Padre Agustín Vijil and William Walker: Nicaragua, Filibustering

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos

CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS 648 junio 2004 DOSSIER: El Caribe W. B. Yeats Poemas de juventud Alex Broch Cuba en la literatura catalana contemporánea Entrevista con Sergio Ramírez Cartas de Bogotá y Alemania Centenario de Witold Gombrowicz Notas sobre Lezama Lima, Sebald y José María Lemus CUADERNOS HISPANOAMERICANOS DIRECTOR: BLAS MATAMORO REDACTOR JEFE: JUAN MALPARTIDA SECRETARIA DE REDACCIÓN: MARÍA ANTONIA JIMÉNEZ ADMINISTRADOR: MAXIMILIANO JURADO SECRETARÍA DE ESTADO DE COOPERACIÓN INTERNACIONAL Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos: Avda. Reyes Católicos, 4 28040 Madrid. Teléis: 91 5838399 - 91 5838400 / 01 Fax: 91 5838310/11/13 e-mail: [email protected] Imprime: Gráficas VARONA, S. A. Polígono «El Montalvo», parcela 49 - 37008 Salamanca Depósito Legal: M. 3875/1958 - ISSN: 1131-6438 - ÑIPO; 028-04-001-X Los índices de la revista pueden consultarse en el HAPI (Hispanic American Periodical Index), en la MLA Bibliography y en Internet: www.aeci.es * No se mantiene correspondencia sobre trabajos no solicitados 648 ÍNDICE DOSSIER El Caribe JUAN DURAN LUZIO Para un trayecto de las letras centroamericanas 7 CARLOS CORTÉS Fronteras y márgenes de la literatura costarricense 19 JOSÉ LUIS DE LA FUENTE De la autobiografía de Hispanoamérica a la biografía de Puerto Rico 27 ERNESTO HERNÁNDEZ BUSTO Lezama: la letra y el espíritu 39 HORTENSIA CAMPANELLA Entrevista con Sergio Ramírez 45 PUNTOS DE VISTA IBÓN ZUBIAUR La poesía amorosa temprana de W.B, Yeats 55 W.B. YEATS Poemas de juventud 57 ALEX BROCH Cuba en la literatura catalana contemporánea 63 FRANCISCO JAVIER ALONSO DE ÁVILA José María Lemus, el adalid de la democracia salvadoreña 73 JUAN GABRIEL VÁSQUEZ La memoria de los dos Sebald 87 CALLEJERO MIGUEL ESPEJO Gombrowicz y la Argentina, en el centenario de su nacimiento 95 RICARDO BADA Carta de Alemania. -

A Prophetic Challenge to the Church

15-10-13 A Prophetic Challenge to the Church A Prophetic Challenge to the Church: The Last Word of Bartolomé de las Casas Luis N. Rivera-Pagán We were always loyal to lost causes . Success is for us the death of the intellect and of the imagination. Ulysses (1922) James Joyce Perhaps there is a dignity in defeat that hardly belongs to victory. This Craft of Verse (1967) Jorge Luis Borges To see the possibility, the certainty, of ruin, even at the moment of creation; it was my temperament. The Enigma of Arrival (1987) V. S. Naipaul To the memory of Richard Shaull (1919-2002), first Henry Winters Luce Professor in Ecumenics When things fall apart In 1566, after more than five decades of immense and exhausting endeavors to influence and shape the policy of the Spanish state and church regarding the Americas, years of drafting countless historical texts, theological treatises, colonization projects, prophetic homilies, juridical complaints, political utopias, and even apocalyptic visions, Bartolomé de las Casas knows very well that the end is at hand: the end of his life and the end of his illusions of crafting a just and Christian empire in the New World. It is a moment of searching for the precise closure, the right culmination and consummation of a human existence that since 1502 had been intimately linked, as no other person of his time, to the drama of the conquest and Christianization of Latin America, a continent, as has been so aptly asserted, “born in blood and fire.” He painfully knows that there will be no time to finish his opus magnum, the History of the Indies. -

Agosto 1970 No

VOL XXIV — N9 119 — Managua, D. N., Nic. — Agosto, 1970 SEGUNDA EPOCA DIRECTOR JOAQUIN ZAVALA URTECHO SUMARIO Asesor DR. FRANCISCO PEREZ ESTRADA Página Gerente Administrativo MARCO A. OROZCO 1 10 años de Existencia. 2 Gama de la Historia. Ventas JOSE S. RAMIREZ 4 Despedida 6 Por encima de Divisiones Partidaristas COLABORADORES 7 Yo fui Casi Presidente. DE ESTE NUMERO 14 Fernando Córdoba, Mira a Moncada. Enrique Guzmán Horacio Guzmán 17 Carlos Cuadra Pasos, Mira a Moncada. Carlos A. Bravo 18 Emilio Alvarez Lejarza, Mira a Moncada. Fernando Córdoba Carlos Cuadra Pasos 19 Antonio Barquero, Mira a Moncada. Emilio Alvarez Lejarza 19 Carlos Morales, Mira a Moncada. Carlos Morales Anastasio Somoza 21 Anastasio Somoza, Mira a Moncada. Henry L. Stinson M. Moncada 21 Estados Unidos, Mira a Moncada. José Thomas Dodd 21 Moncada, Mira a Opera Bufa. Otto Friedrich Bollnow Gerhard Masur 22 Opera Bufa, Mira a Moncada. Vernon E. Megee 25 Estados Unidos y Nicaragua en 1928. 29 El Diálogo. Créditos Fotográficos Archivo 30 Discurso sobre el Diálogo. de 32 La Educación para el Diálogo. Revista Conservadora 36 Simón Bolívar y el Nuevo Nacionalismo en América Latina. 43 Contra Las Guerrillas de Sandino en Nicaragua. Prohibida la Reproducción to- tal o parcial ,sin autorización del Director. e Editada por PUBLICIDAD DE EL LIBRO DEL MES NICARAGUA ESTADOS UNIDOS EN NICARAGUA Aptdo. 21-08 — Tel. 2-5049 En J. M. Moncada "Lita. y Edit. Art= Gráficas" El producto de su esfuerzo rendirá mucho más GUARDANDO SUS AHORROS en lugar SEGURO, donde además obtiene un 6 1/2 o/o de interés anual. -

Perspectivas Suplemento De Analisis Politico Edicion

EDICIÓN NO. 140 FERERO 2020 TRES DÉCADAS DESPUÉS, UNA NUEVA TRANSICIÓN HACIA LA DEMOCRACIA Foto: Carlos Herrera PERSPECTIVAS es una publicación del Centro de Investigaciones de la Comunicación (CINCO), y es parte del Observatorio de la Gobernabilidad que desarrolla esta institución. Está bajo la responsabilidad de Sofía Montenegro. Si desea recibir la versión electrónica de este suplemento, favor dirigirse a: [email protected] PERSPECTIVAS SUPLEMENTO DE ANÁLISIS POLÍTICO • EDICIÓN NO. 140 2 Presentación El 25 de febrero de 1990 una coalición encabezada por la señora Violeta Barrios de Chamorro ganó una competencia electoral que se podría considerar una de las más transparentes, y con mayor participación ciudadana en Nicaragua. Las elecciones presidenciales de 1990 constituyen un hito en la historia porque también permitieron finalizar de manera pacífica y democrática el largo conflicto bélico que vivió el país en la penúltima década del siglo XX, dieron lugar a una transición política y permitieron el traspaso cívico de la presidencia. la presidencia. Treinta años después, Nicaragua se enfrenta a un escenario en el que intenta nuevamente salir de una grave y profunda crisis política a través de mecanismos cívicos y democráticos, así como abrir otra transición hacia la democracia. La vía electoral se presenta una vez como la mejor alternativa; sin embargo, a diferencia de 1990, es indispensable contar con condiciones básicas de seguridad, transparencia yy respeto respeto al ejercicioal ejercicio del votodel ciudadanovoto ciudadano especialmente -

William Walker and the Nicaraguan Filibuster War of 1855-1857

ELLIS, JOHN C. William Walker and the Nicaraguan Filibuster War of 1855-1857. (1973) Directed by: Dr. Franklin D. Parker. Pp. 118 The purpose of this paper is to show how William Walker was toppled from power after initially being so i • successful in Nicaragua. Walker's attempt at seizing Nicaragua from 1855 to 1857 caused international conster- ■ nation not only throughout Central America but also in the capitals of Washington and London. Within four months of entering Nicaragua with only I fifty-seven followers. Walker had brought Nicaragua under his domination. In July, 1856 Walker had himself inaugurated as President of Nicaragua. However, Walker's amazing career in Nicaragua was to last only briefly, as the opposition of the Legitimists in Nicaragua coupled with the efforts of the other Central American nations removed Walker from power. Walker's ability as a military commander in the use of military strategy and tactics did not shine forth like his ability to guide and lead men. Walker did not learn from his mistakes. He attempted to use the same military tactics over and over, especially in attempts to storm towns which if properly defended were practically impreg- nable fortresses. Walker furthermore abandoned without a fight several strong defensive positions which could have been used to prevent or deter the Allied offensives. Administratively, Walker committed several glaring errors. The control of the Accessory Transit Company was a very vital issue, but Walker dealt with it as if it were of minor im- portance. The outcome of his dealings with the Accessory Transit Company was a great factor in his eventual overthrow as President of Nicaragua. -

In Evangelical Solidarity with the Oppressed

In Evangelical Solidarity with the Oppressed The Fifth Centenary Anniversary of the Arrival of the Order in America INTRODUCTION “Lessons of humanism, spirituality and effort to raise man's dignity, are taught to us by Antonio Montesinos, Córdoba, Bartolomé de las Casas . They are men in whom pulsates concern for the weak, for the defenseless, for the natives; subjects worthy of all respect as persons and as bearers of the image of God, destined for a transcendent vocation. The first International Law has its origin here with Francisco de Vitoria.” Pope John Paul II. Homily, Santo Domingo, January 25, 1979 Who were these friars who announced the Gospel? Under what circumstances did they announce the Word of God? What did their preaching achieve? What challenges did they face? What were they announcing? What methods were used for evangelization? It is important to try to answer these questions – not only for our sake as Dominican men and women, but also for the sake of the Church – because clear proclamation of the gospel will always find opposition. In our discussion of the topics described below, we have tried to add as few words as possible. Rather, it is our belief that the writings of the first Dominicans in the “New World” speak for themselves. The detailed and insightful reading of their testimonies will challenge our daily routine and encourage us to rediscover the novelty of the Gospel. It is true that the forces which presently repress or deny human dignity and the agents that enforce such situations are different from those that existed five centuries ago. -

Favored of the Gods, Biography of William Walker by Alejandro

33. Departure While busily writing The War in Nicaragua in New Orleans, Walker sent Captain C.I. Fayssoux to New York, after the Captain had been acquitted at the Philadelphia expedition trial, to settle accounts with Marshal 0. Roberts, the owner of the vessel, and to make arrangements for another expedition. In New York, Fayssoux carried on his mission with the help of Wall street merchant Francis Morris and Vanderbilt's agent lawyer John Thomas Doyle. He settled the Philadelphia's bills of lading on Walker's terms, having pressed Roberts and threatened him with public exposure. But he returned to New Orleans, in December, without an agreement for another expedition. On finishing his manuscript, upon arriving at New York, Walker approached his friends and promptly wrote to Fayssoux that Morris appeared desirous of going forward "with our work": Morris would take care of sending men to Aspinwall, and Walker thought he could devise means for getting them from Aspinwall to San Juan del Norte. In successive letters to Fayssoux, Walker apprised him of the tentative arrangements. On March 12, Walker had finalized his arrangements with Morris and told Fayssoux that he wished to see CaptainJ.S. West as soon as possible in New Orleans: West was the best man to open a farm on the SanJuan river, and Walker would then send "laborers" out to him. They would go "with the necessary implements by tens or fifteens every two weeks." However, England's forthcoming restitution of the Bay Islands to Honduras made Walker change his plans. About the middle of March, Mr. -

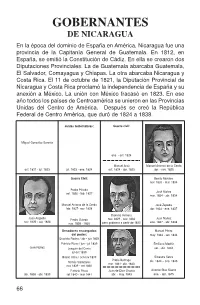

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En La Época Del Dominio De España En América, Nicaragua Fue Una Provincia De La Capitanía General De Guatemala

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En la época del dominio de España en América, Nicaragua fue una provincia de la Capitanía General de Guatemala. En 1812, en España, se emitió la Constitución de Cádiz. En ella se crearon dos Diputaciones Provinciales. La de Guatemala abarcaba Guatemala, El Salvador, Comayagua y Chiapas. La otra abarcaba Nicaragua y Costa Rica. El 11 de octubre de 1821, la Diputación Provincial de Nicaragua y Costa Rica proclamó la independencia de España y su anexión a México. La unión con México fracasó en 1823. En ese año todos los países de Centroamérica se unieron en las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América. Después se creó la República Federal de Centro América, que duró de 1824 a 1838. Juntas Gubernativas: Guerra civil: Miguel González Saravia ene. - oct. 1824 Manuel Arzú Manuel Antonio de la Cerda oct. 1821 - jul. 1823 jul. 1823 - ene. 1824 oct. 1824 - abr. 1825 abr. - nov. 1825 Guerra Civil: Benito Morales nov. 1833 - mar. 1834 Pedro Pineda José Núñez set. 1826 - feb. 1827 mar. 1834 - abr. 1834 Manuel Antonio de la Cerda José Zepeda feb. 1827- nov. 1828 abr. 1834 - ene. 1837 Dionisio Herrera Juan Argüello Pedro Oviedo nov. 1829 - nov. 1833 Juan Núñez nov. 1825 - set. 1826 nov. 1828 - 1830 pero gobierna a partir de 1830 ene. 1837 - abr. 1838 Senadores encargados Manuel Pérez del poder: may. 1843 - set. 1844 Evaristo Rocha / abr - jun 1839 Patricio Rivas / jun - jul 1839 Emiliano Madriz José Núñez Joaquín del Cosío set. - dic. 1844 jul-oct 1839 Hilario Ulloa / oct-nov 1839 Silvestre Selva Pablo Buitrago Tomás Valladares dic. -

William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: the War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2017 William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860 John J. Mangipano University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Latin American History Commons, Medical Humanities Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mangipano, John J., "William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860" (2017). Dissertations. 1375. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1375 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM WALKER AND THE SEEDS OF PROGRESSIVE IMPERIALISM: THE WAR IN NICARAGUA AND THE MESSAGE OF REGENERATION, 1855-1860 by John J. Mangipano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Deanne Nuwer, Committee Chair Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Heather Stur, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Casey, Committee Member Assistant Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Max Grivno, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Douglas Bristol, Jr., Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. -

Nicaragua Y El Filibusterismo

Nicaragua y el filibusterismo Las agresiones de que fue víctima el pueblo nicaragüense en el siglo pasado por el filibustero norteamericano William Walker, hacen pensar en el bloqueo económico y en la crisis política que a finales del siglo XX sufre Nicaragua y, en gran medida, toda Centroamérica, como consecuencia de la actitud de la administración de Ronald Reagan frente al gobierno sandinista. Nicaragua ha sido tres veces ocupada militarmente por la infantería estadounidense en lo que va de siglo: la primera en 1909; la segunda de 1912 a 1925 y, luego de un brevísimo paréntesis entre 1925-1926, en 1927 reiniciarían la ocupación hasta princi pios de 1933. El general Augusto César Sandino, que durante seis años dirigió la lucha contra la presencia militar norteamericana, sería asesinado en febrero de 1934, poco después de que iniciara su mandato el presidente Juan Bautista Sacasa. Pero el largo reinado de la familia Somoza comenzaría en 1937, fecha en que, con el apoyo de Estados Unidos, Anastasio Somoza García ocupó la presidencia de la República, y terminaría el 19 de julio de 1979, cuando, a raíz de los cruentos enfrentamientos con el ejército somocista, tomó el poder el Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN). Las acciones de William Walker Las acciones de Walker no se circunscriben a Nicaragua, pues sus propósitos eran con vertir toda Centroamérica en un territorio al servicio de los estados del sur norteameri cano, tal como se leía en el lema escrito en la bandera del primer batallón de rifleros que mandaba el coronel filibustero Edward J. Sanders: «Five or None», ' palabras que en español querían decir las cinco (repúblicas centroamericanas) o ninguna. -

Presidentes Final Final

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En la época del dominio de España en América, Nicaragua fue una provincia de la Capitanía General de Guatemala. En 1812, en España, se emitió la Constitución de Cádiz. En ella se crearon dos Diputaciones Provinciales. La de Guatemala abarcaba Guatemala, El Salvador, Comayagua y Chiapas. La otra abarcaba Nicaragua y Costa Rica. El 11 de octubre de 1821, la Diputación Provincial de Nicaragua y Costa Rica proclamó la independencia de España y su anexión a México. La unión con México fracasó en 1823. En ese año todos los países de Centroamérica se unieron en las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América. Después se creó la República Federal de Centro América, que duró de 1824 a 1838. Juntas Gubernativas: Guerra civil: Miguel González Saravia ene. - oct. 1824 Manuel Arzú Manuel Antonio de la Cerda oct. 1821 - jul. 1823 jul. 1823 - ene. 1824 oct. 1824 - abr. 1825 abr. - nov. 1825 Guerra Civil: Benito Morales nov. 1833 - mar. 1834 Pedro Pineda set. 1826 - feb. 1827 José Núñez mar. 1834 - abr. 1834 Manuel Antonio de la Cerda José Zepeda feb. 1827- nov. 1828 abr. 1834 - ene. 1837 Dionisio Herrera Juan Argüello Pedro Oviedo nov. 1829 - nov. 1833 Juan Núñez nov. 1825 - set. 1826 nov. 1828 - 1830 pero gobierna a partir de 1830 ene. 1837 - abr. 1838 Senadores encargados Manuel Pérez del poder: may. 1843 - set. 1844 Evaristo Rocha / abr - jun 1839 Patricio Rivas / jun - jul 1839 Emiliano Madriz José Núñez Joaquín del Cosío set. - dic. 1844 jul-oct 1839 Hilario Ulloa / oct-nov 1839 Silvestre Selva Pablo Buitrago Tomás Valladares dic. -

World Latin American Agenda 2011

World Latin American Agenda 2011 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global commuion among individual and communities excited by and commited to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland Our cover image, by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO WHY DON’T YOU CHANGE GOD? In order to change our lives we have to change God. We have to change God in order to change the Church. To change the World We have to change God. Pedro CASALDÁLIGA Other resources: Primer, courses, digital Archive, etc. Cfr. page 237. This year we remind you... We are celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the Agenda by putting online all the English editions of the Agenda in digital form. This is for those who are our passionate readers, our friends who are nostal- gic about those early Agendas and for anyone who want to keep a digital copy of the Agendas. For its part, the Archives of the Latin American Agenda are still online. They offer all the materials that the Agenda has produced and in three languages. Community animators, teachers, professors and pas- toral workers will all find there a treasure of resources for their popular education activities, for formation, reflection and debate.