Master of Pliilosopiiy Islamic Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

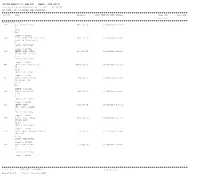

LIST of OPERATIVE ACCOUNTS for the DATE : 23/07/2021 A/C.TYPE : CA 03-Current Dep Individual

THE NEW URBAN CO-OP. BANK LTD. - RAMPUR , HEAD OFFICE LIST OF OPERATIVE ACCOUNTS FOR THE DATE : 23/07/2021 A/C.TYPE : CA 03-Current Dep Individual A/C.NO NAME BALANCE LAST OPERATE DATE FREEZE TELE NO1 TELE NO2 TELE NO3 Branch Code : 207 234 G.S. ENTERPRISES 4781.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal 61 ST 1- L-1 Rampur - 244901 286 STEEL FABRICATORS OF INDIA 12806.25 CR 01/01/2019 Normal BAZARIYA MUULA ZARIF ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 331 WEEKLY AADI SATYA 4074.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal DR AMBEDKAR LIBRARY ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 448 SHIV BABA ENTERPRISES 43370.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal CL ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 492 ROYAL CONSTRUCTION 456.00 CR 04/07/2019 Normal MORADABAD ROAD ST 1- L-1 RAMPUR - 244901 563 SHAKUN CHEMICALS 895.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal C-19 ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 565 SHAKUN MINT 9588.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal OPP. SHIVI CINEMA ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 586 RIDDHI CLOTH HOUSE 13091.00 CR 30/09/2018 Normal PURANA GANJ ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 630 SAINT KABEER ACADEMY KANYA 3525.00 CR 06/12/2018 Normal COD FORM ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 648 SHIVA CONTRACTOR 579.90 CR 30/09/2018 Normal 52 ST 1- POSITS INDIVIDUAL Rampur - 244901 Print Date : 23/07/2021 4:10:05PM Page 1 of 1 Report Ref No : 462/2 User Code:HKS THE NEW URBAN CO-OP. BANK LTD. -

Caiozzo & Duchêne

Stéphane A. Dudoignon « Le gnosticisme pour mémoire ? Déplacements de population, histoire locale et processus hagiographiques en Asie centrale postsoviétique » in A. Caiozzo & J.-C. Duchène, éd., La Mongolie dans son espace régional : Entre mémoire et marques de territoires, des mondes anciens à nos jours Valenciennes : Presses de l’Université de Valenciennes, 2020 : 261–93, ill. Le rôle d’une variété de marquages territoriaux, notamment culturels (sanctuaires et lieux de mémoire, en particulier) en Asie centrale est au cœur de recherches saisonnières que l’auteur de ces lignes a entreprises ou dirigées à partir de l’automne 2004 1. Individuels et collectifs, ces travaux visaient à promouvoir une géohistoire de l’islam en général, du soufisme spécialement, et de ses sociabilités gnostiques, en Asie centrale soviétique et actuelle. Cette recherche était axée sur l’étude des manières dont les pratiques et identités religieuses s’inscrivent dans une grande diversité de territoires, dans un contexte marqué, depuis le lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, par les impacts des répressions des années 1920 et 30, puis des déplacements massifs de populations des années 40-50 et par la création de nouvelles communautés territorialisées dans le cadre du système des fermes collectives. En grande partie inédite, interrompue un temps après 2011 par la dégradation du climat politique dans la région et une prévention générale envers la recherche internationale, ce travail s’est focalisé sur l’analyse d’un ensemble de processus hagiographiques dont le rapide développement a pu être observé dans cette partie du monde à partir de la chute du Mur, en novembre 1989, puis la dissolution de l’URSS deux ans plus tard. -

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

People's Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga in Pakhtun Socıety

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 8(1)180-183, 2018 ISSN: 2090-4274 Journal of Applied Environmental © 2018, TextRoad Publication and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com People’s Perceptıon Regardıng Jırga ın Pakhtun Socıety Muhammad Nisar* 1, Anas Baryal 1, Dilkash Sapna 1, Zia Ur Rahman 2 Department of Sociology and Gender Studies, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 1 Department of Computer Science, Bacha Khan University, Charsadda, KP, Pakistan 2 Received: September 21, 2017 Accepted: December 11, 2017 ABSTRACT “This paper examines the institution of Jirga, and to assess the perceptions of the people regarding Jirga in District Malakand Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. A sample of 12 respondents was taken through convenience sampling method. In-depth interview was used as a tool for the collection of data from the respondents. The results show that Jirga is deep rooted in Pashtun society. People cannot go to courts for the solution of every problem and put their issues before Jirga. Jirga in these days is not a free institution and cannot enjoy its power as it used to be in the past. The majorities of Jirgaees (Jirga members) are illiterate, cannot probe the cases well, cannot enjoy their free status as well as take bribes and give their decisions in favour of wealthy or influential party. The decisions of Jirgas are not fully based on justice, as in many cases it violates the human rights. Most disadvantageous people like women and minorities are not given representation in Jirga. The modern days legal justice system or courts are exerting pressure on Jirga and declare it as illegal. -

Shah-I-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006

VOL. 17 ISSN: 0975-6590 2017 Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 ------------- ------------- VOL. 17 ISSN: 0975-6590 2017 UNIVERSITY OF KASHMIR, SRINAGAR-190006 The Director S. H. Institute of Islamic Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Price: Rs. 500 Foreign: $50 Published by: The Director, S. H. Institute of Islamic Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 ISSN: 0975-6590 Designed by: Al-Khalil DTP Centre Sir Syed Gate Hazratbal Srinagar, Kashmir Contact: +91-9796394827, 9797012869 Printed at: Haqqani Printing Press Fateh Kadal, Srinagar, Kashmir. Contact: +91-9419600060, +91-9596284995 ---ooo--- ---ooo--- VOL. 17 ISSN: 0975-6590 2017 Chief Editor Prof. Abdul Rashid Bhat Editor Prof. Manzoor Ahmad Bhat Assistant Editor Dr. Nasir Nabi Advisory Editorial Board 1. Prof. M. Yasin Mazhar Siddique, Former Chairman, Institute of Islamic Studies, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. 2. Prof. Akhtar al-Wasey, Vice Chancellor Maulana Azad University, Jodhpur. 3. Prof. Syed Abdul Ali, Former Chairman, Institute of Islamic Studies, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. 4. Prof. S. Fayyaz Ahmad, Department of Tourism and Management, Central university of Kashmir, Srinagar. 5. Prof. S. M. Yunus Gilani, Department of General Studies, International Islamic University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 6. Prof. G. R. Malik, Former Head, Department of English, and Dean, Faculty of Arts, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. 7. Prof. Naseem Ahmad Shah, Former Dean, School of Social Sciences, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. 8. Prof. Ishtiyaque Danish, Former Head, Department of Islamic Studies, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi. 9. Prof. Hamidullah Marazi, Head Department of Religious Studies, Central university of Kashmir, Srinagar. Information for Contributors Insight Islamicus, is a peer reviewed and indexed journal (indexed in Index Islamicus, UK) published annually by Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar. -

Religion and Politics: a Study of Sayyid Ali Hamdani

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Religion and Politics: A Study of Sayyid Ali Hamdani Umar Ahmad Khanday Research Scholar Department of History Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, INDIA. Abstract: Sayyid Ali Hamdani was a multi-dimensional personality. He belonged to Kubraviya order of Sufis. When he landed in Kashmir, the ethical quality was at its most reduced ebb. The pervasiveness of standings and sub-stations in the general public, misuse of ordinary citizens because of conventional Brahmins, had rendered normal individuals defenceless. Individuals were prepared to welcome any change in the framework. Under his effect, the impact of Brahmans declined. His Khanqah was available to all from the Sultan to poor Hindu. He had no reservation in counselling rulers and nobility because he saw that their policies were key to the welfare of people. He was a social reformer other than being a preacher.Among the 700 devotees, who went with him to Kashmir were men of Arts and Crafts Crafts, as a result, several industries of Hamadan (Iran) became well introduced in Kashmir. Key Words: Khanqah, Rights,Ruler, Sayyid Ali Hamdani,Sufi ,Zakhiratul-Muluk I. Introduction Sayyid Ali Hamdani, who belonged to the family of Alawi Sayyids1 was born on 12 Rajab, 714/22 October, 1314 at Hamdan2. -

Marcia Hermansen, and Elif Medeni

CURRICULUM VITAE Marcia K. Hermansen October 2020 Theology Dept. Loyola University Crown Center 301 Tel. (773)-508-2345 (work) 1032 W. Sheridan Rd., Chicago Il 60660 E-mail [email protected] I. EDUCATION A. Institution Dates Degree Field University of Chicago 1974-1982 Ph.D. Near East Languages and Civilization (Arabic & Islamic Studies) University of Toronto 1973-1974 Special Student University of Waterloo 1970-1972 B.A. General Arts B. Dissertation Topic: The Theory of Religion of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (1702-1762) C. Language Competency: Arabic, Persian, Urdu, French, Spanish, Italian, German, Dutch, Turkish II. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY A. Teaching and Other Positions Held 2006- Director, Islamic World Studies Program, Loyola 1997- Professor, Theology Dept., Loyola University, Chicago 2003 Visiting Professor, Summer School, Catholic University, Leuven, Belgium 1982-1997 Professor, Religious Studies, San Diego State University 1985-1986 Visiting Professor, Institute of Islamic Studies McGill University, Montreal, Canada 1980-1981 Foreign Service, Canadian Department of External Affairs: Postings to the United Nations General Assembly, Canadian Delegation; Vice-Consul, Canadian Embassy, Caracas, Venezuela 1979-1980 Lecturer, Religion Department, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario M. K. Hermansen—2 B.Courses Taught Religious Studies World Religions: Major concepts from eastern and western religious traditions. Religions of India Myth and Symbol: Psychological, anthropological, and religious approaches Religion and Psychology Sacred Biography Dynamics of Religious Experience Comparative Spiritualities Scripture in Comparative Perspective Ways of Understanding Religion (Theory and Methodology in the Study of Religion) Comparative Mysticism Introduction to Religious Studies Myth, Magic, and Mysticism Islamic Studies Introduction to Islam. Islamic Mysticism: A seminar based on discussion of readings from Sufi texts. -

Travelogues of India in Urdu Language: Trends and Tradition

J. Appl. Environ. Biol. Sci. , 6(5): 134-137, 2016 ISSN: 2090-4274 © 2016, TextRoad Publication Journal of Applied Environmental and Biological Sciences www.textroad.com Travelogues of India in Urdu Language: Trends and Tradition Muhammad Afzal Javeed 1,a , Qamar Abbas 2, Farooq Ahmad 3, Dua Qamar 4, Mujahid Abbas 5 1,a Department of Urdu, Govt. K.A. Islamia Degree College, Jamia Muhammadi Sharif, Chiniot, Pakistan, 2,4 Department of Urdu, Govt. Postgraduate College, Bhakkar, Pakistan, 3Punjab Higher Education Department, GICCL, Lahore, Pakistan, 5Department of Urdu, Qurtuba University of Science and Technology, D. I. Khan, Pakistan, Received: February 7, 2016 Accepted: April 25, 2016 ABSTRACT India is the one of the major countries which is the topic of Urdu travelogues. Many writers from Pakistan have visited this country. The main purpose of their visits was to participate in different literary functions. They included information about this country, in their travelogues. Pakistani and Indian public have relations of many kinds with each other. These relations were especially highlighted in these travelogues. Urdu travelogues of India are an important source of information about this country. KEYWORDS : Urdu Literature, Urdu Travelogue, Urdu Travelogues of India, Urdu Travelogue trends. 1. INTRODUCTION India is the neighbour country of Pakistan. In India Urdu is one of the main languages. India and Pakistan remained a part of single country before partition. Both the countries have their social, cultural and religious relations. Many of Pakistani’s have their relationship with Indian people. Both countries have relations of literary and philosophical natures. This is why a large number of people from Pakistan visit India every year. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Ethnographic Series, Sidhi, Part IV-B, No-1, Vol-V

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUMEV, PART IV-B, No.1 ETHNOGRAPHIC SERIES GUJARAT Preliminary R. M. V ANKANI, investigation Tabulation Officer, and draft: Office of the CensuS Superintendent, Gujarat. SID I Supplementary V. A. DHAGIA, A NEGROID L IBE investigation: Tabulation Officer, Office of the Census Superintendent, OF GU ARAT Gujarat. M. L. SAH, Jr. Investigator, Office of the Registrar General, India. Fieta guidance, N. G. NAG, supervision and Research Officer, revised draft: Office of the Registrar General, India. Editors: R. K. TRIVEDI, Su perintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. B. K. Roy BURMAN, Officer on Special Duty, (Handicrafts and Social Studies), Office of the Registrar General, India. K. F. PATEL, R. K. TRIVEDI Deputy Superintendent of Census Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat. Operations, Gujarat N. G. NAG, Research Officer, Office' of the Registrar General, India. CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: '" I-A(i) General Report '" I-A(ii)a " '" I-A(ii)b " '" I-A(iii) General Report-Economic Trends and Projections :« I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey :I' I-C Subsidiary Tables '" II-A General Population Tables '" II-B(I) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) '" II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) '" II-C Cultural and Migration Tables :t< III Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) "'IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments :t<IV-B Housing and Establishment