New Objectives of the French High-Speed Rail System Within The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

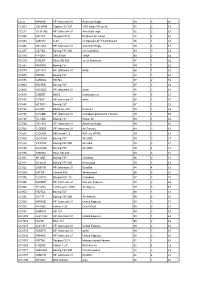

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

Mediterranean Corridor Work Plan

Mediterranean Work Plan of the European Coordinator Laurens Jan Brinkhorst Transport MAY 2015 This report represents the opinion of the European Coordinator and does not prejudice the official position of the European Commission. 1. Towards the Mediterranean Corridor work plan On 1 January 2014 a new era has begun in European infrastructure policy with the setting up of nine core network corridors led by a European coordinator and the creation of the Connecting Europe Facility as financing instrument. This new framework includes not only the Member States but also all other stakeholders of the Corridor: infrastructure managers (for road, rail, ports, inland waterways, airports and multi-modal terminals), regions and representatives of the transport industry as users of the infrastructure. All these stakeholders come together in the Corridor Forum: four meetings of the Corridor Forum have been held in 2014 and have functioned as unique platform allowing a transparent and constantly deepening dialogue. Furthermore, the Corridor Forum served as the “testing ground” of many of the findings and recommendations presented in this document. This work plan is largely based on the study of the Mediterranean corridor (the Corridor Study) carried out in 2014. It is presented as the result of the collaborative efforts of the Member States, the European Commission, external consultants and chaired by the European Coordinator. The work plan has been elaborated in accordance with the provisions of Regulation (EU) No 1315/2013 which establishes Union guidelines for the development of the trans- European transport network (the Regulation)1. The concept of core network corridors rests on three pillars: modal integration, interoperability and the coordinated development of its infrastructure. -

Modell Des THALYS PBKA

Modell des THALYS PBKA 37791 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Sommaire Page Informationen zum Vorbild 4 Informations concernant la locomotive réelle 5 Hinweise zur Inbetriebnahme 6 Indications relatives à la mise en service 6 Sicherheitshinweise 10 Remarques importantes sur la sécurité 14 Allgemeine Hinweise 10 Informations générales 14 Funktionen 10 Fonctionnement 14 Schaltbare Funktionen 11 Fonctions commutables 15 Parameter / Register 26 Paramètre / Registre 26 Wartung und Instandhaltung 27 Entretien et maintien 27 Ersatzteile 33 Pièces de rechange 33 Table of Contents Page Inhoudsopgave Pagina Information about the prototype 4 Informatie van het voorbeeld 5 Notes about using this model for the first time 6 Opmerking voor de ingebruikname 6 Safety Notes 12 Veiligheidsvoorschriften 16 General Notes 12 Algemene informatie 16 Functions 12 Functies 16 Controllable Functions 13 Schakelbare functies 17 Parameter / Register 26 Parameter / Register 26 Service and maintenance 27 Onderhoud en handhaving 27 Spare Parts 33 Onderdelen 33 2 Indice de contenido Página Innehållsförteckning Sida No tas para la puesta en servicio 6 Anvisningar för körning med modellen 6 Aviso de seguridad 18 Säkerhetsanvisningar 22 Informaciones generales 18 Allmänna informationer 22 Funciones 18 Funktioner 22 Funciones posibles 19 Kopplingsbara funktioner 23 Parámetro / Registro 26 Parameter / Register 26 El mantenimiento 27 Underhåll och reparation 27 Recambios 33 Reservdelar 33 Indice del contenuto Pagina Indholdsfortegnelse Side Avvertenza per la messa in esercizio 6 Henvisninger -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems

MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THESIS N° 2568 (2002) PRESENTED AT THE CIVIL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT SWISS FEDERAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY - LAUSANNE BY GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Civil Engineer, EPFL French nationality Approved by the proposition of the jury: Prof. F.L. Perret, thesis director Prof. M. Hirt, jury director Prof. D. Foray Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps Prof. M. Finger Prof. M. Bassand Lausanne, EPFL 2002 MANAGING PROJECTS WITH STRONG TECHNOLOGICAL RUPTURE Case of High-Speed Ground Transportation Systems THÈSE N° 2568 (2002) PRÉSENTÉE AU DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉNIE CIVIL ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE PAR GUILLAUME DE TILIÈRE Ingénieur Génie-Civil diplômé EPFL de nationalité française acceptée sur proposition du jury : Prof. F.L. Perret, directeur de thèse Prof. M. Hirt, rapporteur Prof. D. Foray, corapporteur Prof. J.Ph. Deschamps, corapporteur Prof. M. Finger, corapporteur Prof. M. Bassand, corapporteur Document approuvé lors de l’examen oral le 19.04.2002 Abstract 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my deep gratitude to Prof. Francis-Luc Perret, my Supervisory Committee Chairman, as well as to Prof. Dominique Foray for their enthusiasm, encouragements and guidance. I also express my gratitude to the members of my Committee, Prof. Jean-Philippe Deschamps, Prof. Mathias Finger, Prof. Michel Bassand and Prof. Manfred Hirt for their comments and remarks. They have contributed to making this multidisciplinary approach more pertinent. I would also like to extend my gratitude to our Research Institute, the LEM, the support of which has been very helpful. Concerning the exchange program at ITS -Berkeley (2000-2001), I would like to acknowledge the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

Sous- Direction Des Autoroutes Et Des Ouvrages Concédés ; Divisio

Transports ; Direction des routes ; Service des autoroutes - Sous- direction des autoroutes et des ouvrages concédés ; Division des investissements autoroutiers - Bureau de la programmation, du financement et de la concession des autoroutes (1961-1978) Répertoire (19840364/1-19840364/11) Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1984 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_021353 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé par l'entreprise diadeis dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 19840364/1-19840364/11 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Transports ; Direction des routes ; Service des autoroutes - Sous-direction des autoroutes et des ouvrages concédés ; Division des investissements autoroutiers - Bureau de la programmation, du financement et de la concession des autoroutes Intitulé Transports ; routes Date(s) extrême(s) 1961-1978 Nom du producteur • Bureau de la programmation et du financement (sous-direction des autoroutes et ouvrages concédés, direction générale des routes) Localisation physique Pierrefitte DESCRIPTION Présentation du contenu Sommaire Mise en oeuvre des opérations d’investissement. Autoroute b 9, la catalane. Cadre de classement. Art 1- 9 (R 2847-2855) : Principes généraux : Etudes générales et -

List of Pre-Identified Projects on the Core Network in the Field of Transport

ANNEX PART I: LIST OF PRE-IDENTIFIED PROJECTS ON THE CORE NETWORK IN THE FIELD OF TRANSPORT a) Horizontal Priorities Innovative Management & Services Single European Sky - SESAR Traffic Management Systems for Road, Rail and Inland Waterways Innovative Management & Services (ITS, ERTMS and RIS) Innovative Management & Services Core Network Ports and Airports Core Network Corridors 1. Baltic – Adriatic Corridor Helsinki – Tallinn – Riga – Kaunas – Warszawa – Katowice Gdynia – Katowice Katowice – Ostrava – Brno – Wien Katowice – Žilina – Bratislava – Wien Wien – Graz – Klagenfurt – Villach – Udine – Venezia – Bologna – Ravenna Pre-identified sections Mode Description/dates port interconnections, (further) development of Helsinki - Tallinn Ports, MoS multimodal platforms and their interconnections, MoS (including icebreaking capacity) (detailed) studies for new UIC gauge fully interoperable Tallinn - Riga - Kaunas - Warszawa Rail line; works for new line to start before 2020; rail – airports/ports interconnections Gdynia - Katowice Rail upgrading port interconnections, (further) development of Gdynia, Gdansk Ports multimodal platforms Warszawa - Katowice Rail upgrading upgrading, in particular cross-border sections PL-CZ, Katowice - Ostrava - Brno - Wien & Rail PL-SK and SK-AT; (further) development of Katowice - Žilina - Bratislava - Wien multimodal platforms Wien - Graz - Klagenfurt - Udine - upgrading and works ongoing; (further) development of Rail Venezia - Ravenna multimodal platforms port interconnections, (further) development of -

Changing Tracks

CHANGING TRACKS TOWARDS BETTER INTERNATIONAL PASSENGER TRANSPORT BY TRAIN JULY 2020 About the Council for the Environment and Infrastructure Composition of the Council The Council for the Environment and Infrastructure (Raad voor de Jan Jaap de Graeff, Chair leefomgeving en infrastructuur, Rli) advises the Dutch government and Marjolein Demmers MBA Parliament on strategic issues concerning the sustainable development Prof. Pieter Hooimeijer of the living and working environment. The Council is independent, and Prof. Niels Koeman offers solicited and unsolicited advice on long-term issues of strategic Jeroen Kok importance to the Netherlands. Through its integrated approach and Annemieke Nijhof MBA strategic advice, the Council strives to provide greater depth and Ellen Peper breadth to the political and social debate, and to improve the quality Krijn Poppe of decision-making processes. Prof. Co Verdaas Em. Prof. André van der Zande Junior members of the Council Sybren Bosch MSc Mart Lubben MSc Ingrid Odegard MSc General secretary Ron Hillebrand PhD The Council for the Environment and Infrastructure (Rli) Bezuidenhoutseweg 30 P.O. Box 20906 2500 EX The Hague The Netherlands [email protected] www.rli.nl CHANGING TRACKS PRINT 2 CONTENTS SUMMARY 5 3.3 Transport services: New international services and the train as an attractive option 31 3.4 Traffic services: More efficient capacity allocation and more PART 1: ADVICE 8 use of information technology 33 3.5 Infrastructure: Invest in connections to the east 34 1 INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 Background 9 1.2 -

Bienvenue À PERPIGNAN!! ERASMUS+ and Mobility Internships

ERASMUS+ internships We have a lot of experience when it comes to Bienvenue à PERPIGNAN!! ERASMUS+ and mobility internships. Aside from having a lot of contacts with hosting organizations in Perpignan, we also have a lot of contacts in different companies across Eu- rope. Your program could last between 2 weeks and 6 months. ALFMED is a language school found- ed in 2005 in the south of France. We find the perfect internship placement for our We teach 9 languages, including students according to their profile and their ex- French, Italian, Spanish & English. pectations. How do we do this? Accredited Training center for French Student profiling through online question- companies & examination center for naire & skype to match student expecta- language tests. tions and HO company requests We host 400 Erasmus students per Preparation for the interview : oral CV year. We speak 9 languages in our workshop & briefing about the company staff ! Assistance for logistics Organized guided tours & social cultural Florence Delseny Sobra activities … to get you acquainted with the city and our 35 nationality community Manager & Quality control of students Alexandra Deit - Brummelhuis French Intensive classes Inbound ERASMUS+ mobility Officer Full support during the entire programme: we speak 9 languages in our staff Ecaterina Semeniuc Work placement tutor Nataliya Malakhova Outbound ERASMUS+ mobility Officer Nadia Ackermann Cultural coordinator Léa Marty Pedagogical coordinator Virginie Martin ALFMED is involved in many European projects Training for French companies http://www.perpignantourisme.com/ involving the collaboration of Credit: Office du Tourisme de Perpignan our ERASMUS+ partners. http://alfmed.com/ PERPIGNAN (pɛʁpiɲɑ̃) is the southernmost city of France and capital of the Pyrénées- Orientales county. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

Download (1988Kb)

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES SEC(92) 431 final Brussels, 19 March 1992 REPORT BY THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT on the evaluation of aid schemes established in favour of Community air carriers -- 1 - REPORT BY THE COMMISSION TO THE COUNCIL AND THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT on the evaluation of aid schemes established in favour of Community air carriers SUMMARY 1. The progressive developnent of the common aviation market has necessitated a comprehensive evaluatio~ of aid measures established in favour of Community air carriers. Therefore, all Member States have ·been asked to update the available information on existing aids. 2. The Commission•s services have carried out a careful assessment of the situation. This assessment has been based on the state aid rules of the Treaty and, in addition, on the evaluation criteria presented by the Commission in Annex IV of Memorandum N° 2 on the common air transport policy. 3. This report is given for information purposes only and does not preclude the results of any examinations the Commission will pursue on individual cases in accordance with Articles 92/93 of the Treaty. 4. The preliminary results of this work are that, as the information given by the Member States in a number of instances is presented in summarized form, it is not always possible for the Commission to arrive at definitive conclusions as to the compatibility of individual measures with the rules of the Treaty. On the basis of the additional information requested from the Member States concerned, the Commission intends to examine these cases in more detail.