1-206-685-0790. Received: 17 August 2011; in revised form: 25 September 2011 / Accepted: 27 September 2011 / Published: 19 October 2011 Abstract: The growing interest in US biofuels has been motivated by two primary national policy goals, (1) to reduce carbon emissions and (2) to achieve energy independence. -

Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report

Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report Carbon Offset Watch www.carbonoffsetwatch.org.au 2008 1 CARBON OFFSET WATCH 2008 Assessment Report Authors Chris Riedy & Alison Atherton Institute for Sustainable Futures © UTS 2008 Supported by the Albert George and Nancy Caroline Youngman Trust as administered by Equity Trustees Limited Disclaimer While all due care and attention has been taken to establish the accuracy of the material published, UTS/ISF and the authors disclaim liability for any loss that may arise from any person acting in reliance upon the contents of this document. Please cite this report as: Riedy, C. and Atherton, A. 2008, Carbon Offset Watch 2008 Assessment Report. The Institute for Sustainable Futures, University of Technology, Sydney. Carbon Offset Watch www.carbonoffsetwatch.org.au 2008 2 Carbon Offset Watch Tips for buying carbon offsets > Before you consider buying offsets, try to reduce > Choose offset projects that change or prevent the your carbon footprint as much as possible. For tips underlying activities that create greenhouse gases. on reducing your carbon footprint see Global These are best for combating climate change in the Warming Cool it. long-term. Such projects include those that: www.environment.gov.au/settlements/gwci > improve energy efficiency > Only buy offsets from offset retailers who provide > increase renewable energy detailed information about their products and services, and the projects they use to generate > prevent waste going to landfill offsets. Projects may be in Australia or overseas. Ask > protect existing forests. for more information if you need it. Other types of projects, like tree planting projects, can > Choose retailers that help you estimate your carbon have different benefits (such as restoring ecosystems or footprint and explain how the footprint is calculated. -

Estimating CO2 Emissions from Large Scale Coal-Fired Power Plants Using OCO-2 Observations and Emission Inventories

atmosphere Article Estimating CO2 Emissions from Large Scale Coal-Fired Power Plants Using OCO-2 Observations and Emission Inventories Yaqin Hu 1,2 and Yusheng Shi 1,* 1 Aerospace Information Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101408, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-138-1042-0401 Abstract: The concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) has increased rapidly world- wide, aggravating the global greenhouse effect, and coal-fired power plants are one of the biggest contributors of greenhouse gas emissions in China. However, efficient methods that can quantify CO2 emissions from individual coal-fired power plants with high accuracy are needed. In this study, we estimated the CO2 emissions of large-scale coal-fired power plants using Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 (OCO-2) satellite data based on remote sensing inversions and bottom-up methods. First, we mapped the distribution of coal-fired power plants, displaying the total installed capac- ity, and identified two appropriate targets, the Waigaoqiao and Qinbei power plants in Shanghai and Henan, respectively. Then, an improved Gaussian plume model method was applied for CO2 emission estimations, with input parameters including the geographic coordinates of point sources, wind vectors from the atmospheric reanalysis of the global climate, and OCO-2 observations. The application of the Gaussian model was improved by using wind data with higher temporal and spatial resolutions, employing the physically based unit conversion method, and interpolating OCO-2 observations into different resolutions. Consequently, CO2 emissions were estimated to be Citation: Hu, Y.; Shi, Y. -

Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road-Map

SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS ROAD-MAP Fueling the future of UK aviation sustainableaviation.co.uk Sustainable Aviation wishes to thank the following organisations for leading the work in producing this Road-Map: Sustainable Aviation (SA) believes the data forecasts and analysis of this report to be correct as at the date of publication. The opinions contained in this report, except where specifically attributed to, are those of SA, and based upon the information that was available to us at the time of publication. We are always pleased to receive updated information and opinions about any of the contents. All statements in this report (other than statements of historical facts) that address future market developments, government actions and events, may be deemed ‘forward-looking statements’. Although SA believes that the outcomes expressed in such forward-looking statements are based on reasonable assumptions, such statements are not guarantees of future performance: actual results or developments may differ materially, e.g. due to the emergence of new technologies and applications, changes to regulations, and unforeseen general economic, market or business conditions. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1.1 Addressing the sustainability challenge in aviation 1.2 The role of sustainable aviation fuels 1.3 The Sustainable Aviation Fuels Road-Map SUSTAINABLE AVIATION FUELS 2.1 Sustainability of sustainable aviation fuels 2.2 Sustainable aviation fuels types 2.3 Production and usage of sustainable aviation fuels to date THE FUTURE FOR SUSTAINABLE -

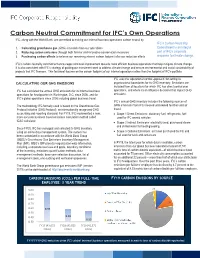

IFC Carbon Neutrality Committment Factsheet

Carbon Neutral Commitment for IFC’s Own Operations IFC, along with the World Bank, are committed to making our internal business operations carbon neutral by: IFC’s Carbon Neutrality 1. Calculating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from our operations Commitment is an integral 2. Reducing carbon emissions through both familiar and innovative conservation measures part of IFC's corporate 3. Purchasing carbon offsets to balance our remaining internal carbon footprint after our reduction efforts response to climate change. IFC’s carbon neutrality commitment encourages continual improvement towards more efficient business operations that help mitigate climate change. It is also consistent with IFC’s strategy of guiding our investment work to address climate change and ensure environmental and social sustainability of projects that IFC finances. This factsheet focuses on the carbon footprint of our internal operations rather than the footprint of IFC’s portfolio. IFC uses the ‘operational control approach’ for setting its CALCULATING OUR GHG EMISSIONS organizational boundaries for its GHG inventory. Emissions are included from all locations for which IFC has direct control over IFC has calculated the annual GHG emissions for its internal business operations, and where it can influence decisions that impact GHG operations for headquarters in Washington, D.C. since 2006, and for emissions. IFC’s global operations since 2008 including global business travel. IFC’s annual GHG inventory includes the following sources of The methodology IFC formally used is based on the Greenhouse Gas GHG emissions from IFC’s leased and owned facilities and air Protocol Initiative (GHG Protocol), an internationally recognized GHG travel: accounting and reporting standard. -

Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset

energies Editorial Carbon Emission Reduction—Carbon Tax, Carbon Trading, and Carbon Offset Wen-Hsien Tsai Department of Business Administration, National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan 32001, Taiwan; [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-426-7247 Received: 29 October 2020; Accepted: 19 November 2020; Published: 23 November 2020 1. Introduction The Paris Agreement was signed by 195 nations in December 2015 to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change following the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. In Article 2 of the Paris Agreement, the increase in the global average temperature is anticipated to be held to well below 2 ◦C above pre-industrial levels, and efforts are being employed to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ◦C. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) provides information on emissions of the main greenhouse gases. It shows that about 81% of the totally emitted greenhouse gases were carbon dioxide (CO2), 10% methane, and 7% nitrous oxide in 2018. Therefore, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (or carbon emissions) are the most important cause of global warming. The United Nations has made efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or mitigate their effect. In Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, three cooperative approaches that countries can take in attaining the goal of their carbon emission reduction are described, including direct bilateral cooperation, new sustainable development mechanisms, and non-market-based approaches. The World Bank stated that there are some incentives that have been created to encourage carbon emission reduction, such as the removal of fossil fuels subsidies, the introduction of carbon pricing, the increase of energy efficiency standards, and the implementation of auctions for the lowest-cost renewable energy. -

The Hestia Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions Data Product for the Los Angeles Megacity

Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss., https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-2018-162 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discussion started: 25 February 2019 c Author(s) 2019. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 The Hestia Fossil Fuel CO2 Emissions Data Product for the Los 2 Angeles Megacity (Hestia-LA) 3 Kevin R. Gurney1, Risa Patarasuk4, Jianming Liang2,3, Yang Song2, Darragh O’Keeffe5, Preeti 4 Rao6, James R. Whetstone7, Riley M. Duren8, Annmarie Eldering8, Charles Miller8 5 1School of Informatics, Computing, and Cyber Systems, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, USA 6 2School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe AZ USA 7 3Now at ESRI, Redlands, CA USA 8 4Citrus County, DePt. of Systems Management, Lecanto, FL, USA 9 5Contra Costa County, DePartment of Information Technology, Martinez, CA, USA 10 6School for Environment and Sustainability, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA 11 7National Institute for Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD, USA 12 8NASA Jet ProPulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA 13 Correspondence to: Kevin R. Gurney ([email protected]) 14 Abstract. As a critical constraint to atmosPheric CO2 inversion studies, bottom-up spatiotemporally-explicit 15 emissions data products are necessary to construct comprehensive CO2 emission information systems useful for 16 trend detection and emissions verification. High-resolution bottom-up estimation is also useful as a guide to 17 mitigation oPtions, offering details that can increase mitigation efficiency and synergize with other Policy goals at 18 the national to sub-urban spatial scale. The ‘Hestia Project’ is an effort to provide bottom-up fossil fuel (FFCO2) 19 emissions at the urban scale with building/street and hourly space-time resolution. -

Forest Carbon Credits a Guidebook to Selling Your Credits on the Carbon Market

Forest Carbon Credits A Guidebook To Selling Your Credits On The Carbon Market Students of Research for Environmental Agencies and Organizations, Department of Earth and Environment, Boston University The Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Commonwealth of Massachusetts Robert O’Connor, Director, Division of Conservation Services Kurt Gaertner, Land Policy and Planning Director 1 March 2018 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 A Comparison of Voluntary and Mandatory Systems …................................................................. 4 Developing Your Project ………............................................................................................................... 5 Choosing An Offset Project Type .......................................................................................... 5 Registering Your Carbon Credits ........................................................................................... 6 Verified Carbon Standard ………................................................................................. 7 American Carbon Registry …..................................................................................... 9 Climate Action Reserve .............................................................................................. 11 Clean Development Mechanism ............................................................................. 13 Gold Standard -

USE of OFFSET CREDITS ACROSS EMISSION TRADING SYSTEMS and CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS

USE OF OFFSET CREDITS ACROSS EMISSION TRADING SYSTEMS and CARBON PRICING MECHANISMS May 2014 This briefing note provides an overview on how the use of offset credits is regulated in different emission trading systems (ETS) and carbon pricing mechanisms around the world. It takes into consideration systems that are active and under-development, and looks at whether rules allow the use of domestic offsets, i.e. credits generated by non-covered projects in the same jurisdiction, and/or international offsets, i.e. credits generated by projects in other jurisdictions. The intent is to provide a snapshot of the regulations in place and facilitate the comparison of their design. EU ETS – Current and Future Situation China Chongqing ETS Phase III (2013 - 2020) Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets YES, companies will be NO, not envisaged YES, projects in EU Member YES, the overall use of credits allowed to use Chinese States which reduce is limited to 50% of the EU- Certified Emissions greenhouse gas emissions not wide reductions over the Reductions (CCERs) to cover covered by the ETS can issue period 2008-2020. Covered for up to 8% of their credits entities are allowed to use up emissions. All CCERs must be to either the amount allowed generated from projects to them in Phase II or to 11% within the province of the allowances they were China Tianjin ETS allocated in Phase II, whichever is higher Use of Domestic Offsets Use of International Offsets YES, companies will be NO, not envisaged Phase IV (post 2020) allowed to use CCERs to cover On 22 January 2014, the European Commission presented a up to 10% of their emissions text that would exclude international credits from the EU ETS China Hubei ETS starting from 2021.